The Worth of Living and Loving

An Interview with Marlene Dumas

A small new painting by Marlene Dumas in the first room of her recent exhibition “Myths & Mortals” at David Zwirner in New York seemed, by dint of its strange force, to pull all attention to itself. Kissed is read first as an abstraction—a mix of light and dark—and then, in the way that you do as a viewer trying to make sense of a complex image by tilting your head left and then right, advancing and pulling back, you begin to pick out the subject. Two people, heads closely cropped inside the canvas frame—the angle suggesting they are prone—are kissing, so deeply kissing as to confuse which lips are where, even though one figure is in white, the face largely shadowed by blue as if the blood that suffused the cheeks were returning to the heart emptied of oxygen (a myth of circulatory exchange), and the other figure in brown, with a very ruddied tone. The disorientation we experience is precisely what Marlene Dumas wants, saying that’s what a good painting should do. In writing for the catalogue that accompanied her exhibition “Name No Names” at the Centre Pompidou in 2001, she used a quotation by the French Symbolist poet Paul Valéry—“To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees”—to support her understanding that the fixity of naming could be abandoned in love and in art. In love and art, confusion and disorientation can be generatively liberating, a tabula rasa of possibilities, and she added, “Why do I draw? To remember or to forget?,” the confusion of forgetting making it possible to see something anew.

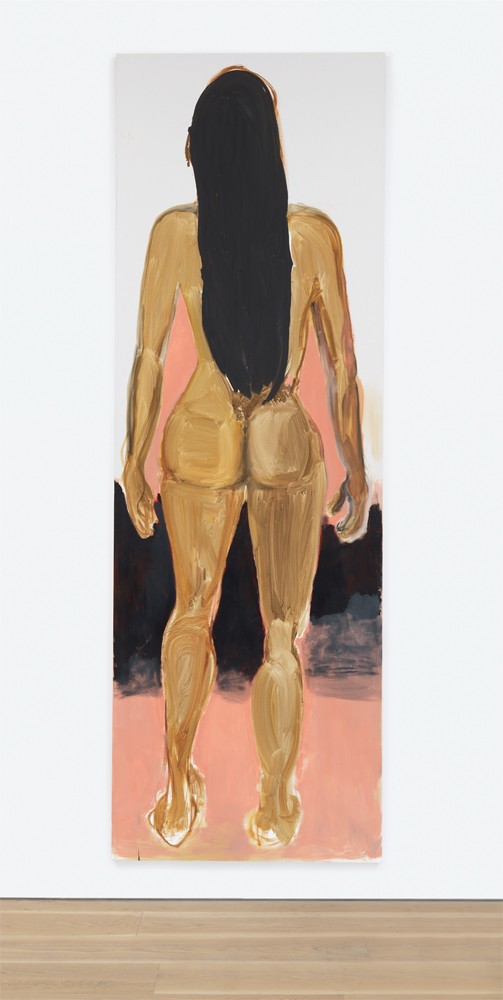

Marlene Dumas, Amazon, 2016, oil on canvas, 300 x 100 cm. Images courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong.

That small painting, Kissed, addressed the issue raised in Dumas’s works in “Venus & Adonis,” in particular, of depicting the interaction between two figures. These works, created for the recent Dutch translation by Hafid Bouazza of Shakespeare’s long poem Venus and Adonis, were exhibited in “Myths & Mortals,” and the subject of many was the relationship between two figures, the goddess Venus and the beautiful adolescent boy Adonis. Dumas tells us that when presented with a single figure, the viewer becomes the second of the pair—the viewer as lover. If the viewer is looking at a painting of two figures, say, Kissing, does the viewer become voyeur, watching from the outside? The risk, Dumas pointed out, is that the work could become a point of illustration rather than engagement. And with two figures there is also the question of power. As she says, the “struggle with who’s in power, who’s on top and who is next to whom”?

This, in part, is the substantial question with which she has grappled from her earliest work and which she has also addressed in her extensive body of texts. With tongue partially inserted in cheek, Marlene Dumas wrote “Women and Painting” in 1993, a seven-segment series of aphoristic statements, published first in Parkett (no 37) and then included in The Image as Burden, to accompany an exhibition of the same name, with an annotation in 2014 by Dumas, stating that “Women and Painting” had been written as a light-hearted response to the question male artists never get asked: “How does it feel to be a woman who paints?” It hadn’t been intended as a scurrilous charge against males and male painters, is what the 2014 notation implied, but in fact, the seven sections aren’t about men at all; they are about her understanding of what painting is and the resolution of the issues around that subject, which are essential to her. Each begins with a deliberately provocative statement and proceeds to beautifully and effectively argue the topic of painting. One begins with the opening statement, “I paint because I am a dirty woman,” and goes on to say that paint can never be a pure conceptual medium: “The cleaner the art the more the head can be separated from the body, and the more the labor can be done by others,” or, in another section, “I paint because I like to be bought and sold,” followed by her explaining that painting is about the trace of the human touch, about the skin of a surface and that the content can’t be separated from the way the surface feels.

There’s a consistency in Dumas’s pressing and focused attention to what she is doing, which is painting, to the tension or the productive conflict between what it is she is painting, that is, to the subject, and what it is she is doing, which is painting—what she refers to as the “matter.” In the foreword to The Image as Burden, the curators quote Dumas’s asserting this distinction, and then the coming together: “There is the image you start with and the image you end up with, and they are not the same. I wanted to give more attention to what the painting does to the image, not only to what the image does to the painting.”

Venus insists, 2015–16, ink wash and metallic acrylic on paper, 30.2 x 23.5 cm.

In “Myths & Mortals” the works move from the small, Kissed at 11 7/8 by 15 3/4 inches, to larger than life size in Amazon at 118 1/8 by 39 3/8 inches. Dumas’s sources are everything her magpie eye encompasses—magazine images, newspapers, the work of other artists, films, advertising—but with Amazon, I have one of my own, responding with a frisson of familiarity and pleasure to a painted gesture that was clearly intentional. Everything is considered even as it is happening. The figure Amazon is monumental; her black hair is a spill from almost the canvas’s top edge to very nearly the midpoint of its length and ending just below the figure’s waist. The weight of this lush cascade has it falling straight as a plumb with the exception of one thick tendril, which curls lower, reaching toward the divide of her warrior-fit ass in a sensual gesture, recalling to my visual memory John Berger’s essay on Caravaggio in And our faces, my heart, brief as photos (Pantheon Books, New York, 1984), where “almost every act of touching which Caravaggio painted has a sexual charge.” Berger describes the painting of a young boy as Cupid and writes that “the feather of one of the boy’s wing tips touches his own upper thigh with a lover’s precision.” In Dumas’s Amazon this curl is not an accident but a moment of auto-eroticism presenting well the issue of a single painted figure and the response of the viewer as the second in a sensual exchange between painting and looking.

Pleasure as a response and impetus is further evidenced in the “Venus & Adonis” drawings, and beauty, too, both in abundance in Dumas’s work. Beauty’s bad rap is addressed by Wendy Steiner, writing in the “Burden of the Image” about the burden beauty is—and most often the image is a woman—and she writes about the discomfort and ambivalence generally felt about beauty “both within and outside art.” She says, “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with the compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish.” Exactly, and we are again with Paul Valéry and Dumas, and the power of forgetting (oneself) and losing control and the lift and transport of the transformative act of painting in this state, and for viewers, too, although with both feet on the ground.

Venus in bliss, 2015–16, ink wash and metallic acrylic on paper, 26 x 22.9 cm.

Two small drawings bring the pink blush of blood to the surface, with pleasure being the intention. In Venus praises the pleasures of love she is enraptured. Colour suffuses her face, and her head is tilted back, eyes closed, lips parted in anticipation and desire. Her ecstatic face and pinkened neck fill the frame. In Adonis blushes blood has been brought to his face because he has been made aware of pleasure through the erotic lines spoken to him by Venus. It is hers, this sensation and desire, not his, and he blushes because he is uneasy. In his modesty and reticence, he drops his head and lowers his eyes to avoid the heat to which he can’t respond. Both Adonis and Venus are beautiful, but their beauty holds no power for either. In the end, as the poem unfolds, the power belongs to the indifferent, grinning, wild Boar. These two small drawings are ink washes and metallic acrylic on paper. The lightly reflecting surfaces shimmer with desire— ours as viewers and theirs for their particular passions, which don’t intersect. In this recent work—paintings from small to monumental, and drawings to illustrate Shakespeare’s erotic poem, which presents Venus and Adonis and their own palpable heat—Marlene Dumas has created a small populous: the works themselves and we the viewers, together, engaged with her in acknowledging painting as a positive act of making, and in that recognition the affirmation that, as she says, “you look at it to feel that it is worth living and worth loving.”

This interview was conducted by telephone with the artist in her Amsterdam studio on July 25th, 2018.

Marlene Dumas: I was happy with “Myths & Mortals” because it had a different kind of energy. When I exhibited “Against the Wall” in 2010, I was trying to work too thematically and it was draining and difficult to do. But this exhibition was the opposite, a bit of “raging against the dying of the light.” It was an attempt to concentrate on the living and the erotic aspects more than on death and the horrible aspects, even though they are connected. In that sense it was a much more positive project to work on.

Border Crossings: It’s interesting that you quote Dylan Thomas because poetry seems to be of interest to you. For your research on the Venus & Adonis book project, you read both Shakespeare’s version of the story as well as Ovid’s in the Metamorphoses.

Venus praises the pleasures of love, 2015–16, ink wash, metallic acrylic and pastel on paper, 23.5 x 20.3 cm.

I have to admit that it has been very enriching for me. I knew the work of Hafid Bouazza, the translator, but I never knew him personally. I am a bit older and somehow we never managed to meet, but I still have the email that he wrote to me in May of 2015. He said that next April—that would be in 2016—will be the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death and he had translated Venus and Adonis, which he had always wanted to do because it is one of the most erotic poems ever written. At the beginning he asked me to do only two drawings. He said, I know you’re very busy but maybe you would like to illustrate the poem through two of the high points. He said that in Shakespeare the sexual and the violent acts go together, and I didn’t know quite what he meant because I didn’t know the poem. But I thought, “How can I not take on this challenge of working with what I’m being told is Shakespeare’s most erotic poem?” It was also a period of my life where friends close to me were seriously ill and that made it more of a challenge. Then when I started to read the poem, I realized how long and difficult it was. I couldn’t get into it right away and when I mentioned the problem I was having, Hafid said, “When you look at a painting you don’t just look at it for three minutes, you also take your time.” So I realized I was being a bit too quick. I read it for the first time in his Dutch translation and I went through it quickly to see what type of things Shakespeare was referring to, and one of the first images that struck me is where he described her eyes when she was upset as if they were the tentacles of a snail that went back, “into the deep dark cabins of her head.” So the first image was the snail. I emailed Hafid and said, in a childlike way, “Did they have snails in Shakespeare’s time?” I had never worked with mythology and I was always a bit wary of artists who did because I wanted my work to be of this time and not be a nostalgic look at the past. So it wasn’t a question of saying, yes, I know this poem and I’m going to do it. I found it quite difficult in the beginning and as I read it, more problems came up. I didn’t realize how young Adonis was and there was the element of Venus being a goddess and so beautiful. She is older and more experienced and she’s had Mars and all these other guys, and Adonis is just starting to get a beard. He is still a virgin.

That’s right. He does say to her, “Fair Queen, measure my strangeness with my unripe years,” and then he implores her, “Don’t get to know me before I know myself.”

Yes, the poem has beautiful lines but I didn’t see that the first time. I had to go step by step and since Hafid had given me total freedom to do whatever I wanted, I started to ask questions on my own. In Ovid’s version there is the swan and I assumed it was also in Shakespeare. I always work in a fragmentary way and I started to look at all the classical paintings depicting the story and you would often see swans. So I had done my swan before I realized it wasn’t in Shakespeare. Sometimes Venus’s carriage is drawn by swans and sometimes by doves but then the dove added another problem. How can you think about painting a dove when Picasso has made it his own? I had wanted to stick to Shakespeare because I realized there were a lot of problems in going back and forth between him and Ovid. Then I started to read about the gods and the goddesses and got totally mixed up trying to figure out who did what with whom and when and that one’s mother was that one’s brother.

As you went through Shakespeare’s poem, did the language suggest images other than the swan? How did you finally figure out what the relationship between Venus and Adonis was going to be?

The most difficult thing is understanding concepts and ideas and then physically making something out of that understanding. At first I thought Adonis wanted Venus but then I recognized that he was resisting her most of the time. He is attracted but then he frowns. The emotions are fantastic and constantly changing. It was only in rereading the poem that I understood how she moves from being coy to being quite harsh and insistent. I was worried that my portrayal and presentation of her was too simplified. She wasn’t just a pin-up. In a lot of the old paintings she was this blonde, luscious goddess, but because I wanted her to be read in our time, I found it difficult deciding what type of woman I was going to use. In the illustrations sometimes she looks childish; sometimes she looks darker or lighter. She is not just one type. But the most difficult problem was getting the interaction between the two. In the beginning there were a lot of drawings and they were made very quickly because I work gesturally. But I did reject a lot of them because they looked kitschy. Depicting a man and a woman trying to kiss one another is actually very difficult.

You reprise the composition from Hierarchy, a small painting from 1992, in three of the drawings in Venus & Adonis. You duplicate it in Venus pleads, Venus insists and Venus forces.

Eye, 2018, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm.

Yes, although the source for Venus forces was the beach scene from From Here to Eternity. Hierarchy was inspired by the Japanese film The Empire of the Sense and this was part of the misunderstanding with “Myths & Mortals.” New Yorkers who don’t know my work said it was as if I suddenly decided to take on a love story and that I had never done it before. This is not true. I have always struggled with how you make an erotic painting or how you treat the interaction between two figures because most of my figures are alone. When you have a solitary figure, then the viewer is actually the second person or the lover. But if you portray two people kissing, then you have the problem of illustration and how do you solve that without making a very kitschy painting. That aspect has bothered me and it comes back in different forms every now and then. Bouazza said that in my first Venus & Adonis drawings, the woman was posing a bit and could I change that. He asked if there could be more pleasure. I realized that I often work with people posing; you have that in porn as well as in the pose of the stripper and the seducer. So I thought maybe I should give Venus more pleasure. The pleasure/pain experience does go back and forth, and that is something I have been busy dealing with for years. If you want to deal with love stories and if you want to deal with interactions between figures, you have to struggle with who’s in power, who’s on top and who’s next to whom.

Venus in bliss is an image that comes at a point in the story where Venus’s amorous intentions have met with some success. The effectiveness of the drawing has something to do with the blush on her cheek but also with the way you cut the drawing at the nipple and above the eyes. The cropping made me think of Rodin and his framing of the Cambodian dancers and his nudes. Because he was looking at the models rather than the paper, the image runs off the page. How careful was the composition of Venus in bliss?

Venus in bliss is one of my favourite drawings and it was very deliberately structured. Your question reminds me that in the criticism of my work, Luc Tuymans and I are often compared. One critic said if Luc is undercooled, then I am overheated. But the same critic also said that one of my paintings was underthought and that I objected to. In the end I am never underthought. So with Venus in bliss I was very aware of how I was composing the image. I cut the head off at the top and I wanted the dark patch of the underarm and the nipple to be erogenous. By the way, it’s wonderful if you can do it without thinking and let the material take over. And there are drawings where you have thought about it many times and it still doesn’t work.

…to continue reading the interview with Marlene Dumas, order a copy of Issue #147 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!