Writing the Song of Myself

An Interview with Sean Landers

In the beginning was the word and the word got fleshed out. That would be the opening line in Sean Landers’s version of his Bible, were he to write one. It would be a kind of secular new testimony because, for him, language is the medium and the message. When I say, the word gets “fleshed out,” I mean it literally. Both his written paintings and [sic], his quasi-fictional, quasi-factual Bildungsroman, are overflowing with the pleasures and the anxieties of the flesh. He presents himself as two characters, one who is a writing self and the other a fictive self, and together they tell the story of Sean Landers. He says the fictive persona not only makes things more interesting, but it also provides him “with a fig leaf to hide behind.” There are occasions when that cover falls off and he ends up being full-on leafless. His early videos and language paintings are delightfully outrageous acts of exposure. Were he to make one, his philosophical declaration would be Discoperio ergo sum. The translation goes something like, “I uncover and lay bare; therefore I am.”

In understanding the world according to Sean Landers, staying within the territory of fauna and florid is appropriate, not only because he has painted a series of North American mammals with tartan-covered bodies, but because of his fondness for metaphors of growth. In addition to the discretion of his fig leaf, he also explains his passion for writing through nature. “The desire and the need to write have always been central to what I have done,” he says in the following interview. “The way I like to imagine it is, all my work is a tree and writing is the trunk of that tree and the branches are the various series I have made.”

The branches have been richly unpredictable. Landers has particular admiration for Francis Picabia, the polymathic French artist, because “he was not governed by style and he went through so many changes and had so many ways to express himself throughout his long life and I want the same thing.”

Sean Landers, I Was Here, 2018, oil on linen, 77.25 x 59.5 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke Studio. © Sean Landers. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York.

Landers has realized what he wanted. His series have included Art, Life and God, 1990, a collection of texts written by his alter ego, Chris Hamson, the first indication that “intimate personal content is extremely compelling”; a number of giant “Writing Paintings” on unstretched linen, like For the Love of Nothing and I’m a Clown in a World of Chimps, both from 1994; and a suite of oil paintings based on William Hogarth’s A Midnight Modern Conversation, c 1732, a painting that he became fascinated with on a return visit to Yale, his alma mater, 10 years after graduating with his MFA. In 2003 he produced a series of tribute paintings in which he depicted his favourite 20th-century artists as clowns—De Chirico is a Viking, Salvador Dali is a king and Georges Braque an elf—and they are joined in the tributary gallery by a series of grisaille ghosts, including Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Max Beckmann and Martin Kippenberger.

Among the clowns is René Magritte, imagined as a devil, and some of that demonic irreverence has rubbed off on Landers and caused him to make paintings like Plankboy Hurt, 2009, where a wood-grained boy lies folded up in a wintry landscape; and Trial and Error, 2016, where Magritte’s troubling image of a woman’s face morphs into her naked body, and then is taken one step further with the addition of a drooping dark moustache above her sexualized mouth. In 2014 at the Petzel Gallery in New York, he exhibited an ambitious combination of paintings of steel-grey library bookshelves and tartan-skinned animals, including a silver fox, a blue buck, a pink lynx and a whale that measures in at 112 x 336 inches.

In 2018 he scaled down and moved from fauna to flora in a series of aspen trees with messages carved on their bark, and still another series of paintings of wooden roadside signposts with directional pointers that ask, ‘is art a thing itself or a depiction, or can it be both things at once?’ These conjectures and queries are followed by a plank that suggests ‘maybe the painting is just a picture of signs’, an idea that is both a reduction of possible reads and a journey that points you in the direction of a village called Semiotics. Landers admits that his problem stems from “an empty canvas and an unwillingness to repeat the thing that’s popular,” and his response has resulted in a cornucopia of subjects and approaches. “As soon as something becomes popular,” he says, “I develop wanderlust and want to get away.”

Both Things at Once, 2018, oil on linen, 59.5 x 77.25 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke Studio. © Sean Landers. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York.

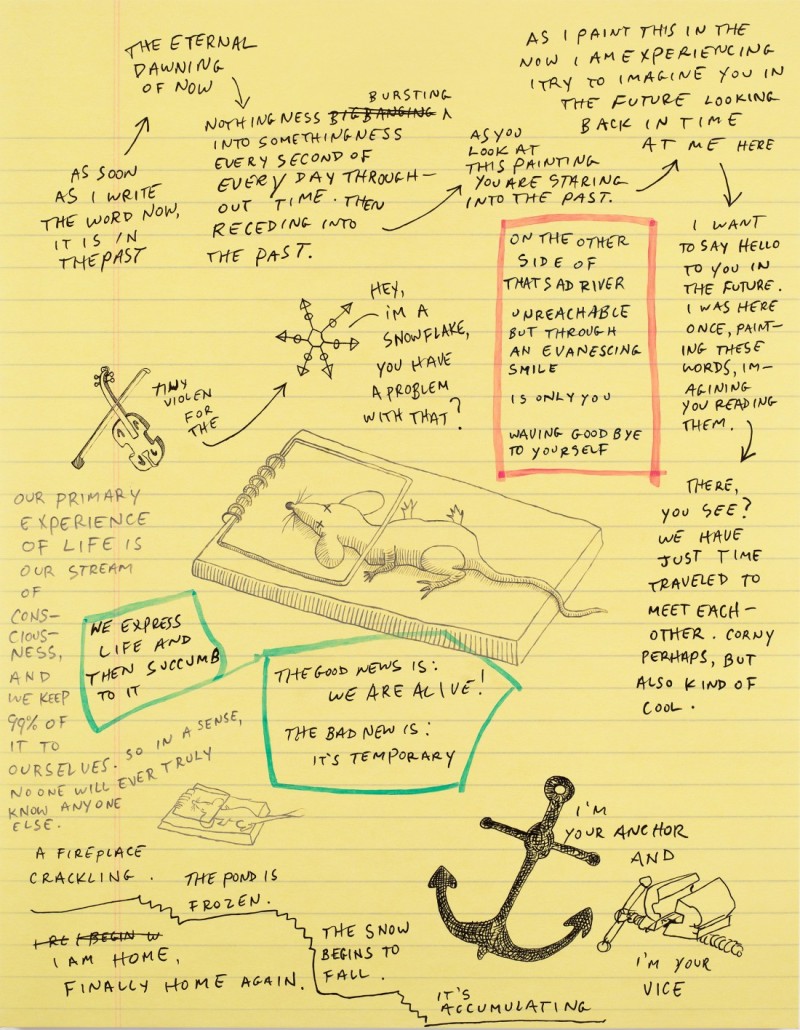

The scale and the densely autobiographical nature of Landers’s art practice make me think of Walt Whitman, America’s great epic poet, who in Leaves of Grass sang the celebratory and contradictory song of himself. There is something in the American character that wants to tell itself in a large scale, and Landers has felt some of that pull. In the process, he gets to have his language cake and eat it, too. His oil and archival inkjet on canvas called The Eternal Dawning of Now, 2017, is a collection of observations about the passing of time, mortality and the nature of consciousness. In addition to the words, there are a few drawings—a small violin to play for sympathy, a snowflake to mark his uniqueness, the warning of a mouse dead in a trap and, at the bottom, an anchor and a vise, accompanied by words that reiterate the drawing’s message: “I’m your anchor and your vice.” It is a recognition that speaks to the two functions his art performs: it secures him at the same time that it traps him. From the time he first began writing and drawing, Sean Landers recognized that he was not just a goofy clown floating on a stream of consciousness, but a wise mariner sailing on the large and more complex ocean of consciousness, as well.

The following interview was conducted in the artist’s New York studio on June 21, 2018.

Border Crossings: Do you remember the first time you used written language in a work of art?

SEAN LANDERS: It depends on how far back we go. I wanted to be a poet, and when I was a young teenager and the hormones struck, I began by writing poems on my bedsheets with a ballpoint pen. I filled my dresser drawer with dozens of poems scrawled on scraps of paper. My mother read them and thought they were really good and arranged an appointment with the most respected English teacher in my high school. So I went over to her house on a winter Saturday with 10 or 12 of my best poems. She went through them one by one and as she read them out loud, she said, “These are terrible, these are awful.” Then finally she looked at me and said, “You’re not going to kill yourself, are you?” I was mortified and utterly humiliated by her reaction. I wasn’t suicidal at all but I guess the brooding teenage poetry really got her worried. So, after crashing against that wall, I retreated back towards the safety of artmaking as my primary creative output. But the desire to write and the need to write never went away and have always been central to what I have done. When I was in graduate school, even though I was making giant sculptures in the studio, I would also be writing notes on the walls for my sculptures, or using those walls as a diary and writing creatively on them, as well. So my studio walls would have drawings, confessional writing and poetic and jokey stuff all mixed together.

Writing was a form of self-expression that exteriorized your interior thinking about who you were in the world and what you were doing?

Yes, and that has always been central to what I do. The way I like to imagine it is, all my work is a tree and writing is the trunk of that tree and the branches are all the various series I have made. All of it, every seemingly ‘out of left field’ series derives from writing—the trunk—in some way.

The branches from which you’ve grafted have been pretty various. I was interested to read that the three writers and works you talk about are Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, James Joyce’s Ulysses and Knut Hamsun’s Wayfarers trilogy. What those writers have in common is a stream-of-consciousness methodology.

Exactly. It was about giving voice to and expressing the interior voice. I first read Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, in which the narrator is the inner monologue of the main character. It woke up something inside of me that said, This is how I want to express myself in writing. It seemed as if it had already existed in me and reading Hamsun just flipped a switch on.

The Eternal Dawning of Now, 2017, oil and archival inkjet on canvas, 71.5 x 55.5 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke Studio. © Sean Landers. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York.

In Crime and Punishment Raskolnikov considers committing a crime to find a way out of his abjection, but I gather you weren’t prepared to go quite that far?

No. It was his interior life that I found mesmerizing and masterfully done. I had a different story to tell, not one about contemplating a crime but contemplating being an artist and transforming myself from the general populace into one of these ostensibly special people. The first thing I wrote and showed in New York, Art, Life and God, was a roughly hewn screenplay of an artist struggling to get into the art scene here in 1990. It was based on Hunger, where the nameless character was trying to make it as a writer in Kristiania, which is now Oslo. I simply overlaid that structure onto my life, and once I had that structure I could write about my true self. But I also fused in other fictive things and began that especially fertile mix of fiction and reality. So I would include foibles of my own—i.e., trying (and failing) to get into the art world—and foibles of my friends trying to do the same thing. For instance, one scene I wrote was about trying to give slides to Mary Boone. In the 1980s Mary Boone was this mythically huge art-world figure—so a young art student coming to her with slides was funny on its surface. I never did that but I had my character do it.

You develop this persona named Chris Hamson, an alter ego who allows you to separate your writing self from your fictional self. You sign a piece called Ouch from both of these characters. Those two people seem to have become the same person.

After a little more than a year or so, I let Chris Hamson disappear and fused him into me, the Sean Landers persona who makes art and writes. My artmaking ‘persona’ is very honest but also occasionally fictive. But mostly it’s honest. The fictive part makes things more interesting, but it also provides me with a fig leaf to hide behind. Also, the threat that I might not be honest has allowed me to be far more honest than I possibly ever could be. I think all artists need to step into the role of who they are or who they are perceived to be. I wrote in one of my paintings from 2014 that being an artist is in some way performative, and when I walk in here to my studio and go over there to paint, there is figuratively a small stage that I step onto and perform the work of my character.

All the writers I know tell me that at a certain point, the story actually takes over and then they are not in control. In Art, Life and God and certainly in [sic], how much control were you prepared to exercise over the actual act of writing as you record the minutiae of your life?

With [sic] I battled for control and I feel that I lost. It was difficult because I tried to do such a crazy thing—exposing myself to that degree. It’s a genuinely humiliating book and it causes me great anguish every time it gets attention. Recently Matthew Higgs from White Columns organized a reading and initially I was thrilled and flattered that he wanted to do it, but then it actually happened and I had to hear that book read out loud by 20 of my friends over the course of several hours in front of a large audience. It was pure torture for me. But I also understand that [sic] is the one book where somebody went all the way. I mean, what other book is like that? So I’m proud of what I did and deeply ashamed at the same time.

The conceit in Ulysses is that Leopold Bloom records every aspect of his inner consciousness over a 24-hour period. So the structure of the book is determined by the duration of a day. Were you concerned with what the structure of [sic] would be? You didn’t use Ulysses and the Homeric myth as the foundation for your narrative.

I thought of my effort in terms of an odyssey, but my working premise was that it would be purposefully comedic in comparison with what Joyce did. But I was thinking in that way, not only for [sic] but in most of my artwork, that you the viewer/reader are with me as the clock ticks, and I wanted to entertain you as much as I could but I was documenting real time passing by. It was kind of a reality novel in which I documented everything I thought or experienced while holding the pen. I brought the reader with me through the mania of my real-life lovesick drama to the lows of the bored meanderings of my mind while waiting at the gate for a flight in an airport. I had wanted [sic] to be 1,000 pages when I started out, but I had to write so many other giant extemporaneous artworks at the same time that mental exhaustion set in and there was also so much emotional exhaustion caused by my personal life. So I just had to end it because it was making me crazy.

You say you were embarrassed by it but were you aware how far you could push the audience’s tolerance? I’m asking because I did read through [sic].

Then I owe you an apology.

No, no. I’m intrigued by the strategy of composition and whether or not it was more a question of getting the book and its content out than a question of thinking about what it was going to be as it came out and what effect it would have on the reader.

The way I felt about it was that it was a conceptual exercise. I set out to fill 1,000 pages of yellow legal pad with stream-of-consciousness writing. I expected a reader to take that for what it was. Essentially, you were walking with me through time and I was being as honest as I could be. It’s the same process when I am painting/writing a giant unstretched canvas, such as For the Love of Nothing (1994), or for any one of my other big stream-of-consciousness paintings. It’s the same style of writing. Whatever is occurring to me is occurring to you while we go through it; we are passing through time together. I wanted it to be interesting for everyone, but I also knew the structure would probably include a lot of flatland. But that’s the reality of life. One of the things I thought about early on and what I got from the authors you mentioned was that the primary experience of life is the stream of consciousness. No matter what we do or experience, no matter what we look at, we’re looking at it through the scrim of our thoughts going by. I recognized that this constant flow of thoughts was an incredibly abundant art material that no one really uses. So I wanted to use it and I have been using it my entire life. Sometimes it is not stream of consciousness; sometimes it is active writing where I’m editing and boiling things down so that they are more purposeful, meaningful and, I hope, easier for people to read. But there are times where I want to let it go feral as well. All those giant paintings are extemporaneously filled by me just standing with a pot of thinned-down black paint and a tiny little brush. That is in fact where the idea for the rowboat clown comes from, because standing in front of a giant empty canvas and filling it up with a tiny paintbrush feels like rowing a boat across an ocean. It becomes very existential very fast.

When Performance Becomes Reality (Pony), 2014, oil on linen, 55 x 72 inches. Photo: Larry Lamay. © Sean Landers. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York.

In the tradition of picture making, it has aspects of outsider and psychotic art as well. Writing these massive, monumental paintings means you could be out of your mind. You don’t seem to be.

I might have been a bit out of my mind when I was younger and filling up those giant things, but of course I was fully cognizant of what I was doing. Although I will admit that there was certainly a therapeutic aspect to it and I think I benefited from it. Maybe I didn’t go insane because I went through that period of writing so much.

In [sic] you are full of aspiration, saying that you want to save American literature, and then you add that the first thing you should learn to do is to spell. Why are you such a terrible speller?

I don’t know. My dad was a very smart man and he was also extremely dyslexic. I never was diagnosed as dyslexic and never had problems in school. I was, in fact, an early reader but I might have inherited a bit of his dyslexic legacy. I don’t know what to say other than I just don’t spell well. Perhaps if I cared or thought it actually mattered, I would have made more of an effort.

But you do get wonderful effects from it. Like with “angles” and “angels.” So you don’t purposefully misspell; you just can’t spell?

I like to think of them as Freudian misspellings and sometimes they are triple entendres, which is wonderful. My book’s title, [sic], is a triple entendre. But what can I do? I’ve actually gotten much better and now with computers and iPhones and iPads, I can clean it up.

…to continue reading the interview with Sean Landers, order a copy of Issue #149 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!