The Song of Her Self

The Irrepressible Art of Tschabalala Self

Tschabalala Self is very clear, very focused, very persistent. She says, when queried in the interview that follows, “My work is all about figuration. It’s all about people, lives, lived experiences.” She says, “The main subject of my work is the Black woman, and I care for Black women and I also care about the reputations of Black women as they exist in the real world and also in the collective imagination.” She says about her work for the upcoming exhibition “Cotton Mouth” that she was seeking to answer questions she had about herself and the world around her, more particularly the contemporary state of Black American culture, “because I live in America, but more immediately I live within Black America. I’m very much situated within the reality of Blackness within America, which is a very specific reality.” The current work is a search for catharsis, for answers, for resolution. Questioning to keep moving forward, to bring issues into the larger resistant conversation. To make them visible and recognized.

Claudia Rankine, in her book Just Us, An American Conversation (Graywolf Press, 2020) related a not infrequent experience of standing in a line, preparing to board a plane, to find a white passenger step in front of her in the business class queue, either assuming Rankine must be in the wrong line or just not seeing her at all. The phrase she borrowed, “social death,” is a sociological term she applied to explain her “there-but-not-there status in a historically anti-Black society.” This stepping in front of her was, as she elaborated, “a reaction to the unseen taking up space.”

Bringing racism into the light, making Black culture evident, makes the question and conversation increasingly difficult to evade. Unavoidable in this current period, Tschabalala points out, is acknowledging the pervasive and totally shaping role of pop culture. This, she tells us, is where society’s real values are manifest. “What is valued within pop culture is what the country truly values.” And so America—and alarmingly beyond—has Trump.

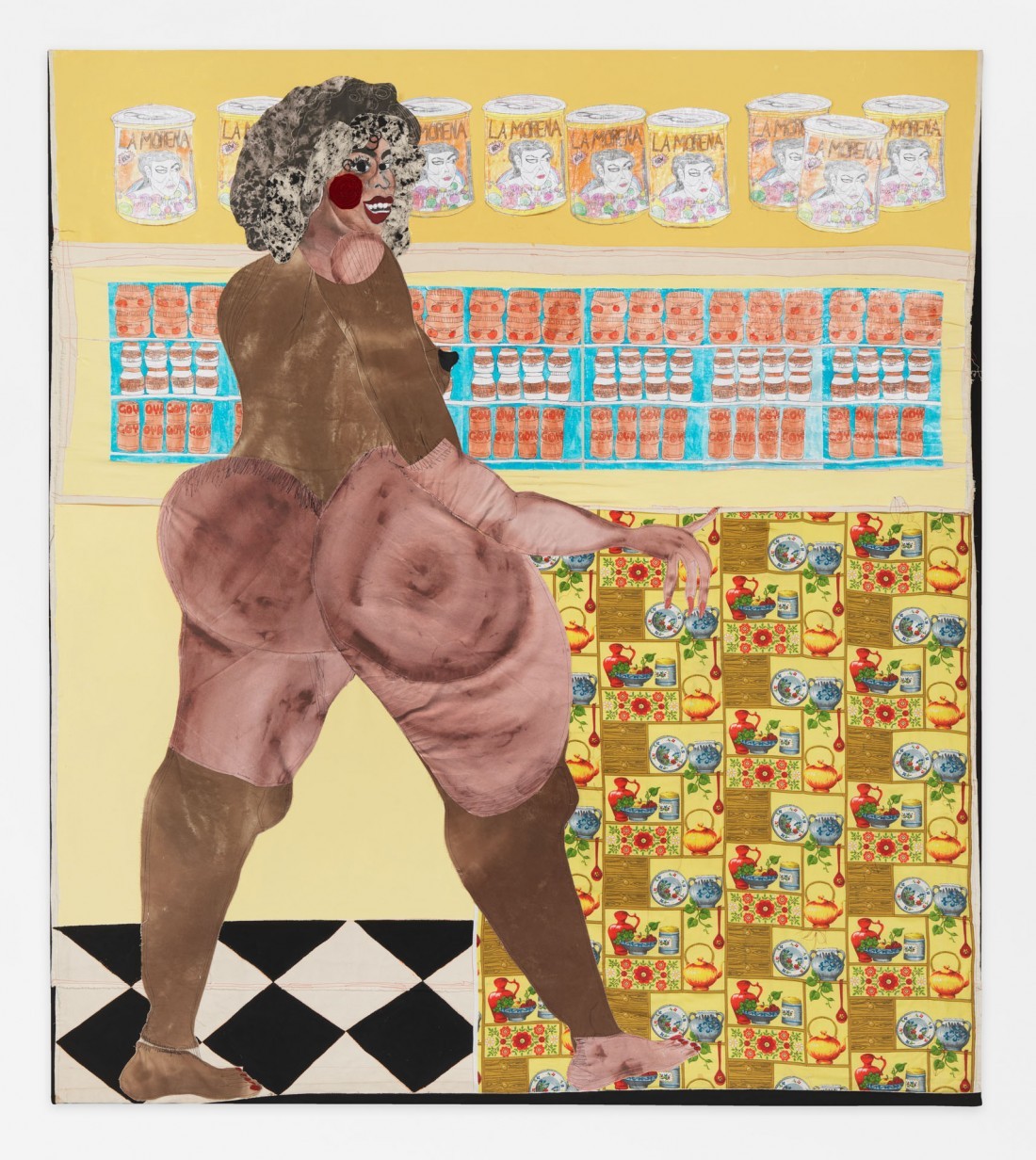

Ol’ Bay, 2019, painted canvas, fabric, digital rendering on canvas, handcoloured photocopy, photocopy, paper, flashe, gouache and acrylic on canvas, 96 x 84 inches.

The work, for Tschabalala Self, must be truthful and, to be truthful, must be shaped from her own experiences. Speaking about specific elements in her work, like her use of repetition, which came from an earlier engagement with printmaking, she draws the conversation, in her focused way, to repetition and seriality, which she sees functioning in an almost hypnotic manner, taking the viewer to a deeper level of consciousness. This gives her the opportunity to turn again to her interest in pop culture and the objects this culture produces in immeasurable volume. “Object” here is key for the manifold ways in which she reads the word and the ideas it represents. She says, “Black America has a particularly close relationship to objects, to merchandise, to cultural output. Black America is married to pop culture in a way no other community in America is.” She outlines the reasons why this may be the case—credible, valid explanations. And then slips in what I experienced as a sucker punch to my gut because of its truthfulness and the pain it carries with it: “It could also be related to the objectification of Black Americans themselves and the use of Black Americans as commodities in the American institution of slavery.” That section of the interview closes with “the realization of your own potential as an object”; “a deeply capitalistic system”; “one in which you have little economic or social capital.” So, Tschabalala’s current exhibition, “Cotton Mouth,” at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in New York is well-titled— rational, cogent, searing and perfect for the time.

The interview began with the artist speaking about the medium she uses for her work. She says she makes paintings, primarily, and sculptures, but the pigment in her paintings is fabric, sewn onto canvas, the stitching allowing for more mutability than would a drawn line or painted gesture. What I see as the capacious generosity of her work resides and is evident, for example, in her choosing fabric as material because she says fabrics have had a previous life, unlike pigment squeezed from a tube. With their history comes memory, and both possess energy, which she believes is transmitted and is ongoing. In the way that she calls on her antecedent Black artists as sources, so the fabric, variously sourced, is also a contributing participant.

The work is arresting in that it stops you in your tracks—a good idea here—to be derailed, since the route we have travelled has taken us nowhere good. But Tschabalala’s work also moves you on, and the direction can only be toward something better, led by her remarkable, courageous work and its unavoidably persistent clarity.

The following interview was conducted on September 8, 2020. Border Crossings spoke with the artist in her New Haven studio.

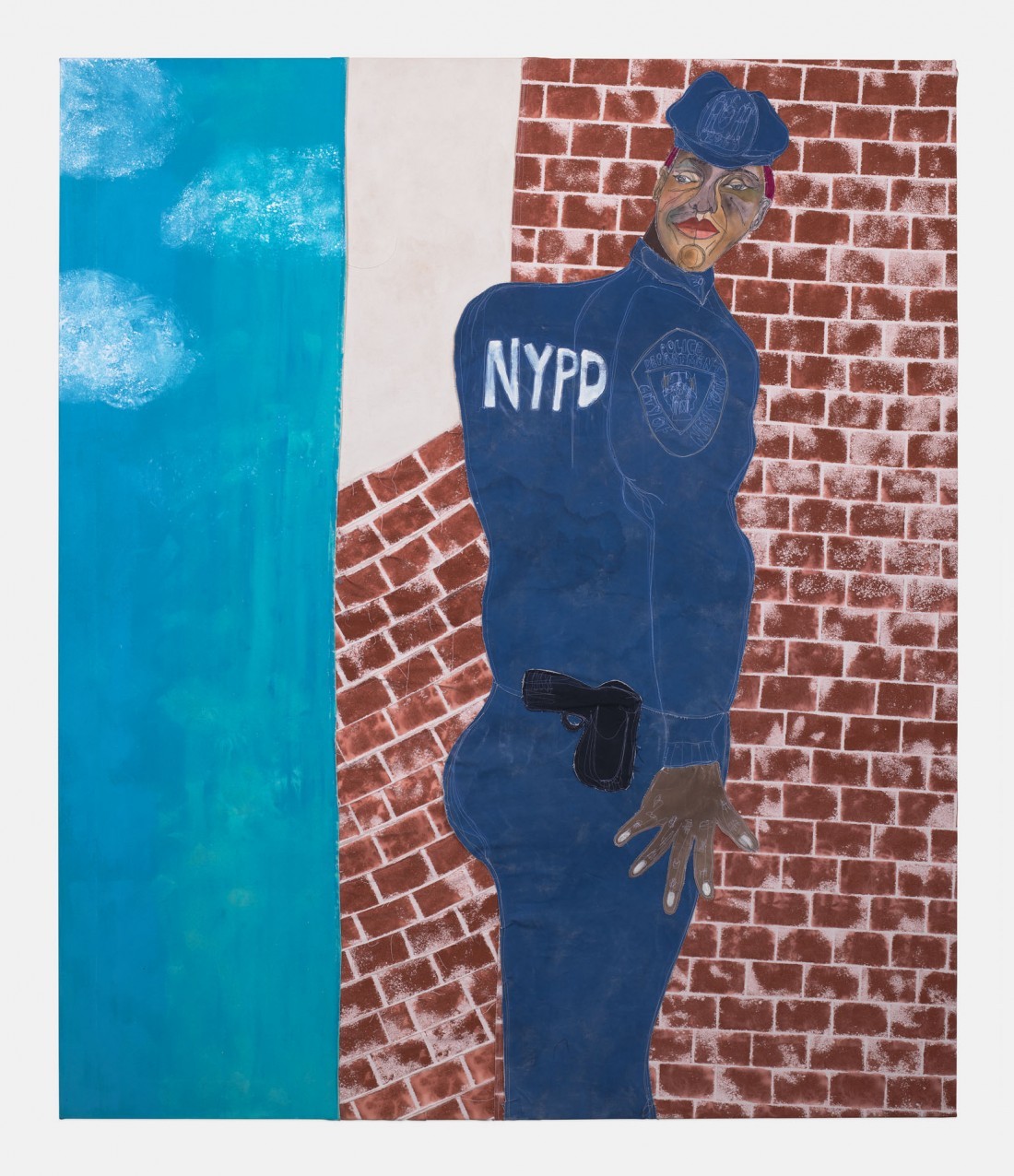

Tschabalala Self, Carpet, 2020, fabric, pigment, paper, acrylic and painted canvas on canvas, 2 parts, each 84 x 72 inches. All photos © Tschabalala Self. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich/New York, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I want to begin by talking about your process of making art and your compositional strategies. In one of the methods you use, you sketch out the figure directly on the canvas or the fabric. Then at other times the figure seems to emerge from sewn-together bits and pieces. Those are very different strategies for making. How do you decide which of them you want to use on any particular piece?

TSCHABALALA SELF: For pieces that are planned out beforehand, I’ll already have a sense of the composition and the silhouette of the figure. I prefer to sketch those out directly onto the canvas. In other works I just want to play with the material and see if a figure, or part of a figure, emerges. It really depends on how thought out a work is prior to my beginning it. Sometimes I’ll start working with the materials and allow for the materials to unfold into a piece; and other times I have a very distinct idea of what I want to actualize and then I’ll sketch out the idea directly on the canvas.

So the material talks to you. It says something and you follow that lead. You use material in the same way a painter would use a palette.

Yes, 100%. And the material is loaded with lots of energy and memories for me. For viewers, the material is loaded with symbolism and associations as well. That’s another reason why I love working with fabric, because it’s been in the world. It already has this energy within itself and I can build on and mould that energy when telling my own stories and use that energy towards my own narratives.

So in a very literal way, a sewing machine is as important a tool for you as a paintbrush would be for a painter.

The sewing machine is just an extension of my hand.

I was struck by the versatility of the stitch as a device; sometimes it’s adornment, sometimes it’s utilitarian, at other times it creates a sense of dimensionality, which is a formal recognition. I guess for you the stitch is an extraordinarily versatile thing to use.

Swim, 2016, fabric, flashe and acrylic paint, 84 x 80 inches.

It is. Also, I love that any gesture can be easily reversed or undone. If I stitch something together and I’m unhappy with it, it’s as simple as popping a stitch to reverse it and start again. I like how mutable the work is and how much space it has to change. That’s what I didn’t like about traditional painting, that mark making can be so much more final, whereas with the stitching, I have much more time to revise and change. There’s always so much of that energy embedded in the work. That’s why a lot of times people say that the figures appear to be moving. I think that possibility for change gives the work this kinetic energy despite its obviously being static and being a painting.

It’s a lovely idea that you can unmake the work at the same time that you make it. That gives you a remarkable degree of flexibility in composing and constructing the image.

The work is definitely as much about construction as deconstruction. All of that relates to some of the larger ideas that are floating around within my practice, ideas about identity, about the psyche, about the emotional self, the public versus the private self, about interpersonal dynamics.

Are they traces of your psychic state as you make them? How close are you to them as the maker?

The works are very close to me because I am producing them. Some of the subject matter in the work pertains to ideas that I am thinking or wondering about. Sometimes they’re things I’m imagining but they’re not autobiographical in any way. They’re just works about ideas and feelings I’m ruminating on; things that are going on in politics, things that are going on in the world, things going on in my world—things I’ve seen in passing, people I’ve seen on the subway. A hodgepodge of a bunch of different things all mixed up.

…to continue reading the interview with Tschabalala Self, order a copy of Issue #155 here, or Subscribe today.