The Space of Not-Knowing

Image and Object in the Art of Erin Shirreff

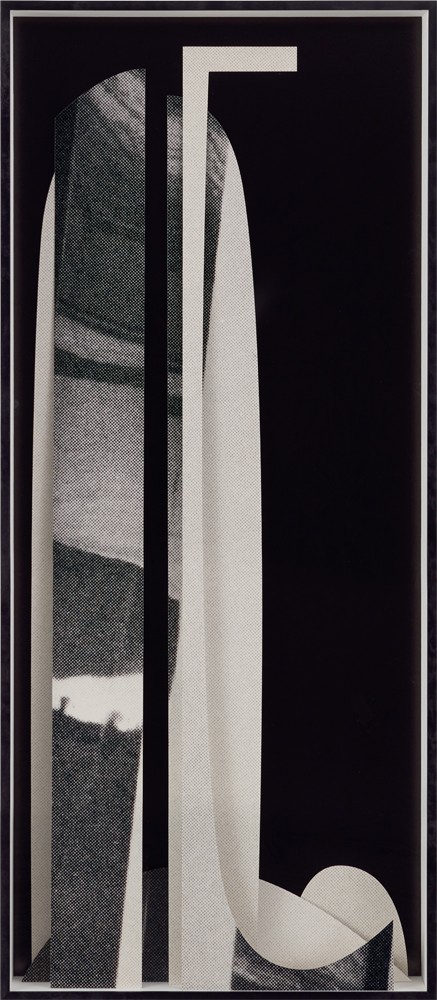

Erin Shirreff, Lacquer, clips and stack, 2018, dye sublimation and archival pigment prints, 88.25 x 37.25 x 5.75 inches. All images courtesy the artist.

It’s my sense that engaging with Erin Shirreff’s work involves an act of faith. Her proposition that time is the elemental dimension in the embodiment of her works, that is, in bringing them into being, is one with which we agree if we commit to her work. It’s this—and I can go with her: her video works (Ansel Adams RCA Building circa 1940, Sculpture Park (Tony Smith), UN 2010, for example), though animated, take as their visual subjects photographs of a structure or an object and amplify their presence through duration. Time is the factor, she is suggesting, that will allow the apprehension of something we can only ever see as a partial form and compels us to absorb and acknowledge its full being, its possible all-the-way-roundness. We have given our time to the object in her video, or to the video itself, have entered into a transient reverie or brief hypnotic pause as we go into or come out of the state and space of the work. We have stopped for a length to allow Shirreff’s question of how we see and take that sense in as perception and knowledge, whether we know it or not. If we go with her work we, too, are asking how, through looking, do we engage what we see in the space we inhabit?

Jenelle Porter, co-curator of the exhibition “Erin Shirreff” at the Albright Knox Art Gallery, 2015 and the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2016, drew a parallel in her essay “Equivalents” between Erin Shirreff’s work and Alfred Stieglitz’s “Equivalent” series, 1925–1934, about which he said his intention was that the work present rather than represent abstract images and emotions. Porter wrote, “Shirreff too proposes equivalences among objects and their representations, literal scale and sensed/experienced scale, and materiality, all within the context of ambiguous definitions of medium.”

Sculpture for Snow, 2011, painted aluminum, 136.5 x 54 x 115.5 inches, installation view: Metrotech Center, Brooklyn.

Equivalent but not the same. Shirreff’s experience of seeing a photograph of Tony Smith’s sculpture New Piece, 1966, and one of the editions of the piece itself installed on the grounds of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University may speak to the potency of an artwork, to the difficulty, as she stated, of seeing a three-dimensional object in a manner inconsistent with itself, i.e., only as a part of its whole, and to the rapidity of our visual apprehension in the digital age. I’m speaking of potency not in the auratic sense, the distinction that Walter Benjamin attributed to the real rather than the copy or reproduction, but thinking here of Erin Shirreff’s comment that some sculpture, to her surprise, seemed to carry less weight in its actual presence than it did as a photograph, and her confession that sometimes in order to better see something, even in her studio, she takes a photograph of it. I like her self-interrogation about the manageability of a photograph rather than the object itself. More time to look at length, or the distance that a photograph allows. Not prevarication but options and ambiguities. Not one thing only, but open-ended possibilities.

The studio is an important site of habitation and productivity for Shirreff, an active place where art is made. This is where the intuitive and the bibliophilic come together and flourish, where both inclinations can be nurtured and pressed to realization. She’s not a street photographer, a documentarian or the capturer of still lifes, although, as she tells us, she likes the active verbs that adhere to photography, like “capturing” an image and holding it fast. But that’s not really accurate, she points out, because photography’s nature is to always be fugitive, to finally elude capture and fixity, resisting its own sealed emulsion through the multiplicity of viewers’ readings.

Sculpture for Snow, 2011, painted aluminum, 136.5 x 54 x 115.5 inches, installation view: Metrotech Center, Brooklyn.

There is a certain unguarded tenderness in extending a desire to be acknowledged or seen and recognized as present to the objects that, Shirreff implies, or perhaps feels, do have presence in the space we also occupy. I was struck by her elaborating on what motivated, at least in part, Sculpture Park (Tony Smith) and Sculpture Park (Tony Smith, Amaryllis). It was her imagining or feeling that these pieces were alone at night in the sculpture parks in which they’d been installed, in a time some distance from the present, alone in the dark, abandoned. This would be a melancholy state, Shirreff suggests, but would also require that these works, so powerful and assertive in their period, continue on and be brave, now. Through Shirreff’s agency there is neither oversight nor neglect, and we see the singular faces these substantial midcentury works offer on a printed surface or as we move around them in their material dimensionality.

In its certitude, which is clear enough to be a manifesto, Erin Shirreff has remarked, art is making something out of nothing and also making your meaning. She tells us that artworks are sites of contemplation, one of the few things made with deliberation for the purpose of being looked at and considered, a route to looking, and thereby thinking through the process of its coming into being.

This interview was conducted by telephone with the artist in her Brooklyn studio on April 19, 2018, six days after the opening of her solo exhibition, “Erin Shirreff,” at Sikkema Jenkins & Co, in New York.

Border Crossings: You went to the University of Victoria, and one of the things it is known for is a tradition of fine faculty sculptors. Did you choose it for that reason?

Erin Shirreff: You’re giving me way too much credit as a 17-year-old living in Kelowna. I had no idea. I was really naïve. I visited the Kelowna Art Gallery a lot growing up, but my high school art classes were not very sophisticated, and I wasn’t a very sophisticated student. UVic was the only school I applied to, mostly because my grandparents lived in Victoria and I wanted to be close to them and my mom had gone to school there, so there was some familiarity, I guess. I mean, I was interested in art at the time, enough to apply to their department, but I didn’t understand it as something I could commit my life to. I remember that first year at UVic I took a mandatory art theory course from Robert Linsley and that was it. The enormity and density and possibility of it all just blew me away. I took studio classes with Fred Douglas and Roland Brener, who both became very important to me, Roland especially. He asked me to be his studio assistant one summer, which sounded so cool but in reality meant stripping paint off his boat every day, listening to Frank Zappa. Roland’s way of thinking and making, his very dry sense of humour, made a big, lasting impression on me.

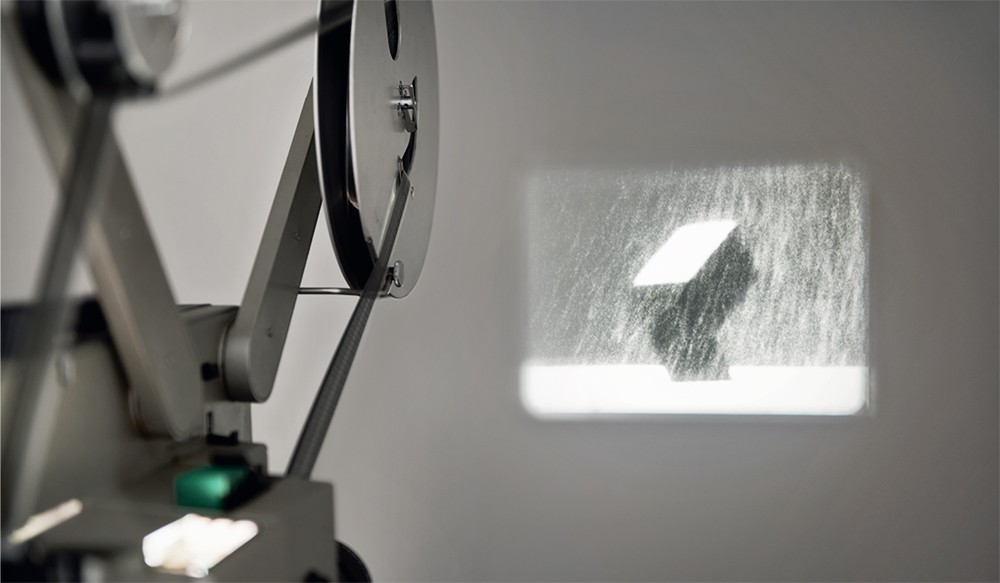

Sculpture Park (Tony Smith, Amaryllis), 2006/2013, 16mm film, loop (8:43 minutes), installation view: Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Did you have some sense that you wanted to be an artist?

Like, as a profession? God, no. How would that ever happen? What would that even look like? That was way too abstract for me at the time. By now I’ve worked with enough students to know that some people exit the womb knowing they want to be professional artists and every day they move toward that goal. Even if they don’t understand what that entails, they’re committed. I’m just not like that. I never had a clear trajectory in mind for my life. It’s always been a series of small decisions. I think I was admitted to the art department at UVic because they weren’t accepting portfolios that year for administrative reasons, which was a good thing because I didn’t have one. They asked me to write something instead. In hindsight those first steps look very chancy.

Did you develop a better sense of what you wanted to do between graduating from UVic and entering Yale?

The day I de-installed my undergraduate show at UVic, I moved down to northern New Mexico with my artist boyfriend at the time, who had suggested living off-grid on his parents’ old commune property so we could pay off our student loans. He was a preparator at SITE Santa Fe, and I started interning in their publications department. I ended up staying and working at the museum in the curatorial department for four years under Louis Grachos, another Canadian. That was my immersive introduction to what we think of as the art world—professional artists, galleries, curators, trustees, foundations—all the components of this peculiar ecosystem. At the time SITE had a small staff and no endowment, and was mounting really ambitious exhibitions and programming. Looking back, I can’t believe the projects I was a part of. My last was Dave Hickey’s biennial in the summer of 2001. The year before I had looked around and thought, “What am I doing? I’m living in Santa Fe and slowly losing my sense of humour and all my friends live in New York.” So after Dave’s incredible show, which was also incredibly complex and exhausting, I left New Mexico and eventually moved to New York toward the end of 2001, which was of course a horrible and disorienting time to show up. I eventually got work at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council with Moukhtar Kocache, who had run the artist residency program in the World Trade Center. I was part of their post-9/11 residency initiatives downtown, at the World Financial Center, the Woolworth Building and other underused buildings. I was there for over a year before casting a net and applying to a number of graduate schools, and ended up at Yale. I had kept up a studio practice in this time but was always squeezed with day jobs; I really saw graduate school as a way of taking myself and my work seriously for two years.

Concrete Buildings, 2013-16, colour video, silent, two channels, loop (73 minutes; 46 minutes), installation view: Kunsthalle Basel, Basel Switzerland.

As you moved through the program at Yale, were you beginning to recognize that you weren’t interested in prioritizing one art form over another? How did your notion of what kind of art you wanted to make evolve?

UVic’s program isn’t separated into departments and that always made sense to me. It’s just “visual arts.” When I was at Yale the sculpture department was where you went if you wanted to do a bunch of different things. Performance, interdisciplinary stuff; some friends hosted a talk show when I was there. The department was very open and all over the place; it still is. I made objects, continued making low-fi photos and videos and explored materials. Jessica Stockholder was the director of the program back then and she always stressed that it was a “professional degree,” which I was never entirely clear on, but it led me to think a lot about the kind of art practice I could imagine having once I left. I recognized a certain restlessness in myself, in not wanting to hew to one mode of expression or one way of making. So I didn’t leave grad school with a particular body of work I wanted to push forward, but I left with a strong sense of my approach to making work.

Your material choices intrigue me. Because you work in so many different modes, I’m interested in how you decide not just what you want to do, but what you want to do it out of.

Probably like most artists it’s a range of things that send me on certain paths. An image will get lodged in my head that I want to see, and then the work will take five different detours as I try to realize it. A lot is borne out of my daily studio practice and processes. Sort of one-to-one to one-to-one. Sometimes literally, as in scraps from one process form the basis of another project, and sometimes as a result of working intensively in one mode and wanting to switch things up. I started working with cyanotypes, for instance, because I felt I was always on the computer staring at Photoshop and it came to feel too disembodied. I wanted to handle things, for there to be texture again. The cyanotype photograms turned out very painterly and I wanted them to have a sculptural presence, so they had to be big; the cardboard forms I made to silhouette in the cyanotype compositions then became steel shapes for sculptures … it goes like that. A lot of it is being here in the studio and moving from one thing to the next and looking around and maybe circling back. Which is maybe similar to how I just described my early years unfolding. It’s kind of a theme.

Well, it certainly isn’t linear. It’s more rhizomatic.

Yes, I try to stay very intuitive in my studio, which can make things seem quite diffuse and murky at times. And it’s true that for the last while I’ve attended, fairly evenly, to a range of different modes. But, for me, looking back, the throughline is always there. Sometimes it can feel embarrassingly logical.

Concrete Buildings, 2013–16, video still, colour video, two channels, loop (73 minutes; 46 minutes).

You have said that the photograph of Tony Smith’s New Piece from 1966 was more powerful than when you saw the actual sculpture at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Have you figured out why?

I think what’s really compelling for me is the not-knowing that is always inherent in a photograph—that you’ll never have a full sense of an object when it’s pictured. There are all those gaps and all that missing information. The photograph of New Piece you’re talking about was taken in the ’60s, and there’s this cool-looking couple standing next to it, chatting. I like thinking about how they experienced that form, because it’s something we can’t know ourselves. We’re not bodies in the ’60s; we have completely different relationships to physical objects now from what people had then. This feels like a confession—and from talking to friends I’m not alone in this—but if I’m making something three-dimensional in the studio, I sometimes take a picture and look at it on my phone. It gives me this other experience of the thing I’m working on that feels really useful. It’s not another vantage point, I’m not seeing more, but the image creates this other relationship by taking it out of your physical space. It dials down the intensity of what it asks of you as a body and allows you the space to regard it. Like I said, I find it useful, but it feels fucked up to do, and to admit to. Anyhow, I’m sure on one level the dynamic at play is simple and related to the psychological sense of capturing something, or stilling something, but it feels more complicated and consequential than that. When I’m documenting things it’s always surprising to see which work I make in the studio that falls apart as an image, just deflates. And then which things come alive when they’re flattened and set apart on the wall. That translation—image into object and object into image—feels very layered and charged to me and really has formed the basis of my practice and my work for the past several years.

Drop (no. 13), 2015, hot-rolled and Cor-ten steel, hanging apparatus, 91 x 62 x 36 inches.

Would you say that your epistemology is more image-based than object-based?

I would say squarely in between. I feel equally engaged in both modes of making in my studio and certainly by the relationship between the two. Is that a non-answer?

…to continue reading the interview with Erin Shirreff, order a copy of Issue #146 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!