The Thread of Painting

An Interview with Ghada Amer

There’s something about thread that’s as effective in reducing male assertions as Delilah’s scissors were on Samson’s hair. I think of British artist Anna Hunt who rendered iconic modernist architecture in six-by-eight inch satin-stitch embroideries, and here we’re looking at the work of Ghada Amer, who graduated in 1989 with a MFA in painting from a well-regarded school in Nice leaving with conflicted messages about the efficacy of a woman painting at all. Art history told her gestural, heroic-scale abstract expressionist works were the purview of men. Paint was theirs. So, her medium–her paint–she decided would be thread. She told Border Crossings, “I didn’t invent embroidery, but I wanted to paint with embroidery. I was speaking about women with a medium for women, and it made the speaking stronger and more present.”

The earliest pieces were simple, single line drawings–silhouettes in red thread of women doing domestic daily tasks. Ironing in La femme qui repasse, 1992, or Cinq femmes au travail, 1991, where women are shopping for groceries, caring for children, cleaning, cooking.

Ghada Amer and Reza Farkhondeh, Girlscape, 2008, monotype, steel matrix painting and linocut on Rives BFK and Kozo-shi papers, 34.75 x 44.75”. © Reza Farkhondeh/Ghada Amer. Courtesy Pace Prints.

The subject quickly shifted; it was still women but now the imagery was derived from American soft-core porn magazines. White women alone and together, in acrylic and embroidery on canvas, the same figures often repeated in bands or clusters, stitched in thread with the tailings gathered in knots or drawn in bundles, obscuring the figures or connecting them like lines of communication, extending the colour gesture across the surface. Paintings like The Big Blue Expressionist Painting, 1999-2000, Red Drips–coulures rouges, 1999, Black Series–coulures noires, 2000, or Untitled (New Grid), 2000, their titles alone indicating the sources Amer was challenging. She said, “I had to have lots of thread so that I could drip, because the threads are my drips. That’s my Pollock.” Robert Motherwell or Barnett Newman with their dense black blocks of pigment or Sol LeWitt in the grid superimposed on the playfully erotic chorus line of women–all are conjured in these pieces. Amer identified the challenge and the gaps she noted in the history of painting and answered them.

Since they were students in France in the late 1980s, Ghada Amer and Reza Farkhondeh have been friends, confidants and, as early as 2000, collaborators. While the collaboration was recognized by others only in 2003, it began with Farkhondeh surprising Amer by painting on one of her canvases while she was away travelling. She liked his contributions to her work and it continued, first as a game and then by serious and mutual agreement. Identified as rfga after the title, they were introduced to audiences almost by stealth, sounding, as Amer puts it, like a military operation. The newest work, drawings and prints, are worked in turn until the piece is declared complete.

Camouflage Girl-A, 2008, a monotype in woodblock, inkjet and digital sewing on Japanese papers and linen is one such work. A young woman stands against a ground of leaves silhouetted in pink, their stems or drips of paint forming a vertical, muted frieze, like printed fabric or wallpaper, although there appear to be no repeats. Very much in the foreground, in spite of having her form somewhat obscured by loosely painted leaves in military green, the young woman is at once assertive in her provocative pose and reticent in her sideways glance. A close-fitting camisole is pulled down from her shoulders revealing her breasts. She and the details that make up her image are stitched in dark thread, confusing in their trailing off, a loose reference either to bondage or to a careless insouciance in coming “undone.” Unlike most of the earlier work where the figures and their pleasure or provocations are obscured by skeins of thread or images overlaid one on the other, or painted over in washes of colour, the subject in Camouflage Girl-A is alone and unveiled.

It’s not possible to look at Amer’s work without thinking of veiling and layering, obscuring and revealing, of the languor implied in the time necessary for images to be apprehended. There’s other layering as well—the layering of painting traditions where Amer has sampled the history of 20th-century American painting and put it to her own use; the layering of the traditions of needlework, tapestries, carpet weaving, the use of patterning and repetition in the density of the surface imagery, almost cloisonné in its richness; and the layering of cultures—East and West, current and past.

Layers and veils imply a space between and it may be here that Ghada Amer finds herself most at home. We asked her if the idea of being “in between” had influenced her art and she replied, “Yes, because I don’t feel myself only French of Egyptian or American…. It’s not a feeling of being in exile because when you’re in that state you know you’re exiled from something. The problem for me is that I don’t know what I’m exiled from.” New York is where she belongs, she says, because it’s an international city and, therefore, home. That city, and the work she makes in pursuit of an ideal.

Ghada Amer, The woman who failed to be Shehrazade, 2008, acrylic, embroidery and gel medium on canvas, 62 x 68”. © Ghada Amer. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

A painting from 2008, The woman who failed to be Shehrazade, is the mix of layers and veils and cultures that is East and West. Predominantly worked in greys, the painting is a large canvas flanked by two mirror-image women. Naked, elbows bent and arms raised behind their head they are, at one time, Shehrazade-exotic and derived from Western porn. Faint images of other women, also paired, ride over the primary images like shadows on a curtain: Ingre’s La Grande Odalisque, Manet’s Olympia, the open/close shutter of Warhol’s serial repetitions, and a smokiness that is voluptuous in the sense of ease, fullness, security and bodies replete. This work is intimate. Much of Amer’s work is. Intimate, she agrees, and also about longing. The impetus for the work grows from this longing, which can never be satisfied. She tells us, in a tone of understanding and maybe resignation and acceptance—this is the nature of the human being.

The interview with Ghada Amer was conducted in her studio in Harlem in February 2009. Ghada Amer’s work will be exhibited in Istanbul, Cape Town and the Moscow Biennale in the fall of 2009.

Border Crossings: What was it like to grow up in Egypt?

Ghada Amer: I lived in Cairo until 1974, but because my father was a diplomat, we often travelled to Morocco and to Libya. So I grew up in North Africa basically, never in one country. What was it like? I have horrible memories of the war with Israel because the years I was in Cairo coincided with the wars in ’67 and ’73. The memories of the planes and how we had to hide stick with you when you experience them as a child. It was better when I went to Morocco because there was no war.

Did it seem like an exotic life?

Yes, because I was one of the first kids to travel. Back in 1963 not a lot of people had that opportunity. The general population was not allowed to travel until Sadat came to power, and only very special people were permitted to go outside the country. As a member of the diplomatic community, my father was considered one of those special people. We travelled with him, and then he went on his own as a diplomatic courier. He would bring back things from all around the world, and it seemed as if we were open to the world.

Was art part of your experience as you grew up?

Not at all. I think I chose art because my father is a big reader and he knows about everything. In a way that annoyed me because he would say, “You don’t know the capital of this country” or “you don’t know what happened in this year during the French Revolution.” The only area where my father did not know anything was art. Except for mine, he doesn’t like art.

Was there a prohibition inside the culture about the making of images?

Maybe now, but there wasn’t a prohibition then. The body and nudity is certainly prohibited, and there are people who don’t want things to be realistic. The problem is with any realistic depiction of the human body because then you’re assuming the role of god. You are trying to imitate creation, which is an interesting concept. So that is forbidden. Which is why sometimes in the miniatures they put a line through the image, which lets you know that it is just a representation, it has no life. How do you represent the prophet in the cinema in historical movies, because the prophet cannot be represented at all? What they do is make a void.

Do you think that making art was a way of escaping your father’s influence and his formidable knowledge?

I think so. But it came much later and it was a little bit subconscious. I was drawn to art as a child, and if there is an artist in the family it would be my mom. She liked to sew, and she was a coquette and wanted to have very nice clothing, which was very expensive to buy at the time, so she had to make them herself. We were four girls and she wanted us to look nice. My mom is a very fine engineer with a PhD and a career, but in the afternoon she would sew. My grandmother sewed at home, of course, and because she was a peasant, she would mend stuff. I would go with them to the garment district where they would choose patterns and material. All this was part of my growing up. But there wasn’t much cooking; cooking was not as important as sewing and making decorations.

Did you learn sewing techniques by watching?

My technique with the thread I taught myself, but the patterning I learned from her. She would say, “If you want a dress you have to help me,” so we became her assistants.

Your three sisters as well?

I am the best. They are horrible at it and I don’t know why. I would come home and one of them would say, “Can you do this for me?”, and my reaction was, “I thought we all learned to do this together.”

Did you realize early on that this way of making yourselves look elegant could also be a way of making art?

Never. Because making art came much later.

I read somewhere where you said that as a teenager art saved your life. That’s quite a dramatic recognition.

I was advanced in my schooling and, as a result, I finished high school when I was 16. I don’t think I was ready to go to university. As a child I always drew and I loved it. I was only allowed to draw when I finished my homework, so it was an incentive to finish quickly. When I was 16 it was a very bad time for me. I got my diploma but I was depressed, and it reached the stage where I couldn’t get out of bed. It was very, very severe, and the only thing I could do was to draw. It was the only thing that I could concentrate on and the only thing that could calm me down. My parents wanted me to study medicine so I could become a doctor and I hated the idea. I did like math, though, so I decided to study it; but I couldn’t follow and that was my first failure. It was very important to my parents that we be good in school, and there was a lot of pressure on me, so when I didn’t do well I got even more depressed. I couldn’t do anything. I would go to the university, but I would cry all day and then come home. It was terrible. Then I was told there was something called Art School. I asked what that was because I didn’t really know anything about it. I took the exam and failed, and then believe it or not, I took the exam on sewing. I did sewing, but it was landscape patchwork. Even though I had experienced another failure, there was something about this thing called Art School that was appealing to me. I had to do something, so I went to university to study English and German. My father was the Ambassador in Algeria at the time. I eventually studied art in Nice, and by chance it turned out to be a very good school.

What was the nature of the work you were doing when you came out of art school?

I’ve always done the same work. It was about love and about women, but they were not sexual.

What gave you the permission to use subject matter that came out of porn? How did you finally make the break?

I was so frustrated that I couldn’t speak about this to my parents. I couldn’t rebel, so in some way it was my own rebellion because I knew that my not being able to speak was wrong. I finally said, “I don’t care, they may punish me, but I’m doing art.” It came to the point where I would either leave home, not talk to my parents, or get involved with a non-Muslim guy. Or, I would speak about it. For me this was more permissive than if I really did it. Maybe it wasn’t very courageous, but I couldn’t transgress in real life; I could only transgress in my painting.

Ghada Amer and Reza Farkhondeh, Aqua Kiss, 2008, monotype, pressure relief, steel matrix painting and spitbite on Hahnemuhle Copperplate, Misu Usokuchi and Mulberry papers, 28.25 x 38”. © Reza Farkhondeh/Ghada Amer. Courtesy Pace Prints.

De Kooning said that oil paint was invented to paint flesh. It makes me wonder why thread was invented? You change the medium and raise the question of the quest for beauty. Is your work beautiful because of its material or because of the way you treat the material?

It is very important to me that the work should be beautiful. Otherwise, why would I do art? It’s through beauty that you think. It’s like music; if it’s horrible music you don’t want to listen to it. It may be interesting but it’s not beautiful. I used serial images because it was my only way to be able to paint with thread. This in my explanation of why I had to repeat many things, like the Arabic motif. I had to have lots of thread so that I could drip, because the threads are my drips. That’s my Pollock.

When we look at the paintings, they are sensual, sexual and a turn-on. Are they for you to make?

Yes, but it’s not every day I can make a painting. I have to be in the mood to be sexual and sensual. I might work with my drawing, and it’s the beginning that is more sensual. Then I have to work it so much that it becomes very distant. It is very important to go from the porn magazine to the first drawing and then to the third drawing, because if it is not done with a little bit of sensuality, then it doesn’t work. But often the making of it is such a laborious process that it kills all the desire.

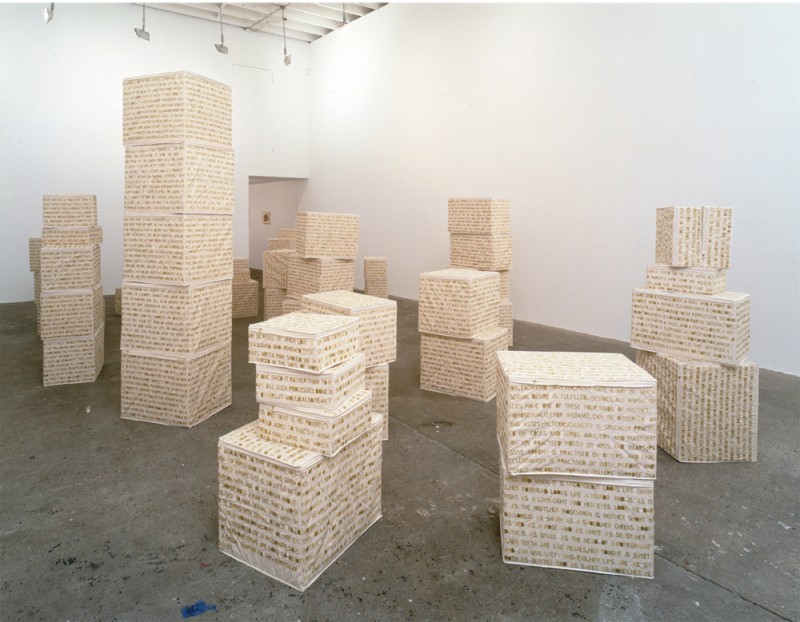

Encyclopedia of Pleasure, 2001, embroidered sculpture, dimensions variable. Installation view at Deitch Projects. Courtesy Deitch Projects, New York. © Ghada Amer. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

How did the collaboration with Reza first come about?

I have collaborated with him since 2000 under the label RFGA. As I said, Reza and I moved together, we have always had studios near one another, and we are very good friends. Then he got depressed, and it was an even more serious depression than mine. Because it flashed back to my own depression, it really freaked me out. It turned out that the only place he could go was here, and he slept in this room. He stopped eating and he was letting himself die, and I was obviously very concerned. I didn’t know what to do, and then a friend of mine gave me William Styron’s book about depression called Darkness Visible. I gave it to Reza, and he decided to go to the doctor and get some medication. But he had stopped painting completely for two years; he felt it was because of his painting that he had become depressed. Then when I was travelling he came into the studio and painted on my painting.

You were okay with this?

In the beginning I was surprised that he could paint. But I looked at it and thought, “This is not so bad.” He told me, “I think your backgrounds are boring.” I said, “You’re right,” and so it started like a game. He had nothing to do. I would sew, I would go out, and he would paint. We were having fun in the studio doing this kind of work. Then after one or two years I saw that my work had gone in a new and very interesting direction, so I said, “We are collaborating,” and he said, “No, this is not actually me.” I said, “I think you should sign them,” and he said, “I don’t want to.” But when I decided to make a show, I told him I was going to put in the title RFGA as if it were a secret military operation. No one has ever asked what it meant. Then in 2003 I started to tell my galleries, and while they were very interested, they found it a little strange because they were concerned about my market. We also got much better at doing this. Then in 2005 we decided to do drawings and prints because nobody cares about them market-wise. But we started to make money and that really freaked out my dealers. So we went to Singapore and we decided to experiment. He would do something on the paper and give it to me, and I would do something and give it back. We continued in this way until we both agreed it was finished. And we signed them together with both names, not under the RFGA label.

What is the source of the comic book and fairy-tale characters? They are essentially figures of innocence.

It is all of the things you are told when you are young. Things that are not true: like if you behave the prince will come. For me all the moral issues go through the important feminine and masculine figures in our society, and I don’t think that’s very different from sexuality, which also raises moral issues. I mean look at Snow White: a woman who lives with seven dwarfs.

So when we see Snow White having a good time with any number of her little close friends, do you think of that work as transgressive?

I don’t know, because when I did it I really believed in it. I have known Snow White for a long time. I grew up with all those stories. I read them in Arabic: Little Red Riding Hood, Sinbad and Ali Baba.

The fabulous thing about Snow White is that she reverses the harem structure: she’s a chick with seven guys.

Absolutely. I never thought about her that way. But more important than any other thing about her was that she was white.

Do you think that your comfort with women comes from your cultural familiarity with the notion of the harem?

Yes, because we are brought up as women together. It’s not necessarily sexual, but it is comfortable and familiar.

That’s something that a Western audience wouldn’t pick up right away.

If at all. I didn’t even know. I discovered only four years ago that the audience was less comfortable with this than with the opposite.

The interesting thing that happens in your work is that you re-orientalize the West. Was that part of what you were doing?

No, I didn’t realize it at the time.

Le Salon Courbé 2007, embroidery, fabric, wallpaper, wood, carpet. Dimensions variable. © Ghada Amer. Courtesy Francesca Minini, Milan and Gagosian Gallery.

Where does the Wild West come into it?

From colouring books. I used to love to draw when I was a kid, especially anything that was a cartoon. I would copy them, and to this day I think my work remains very cartoonish.

When you do the figures that come out of pornography, they’re basically reduced to line drawings. You keep the line as simple as possible.

Yes. A lot of my work simplifies things in that way. It’s almost always the same woman but with small variations. It is also Western women because in my imagination the West has the power. I didn’t want to use a specific race like Chinese or Black. For me the white woman is the one who includes all the groups. You can find pornography about anything, but the problem with a Muslim woman is that when she is uncovered, she looks like any other woman. It is the way she dresses that makes her different. It’s the clothing that makes the Muslim woman Muslim.

It also sexualizes them. This comes up in Shirin Neshat’s work. With the veil you could argue that the covering is sexier than the uncovering. Is some of that sense of a lack of disclosure operating in your work?

But in my work I don’t cover. It’s not veiling. It’s not like Shirin where the woman is covered except for the face and the hands. It’s very different. If you don’t know who made my work, you wouldn’t think it was by a Muslim woman; when you see Shirin’s work, you know it is made by a Muslim woman. She comes with her culture.

How much flexibility do you have with the way you use the thread? Is it a supple enough medium for you to do what you want?

I used very thin colour because I was always afraid that if I used too much, it would move towards craft. My main goal is to make it look like paint. So if I go too much towards thread, there is too much material, and then it would be regarded as craft or women’s work.

One of the interesting things about your work is its rate of disclosure: how much information it gives at what point. Is seeing your work a process of getting closer and closer? Is there a right distance from which to look at the work?

No.

But there are things you don’t see until you get close to the work. What you think is a small figure drifting through space from a distance reveals itself to be a spread-eagled, sexualized woman. Is controlling or directing the gaze on the viewer’s part something that interests you?

Well, I can direct it because I have advanced so much that I know how to do it. Sometimes it is very important where the figures overlay. And there are times when for me the overlay is not beautiful, and not sexy enough where the lines intersect. I do have control. There are also times when I make huge figures you can read from afar, and then when you come in close, you can’t see them anymore.

The Big Black Kansas City Painting - RFGA, 2005, is an impressive scale. What was in your mind in making that piece?

Reza was very much involved with this painting because he did the background and the composition. Then he used the same 24 cuts he had used in his video of a woman travelling back and forth. So it was one of my women structured as his woman going back and forth. We cut the image cinematically.

How do you make determinations about scale?

It’s intuitive.

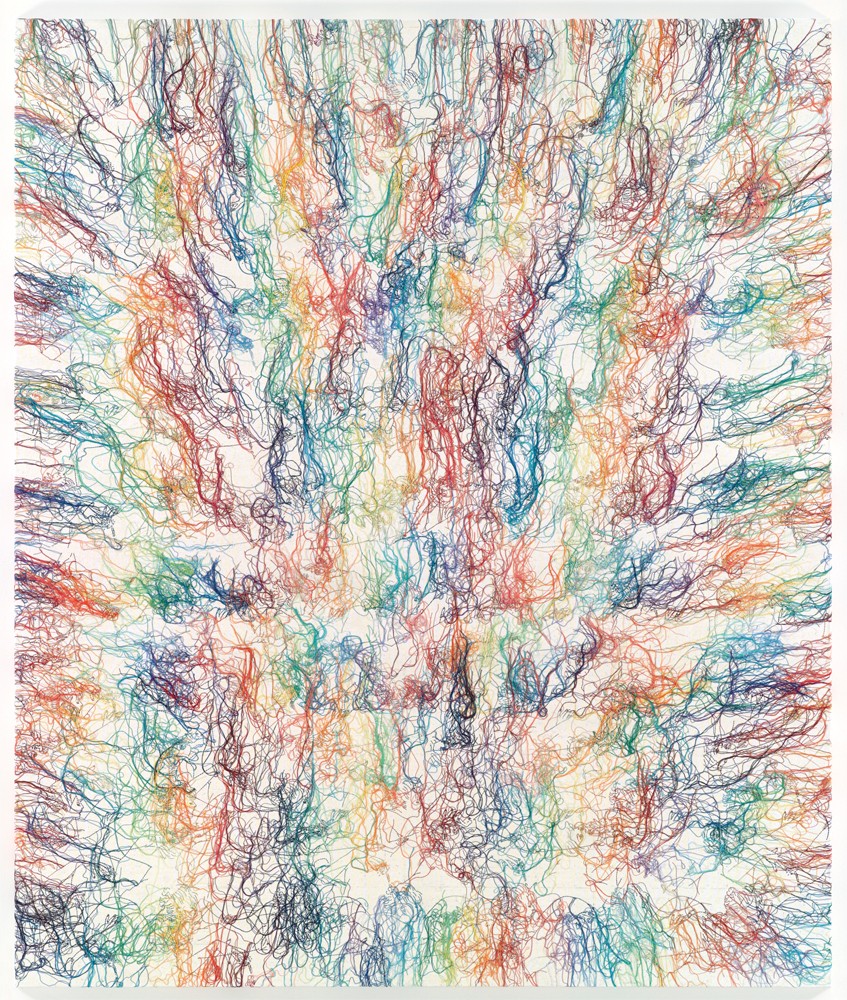

Rainbow Checkers, 2009, embroidery and gel medium on canvas 70 x 59”. © Ghada Amer. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York/Kukje Gallery, Seoul.

Do you set out to do a series?

When it’s done at the same time, it’s a series, no? I look at my paintings, the RFGA series and the non-RFGA series, as if they are continuous. There are big figures and small figures, and I don’t like to cut a series. But it’s not one after another like Picasso in the Blue Period. Because the technique is so tedious, it is very slow, and sometimes when I finish one I am so happy that I don’t want to continue with the same thing right away. My paintings on unprimed canvas now are much better because I have better control, and I also have people to do it for me.

Your piece called Les poufs, 2002–04, a series of nine squares, seems very Matisse-like to me.

Yes. I love Matisse.

But you never set out to deal with him as directly as you did with Albers?

No. Because Matisse is too much of a father figure.

Do you have a sense of shame?

Sometimes. Especially when I did my first show in Egypt. Because the people were so embarrassed, and it was much more political than any other place I have shown in the world. This was in 1998. I am going to publish some pages of my journal from that time describing how it went. I’ll publish them in a Belgian magazine of writing by artists. I sent them to my sister to see if it’s okay because I don’t like to publish my writing. At the time I wasn’t embarrassed, but it was very intense. What’s embarrassing is when people ask you the wrong question. It’s accusative.

How did your father feel about your work?

My father is very proud of me, but my mother hates my work. He is proud of me in principle because he is for the woman and I make paintings and they make money, so it must be good. But my mother can’t figure out what I’m doing, and she doesn’t understand my father’s encouragement and approval. His first reaction was not to say anything, and then he started to read art history. He reads everything that is published on my work. I had to smuggle the catalogue published by Gagosian Gallery in 2006 to him because it includes my drawings, which he never showed to my Mom. She would die. She doesn’t think it’s transgressive as much as vulgar and immoral, and she is convinced people will think I’m crazy and that I have a psychological problem. She does, however, like my sense of colour.

Color Misbehavior, 2009, embroidery and gel medium on canvas, 70 x 59”. © Ghada Amer. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York/Kukje Gallery, Seoul.

Are you surprised by the trajectory of your career?

I’m happy because it was important that I continue to make art. What bothers me is that people have pigeonholed me. It’s very difficult to recognize my drawings and my sculptures, which nobody talks about. Very few people talk about my collaboration with Reza. The main obsession is with my painting of erotic images. There’s very little I can do about that. It’s just how people read my work, and for me it is a limitation. But painting is my daily activity. It’s like a prayer, a meditation. It is my one constant, and then there are the other activities I do. I am able to express things in my painting that I can’t express in any other way.

When you say “like a prayer” I’m reminded that in Muslim culture the erotic writing is connected to the divine. Is there any way that you feel you’re involved in a secular religion?

It’s much more of a Sufi mentality. You find it in the Encyclopedia of Pleasure.

It’s in Rumi, too.

Absolutely, and the title of my show, “Breathe Into Me,” is the name of a Rumi poem. I love him. He is one of my favourite poets. The notion of breath is very intimate, very sexual. I thought it was so beautiful.

Do you want your work to read as intimate?

Yes. But when people buy my work, I don’t like it when they put it in their bedroom. It should go in the dining room or the living room. I prefer the living room, and if it leads to intimacy, I don’t mind. If the intimacy starts in the living room, then it can end wherever they want. It’s intimate for me because I feel it more as pain. I would rather have lived my own sexuality than paint it.

Eight Women in Black and White, 2004, acrylic, embroidery and gel medium on canvas, 84 x 76”. © Ghada Amer. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

So is it about longing?

Yes. This is a very good word. So it’s intimate but a little sad. The pain comes from the fact that it never goes away because you can never satisfy it. I used to think this was peculiar to me, but now I know that it is the nature of the human being.

You just don’t want to get too happy or you’ll ruin the whole thing.

I know. But I want to be happy. I don’t care. Do you mean does the prince come? That will be okay, as long as he’s more than two feet tall, and I don’t want there to be seven of them. ❚