this to this, this to this

the interconnected world of June Leaf

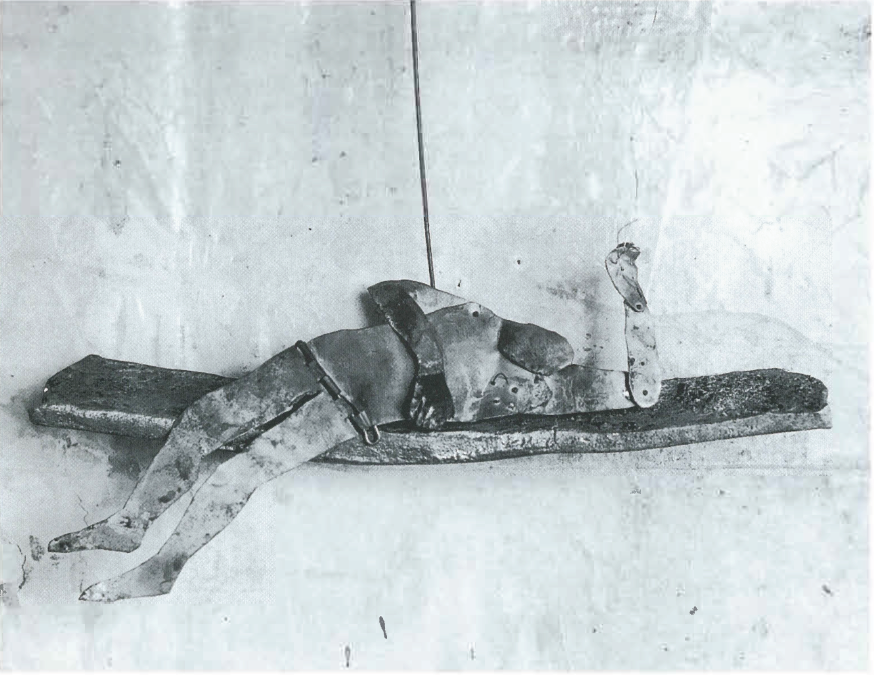

June Leaf, Red Woman Centaur, 1998, Tin, wood, pins, 9 1/2 x 6 1/2 x 2 5/8”/ Photograph: Sarah Caplan.

This is what June Leaf told us. That for her, two of the most beautiful images are a woman sweeping her hair off her neck, and the rump of a horse. She could well be right. Looking at some of her recent work I think this:

A woman wears a cotton chemise. It’s been washed and washed until it’s as fine as a lawn handkerchief. The loose garment sits easy on her slender frame and only in the folds of the dress can you read traces of the pale blue it once was. She stands by a window on a day in the accumulated heat of August. She has a moment before she needs to resume her work and she flicks her head once, and again, against the weight of her thick, honey-coloured hair. Then reaching behind her with both hands she lifts the hair from her neck and piles it on her head, holding the upswept mass with her hands. A wind, invited through the open window dries the curve of her neck where the heat from her hair had dampened it and briefly, her nostrils pick up the scent of soap and skin.

A mare stands on the soft dust of the broad, dry riverbed. She’s been following its course through the afternoon and she pauses now, comfortable in the open space that would preclude surprises. Still, the place is unfamiliar and the ease, though welcome, is tentative. The last of the sun touches her hack, warms her flanks, settles on the satin-packed volume and gloss of her full quarters and turns the chestnut to copper. With her small feet she picks out a brief tattoo, lifting a hind leg to shift her weight, picking up a foreleg in a balletic balance. The wind finds her tail and pushes it aside, carrying the scent of ripe pineapple from her quarters to her fine nose.

Sculpture Entering the Room, 1998, Polaroid and acrylic on paper, 12 x 20”. Photograph: Sarah Caplan.

It’s possible. And it’s also entirely possible that the history of the world can be written on the rump of a horse. Because June Leaf tells us so and what is written there can be enough, or it may not be necessary to write anything more than that surface can carry. The point is, you look at the work and the narrative possibilities build. For June Leaf that’s part of the process.

In the interview that follows there are references to ‘this figure’ or ‘that gesture’ and even without the visual clues in front of you, you are nevertheless drawn in, into the story, onto the stage and inside the inhabited world of Leaf’s studio. She’s a practised and credible storyteller and it’s easy to imagine the child she was, in a childhood she loved. I conjure a quiescent and agreeable being with her own soundtrack and storyline reeling inside her head, matching or explaining or perhaps running parallel to the visual world she observed–a small girl with big eyes who was told not to stare.

The narratives and the conversations don’t end with the exit or death of a figure in her life, or her work. Speaking about her father she says, “Someone will ask, ‘Was you father an artist’?” and her response is, “Not yet. We’re working on it,” so thoroughly does he remain–many years after his death–a significant presence in her life. Storyteller and playwright, June Leaf is also a dialectician, her mode synthetic. You see it in her process. She acknowledges that the making, the disassembly and then the reconstruction are her method and have been from her earliest days when she’d smash a beloved toy, loving it so thoroughly she was compelled to learn how it was made, what it was made from, what was its essential core.

Mechanics interest her still. What is the armature, the substructure of a piece, she’ll ask? And her deft and enchanting tin sculptures define for her how a painting works, define what is its support–these spare and essential tin sculptures, three-dimensional, diagrammatic models for the paintings.

In Leaf’s garden the machine is not an interloper; instead, each is what she describes as an elegant device, constructs of human mind and hand. She has said, about herself and her work, “I’m a painter, but my sculpture is my anatomy lesson,” and like George Stubbs, the renowned 18th-century horse painter who, in order to understand what he painted, undid the horse, layer by layer–skin, muscle, tissue, to the bone–Leaf moves up and back from substructure to suprastructure, from inside to outside, using her insistent curiosity like a delicate scalpel.

There are two recent bodies of work, perhaps still in process, one titled Artist studio theme, the other, Sculpture Entering the Room. Each has sculptural components–a room raked like a stage, a platform, portions of figures, a tin chair–but they are, nonetheless, through the artist’s treatment of space, paintings. In these paintings the figures are searching through narratives which are not readily explicable, stories as dialectical and open-minded as is much of Leaf’s work.

Taking up the licence the artist offers I assume there was travel of some sort–in space or mind–in search of some value. The contemplative, slow and respectful demeanour of the figures prompts me to say that what they were seeking was a truth and reentering the painting’s space, they appear to have found it.

The sense you draw from studying June Leaf’s work, from listening to her speak is that throughout–the substructure, the frame, the supporting grid–is the truth. The work has to know and understand its own function, and the integrity of each piece, the very artfulness of its essence is thoroughgoing. I think here of the manner in which she solved a problem in constructing the hand of the Red Woman Centaur. Before she was content, it was necessary that the hand be ready to do something: “She could unbutton her dress, she could put on an earring, or she could stab herself in the neck if she wants.” When it appeared the hand could do these things, the piece was done. She says, “You don’t invent anything, you just discover the truth. And that truth is always there.”

This interview with June Leaf was conducted by Robert Enright over the course of two days; the first, in December 1997 in her New York studio; the second, in that same location in April 1998.

Red Woman Centaur, work-in-progress, December 1997, New York. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

Red Woman Centaur, work-in-progress, December 1997, New York. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

Red Woman Centaur, work-in-progress, December 1997, New York. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

JUNE LEAF: I don’t think, I just paint, because where I live is behind the paint brush.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I know that painters often say their work generates a dialogue but you actually create whole worlds of possible interaction. Your figures seem to become characters in an ongoing visual story.

Only lately. Because I’m coming to the end and I’m getting all the answers now. See, I think when you get to be near 70 years old you’ve been on an exciting archaeological quest–it feels like that anyway–and you didn’t even know why you were digging. You just know you like to dig. Later you start putting things together and they pile up and look like buildings and houses and streets and places. They even start looking like what’s around you at that very moment. It’s like a puzzle coming together. I’m just excited. I didn’t know I had questions and I didn’t even know I was looking for this man that I’m documenting now in my painting.

Are you working on a diary of his life?

Who he is, what he means to me. Maybe that’s who I was looking for. It’s not God or anything; it’s just some essential thing that I’m fortunate enough not to have been supplied with, but have been fortunate enough to have found on my own.

Let me go back to your childhood. I don’t know much about what it was like for you growing up in Chicago.

I was a kid and I just loved being a kid. I was surprised when I was supposed to stop being one. But I found a way out of that.

Your father owned and ran a tavern?

My grandfather came to America from Kiev when he was about 18. He was married, my father was already born, but he came alone and lived in New York with relatives for two years. He went back and he and my grandmother had three or four more children and then he moved to Chicago with my father, who by that time was 13. He was a very capable man. They had a cigar store; then they made a liquor store. In Chicago liquor stores and taverns go together. My father didn’t really like work very much because he liked to gamble. We’re very similar. What I mean is that walking the edge and living for the moment is very much in me. I don’t know about gamblers but maybe he should have been an artist. We were so much alike that sometimes–and I wasn’t with him very often–it was like he was my shadow and I was his shadow.

Did your father make a lot of money and then lose it because of his gambling?

He made enough money to lose; when I was about three my mother had to take over and do the work. So she worked every day behind the cash register in the tavern.

Would you have been the only Jewish family in Chicago running a tavern? That’s not a normal Jewish occupation, is it?

That’s true, there were no others. Except I had an uncle who also had a tavern. Our family was into taverns and they made a good living. My mother was–and is–a hard-working woman and my father was a very amazing spirit. I’m happy about him. He died in 1970. I know this sounds real crazy, but I feel I work with him. Someone will ask, “Was your father an artist?” and I say, “Not yet. We’re working on it.” He was maybe a little lazy but he had amazing fantasies. I was the only one who seemed to take him to heart.

Pencil Legs, 1980, coloured pencil and ink on paper, 10 x 8”. Courtesy: Edward Thorp Gallery, New York.

Red Woman Centaur, April 1998, painted Polaroid. Photograph: Sarah Caplan.

You’ve also said that “an artist is given one thing in their life to do, and mine was to recognize that so much of what my life was about was the love of women.” You were talking about your grandmother and mother.

That was when I was working on the Treadle woman. That’s love of everybody really, as if I could burst into song.

But you didn’t talk that much about the patriarchal side of your family, so it was intriguing to hear you tell the story of your grandfather reading the Talmud and telling you that God didn’t exist, that God was in you.

Matriarchal societies don’t allow for men. It’s funny because before I would visit my mother in Chicago I would say to Robert that I’d like to go to the cemetery to see my father’s grave. He would tell me to say to my mother, “After all, I’m half him.” I knew there was something wrong with that remark but I decided I would say it anyway. So we were in the kitchen and my mother was chopping onions. She had a knife in her hands. And I said, “Maybe we could go out to the cemetery.” “What for?” “Well, I think I’d like to go to the grave.” “Too cold,” she said. I said, “Well, you know dad is half me.” And she took her fist and she banged it on the table, “That’s not true, you’re all me.” I remember thinking I wasn’t so stupid after all. But because she’s very bright and a very balanced person, she realized she was wrong when she said it. But that story tells you a lot. My grandfather would never talk so that’s how he got around the women. He had a way of just doing things, executing the important decisions, guiding in a way. When I was 28 my grandmother died and my father said I think it’s time that you, of all the children, spend time with my father. It will be good for him. I was getting ready to go on my Fulbright to Paris so I said okay. I was single and he was mourning. He would come over every day, we would do things and we got to know each other. Then I went to Paris and we began a very beautiful correspondence. It was like a love affair. In one letter he wrote, “You have strength like the grass that breaks the cobblestone.”

Embarking, 1994, acrylic on canvas, 56 x 95”. Courtesy: Edward Thorp Gallery, New York.

Did you actually decide that you were going to be an artist sitting underneath your mother’s sewing machine when you were three years old?

I didn’t know that’s what it was. I just thought, I love to make things with my hands and I’m going to make everything. In my case, it probably had to do with my mother who I was very much in love with and she was very much in love with me. She was like the sun to me, she was everything. And I think I still am in some way to her. But then my mother had to go to work and I never saw her again in the daytime. The part of the story that’s really interesting is that the first thing I decided to make was a high-heeled shoe because my mother’s feet were down there. She had leather shoes on and I loved her feet so much. I thought, “I don’t know how to make the heel and the toe.” I remember that day very well because I never used to have to ask my mother for anything, but this was a very important day because my life’s work was about to begin. I said, “Mother, draw me a high-heeled shoe.” She walked across the room and got a pencil–which was really nice of her–she came back and made this drawing. I looked at it, and I looked at her, and I thought, she doesn’t know how to draw a shoe.

Were you doing visual problem-solving, looking to see how to make the toe?

When you have language that’s when you have your brain. I had an interest in how things are made on paper. That’s my talent. So I looked and I said the toe goes on the ground like that, then I looked at my mother and I looked at the shoe, I thought about my life’s work ahead of me, and I thought maybe she doesn’t want me to do this. Maybe because she doesn’t like to do this she doesn’t want me to do it either. But I have to, so I’m not ever going to tell her what I want to do. I concealed it and I learned I was right. She’s very forceful and likes to mould people.

It’s a strangely ambiguous epiphany you experienced; it becomes your life’s work and it also becomes the reason you have to shut yourself off.

The tussle between the daughter and the mother is not such an unusual thing. I think the drama was my mother having to leave me to go to work. That’s probably why all these things were so memorable because they were my last times with her. It’s scary how my memory is so clear.

You’re very good at doing high-heeled shoes.

Oh, I love high heels. Don’t you? I mean the foot of a woman in a shoe is just a beautiful thing. I like all feet, anywhere. I don’t do them so much any more. It has to do with what it’s like to wear a shoe. You feel your foot, you feel your weight on it. It’s such a visceral thing. You should try putting on a pair of high heels, you’ll see what I mean. There’s something about putting your toe down on the ground and raising up your body. It makes your spine act a certain way.

You seem to have done everything precociously. You end up teaching at the Art Institute in Chicago when you’re only 23.

Friends said it was meteoric. I just had a straight line you know.

Did you want to teach or did you teach to support your habit of making art?

The teaching was the way I supported myself. Then you didn’t have to have degrees and I had already done good work. Moholy Nagy’s idea was that if you were a student at the Bauhaus and did well, then you were exactly the kind of person he wanted to come back and teach. I only went to that school for three months but I ran into my former teacher, Hugo Weber, at a party or something. They were looking for a teacher, so he said come and teach visual fundamentals. I said I don’t know how but he just shoved me into the room. And it came automatically; I could teach these things because that was what Moholy believed in. That was a big change in my life. It was when I learned to talk because I had to explain things. I didn’t ever have to do that before. I found I was a good performer and I could explain things very well and I was excited about doing things. I loved looking at students’ work. I was hopeful about every single thing they did. I thought that they would be like me, that they would have a life. They were older than I was. There were only one or two who were my age, because this was an evening class and they were all adults.

Study for sculpture, L’Homme Fatigué_, 1998, pencil and acrylic on paper.

L’Homme Fatigué, January, February 1998, galvanized tin, wire and lead, 11 x 5”. This work was produced at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design while June Leaf was Artist-in-Residence. Photograph: Robert Frank.

Pictures from the period show that you were a beautiful young woman. Did you have much of a sense of yourself then?

Not in a good way. My beauty was like a weapon. I wouldn’t say I enjoyed it, it just made certain things a lot easier for me. I could punish people if I wanted to. I wasn’t very nice you know.

What made you decide to go to Paris?

The first time, I had a girlfriend, Lenore Linder, she was a German girl. She was older, she was 20 and she had been in love with a man who was killed in the war who was from Germany. It took her years to get over it. One day I was having such trouble with my mother because, although every girl now looks like me, none of them did then. You know, blue jeans and long hair and no makeup and all that. And my mother’s favourite gesture when my friends came over would be to pull back the closet door and say, “Look at these clothes.” And my friends who were half spaced out didn’t know what she was talking about. She was really getting after me to change my clothes, but I was doing extremely well in school and I was ready to leave. I didn’t want to continue because I knew that I just had to work hard and that I would one day come back as a visiting artist, which is exactly what happened. I could see there was no point in hanging around. Lenore said to me one day, “I’m going to Germany and to Paris. Do you want to come?” I thought my mother could understand that. I had quit school and I was working at Demets Candy Store on State Street. I came home and said, “I think I’d like to go to Paris.” And my mother went, “Oh Paris, that’s a great idea.” She had this image of her little daughter, wearing a beret and being with artists so that she could tell her friends. She gave me a hundred dollars and I had a hundred dollars, and a hundred dollars went a long way then. So I had money and I went to Paris. Many of the early paintings in the show in Washington were done on that trip, some on the boat, and some when I went to New York City. To be honest, there’s a missing part. It’s probably very critical and it isn’t anything I should be ashamed of, I’m just shy about it. When I had just turned 18 I had an operation and I lost the ability to have children. It wasn’t traumatic for me but it was traumatic for my family; I was too young to know what it meant. It was done too hastily but those were different times. I think I was in sort of a daze and it was horrible. It was the way my family hid it from me, the way they didn’t ever talk to me and nobody told me what it was. I found out later that the only person who was in any way human about it was my father. My sister told me that he asked if I’d still be able to have sexual pleasure. I thought it was so sweet of him to ask that.

Then you went back to Paris again, 10 years later, on a Fulbright?

Yes. That first time I was discovered by this group of people–one was the art critic for the magazine l’Art, one was a poet and the other was an expatriate art historian–and they gave me a beautiful studio. It’s hard to believe but it used to be Picasso’s studio. I did have this sort of fairy-tale experience in Paris which I managed to make into an absolutely humorous disaster. I’m very proud of that because I didn’t feel that they were right, I didn’t feel I was precocious. But I knew that in Paris they liked the idea of precocity. I could see they were all mixed up about everything and I couldn’t work when they gave me that studio. I got very depressed because I felt I was being watched. Something froze up and it took me several years to get that joy back. When I first made these paintings, I used to cry from joy, because I felt it was what I was supposed to do in life. But a darkness crept into me, a self-consciousness. Maybe the trauma of the operation hit me then and perhaps I was afraid of losing my creative fecundity; I say that in retrospect. Then one day I went to the Musee de l’Homme and I saw these beautiful Eskimo engravings on tusks. And I thought, if I could only have something white, something big and white, something shiny like ivory, I could make a beautiful drawing on it. Then I went into my apartment, and I saw this big white bathtub. So I took a large India ink brush, and I painted a child in the bathtub and I cried with joy. I felt I had finally done something. I thought, when they see it they’re going to be so happy, I’ll be everything they thought I was. So these three men came to the door and I said I have something wonderful to show you. I brought them into the bathroom and all their faces went blank. That’s when I smiled inside. “Good, good, I’m going to get rid of them.” They sent me to a psychiatrist, who spoke perfect English; I started talking and he laughed. He said, “There’s nothing wrong with you. You might be a little inhibited about sex but that’s no big deal. Just go home.”

Contact Sheet, acrylic on photograph. Photograph: Sarah Caplan.

So did you get rid of those three guys by coming home?

Yes, but they kept my work and they made me pay them 50 dollars, which was a lot of money then. It was really strange. I’d cry and cry about my work and my father and mother didn’t know what was going on. It was a terrible period. I loved these paintings so much. Finally the work got to a New York warehouse. Then one day my father came into my room and he had them. He had gone on the bus against everyone’s protests. My sister told me that he said, “If she cries like that it must mean something.”

You were pretty emotional when it came to art. Did you actually swoon when you saw your first Cornell boxes?

Oh yes, because they’re very evocative. There’s nothing like them. I can still swoon over art. But Cornell was a breakthrough for me because he was working with the subconscious. I didn’t know there was this strange other part of your mind that you could explore.

**The boxes seem to be whole worlds. You would have responded very positively to that. JL: It had nothing to do with anything special in me. Cornell expands you. He’s just a great, important artist. Especially at that time because he could almost make you smell your dream. That was a thing that nobody had. I just saw a show in Zurich with Max Ernst and de Chirico and it felt the same. These people showed that you could awaken your dream life and bring it to your day life. That’s a great thing to do.

And what did seeing James Ensor’s work do for you?

He was very good for me. Brussels is like Chicago, it has this creepy, industrial middle-class feeling. This brought me in touch with where I grew up; the neighbourhoods, the Jewishness, the ghetto feeling of being cut off from the world, all the merchandise, all the things in the house and the chairs and the bottles and the ugliness of people’s faces. The lack of beauty in their eyes, the lack of beauty in their lives. He makes all that very beautiful. He makes you friends with it.

So the dark passions are what you appreciated in Ensor, not the lighter ones?

He doesn’t have a lot of lighter ones.

But you seem to have more. Is he the beginning of your falling out of the Garden into experience?

Yes, that’s a good way to say it. That’s very nice.

Three stages of developing theme, ‘studio wall’. 1997-1998. Photographs: Sarah Caplan.

It’s interesting how often notions of liberation come up in your work. You talk about yourself as being like a coiled spring in which something builds up until finally it just lets go.

I often wonder about that. That’s an argumentative thing that Jewish people have. It’s like: Prove there is a god. I just don’t believe anything, I have to find out for myself, I have to doubt it and keep poking my nose in it, and all of a sudden I get a whack across the face.

So you keep springing the coil; it’s not something that happens, it’s something you do?

I make something and then I erase it, and then I make it again until it actually comes out and says, “Don’t fuck with me.” Then I say, “Okay.”

As you’re making work is there a constant dialogue between your making self and your observing self?

Yes, because I want to make sure that I am the first audience and that I see what my audience sees. I’m not in love with what I do, I’m not partial to it, I simply am the first audience. Robert always says my favourite phrase is, “That’s the first time that ever happened,” or “I’ll never do that again.” He claims these are my two major phrases. But I do feel that way. I have a friend who says, “You always sound like you’ve just landed on the planet.”

**You’ve said that your sculpture is your anatomy lesson for the painting. Is that still how it operates?

Well, I didn’t think I was going to have the courage to put a figure on the ladder in this piece. I’d given up, I was going to make a sculpture first, but then I put the hair on the woman’s head and then without thinking I took the brush and made it. Because I touched it and then I felt it in my hand.

You literally know through the making?

Well, that’s where my brains are. My brains are right in these hands. They’re very tough now, but I think most people have a wonderful eye that’s on the tip of every finger. Think when you touch someone, someone you love.

When did you start making these wonderful tin sculptures? Is that what you call them?

I think they’re drawings. Somebody bought the first drawing that I made for the sculpture. They’re always made on the same size paper. It’s in black, like Chinese letters. I looked at it and I said, “There’s a mechanical system in this. It’s a great drawing but nobody’s going to know it because nobody knows about drawings anymore. I’m going to make the machine that’s in it.” So I worked for a month and that was the first one. Because when I see a drawing it’s like a locomotive or something powerful into which I just put back the machine.

Studio Wall, 1998, New York. Photograph: Sarah Caplan.

So the visceral kick comes from the mechanics that is its making, which is why you make it in three dimensions?

Yeah, it is like a visceral kick. I’m not always as happy about them as when I make a drawing or a painting because all the ideas come from paintings.

But when you put three-dimensional objects onto the painting surface, as far as you’re concerned, you’re still painting?

I don’t know if they’ll end up that way but when they become three-dimensional, I feel I’ve been defeated.

I wouldn’t think of it as a notion of defeat; it’s rather another way of imagining space.

But space is even more amazing and only a painting can do that.

I want to ask you about a specific piece, Woman as a Gutter Spout. Is it functional?

Yes, the water comes and drips off her foot and down into the gutter.

The ideas for your work seem to come out of the most obvious observations. It’s that simplicity which makes them so profound.

First of all, you don’t invent anything, you just discover the truth. And the truth is always there.

And is the truth always as simple as you make it?

Yeah because I think it’s comforting. In some funny way the truth is reassuring.

You don’t pose a problem to begin with and then set out to solve the problem, which is the way a lot of conceptual artists work. A lot of painters work that way too.

No, I just feel. I’m given the toe and there’s a big body attached to it and I’m supposed to find out what the body is.

Did you have toys when you were a child? Your respect and care for the miniature gesture and the small thing is very pronounced.

No. There was only one thing that I loved besides playing in the playground, and that was dolls. I was in love with dolls. It went on much too late so I used to hide them from my girlfriends. I can still recapture the feeling because I felt so passionate about them. I was always interested in how they were made. I used to take them apart and see how the arms were put on. I remember when I was very small someone gave me a miniature toy grass-cutter which really worked, and when everyone left the room I threw it out the window. We were on the third floor and I got very excited and I thought, tomorrow when I go and play I’m going to pick it up and it’s going to be all broken and I can see how it’s made. I couldn’t wait until the next day. The next day came and it was gone. I was embarrassed about that. I thought I had lost it. It’s funny that no one asked me where it was.

Are you a storyteller in images?

I think my pursuit must be like all poets. There must be some morality operating that eventually gets into a religious dialogue. That heart sculpture in 14 pieces: they were the Stations of the Cross. It amazes me that that just happened, without believing or knowing about it. I had to check that my intuition was good. That’s very interesting to me. I don’t understand except isn’t it what makes poetry? I can’t tell you how happy I was to make the painting Embarking, I didn’t know what the picture was about. If I could re-create for you the feeling I had when it was done and how it was done that would answer a part of your question. I’m going to see if I can, because there would then be a picture and that would help. That was a very hard picture to make and I had to make lots of sculpture, a lot of the boat things are exercises to see if I could get the answer. I also made the musical instrument which actually plays music. It’s a very organic looking thing, like a tortoise shell, and very hard to make. I had to bow it and make layers and cut them down and reshape them and build them up. And then I didn’t want it just to be that woman alone on the end. But that picture was made at the very last, as many of my pictures are made when they’re big. You see, when you make a small drawing you have the whole frame right there to see at once. When you put a figure in you see the rest of the picture. You say, “Oh this can be this small and this can be this big, and it should be this far away.” You see it right in front of you. When you make a picture that’s big, you work it and work it and you put in something and you fall in love with it, then you stand back and say, “Oh dear, that’s too big,” and by the time you build it up and get layers, you’re fagged out because you’ve been over the thing a hundred times and you’ve forgotten what it is.

Centaur Warrior, 1997-1998, painted photograph. Photograph: Robert Frank.

Centaur Warrior, 1997, galvanized tin with lead silver spider, 10 x 6 1/2”. Photograph: Robert Frank.

So do you give it up?

If it’s gone like that, which happens occasionally, I think I’ve got one last try because where I’ve been with this picture is wonderful but there’s nothing left. So I simply close my eyes and make it. Not completely closed. My eyes are closed because I have remembered it so it’s just a question of putting the lines down. I remember I stood back and the boat just went klunk, it just sat right there, sticking out of the picture a little, which is what I wanted. I wanted it to be as though I had put it in the picture and I thought, there it is, it weighs a ton. Nobody knows, nobody cares, but I know it’s there. Then I said, “Let’s put some people in it.” And I painted a woman I’d seen walking down the street; I put a man fixing the strings; I put in somebody waiting and then I said, “We’ll have a mom with a child, just silhouettes.” I placed them in the boat, just like that. And somebody tying the ends of the strings, which go all the way across the boat. The figure on the prow, which you may not see in the painting unless you study it a long time, is actually a woman. Then it named itself; it said “Embarking.” It was worth the whole year. And I thought is it going or is it coming? Is it the end of something or is it the beginning of something? It doesn’t matter, I don’t even care what the picture looks like, it just gave me an insight into a voyage. I went through a great struggle and I don’t even understand it. I don’t even know why I’m being rewarded with these works. But when you stand back from that painting, and you go way across the room, there’s that boat just sitting there on its side the way boats sit on their side. I was talking about things that lift me in my life like Watteau and Masaccio. In fact, A Pilgrimage to Cythera is very much like this boat thing. Except in the Watteau they are coming back from a love fest or going to a love fest, or they’re going to be slaughtered or they’re going to be happy. It’s some kind of moment. Do you know about the historian who wrote four volumes after seeing a Poussin painting called Dance to the Music of Time. It didn’t surprise me at all that you could write four volumes after looking at this painting. When you look at Poussin you realize he’s just as much a carpenter as he is a painter. Everything in there has such weight, it’s like a building. It’s put in there like it’s granite. Well, that’s the way I felt when I made Embarking. And I’ve tried to do that painting again and again and I think to myself, now I can make the painting because I understand it. But the myth only visits me once, and then I have to go get another one. I could perfect it, I know it so well. But it just won’t come, it won’t work. I have to be on another search.

You also referred to coming to Nova Scotia and creating a mythology. What’s fascinating about it is that the stories tell you into belonging. You do this all the time.

I know. I don’t want to accept everything and make a myth out of it. Having that kind of acceptance is a habit of mind. And lately I’ve been thinking that maybe I should forget about the painting, figure out what I don’t approve of and make a stand.

What was it that provoked you to make art in the first place?

I must have been about 15 when I finally decided. I really didn’t know what painting was. I always thought that drawings in comic trips were magic. I thought anything that talked to me from the page was art, but I didn’t know anything about art. I didn’t have books, I didn’t know anything. My grandmother lived with us and she died. She had a room in the back. She visited her three daughters, my mother being the middle one, and then every three months she would go to a different daughter. So she lived with us but she diminished a lot in her last years. Then her room was empty. So I thought that’s the room where I will start to paint and I bought a little box of oil paints and two canvas boards. I remember them so clearly: one had a pebble surface. I have them still. I walked in there and I remember I put the brush down on the canvas. Not the board but the canvas and I heard a little sound like a drum tap. And I painted this woman face down, rump up, asleep on the bed. It was as if she was on a cot in prison and I remember I put a crack on the wall and the crack accidentally went into her behind. So I scratched it out because I was self-conscious. That was my first painting. But I remember it just went “tap” and then out flowed this language. Then I made a second painting, again without any knowledge. The second one was of a woman picking her toenails on a bear rug. I worked a long time on the ferocious head of the bear. She was naked and sitting on it. I remember I just said, “Now I begin.” But that was without knowledge.

What interests me is the casual way you made images back then. You make the connection yourself in saying that there’s still that quality in your work.

I know, I don’t understand. I have this dear friend and every now and then in one of our conversations she’ll say, “You live in your unconscious, you have complete contact with your unconscious.” I don’t know if that’s the answer, but it’s the trait of a painter.

So you never said to yourself that art had to be something big and grand and heroic. It was the very casualness of what you were able to paint that’s remarkable and consistent.

Art was over there, it was big and strong and heroic. And then there was an activity I was meant to do which didn’t measure up to my image of what art was. But I just waited, it was like somebody whose mouth had been taped till they were 15, and then off comes the tape.

The speaking has been consistent since then, hasn’t it?

Yes, exactly. When you think about it, it’s amazing that I could keep the tape on so long.

This is a bigger question and I’m not sure how to ask it. How do you learn more, or do you already know everything and it’s just a question of getting it out from the subconscious?

Well, every day it says to me, you don’t know how to do such and such. In other words everything–the people, the images, the vision–is waiting there behind the door. Then they say, “Hey, kid, we can’t come out. You don’t have a floor.” I say, “I don’t know how to make a floor,” and I don’t hear a word from them.

So, on the female centaur that right hand which you’ve now figured out had to do with working out the practical problem of how a hand functions?

I’ve got to make it so that you see the centre of her palm. It has to be cupped because that’s how hands are. So she could unbutton her dress, she could put on an earring, or she could stab herself in her neck if she wants. But I’ve got to get that hand ready to do something. It’s so tiny, how am I ever going to do that. I thought, I’ll do paper, and then something said, “Paper won’t do.” “Okay, tin?” and there was no answer. So I say, “I have these tiny drills,” and my most excitement was the drill bit was too small for the machine, so I wrapped paper around it and made it thicker so I could fit it inside.

June Leaf wearing wings from Angel on Treadle, 1980-1990, New York studio, December 1997. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

Do you talk to yourself when you’re in the studio?

I’m told that I do shout and talk every now and then, but that’s because I don’t think anyone’s home. But I don’t see any reason not to. A friend whose portrait I painted told me that what I say is, “From this to this, from this to this.”

The mechanics is profoundly important to you isn’t it? Do you worry about that?

Worry is very important to me. Oh, the worry is heaven. I don’t know why. I have an image of this scene in Short-Timers, that beautiful book that was made into the film Full Metal Jacket. The medics have to go out and get the wounded, and the description of the medic carrying the bodies back from the battlefield is just how I feel when I paint. Leon Golub is the same. I say, “Leon, we’re two medics you know. Just to hold them and lift them and touch them and fix them and know them and bury them and resurrect them and kill them.”

But Golub is taking his painting into the territory of politics and that’s territory into which you don’t venture.

I know. That’s what he says. His father was a doctor. I feel I could have been a doctor, I could have been a surgeon. It’s the same thing, it’s like “this to this, this to this.” And sometimes when I open up the body I say, well why don’t you look under this organ just to see what it’s like, even though it’s messing up your piece. But I do that all the time. I break things. Like the grass-cutter which I threw out the window. It’s like, you love it so much, you just want to throw it into the air.

So what could be read as violence in your work is not an impulse to destroy; it’s to know more about it.

It’s to celebrate its appearance. It’s to applaud it but it turns out you wreck things when you do that. I’m more careful now. I have a big problem with this.

Are you talking about personal relationships or just art?

Oh, well, I’m pretty well-behaved.

You want to make sure that these things continue to have life. I don’t know that I know an artist who makes such living things.

It goes like this. A friend of mine has two of my pieces and she said, “Your pieces are so strong, they never break. When you drop them on the floor they just bounce.” Well, that’s how I make them. I make them so that they look fragile. When they fall, I think of it as a test. If it breaks, I fix it so that it’s stronger. I like them to fall off the walls, actually. This is a friend. She posed. I love the back, the neck of this woman and her shoulder blades and I love this profile. It’s the reverence for the body that I want to have in my work.

I remember you said in Mabou that the two most beautiful things in the world were a woman lifting her hair away from her neck, and the rear end of a horse.

And putting on an earring, or buttoning the last button at the back of her dress.

Do you mean that those gestures feel as good for a woman to do as they are for a man to see?

What they are is the fastening-down of her determination.

You like the strength of women then? If the male audience likes that gesture, it’s not about the male gaze, it’s about appreciating the strength of women.

It is about strength. Real beauty is any emphatic thing that we do. It’s like all the most powerful things in nature, things that are just in us. They’re our best moves, aren’t they?♦