Too Little and Too Much, All the Time

Charline von Heyl and the Life of Painting

I find an irresistible pull to the state of immanence. Think of Wile E. Coyote, always on the brink, shooting across the mesa in pursuit of the Road Runner, then teetering on the edge of cognition as the canyon floor beckons below. Charline von Heyl creates an interesting tension between accident and intention in her work and where Wile E. goes over, she pulls back, teasing the line between the desirable accident and the control she finely maintains. We watch Wile E. over and over in countless cartoons, hearts thumping on his behalf, enjoying the anticipatory “what if” as his hapless momentum carries him into a temporary oblivion. Von Heyl, however, holding to control reels it in and the work is complete. The teetering keeps us breathless, keeps her engaged, keeps the paintings alive.

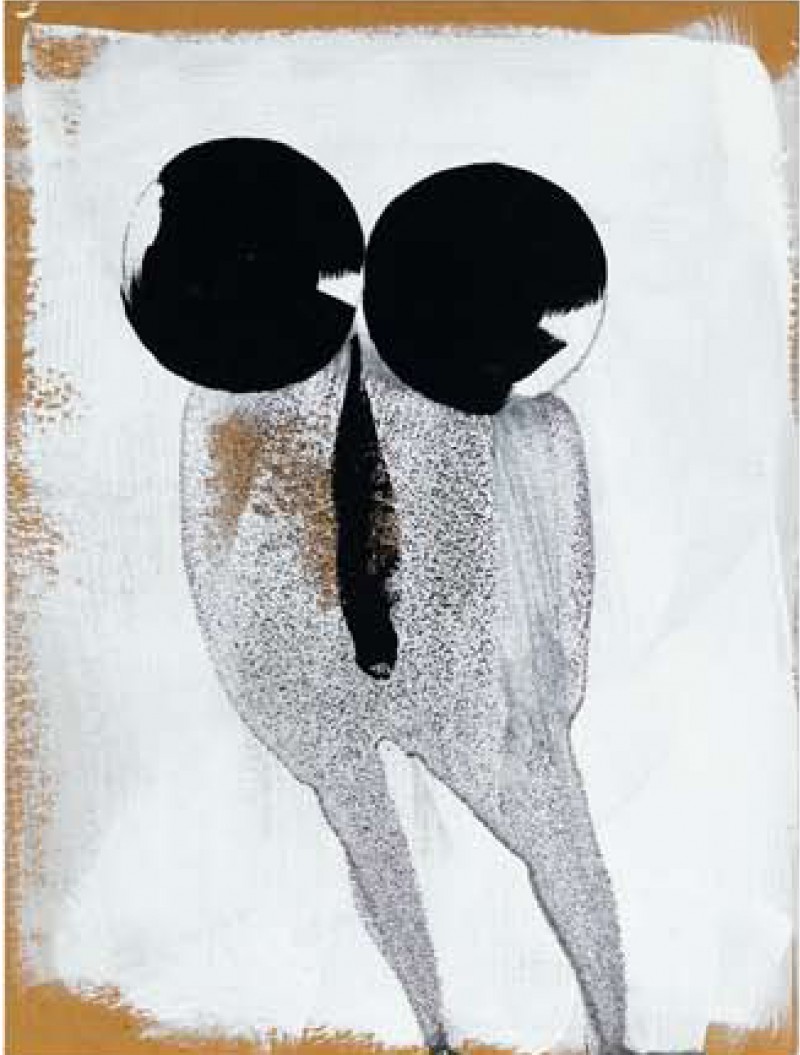

Charline von Heyl, Night Doctor, 2013, oil and acrylic on canvas, 82.5 x 68 inches. All images courtesy Petzel Gallery, New York.

In the interview which follows, the question is asked, “I look at your work and I know it’s not abstract because it is something. I haven’t found the language to describe what’s there.” In an earlier conversation with writer Kaja Silverman (Charline von Heyl, Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 2011) von Heyl makes reference to certain philosophers—she names Maurice Blanchot and Martin Heidegger—who speak in the way her paintings do. She talks about their generating an image of an idea which she says “provokes an emotional gut reaction of the mind.” It’s no more paradoxical to think of the gut voicing the mind or the head stating the experience of emotions than Charline von Heyl’s saying that what she wants a painting to act out is a self-conscious urgency. To the philosophers’ language conjuring an image of an idea, von Heyl applies the emotional state of pathos, an oddly enlivening notion. At her core of being is a feeling of falseness which, in the conversation with Kaja Silverman, she says is the “one truly existential sense of self left, or possible.” I read the feeling of falseness as a contingency which means its obverse is also possible. If it’s wavering between what is and is not, between real and its alternate state, it is the either/or fulcrum which allows immanence to slip in. Her paintings give me that. This is where they are abstract—abstractions of ideas and states made visible.

She answers the question posed earlier in the interview below: “You are aware of the fact that you are looking at something that you cannot describe: that you can only understand or not understand. So you are arriving at a knowledge that cannot be translated into words.”

In a new painting, mural, frieze, billboard—horizontal like a landscape seen from a moving train and titled Interventionist Demonstration (Why-A-Duck?), in spray paint and acrylic on linen, we have 17 feet of urgent activity in an unaccustomed palette, with the exception of Untitled (1/1/06) (aka: Greetings), 2006, which also used chartreuse—the colour of absinthe, pink and some muddier greens. In Why-A-Duck? there is also a small orange duck partly occluded by two spheres overriding his space, a six-armed, irregular star holding centre court and patterned perhaps like a giraffe or a tight tiger, and very many horizontal bars, which Corbett vs. Dempsey, the Chicago gallery where the work was installed in early summer, 2014, describe as “bumper-sticker-like banners,” most carrying text rendered in bold black lines. The duck beaks up to one of them on which a decorative pattern rises, a dark blue serpent dotted at each dip in the same clear blue. But that’s far from all there is to see. Language is everywhere, but not carrying information to be apprehended in words. Only DUST ON A WHITE SHIRT could be discerned. There are words, maybe slogans, descriptors but not language. Also a bar with a stretch mouse, like a hieroglyph on an Egyptian tomb, a coyote or an aggravated ground squirrel, a band of paw prints—maybe, two sets of lilac locomotives rushing by across a desert plain, the ultimate in horizontality and pinning it all down, if that can be said with finality about any of von Heyl’s work, are right-angled interventions like a draftsman’s T-square.

This long painting was accompanied by 40 small, black and white, acrylic and charcoal works, 12 by 9 inches on cardboard panels which speak as though they were written, and a catalogue laced with excerpts from the George Herriman comic strip, Krazy Kat, which ran in American newspapers for 24 years starting in 1920. It was much loved by writers and presidents alike for its presence as an artwork and its intellectual acuity and wit. Three characters played for the duration: the affable Krazy Kat—not definitively girl cat or boy cat, the intense Ignatz Mouse and the dutiful police dog, Offisa Pupp, parties to an unresolved love triangle. While an equilateral triangle can rest solidly on any of its sides, it teeters when only on a point and the relationship of three (two to one or two and one) is destabilized—an attractive sway or swing for an artist who works with intention and courts accident.

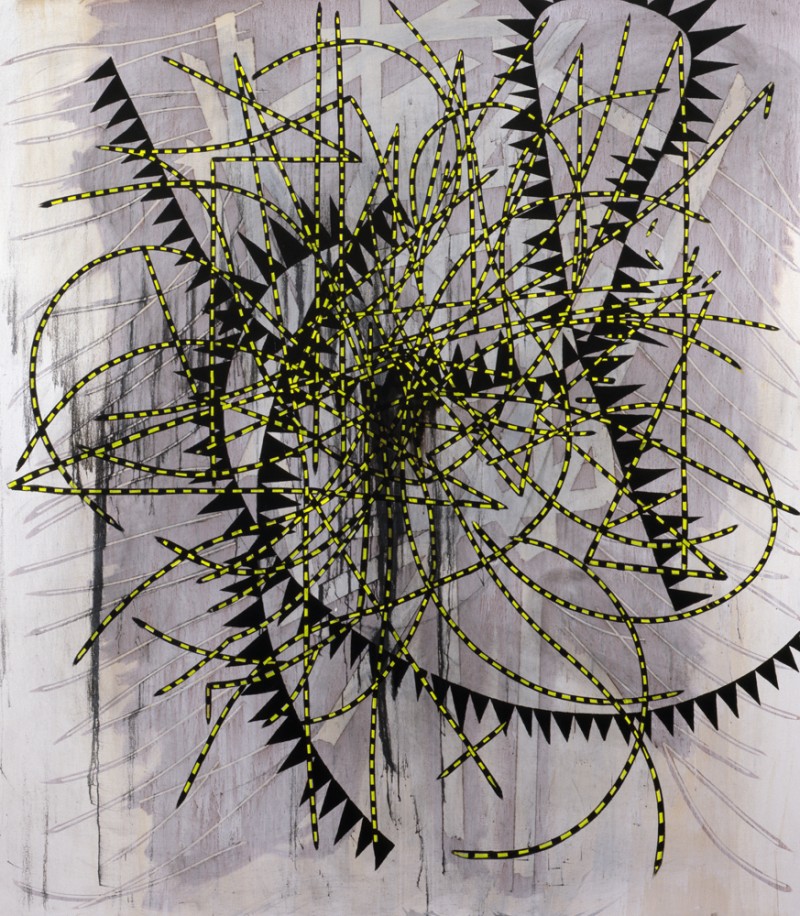

Electric Tree, 2013, acrylic and spray paint on cardboard panel, 12 x 9 inches.

When you are confronted with a 17-foot-long painting you read it in whatever way you would read that span. From the moon, you could see it all at once; nearer, you pick your spots, you focus on details. Von Heyl thinks often about the viewer. She hopes each will learn something about themself, not about her. For an artist who identifies an interest in control this is a generous giving-over, allowing the assembly and completion to be individual. She said, “I believe that in the end painting is not the sum of its parts; it lives on as an offering to choose from; by choosing you make your own painting,” and she adds that the apprehension is always of a detail, a part, an atmosphere.

It’s Vot’s Behind Me That I Am (Krazy Kat) is a large painting, almost seven by six feet, from 2010, which carries the unarticulated narrative of its title. A three-dimensional brick painted in reverse perspective moves toward the viewer like it did toward the head of Offisa Pupp for 24 years. Behind von Heyl, as for us all, is the past, our history which is also our present. If it’s a knock in the head from behind, for so long as it hovers we won’t know, but we’ll be thinking about it now.

What is also the past for Charline von Heyl is the state of perpetual play that was her childhood condition. She told us, “to paint, for me, has always been about the possibility of forgetting myself”—that timeless, endless present in which children are engaged. There were no contingencies then, just a state of pure feeling, “this initial moment of sincerity and freedom”—a medium, in the sense of suspension and its attendant youthful rapture, which she seeks to recreate with every painting.

If she allows or hopes that each viewer creates the painting, she also says the paintings make themselves. She’s grappling here with the moment (again, that immanence) when work moves over from fine and competent design to art. When is it that this action, which is troubling for her in its market consequences, takes place? What impels it? Her buttress against her own questioning is her rigorous eye trained and narrowed on authenticity and the awareness of what she identifies as the issue of surplus value. Where is it that it happens, at which point does it take place? If she blinks she misses it because she asserts that the painting makes itself.

Dude, 2013, acrylic and charcoal on cardboard panel, 12 x 9 inches.

If you were to ask—as critics, readers, viewers all do in front of a painting by von Heyl—under what conditions, in which situation, to what entity would this acutely intelligent, alert, informed artist cede control—it would be in giving over to the painting itself. There’s the bell-clear expression of a painter’s morality in this.

Charline von Heyl lives and works in New York and Marfa, Texas with her husband, the painter Christopher Wool. This interview was conducted in her New York studio on June 18, 2014.

Border Crossings: For me, your paintings remain perplexing and unlike anyone else’s. Do you feel the same way about them?

Charline von Heyl: In a very simple and embarrassing way that might be the original desire. It comes from the surroundings where I grew up. I remember this feeling of being influenced and wanting to be part of it and then realizing that if you go with something, then you are never going to be part of it. The fact that you are different is what will allow that to happen because the stakes are higher. This painting from 1996 I painted in Düsseldorf and I made it deliberately strange. At the beginning that was very much the tenor of what the paintings were about.

About cultivating strangeness?

Yes, about finding the other, the other image, the other way of putting them together.

In the 1990s the work was also denser with incident.

It was totally constructed and that was its strength and weakness. I used composition as a tool. I wanted to use strange composition but at the same time those very early paintings were about the satisfying aspect of composition, the way that it made a point about its own composition. There was a straightforward link to that. Then coming to America was so much about being cool and forgetting about composition; it was about getting loose and getting free. But secretly I have always been drawn not only to paintings that rely heavily on composition, but to paintings that do so while they make believe they don’t. That painting here on the wall had a very, very complicated composition that I really liked but it became clear that I would never get out of it. So then I thought, “Okay, I’m just going to paint,” using my tricks and all this strange stuff, and when I was halfway done I thought I probably can do something with the painting now that it is completely ruined. The next step is going to be more interesting than if I had finished my thought.

You say the same the thing about Carlotta, 2013.

Carlotta was very successful in the way that I fucked it up. So in this painting here I started with the concept that I wanted to make a perfect painting like Carlotta again, and it really failed. I realized in the middle that I was wasting my time even thinking about going there because Carlotta had taken me through a similar string of accidents but in a completely different direction, and I cannot deliberately replicate that string of accidents. So the intention killed that painting in its baby steps. In the end, this is going to be a completely different painting from Carlotta, even though the intention at the beginning was to get to a similar point.

You’ve talked before about your wish to forget the way that forms function. But aren’t they always operating as some kind of residual memory? How do you resist your own memory in the making of paintings?

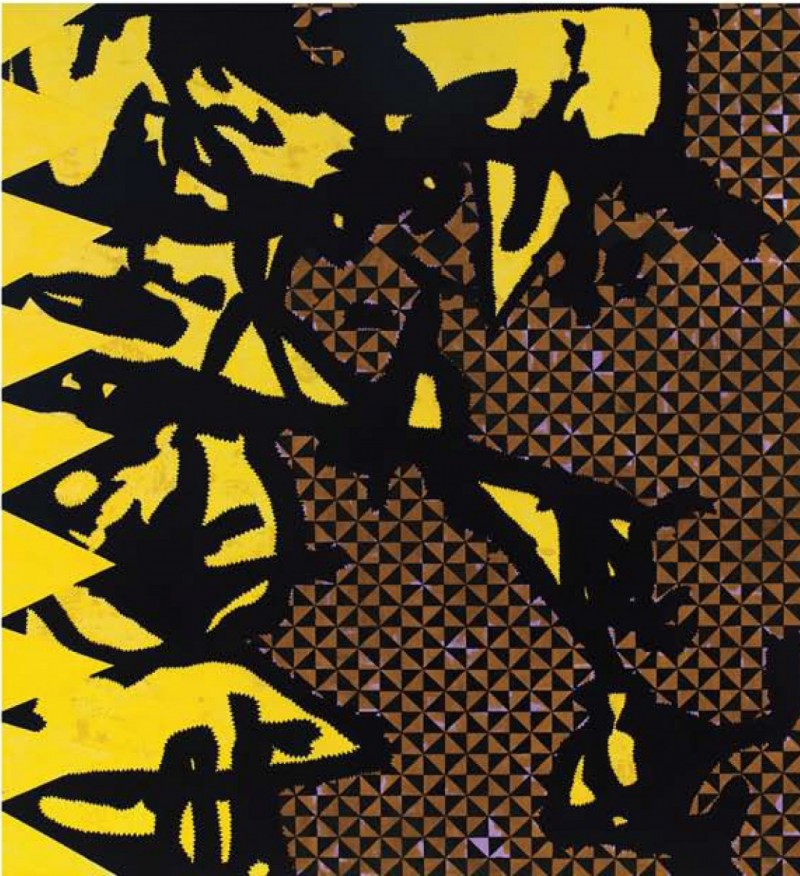

Big Zipper, 2011, acrylic and oil on canvas, 86 x 78 inches.

Memory in painting is an interesting thing. I got to be a painter to begin with because I wanted to relish the freedom of forgetting. To paint for me has always been about the possibility of forgetting myself. In those very precious moments that people call inspired you forget the world and you forget yourself and you are just there alone with the painting and the happening. I think that actually comes out of how I was as a child. I was happiest when I was forgetting myself in play, and the sincerity and freedom of playing is something that I see now as a thread. I never wanted to grow up. That is actually true. As a child I wanted to keep in my universe and painting was a way to do that, to hold on to that fantasy in a certain way. Obviously, once you’re out in the art world—which is a real world in its own way—it all changes. As a student you make decisions that are already putting you on a different course. You choose your teachers, your friends, your gallery. You consciously start making yourself as an artist, and every year it changes into something else. Your priorities shift. I am a very different artist than I was 20 years ago because I have been a teacher and I have had different relationships that were very important to me. But I think that as a painter I want to go back to this initial moment of sincerity and freedom and that is why I am so stubbornly creating that fantasy with every single painting. Every painting is a “pretend” world in a way. I can go in there, just as I did when I was playing as a child, and say, “What if.”

So that’s what you meant when you said at five years of age that you wanted to be a painter. Painting was the vehicle that would allow you to remain a child?

In retrospect it sounds like a fantasy, but being an artist was the only thing that I was absolutely sure about. It is hard to pin down because it was not an ambition and I certainly wasn’t in it because I wanted to stand out or be somebody special. It may have something to do with an early desire to protect my play ego. I never had an awesome talent. My parents would say otherwise, but I never felt that I was blessed with some gift that would turn me into this great artist. I always thought that I was underprivileged in that way and I think that was also why I never tried to even go there. I never went through the steps of doing representational work and breaking through to abstraction. From the very beginning, I used colours and shapes in a sculptural way. I thought about what happened when I put them together and then I exaggerated that a little bit because I thought that was the thing that made me different from the other artists in the ’80s. I was building a painting instead of expressing myself. But the building was secretly like playing; it was like building little houses. So I got the best of both worlds.

Was your family interested in art?

Well, they were members of Griffelkunst. It was a club in which you paid a monthly fee and German artists would be asked to do prints and then four times a year there would be an exhibition and you would go and choose prints for your house. Everybody participated, including artists like Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, so over the years they accumulated a great collection. It is funny, Griffelkunst asked Christopher and me not so long ago to do something. It is still supposed to be for people with low incomes, so now they have a whole system of protection so that people don’t buy the print and sell it on eBay. But I remember when my parents would take the old prints down and put up the new ones. They tell me that when I was four years old they had all the prints on the floor and I came in and erased all the signatures.

You were initially rejected from entering the Kunstakademie in Hamburg. How did you finally get in?

I ignored the rejection letter when I got it. I didn’t tell anyone and I put up my desk and after half a year everybody was in love with me and then it was too late. I was still not making good art, but they took me for real because they thought that my move to get in was worthy of an artist. I remember the excitement I felt in my guts, wondering how long it would take them to notice. There were some interesting artists; I thought Franz Erhard Walther was fantastic, and he was the first artist I ever talked to about my work. He would look at my drawing for one second, then turn it over and talk excitedly about the beauty of the backside. And that was actually important. The first year emphasized art history and was very theoretical. I did this thing about Kant’s aesthetic and at the same time I was making these very expressive paintings. They were horrible. Then Immendorff came and I started to really paint. He was crucial because he was the first artist I respected.

What was it about Immendorff that impressed you? Had he done the Café Deutschland series at that time?

It wasn’t what he was painting; it was his energy and his determination. It was what he had to deliver as a presence. I suddenly realized how being an artist and making art is one thing. Presence was something that I wanted the image to carry. I remember this period as the one in which I shifted everything towards the work. I had to make work that was present in the room in the way that I would love to have been, but couldn’t. Maybe that was the moment when I became a real artist.

The art scene in Germany at that time has a reputation for being high octane macho. Was escaping that one of the reasons you decided to come to America?

That is absolutely not true. Women in Cologne were very strong. Rosemarie Trockel had a whole world happening; I was best friends with Isabelle Graw who just started Texte zur Kunst. There was Jutta Koether at Spex, who was highly regarded and did the only interview with Kippenberger where he was candid and not just joking, and Cosima von Bonin was a total powerhouse. Everybody was more afraid of her than any of the boys. So anyone who was macho was confronted with a wall of very strong women. People love to say it was a boy’s club but it really wasn’t like that. In retrospect I would say that in Germany at that time it was surprisingly equal. There was a lot of pressure in Cologne but it was not gender-related. The Nagel Gallery started a whole new thing called Context art, and when I first exhibited it was with artists like Mark Dion, Andrea Fraser and Reneé Green. I was in a very strong infrastructure and it was an exciting time. I have been very lucky to be in the right place at the right time in my life. It has so much to do with luck.

You describe your earlier paintings as total constructions. Why were you making paintings that way?

Their deliberate construction allowed weird things to happen. It was both construction and destruction. Going through gesture is how you invent, and shape had already become gesture for me. Gestural expression for me is putting a shape into a canvas, but ultimately it’s not interesting because it is just the mirror of a movement and an energy. I can use that only for a moment, as a start, in the painting. I build up the shape by destroying it and by laying another shape over it. By building the painting in overlapping layers I would get shapes that I could never have invented. That’s what I wanted. There was an early desire to create an alternative mind-space in a painting. It turned out to be something that was nicely situated between the worlds; it was linked to the painting of Immendorff and Oehlen and other painters I admired, but at the same time it was conceptual in the way that it created a mind-space that was not about painting in a simplistic way but one that would put out a statement without relying on words. That was something that has always interested me.

“Charline von Heyl” installation view, 2013, Petzel Gallery, New York.

In talking about painting you also use the word bewilderment, “to be made wild.” What is the relationship between control and finding this wildness?

I think it comes from the obsession I have always had with personal freedom. Freedom is in the head and the more you can expand your headspace the better. That’s why I like to read things that are bewildering and to do things with language that I don’t understand. Even if I don’t understand it, my head feels different than it had felt before. It is still going to give you a different feeling in your head. It sounds weird but I know it’s possible to be bewildered from looking at other painting. Some of it asks, “How the fuck did she do that?” but some of it also asks, “What is it that makes the painting look so different now that I see it a second time?”

So what you’re doing doesn’t take a lot of nerve? If the painting is failing, instead of being anxious or depressed, you are encouraged.

Yes. Very early on, even in art school, I realized I had nothing to lose. The only way I could go somewhere is if I escaped predictability. I could only make myself as an artist if I found a space that others could not predict. So anything in a painting that did not bewilder me made me think, “Why do it, it’s beautiful but it’s not interesting.” I never had a problem ruining the most elaborate painting, even one that I had worked on for weeks, if it didn’t give me that extra feeling of wondering about it. I’m not interested in painting as a manifestation of successful moves.

A painting like Dunce, 2005, lets the viewer see evidence of gestural abstraction and hard edges in different degrees. There’s also dripping going on. The painting looks like a series of strategies for making a painting.

In that painting, I actually used a stencil I had made. It is not just me in front of the canvas. There’s always a life before that has to do with images and with alterations of images in my mind. All the paper works are new images created from an image bank that is already charged with a self-destruct mode. At the same time, they are very direct references; they all come from somewhere and from very clear desires. So at the beginning there is the desire to cannibalize beauty, but that gets turned into tools and the tools themselves have a beauty for me. But they are tools; they are not the end product. And I use those tools in the painting, sometimes directly like the stencil in Dunce, which is a direct quotation of an illustration I saw somewhere else. I blew it up and cut it up but for me it still carries that moment of beauty. Over time, the content of that narrative lineage becomes non-existent because I have literally made it a tool that I can use in different paintings in different ways. It is part of my universe, but my universe is made of tools.

So the drawings are generative for you?

Yes. They are a motor because they fill me with energy. There is despair in making paintings until the moment when it turns over and is suddenly being made just by me.

There was a period for 10 years, though, when you didn’t draw?

Yes, there was, I started with drawing when I was a kid and I probably come more from drawing than from painting, But I started drawing when I discovered tools again, when I began to slide drawings through the copy machine and have random prints that I could then rework. All that stuff I was doing in 2001, The next big step was in 2007 when I started to print for real. I had held back from printing for a long time, because my idea of painting is so close to printing and I didn’t want my printing talents to be used up. I wanted to think in a printing way on the paintings. Which was a stupid thing to do because they don’t necessarily take away from one another.

So printing too became catalytic?

Yes. Maybe it is like a rocket that you launch and every hundred million kilometres you need to get rid of more things in order to accelerate, But at the beginning you instinctively don’t throw off all the parts that you can use.

There are repeating tropes in your work—the vertical stripe, the grid, the saw-toothed shape. Are they elements of a vocabulary that you reuse in your quest to find new things?

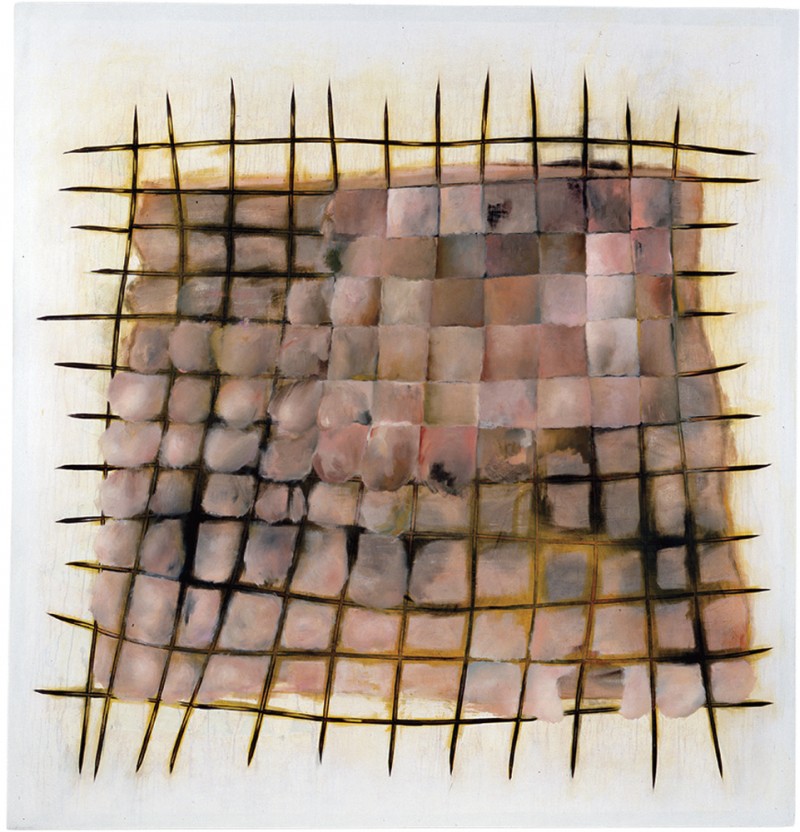

Concetto Spaziale, 2009, oil on canvas, 81 x 74 inches.

In a certain way, this desire for newness is also a fantasy. People pick on it because they say everything looks so different, but I think my paintings are easily recognizable. I don’t deliberately take on styles or anything like that. As for those signifiers you mention, they are powerfully charged. To put a zigzag line into a painting is like adding a lightning bolt in a comic way. They are very simple, powerful structures that always represent a point of failure in my painting, because I use them when I think I can’t get any further, when I don’t know what to do anymore. So instead of ruining the whole painting I decide to put in one of those things—either a stripe or a zigzag line. Often I overpaint it. It is so much like a synonym for aggression, it’s as if the painting feeds that aggression back to me. I get uplifted into a new energy and the painting is energized through it. I try not to put them in, but I like them. My dirty secret is the word that I need to survive: authenticity. At the same time, I have always insisted on the fact that in the end the painting is a completely finished and determined solution to something that talks to other people about themselves, and not about me.

When I first saw the zigzag line I thought you were making a reference to Giacometti’s Woman With Her Throat Cut. It is such a powerful use of that serrated edge.

I probably am an abstract painter in that I do not attach a narrative to things. If there is a narrative in the painting, I use it only as a tool but not as an argument. I find paintings interesting as long as they have a lot of tidbits of information. Paradoxically, I also see myself as a non-abstract painter because I am not interested only in forms and in the way that a surface can be altered. It has to be more than that. It has to congeal into an image and my desire would always be to have it congeal into an iconic image. And that is not so easy. It happens in a body of work maybe once, and people always see it. In my last exhibition at Petzel, Carlotta was the painting that people saw in that way. In the best of worlds, I would love to make only paintings that have this very strong iconic quality and I’m certainly trying for that every time. But you cannot have a meal and have your taste buds super excited at all times. You wouldn’t want to eat any more. You also need bread and butter. So I need and love my bread and butter paintings and I would probably prefer to live with one of those. But I aim for the creation of an iconic image that does not rely on narrative.

You say you stay away from narrative, but your show at Petzel in 2013 included a skull, a traditional still life and a painting with black fingers. Those seem to be more direct representations than we have seen in your work for a long time. Does Skull, 2012, get named after you have made the shape? What is the relationship in your work between painting and naming?

The answer to the last question is that it’s always on the edge of the knife blade. All that is interesting if I can use it, and it might fall on one side or the other. I’ve been looking at painting my whole life; I am a voracious consumer of images. The more you look, the more you become the kind of connoisseur who understands that a still life is not a still life. A still life is a means of a structure and it takes a long time to understand that. You look at a still life from Caravaggio or Ben Nicholson, or some artist you never thought about before, and in being confronted with the question of how to deal with this vehicle you realize that you are not the only one who makes and uses tools, and turns them into ideas and images and desires. You realize that those tools are used in different ways by other artists. I have never thought about making a still life but I recognize the idea of a still life as a tool. Can I borrow that tool? That’s what happens and it happens more and more and adds to the excitement of carving your own tools.

The names of your paintings, though, are quite evocative and deeply suggestive much of the time. You have a painting called Medusa, 2006, or you take the short story, “The Unknown Masterpiece,” and feminize the name of Balzac’s main character in Frenhoferin, 2009. Those are both loaded moves. Do you intend them to be instrumental in the way we read the work?

Frenhoferin, 2009, acrylic, oil and charcoal on linen, 86 x 82 inches.

Yes. It’s not that often that I do it in such an exaggerated way and if I do, it accompanies an exaggerated painting. It needs that counterweight. The painting came out of Jean Didi-Huberman’s reading of Balzac and then my reading of Balzac, and thinking about how it has already been cannibalized by culture, like in La Belle Noiseuse, 1991, with Michel Piccoli. Many minds that have read the short story over 200 years have tried to figure out in their heads what that painting looks like. I mean, it is so vividly described. What I was obviously trying to do was to translate my own imaginary painting into the world. I wanted the link to the history of that story.

In a painting like Untitled (1/1/06) (aka: Greeting) you build in that beautiful flesh-coloured section, which looks very Matisse-like.

That was a total Matisse reference and it had another title, The French Painting.

That interests me because you have been very open in your references to other painters. You have a piece called Concetto Spaziale, 2009, which comes straight out of Lucio Fontana, and Yellow Guitar, 2010, is the name of a painting by David Hockney. When you make those kinds of references are you providing clues for alternate ways to read the painting?

Pink Vendetta, 2009, acrylic and oil on linen, 82 x 72 inches.

I have very ambivalent feelings about Hockney, but you can cherry-pick some amazing stuff out of his whole body of work. I loved those stage sets he was making in the ’80s. I wanted to translate their kind of exaggerated surface artificiality into my painting. So I chose this title to acknowledge my debt, but also because it is such a ridiculously generic still-life title and the painting was a take on still life, even though there was no guitar. The titles usually come after I have made the painting when I realize that it probably has more to do with the images I looked at than I thought. So it’s always a bit of an homage where I say, “Okay, this was not just me on my own here.”

I sense that the homage to Fontana that comes up in your naming recognizes the imminent sense of danger embodied in his work. At any point in the cutting he could kill his painting.

Yes. He is a dandy who paints in a suit and yet the paintings are so charged. And at the same time it sounds so good—Concetto spaziale. I’m stealing the aura of that title and adding it to my painting. I like the association. Sometimes it is just that kind of cannibalism.

That is also part of the fun. It seems to me that you are constantly on the lookout for joy in the work, although you would use the word desire, which is more complicated than simply having a good time.

There are so many different joys in being a painter. I have discovered that since we are all in a community of artists—it doesn’t have to be painters because some of my favourite artists are not painters—one of the most satisfying sentences of complete joy is, “Take that.” If you’re having a show you’re going to up the ante on some level just for the sake of “Take that.” That is the reality. You try to give the work that extra edge, take this extra step, because you know that the stakes are high and that there are really good people out there and you better get your shit together if you want to compete.

What compels you to come to your studio every day?

I think it is probably the joy that with every successful painting you realize you have added something to the world. You can assure yourself again that maybe you are not a fraud, and that is something that needs to happen because the feeling you have is that you are a fraud, however often you do it. I think a lot of people have that. It’s weird because I have to paint again and again and again to be a painter.

So you really mean it when you say that the one authentic thing you can rely on is the falseness? You feel that kind of anxiety in the studio and more broadly in your life as an artist?

Yes. In the paradoxical and, in many ways, anachronistic universe of being a painter, you feel extremely fragile and you can only counteract that feeling with invented pathos. It can no longer be the real pathos of Jackson Pollock. It has become more of a signifier for pathos. I think the anxiety is the same but we are no longer allowed to give in to it and express it in the same way.

Coming over to your studio, you told us you are worried about the state of painting.

I was talking about abstraction. There is a lot of anemic abstraction out there, but in general I see so much great art being made. The situation in Cologne was very vivid and important but it was also very small. The art world today is a big world and it is amazing how many people make really good work. I think the hierarchical thinking we have about art is changing. There is no spearhead of the avant-garde any more. It is more about choosing. If you are interested in art you can find something that is absolutely special, something that links to your desire.

The critic Sally Simpson characterizes your work as a combination of the seductive and the repulsive. Do you feel your work operates within that complicated register of what is both attractive and distinctly unattractive?

I only find things attractive if they also repulse me.

That idea connects to a certain kind of Romanticism.

It’s very German and I think it definitely comes from the art I grew up with. But art that is aggressively repulsive or abject is very limited in its attraction. So I had to look somewhere else and I found what I was looking for in extremely good design. For me that is a more interesting kind of repulsion than the abject. The best thing is to mix those two things and the very best thing is to not have it look as if they’re mixed, to create something new out of it. So attraction/repulsion is like construction/deconstruction. They are tools. It is not making a point; it is not a narrative about ambivalence. It is about charging the painting with energy.

The Story of a Panic, 2013, acrylic, ink, wax on paper, 24 x 19 inches.

Your work is charged in that way. Does that make you happy?

It makes me happy if the paintings perform. If you make a painting perform for yourself, you still don’t know if it will affect anyone else. So I’m very happy if there is any effect on the viewer.

In making observations about your work you often use the language of drama and theatre. You just talked about the paintings “performing.” Your palette is at times deliberately dramatic.

That’s my taste. The carpet in my room as a kid had orange and pink stripes with a zebra pattern on it. Childhood things make the first impression on you. Sometimes it is as simple as that. Later you quote it in an ironic way and then it becomes part of your vocabulary. Taste is not only something that reflects your thoughts; it is also something visceral that informs your pictorial inventory.

Tell me about that the word “Miserabilism.” Where does it come from?

It is a real word, like constructivism. Miserabilism included about five artists in France, of whom Bernard Buffet was the best known. It was a post-war expression of the horror of what had been going on and the existential crisis of not-knowing how to begin again. Two of the artists killed themselves, I think. It was not high art; it was something that everybody could have in their house. You would hang a Bernard Buffet clown and it would express that kind of sadness in a very simple way. People came to loathe it, but I respect it. There is a power in that kind of expression and I think it is needed in the world. I like Buffet’s existential directness, but I’m also attracted to the way he included design. On the other side of the studio I am playing with his illustrations for “Toxique” by working into the books and I do it only for myself. His prints and drawings are perfectly designed in this nostalgic way that triggers desire in me. Just to react to them puts me in a creative mood.

You talk about design in painting, too. Is it a synonym for composition? Is design about the conscious and elegant arrangement of parts?

Maybe it is elegance in a certain way. It’s such a slippery slope because I don’t really know myself what I mean when I refer to design in painting. I know that up to a certain point you can design a painting and then some small thing gets added that makes it art. I love animated movies, especially the hand-drawn ones from the Japanese Studio Ghibli. The effort that comes into depicting raindrops falling into a lake and what happens to the reflection is so unbelievably artful, and you have all those out-there angles and eccentric compositions, and I’m here in my studio with my stupid four-sided canvas and my stupid brain and my stupid hand putting on marks. And what I do is supposed to be worth so much more. That is probably why I feel like such a fraud. Where did I slip over from design to this surplus value that makes me this cherished or interesting artist? Where is it? I always try to find that point and it always slips through my fingers because it seems to be the painting itself that makes it. The painting is always faster than me.

Blacksmile, 2013, oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 82 x 78 inches.

A painting like Killersmile, 2011, is so simple in its reduction. You don’t get much more minimal than that. But you use the smile a lot. There is Blacksmile, 2013, and in Vanus, 2004, you included a little de Kooning smile in the midst of a pink and red turbulence.

Yes. In the end I think it is the smile without the cat. But Killersmile is one of my slowest paintings. If you look at it very closely you can see that it is based on the shape of two pink triangles. Even that black shape was arrived at by moving tiny bits back and forth before I had it the way I wanted it. It was forever just the stripes. Then at some point it activated itself while I was watching. I added that point and the way it just goes over the right-hand edge. It’s one of those things. I wish I could make minimalist paintings but I am kind of a maximalist.

You say that you want to encourage the paintings to invent themselves and you also say that your paintings are like recalcitrant children in the playground. They don’t want to play with other kids; they want to do things on their own. The thing is, you’re in charge of the playground, so don’t they get to play the way they want?

When I say the painting invents itself I acknowledge that there is a moment that I don’t control, and I’m a control freak. I cannot say I lose control since I’m always watching. But it doesn’t seem to be my idea. Those are tricky registers, and I probably add to the confusion by saying the painting actually does it. But that back and forth movement does happen. I do something to the painting because of what I have done to the painting before and that lets me think about possibilities I wouldn’t have thought of if I hadn’t have seen that move. In that dialectic, the painting orders me to do something that doesn’t come from me. Because most everything I do to the painting triggers something that satisfies me. Then there will be that final satisfaction coming back from the painting. Satisfaction doesn’t mean contentment; it means acceleration.

And when do you know the painting is done?

When I actually can sit there and look at it and not get bored, or not get the desire to do something else to it, or not have the impulse to turn it to the wall. When it is something I look at and say, “Wow, I could never have done that.” Then in the fun of looking at it, the desire comes back.

You have talked before about the necessity of paying attention and it occurs to me that another hearing of the word refers to “a tension.” Is that a requisite part of what works in painting?

It would be easy to say yes but it is not that simple because everybody gets something else out of a painting. I believe that in the end painting is not the sum of its parts; it lives on as an offering to choose from; by choosing you make your own painting. What I thought was the whole is not going to continue as that construction when it is away from me. Even though I worked towards a solution, that solution is not what makes the painting. What makes the painting is what you were saying: that it demands attention but it is never to the whole painting. The attention will always be to a detail, a part, an atmosphere or a relation that you create as a viewer.

Folk Tales, 2013, acrylic, ink, wax, charcoal and collage on paper, 24 x 19 inches.

How do you feel your painting is changing? Is there a larger trajectory that you can perceive in the work?

I wish. I think that I might ultimately fail in that because I am so addicted to taking a step back once I have taken a step forward. There is always a decisive moment where you could go one way or the other way. I always go back to that crossing where I had already made a decision and wonder, what if I go the other way? I’m not aiming at transcendence and the fantasy of the illuminated late work. I am more interested in exploring than in making statements. I have never been able to long for the future and I have never been able to remember the past.

So you’re locked in the present?

Yes, in versions of the present. In a weird way it’s like a horizontal spread: versions of the present that are linked to versions of the future and the past. When I look through these books on painters, I am linking to a past. And if I talk to my artist friends and we look at each others’ work and start to think about the “Take that,” then that is a future. The past and the future are forces that move me, but it might be sideways.

When you choose to name a painting Phoenix, 2008, I can’t help but see that as a choice that comments on painting’s ability to re-form itself from the ashes of its previous existence.

That was the first painting I made that had very much a feeling of an abstract icon, almost a logo, and also the colors of the Phoenix Oil Company. So the title referred as much to that idea of a logo as to the mythology.

I read the surface of P, 2008, as a Magritte-like rock.

That’s good because it is a celebration of surface in a very simple way. Instead of the frame, it’s like an all-around crown, or a halo. P stands for painting. I always felt ambivalent about being labelled abstract because I don’t think of myself that way. There are other ways of being an artist. One is the autonomous, solitary self and the other is a witnessing self. You could argue that witnessing is non-abstract and the solitary leads to abstraction. So I would be an abstract artist except that the abstraction I’m seeing is so self-satisfied that it is a completely different world from where I want to go. I still want the work to be transformative for myself and for others. That is something the witnessing does. I want that to be in there as well. There is a narrative; it’s just not to be put in language. It’s not possible anymore to think about abstraction and representation. There are so many different dots between those two poles and all of them are really strong and they need each other, sometimes in the same painting. The representation/abstraction discussion doesn’t matter that much, and yet in talking about art it still seems to be the only game in town. So we need new terms.

Finding the language is always the problem. I look at your work and I know it is not abstract because it is something, I just don’t know what that something is. I haven’t found the language to describe what’s there. That’s my deficiency, not the painting’s inarticulation.

Well, it is not your deficiency because the paintings fulfill that need. You are aware of the fact that you are looking at something that you cannot describe, that you can only understand or not understand. So you’re arriving at a knowledge that cannot be translated into words.

But it is something you can see?

Absolutely, and what I find so interesting is that it stays a phenomenon; that it is not charged with spiritual expression, or anything like that. It really is in the making, in understanding the making, and in the actual looking that you get knowledge of something you didn’t know before. It’s fascinating and that is what your whole life is about. Your whole life is too little and too much, all the time. ❚