The Bochnerian Not

An interview with Mel Bochner

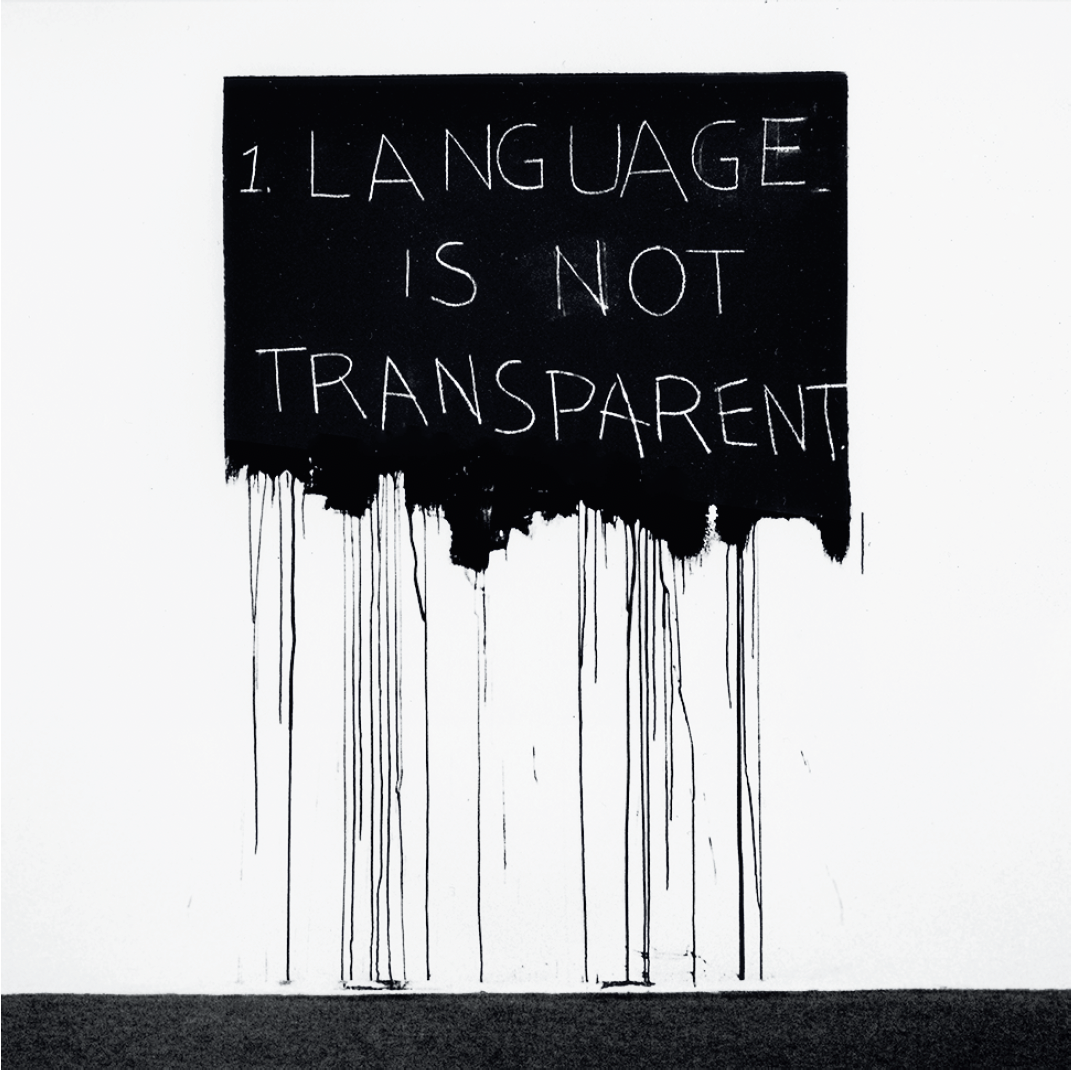

I can’t begin this introduction to our interview with Mel Bochner by saying, “What interests me about his work is …” because everything about his work interests me. What I’ll address in particular, however, is, for me, the Gordian knot, the conundrum of his repeated assertion that “Language is not transparent.” The statement appeared first as a four-part work in 1969, bearing that phrase as its title. A rubber stamp on four notecards, saying once, “Language is Not Transparent,” twice, overlapping on the second card, then three times, I think, the phrase laid down over itself; and then on the fourth card, a multiple stamping, an obliteration of the phrase, not cancelling out but making manifest by way of demonstration, stamped into illegibility on itself. The next iteration of the phrase, in 1970, as though white chalk on a black board, was a wall painting, a statement of a certain kind of independence in its apparently unruly drips running to the floor—a painting but not a commodifiable object—a work that Mel Bochner has done in numerous locations, each one unlike the one before.

Left to right: Mel Bochner, Cezanne Said, 2015, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches; Drool, 2015, oil and acrylic on canvas, 91 x 60 inches; $#!+ $#!+ $#!+, 2016, oil on canvas, 60 x 45 inches. Images courtesy the artist.

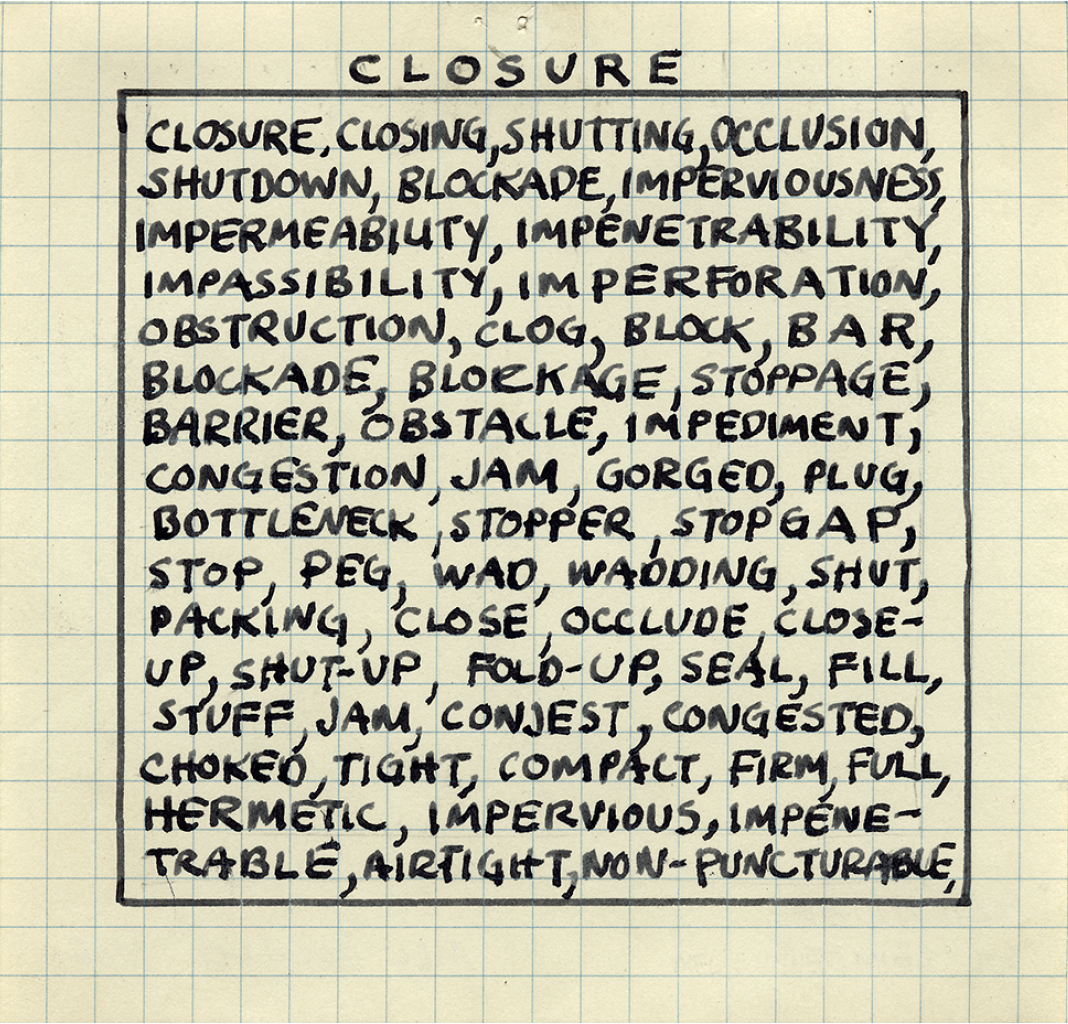

Language is not transparent; that much is clear. We know about its ambiguities, the freight of culture, its failure to be the full parallel or replica or equivalent of the thing it addresses. After he had completed art school, Mel Bochner went back to university to read philosophy. In the thorough catalogue essay for the exhibition “Mel Bochner: Strong Language,” mounted at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2014, Norman L Kleeblatt noted that Wittgenstein’s writings were influential for many artists in the ’60s and ’70s, Bochner among them. In particular, Kleeblatt said, it was because of Wittgenstein’s reluctance to close off on anything, and, he wrote, that the philosopher “urged an incessant questioning of ideas and assumptions,” ideas well-evidenced in Bochner’s work.

So the conundrum: If language isn’t transparent, how do we see through to meaning? Well, we can’t—it’s not possible to read with any certainty. In his interview with John Coplans published in Art Forum in June 1974, Bochner said he felt drawn to Wittgenstein’s beautifully concise summation: “What can’t be said must be passed over in silence.” Speaking with Coplans about looking closely at the work of Kasimir Malevich, Bochner continues, “If you have had any deep experience through your own eyes it gives you a type of knowledge that’s not transposable to any other knowledge. There is an order of thought which is only visible.” And further, on standing in front of a work of art, in this case by Malevich, “Malevich brings us to the edge of language” (Solar Systems & Rest Rooms, Writings and Interviews, 1965–2007, Mel Bochner, An OCTOBER Book, The MIT Press, 2008). More is said in this exchange; I’ve selected lines that seem to address my puzzling through the opacity that “not transparent” could mean. No one speaks better on Bochner than Bochner, and Malevich appears the perfect medium to carry the question of the mutable gap between language and paintings, or text and colour.

Obsolete, 2016, oil on canvas, 88 x 80 inches.

About painting, and leaving behind his engagement with Conceptual Art, of which he was named one of the primary instigators, Bochner explains why, in 1979, he began to make paintings. He tells us in the following interview that this wasn’t the beginning, that he’d always been a painter, just one who didn’t paint. What he introduces is the satisfying idea of “surplus” to explain the difference between Conceptual Art and painting on canvas. It’s a nice word of plenitude, a round word of abundance—enough and then some more—for later. And later is the issue. It’s what remains in the eye, in the being, after the idea has been seen and understood. It’s what he identified in his conversation with curator Johanna Burton in the catalogue Mel Bochner: Language 1966–2006, published by the Art Institute of Chicago, 2007, as “a surplus meaning, a visual meaning … that survives the consumption of the narrative.”

If language is not transparent, what happens when colour is added to it? Is the eye confounded in the oscillating flicker between colour and text, and is colour really more legible than language? Bochner’s series “If the Color Changes,” which he began in 1997, challenges the viewer to settle the eye and see. With work, it can be done but only when you peel the layer of one element from the other; it’s either colour or it’s text but it can’t be both together. But it is a painting, right? So, what’s it about? What’s its subject, the increasingly agitated viewer asks. That’s the subject. The question is its own answer. All the issues/ideas/queries the artist raises in the series “If the Color Changes” and with the “Thesaurus Paintings” that follow are here. His dichotomies, prevarications, ambiguities, screens and covers, assaults and cajoling, the chromatic treats and rewards, the shocks and surprises, the anomalies. Certainty slips away, and the apprehension that can’t be articulated is in the gap between language and colour, between meaning and sensing or feeling. That’s the place art exists, the artist tells us, “in the space where the mental and the physical overlap.”

As for anomalies, I nominate Mel Bochner’s painting Zilch, 2016. Clearly readable, it’s a metonymy, standing in for itself, and, contrarian that the artist is, Zilch is really something! The green painted word sits on its canvas ground proud as a fluffed winter chickadee. There it is, everything and nothing, at once. Really, the last word on nothing, with its unlikeable palette. And perfect, the word’s meaning undercutting its presence, and language still is not transparent.

I want to talk about beauty, a word I don’t think I’ve seen associated with Bochner’s work. It’s my word, not his, but intentionality is his and it is certainly evidenced in the work; the choice of words and colour is not happenstance. When palette undercuts image, an ellipsis presents itself to me in a painting like Howl, 2016, where the title alone conjures the poet Allen Ginsberg, but the language—Snort, Holler, Hiss, Bark, Snarl—has no direct connection to the long poem of the same name, or to the painting’s minty, surfy, ocean-foamy shades of green. But it’s beautiful. As are: Obsolete, Block Head, Blah, Blah, Blah, all from 2016. Here, it seems Bochner is testing his assertion that language is not transparent because, with these paintings, the language does step aside and makes way for a hossana of pigment and gesture on canvas. The words and letters are overridden, and what slips to the fore of perception is pure ocular pleasure, maybe something akin to James Elkins’s alchemical delight.

Language Is Not Transparent, 1969, rubber stamp on notecard, 5 x 8 inches each.

Much of the vocabulary Bochner uses falls short of being words of endearment or praise or celebration, but The Joys of Yiddish, in various iterations, or Jew are a different order. Norman Kleeblatt noted in the catalogue Strong Language that Mel Bochner had told him his use of language was deeply rooted in Jewish thought, with its essential emphasis on reading and interpretation. The tradition of iconoclasm is also his with the Second Commandment’s injunction against the making and displaying of graven images. And he is an iconoclast in the sense of the term’s other meaning—challenging received notions, with some consistency.

There is a hugely satisfying irony in the placement of The Joys of Yiddish, 2013, mounted in Munich in a highly visible horizontal band running the full length of the facade of the Haus der Kunst, an edifice built by Hitler to house examples of art considered ideal to the Nazi sensibility. The gratification of this placement is measured against the painting Jew, 2008. Bochner found a racist litany on an anti-Semitic website where there was ample vocabulary with which to work. The painting is disturbing to read, difficult to look at; the harsh acidic yellow against a terminal grey ground presents with increasing urgency and more agitation as the words build to the bottom of the canvas. The underpainting and the surface drips seem an attempt to feint and elude the ferocity of the epithets being hurled and received. Speaking about this work in a 2007 lecture delivered at the New York Institute of Fine Arts, Bochner said, “All abuses of power begin with the abuse of language,” echoing the words of philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel, who wrote, “It is from the inner life of man and from the articulation of evil thoughts that evil actions take their rise. Speech has power and few men realize that words do not fade. What starts out as a sound ends in a deed” (“What We Might Do Together,” Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity, Essays, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1996).

Mel Bochner told us he sets aside certain ideas, bracketing them to be revisited later. Ideas held early on are brought into the present for reconsideration and to be used anew. Nothing is lost or left behind. A satisfying word picture in my mind is a green and gently rolling meadow. A pacific cluster of sheep moves nicely on. A Border Collie is focused on the task: rounding up, trotting ahead, circling back, moving his charges inexorably forward. Not a straight line.

This interview was conducted with the artist in his New York studio, November 7, 2018.

BORDER CROSSINGS: You have said in another interview that you always thought of yourself as a painter, just not as a painter who painted. Do you have a different conception of yourself now? You seem to have become a painter who actually does paint.

MEL BOCHNER: Yes, I always thought of myself as a painter who just didn’t happen to paint. Now I think of myself as a painter who happens to paint. But at the same time my earlier work continues. For example, that study on the wall is the sketch for a Measurement installation at Dia Beacon, based on an idea from 1969.

Is it your sense that nothing ever gets lost; things are always reiterated or reclaimed?

I like the idea of reclaimed. I don’t think ideas have a shelf life. My job is to continuously try to move forward and let things go where they’re going to go. At certain points an idea feels like you’ve exhausted it, but at another point in your life you realize you didn’t take it far enough. The word portraits of Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt and Robert Smithson sat in the drawer for 30 years until Richard Field was organizing my show at Yale. He came across them and said, “We have to show these.” When I looked at them again I had the feeling that there was still juice left in the lemon, that I hadn’t squeezed it all out. But, at that point, I didn’t know what to do with the idea. It couldn’t be portraits again. I had done that. So a couple of years later I came across the new edition of the thesaurus, which was totally different from the one I’d had in college. It had obscenities in it, which struck me as being a dramatic change in the politics of ordinary language, because little kids use a thesaurus and now it says “Fuck you.” So I started exploring what had happened to the boundaries of public discourse, fishing around in the thesaurus and seeing what I could catch, picking out words that interested me, or that led somewhere, or that I could arrange into a narrative. Going back to the thesaurus was not a return to something from 1966. Then I had chosen a word in advance for Eva; I had chosen one for Sol and one for Smithson. Now I was looking for ways in which the synonyms could create a narrative. It felt like the idea was fresh again.

There seems to be a progression in the Thesaurus paintings. They often start in a positive frame of mind and then the tone of the words begins to shift, so by the time you get to the end of the painting, they’ve become dark and scatological. Is that a personal inclination or simply a reflection of the way the words are listed in the thesaurus?

The thesaurus lists words objectively by parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives. The “dark and scatological” is the intentionality of the paintings. The words are like a fund that I can do whatever I want with. In the earlier ones I would start with a more Latinate and formal language and then let it all collapse. That’s my “personal inclination.”

That it’s entropic?

Basically you could call it entropic. It self-degrades.

So let’s talk about your early interest in language. When you read Wittgenstein, does he touch something in your sensibility with which you could begin to work?

I don’t think there is any direct causal relationship between Wittgenstein and my work, other than what you might call a certain affinity for a way of thinking. What I was looking for in my early work was something that didn’t belong to anyone else. It occurred to me that two things didn’t belong to anybody, because they belonged to everybody: numbers and language. Whatever you did with them, anyone else could have done. So they didn’t have any direct art priority. I was very taken by the Jasper Johns show in 1964, the surprising and mysterious ways that he introduced language into the visual field. And, of course, by his number paintings. But in a Bloomian sense, it seemed to me he hadn’t taken it far enough.

Zilch, 2016, oil and acrylic on canvas, 30 x 24 inches.

So you had to carry the narrative further?

Well, when you’re young you’re looking for a spot where you can build your own sand castle.

You’ve said that previously, as a student, you had been doing a mash-up of Gorky and de Kooning.

There was a different way of becoming an artist in the 1950s. To study painting you tried to paint like everybody you liked. How do you do a Mondrian? How do you do a Dubuffet? How do you do a Gorky? It doesn’t mean you want to be them; it just means you want to expand your vocabulary. But then you reach a point, and I reached that point, where I didn’t know who I was.

You mean you were a chameleon who had taken on the colours of Clyfford Still and Dubuffet and had become them?

I never felt that I was them. I thought I could learn from them, that there was something I needed to know, something I could use. You’re always looking for something you can use. After being out of art school for a couple of years, I stopped painting and went back to school, where I read philosophy but not in any organized way. I was trying to clear my head.

You say your pursuit of ideas wasn’t systematic, but it sounds like you were reading a lot of philosophy and that, for you, those ideas were circulating inside your imagination and were becoming generative.

You don’t really get ideas out of Wittgenstein; you get a manner of being. You can begin to sum up Heidegger; you can sort of sum up Sartre—there’s not all that much to sum up, I’m afraid—but you can’t sum up Wittgenstein. You can never know where he’s going to go in the next paragraph. So there is a kind of mental gymnastics that I really admire. He never stops. He goes over and over the same idea, looking at it from every perspective. Almost beating it to death. There is a relentlessness to what he does. I think that is the aspect of Wittgenstein that mattered the most to me. I never wanted to have a signature style, or material, or a manner of working. I wanted the freedom to follow my thinking wherever it took me. Why should you limit yourself? I guess the best model for that as an artist is still Picasso. He did whatever he did because he had kept open the possibility of doing it. So I always felt that my job was to keep open as many possibilities as I could.

In an essay on Cézanne you say that with every mark he made, he felt it was as if he were the first and only painter. I gather that is not a feeling you would have about yourself as a painter?

Well, once someone else has done something, you can only be second. One of the ideas that interested me a lot in the beginning was Edmund Husserl’s idea of brackets. When you can’t figure something out in math, you set it aside by putting it in brackets. You haven’t eliminated it; you haven’t discarded it; it’s just there waiting for you. So as I started reducing my work more and more, I put all those things aside: “Right now I can’t deal with colour; I can’t deal with shape; I can’t deal with surface. So what can I deal with; what can I do that feels authentic to me?” In the beginning it was just drawing numbers or writing words. Then as time went on I wanted to add things back in to increase the range and depth of the work.

The Joys of Yiddish, 2012, oil and acrylic on two canvases, 100 x 85 inches. Collection of Jewish Museum, New York.

To take them out of the brackets?

To move them into the equation. As you get older you build up a body of work and gradually give yourself more permission. I always thought that if Mondrian in his most classical year—1923 or 1924—if somebody had shown him Victory Boogie Woogie (1944), unfinished with all that masking tape, and said, “You’re going to paint this in 20 years,” he would have said, “You’re out of your mind, there’s no way I’m going to do that. It’ll never happen.” Or he would have had a heart attack and dropped dead on the spot. So if you’re fortunate to work for a certain length of time, there’s a trajectory but it’s not direct. If you want to continue making things that surprise you, you have to go against your own sensibility and see where the contradictions will take you.

The deferral that is contained within the brackets is a lovely notion. Does it mean that the act of being an artist is an engagement with contingency?

Yes, but there are always limits to contingency. Look, if you come into your studio, day after day, year after year, you want to have the feeling by the end of that day that you might have done something you’ve never seen before, something unexpected. If it’s the same old thing, then what are you doing? The place to be is where you don’t know where your work is going. If it doesn’t go anywhere today, that’s okay, too, because maybe it will tomorrow.

The philosophers you’re talking about, including Wittgenstein and going all the way back to Kant, are concerned with the ineffable. Your work and the way that you use language seem to be about that kind of ineffability. No matter how much we declare, “There is always another space; there is always another reading; there is always another hearing.” That’s the sense of contingency I’m getting at.

Yes, and then one day you die.

What about imminence, the about-to-happen?

We’re talking now about something that you’re not conscious of and you don’t really know how it happens. You start with whatever you’re working on and, if you’re lucky, it takes you somewhere. I know it’s hard for a lot of people to follow my work because the different ways I have made things and the different things I’ve thought about might not seem connected. But there is a thread running through it. The interest in my early work is altogether different from interest in my recent work, and that’s fine with me. There’s a limit to how much control you have over reception. Or want to have.

But you describe art as a form of thinking and that happens every time you come into your studio.

Most people consider thinking as a structured thing, but I think about it as a process. While you’re making something, anything, you’re simultaneously thinking about it visually, emotionally and intellectually. You can’t just think; you have to think about something.

When is the first language painting? Is it 1969?

I didn’t start painting qua painting until later, but I guess you’d have to say that it’s the acrylic and chalk piece I painted on the wall in 1970 called Language Is Not Transparent. In that piece I was trying to find a way to bring an aspect of what happens when you make a painting—the painting of it—into a thought. So the drips are not a function of sloppiness; they are a function of un-finishedness, that the work of language and painting can never end. It’s always leaking; it’s always dripping down. And then there are pieces like Theory of Boundaries (1969–70) with the red pigment rubbed into the wall. I didn’t want to work on a stretched canvas because I didn’t want predetermined boundaries to define anything. But as time went on I had no choice. After every exhibition the works I was painting on the wall would be painted out. I wasn’t thinking of them as conceptual art; they weren’t like a LeWitt with instructions that other people could do. Only I could paint them. So in order to preserve the ideas, I had to put it into some form that was not ephemeral.

Did you have a eureka moment in 1969 when you did the stamp piece? Did you know something was really going on there?

Yes, I thought there was something going on, but not where it might be going. It’s like the early “Thesaurus” drawings; it was years later that I figured out I could use the stamps in another way, a painterly way, since painterliness was one of the first things that I’d bracketed out.

Oh Well, 2010, oil and acrylic on two canvases, 100 x 75 inches.

What is your understanding of how the “Thesaurus” paintings have changed over the years?

It’s a pendulum. In the early ones, I painted each letter; each letter is a small painting inside a big painting. I painted them by hand, but so as not to look like they were made by hand. People ask why don’t I use a stencil and avoid wasting all that time. First of all, they’re fun to make, so I don’t think of it as wasting time. Second, you can’t make those paintings with a stencil. But more recently, I’ve been letting things go, letting the act and the tool itself define the image. The large-scale stamps have swung the pendulum to another place.

You’ll use different ways of organizing and composing the letters, so they’ll be in columns right to left, or you’ll begin a series of words, the next line will be a contradiction, and then the following line will pick up the thread of the contradicted thought.

The “Thesaurus” paintings are a lot about voice, about who’s speaking and the tone of one’s voice. I don’t think it is anything that painting has dealt with very well. It’s one of the places where colour comes in because colour sets a tone, in an aural as well as visual sense. The viewer becomes a reader, a very different sense of involvement. The words grab the viewer. Once they see there is something to read, they’re liable to stop and read it. They engage with the painting in a different way, because seeing and reading take place in separate parts of the brain.

Do you mean the reader is optically obliged?

Yes.

Even though an idea is an abstraction.

Exactly. What you hope is that the surplus—which is the painting itself—will outlast the idea. My critique of conceptualism was that the delivery system rarely outlived the idea.

You don’t mean “surplus” as excess, as something left over, or something that is redundant?

Not redundant but something that survives the point when you think, okay, I get it. I want there to be something—the way it is made, the way it is painted, the colour, whatever—that has meaning and value in and of itself. To me, it is important that there continues to be something engaging to look at.

But you want to hold the viewer?

Yes, I want to sustain the engagement. It is not one-shot painting.

Do I Have to Draw You a Picture?, 2018, oil on velvet, 90 x 30 inches.

There are strategies for that through the relationship between figure and ground. Some of them get so subtle that the letters drop out, so to read the painting, viewers have to figure out what it is they are actually looking at.

And you have to work to see it. Because you have to focus and refocus your eyes to even see some of those letters that virtually disappear into the ground colour. So you have to get closer or move back, or put on your glasses. That’s what I want to do: to engage the viewer and hold them there, hope they feel something, which might lead them to think something.

There is an engagement with the looker and the reader, but there is also the hearer. So there is really a triangulated relationship. When I read a painting like Irascible (2006) out loud, I became aware of a series of half and full rhymes. The painting is like sound poetry.

That’s where voice enters the picture. Usually they’re not read out loud, so it’s in your head. It is you reading it to yourself, which is an interesting bifurcation. I am interested in the sound of the words, whether you read them aloud or to yourself. I am interested in a certain rhythm, in a certain metre, but it is not poetry.

So you’re not a concrete poet. The reincarnation of Something Else Press wouldn’t be publishing a book of your paintings?

I don’t think concrete poetry has the same concept of narrative. But there is an equal delight in the nature of language itself. I have friends who are part of the Language Poetry movement in Berkeley and whose poetry I like a lot, but that’s not what I’m doing.

On the other hand, visually you can take a word like “gobbledygook” and the rendering of the painting can reflect the nature of the word, so there is a kind of synchronicity.

Yes, synchronicity, self-referentiality, self-criticality. I find humour in all that, too. Certain words are just funny. Just keep saying “gobbledygook.” The repetition takes you someplace. In making a painting like that, I don’t know what I want it to look like when I start. As I make it I find out what it wants to look like.

The question of humour is critical in the work. In Master of the Universe there is a sense of humour in the phrase “gotcha by the balls,” but it is also not funny. There is a line in a poem by Michael Ondaatje where he mentions Stephen Crane and he writes that “even his jokes were exceedingly drastic.” That’s the way I read some of your paintings.

That’s good, that’s really good.

Blah Blah Blah, 2015, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 inches.

You often use colour in a way that would be counterintuitive to the message of the painting. It is surprising to find a painting with complementary colours and you suddenly realize that its message is not complementary.

Like Drop Dead.

I assume that is a conscious way of using colour?

Conscious, sure, but also intuitive. I don’t want to make the colour obvious, like paint the word “angry” in red. In that sense, I want the paintings to disappoint expectations.

What do you mean?

If you’re looking for a “message in the bottle,” you’re not going to find one.

So is the process one in which you’ll get a word in your head from reading or overhearing something, and that will be the ignition for that particular painting?

I like that “point of ignition,” but you never know when it’s going to happen. Many years ago when both my kids were living at home, one was in high school and one was in grade school, listening to them talk was like living in a language factory. I would hear stuff and say, “Wow, that is a really interesting word, I can use that.” Sometimes I would overhear a conversation on the subway or read something in the newspaper and that would get me thinking. The words could come from anywhere. What I was trying to understand is how we talk now.

And then you go to the thesaurus?

I’ll look a word up and see where it goes. But now because of the Internet there are so many sources for words, a lot of specialized sites, a lot of obscene sites. Several years ago I discovered a virulent anti-Semitic site that gave me the vocabulary for Jew (2008), a painting that upset some people.

It’s not a pleasant lexicon.

No, it leads to a very dark place. But it seemed important to shine a light on it.

Is the counterbalance to it The Joys of Yiddish (2010)?

I didn’t do it as a counterbalance. I called it The Joys of Yiddish having grown up in a home where the language was spoken. We weren’t orthodox like the Hasidim in Brooklyn but we, more or less, followed all the laws.

Gobbledygook, 2015, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 48 inches.

Do you think your father’s being a sign painter had any influence on you?

I’ve wrestled with that question for a long time. How could the answer be “no”? Against my will I was drafted as his assistant and apprentice. I wasn’t happy that he made me practise and practise. As a kid, what did I learn? What did I take away? Well, a couple of things. First: how to work and respect your materials. Second: don’t squeeze your brush!

One of the variations you employ is the arrangement of letters on the page, so you break with the convention of reading from left to right. I’m thinking of a painting like Block Head (2016), where things begin to shift around. What advantage does that give you?

A sense of freedom. The stamps opened the possibility of changing the reading orientation. Upside down or sideways, or even backwards. It became a whole new ball game. That’s the thrill at the end of the day.

And it’s consistent with the notion that you want the viewer to do some work as well, because you have to read that painting in a different way. First of all, you have to turn your head and you have to find which word will act as the bridge to the words on the other two sides. Looking at a painting like that is a much more complicated read.

Yes.

It occurs to me that “Blah, Blah, Blah” is a very useful phrase because you can abstract it more easily. From a painterly point of view, you seem to be able to do more things with it.

I think that’s true. I did the first one around the year 2000. But it sat around for a while before I realized that there was more buried there. It turns out to have almost inexhaustible meanings, which fluctuate by the way it’s painted. The question is: Is its meaning outside or inside the painting? “Blah, Blah, Blah” has different interpretations ranging from agreement to disgust. But essentially it’s just an expulsion of air out of your mouth. It’s sublinguistic, barely even a word. So it can mean anything, everything or nothing.

Your paintings almost always end with a comma, as if to continue. So that orthographic decision carries a philosophical position?

Absolutely, except for one painting.

Block Head, 2016, oil on canvas, 80 x 60 inches.

Doesn’t one end with an exclamation point? You use them a lot in the body of the text, but almost never at the end. You also have one with an ellipsis.

Yes. There are ones that end with exclamation points and I have one or two with ellipses. And one that ends with a period: Die (2005).

Should we read much into the punctuation of the paintings?

Why shouldn’t you?

I’m asking whether you do or not.

Of course I do. It all means something. It means something when I use capital letters, or when I use commas. It has a meaning that both plays on its use in the painting and plays off its use in the world.

Barnett Newman says that “to continue” is to begin again, and “to continue” is also the last of the instructions in Richard Serra’s Verb List from 1967–68. That list is all infinitives and a few prepositional phrases. He says that drawing is a verb. If drawing is a verb, what’s painting?

Well, I’ve said that painting is gerundical.

What makes the gerund perfect is that it partakes of two conditions at the same time. It is a verb that functions as a noun. I see your work operating in that double space. Is that a quest or is it just the nature of human life, that these two spaces are always simultaneously occupied?

It just seems to me that’s the way things are. You want to make your work part of the way things are, yet simultaneously against the way things are. That’s the meaning of the “double space” to me.

You talked about wanting to make a mark by doing something new, which you did in your early criticism. When you reviewed the “Primary Structures” exhibition at the Jewish Museum in 1966, you were only 24 years old but you came on like gangbusters. What gave you the confidence?

I really don’t know. I never set out to be a writer. I was broke and needed a job and I got an interview with the editor of Arts Magazine. He asked if I’d done any art reviewing and I said, “No.” “Well, you’ve done some writing?” and I said, “Not really.” “Well, what makes you think you can do this?” “Because I’ve read them and they don’t look like they’re that hard to do.” He started laughing and handed me a “tryout” sheet with 30 shows. The idea was that every show you wrote about, you got paid $2.50, whether they published it or not. Thirty times $2.50 was $75 and my rent was $21 a month, so I was doing okay writing reviews. I worked my way up and then I heard the “Primary Structures” show was coming and I said I’d like to review it. Turned out mine was the only positive review of that exhibition. Hard to believe, but everyone else slammed it. I didn’t know any of the artists, never met any of them. I wrote about them because their work was the most provocative and they seemed to be interested in certain ideas I was interested in, particularly phenomenology. For me, as an artist, they were the edge.

Nothing, 2015, oil and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 inches.

You do reviews where you’re making things up. Your quotations are real, attributed, invented and lies. What I’m getting at is that you understood something instinctively about how to do something that was new. Nobody else was doing this kind of thing. And you collaborated with Smithson.

I think making something new grows out of an exasperation with the way things are. A desire to think them differently. When Smithson and I approached Sam Edwards, the editor at Arts Magazine, our idea for “Domain of the Great Bear” grew out of our initial frustration with the way dealers would always ask to see your slides. “Would you come to my studio?” “No, we don’t do studios but send me your slides.” We figured, what the hell; why do artwork? Just make a slide and send that to the gallery. That led to, “Well, if a slide is a reproduction, can a reproduction become an original? Can we turn that relationship inside out?” A magazine is a secondary source; it’s all reproductions. Could we make it into a primary source? What we needed was some kind of ostensible subject that would make sense in an art magazine. We were having lunch across the street from the planetarium and we thought it would be funny to write a review of the planetarium as a museum. Sam thought it was a great idea and he gave us eight pages and freedom to do the layout. But we didn’t tell him anything about our real intention, which was to plant a time bomb inside the art system. We got press passes so that we could get into the photo archives of the planetarium. I wrote part of the article and Bob wrote part and part of it we wrote together. We worked out the layout together.

Sections of the article show the mark of Smithson’s writing.

Yes, he wrote the last two pages with the photographs of catastrophes and I wrote the first two pages about the materiality of the building and the exhibits. There is a long section that is my parody of Judd —“Ten windows are clear and transparent. Four are green. Three are red. Two are blue. One is of an indeterminate cast.”—which was both poking fun at his Hemingway style and an homage because he was so important to us.

Important as an adversary?

Yes, important as an adversary. The Working Drawings book started out as a show of drawings, but when I brought them into the gallery, the director, who had commissioned me to do the show, said, “I’m not going to pay to frame this shit.” Fortunately, the school had invested in the latest technology called the Xerox machine. So I said, “Okay, I’ll xerox them all,” thinking I would just pin the Xeroxes to the wall. But after the drawings were xeroxed, they came out all the same size and format and already looked like a book. At that point I decided I could return the drawings. I called everybody and told them I didn’t need the actual drawings because they were going to be xeroxed and shown as four books, which I now considered to be a work of mine. Nobody had a problem except for Judd. He said, “I don’t understand. If you xerox a drawing of mine, how does it become a work of yours?” In his own way he was the only one who really got the radicality of it. Eventually he agreed, even if he still remained somewhat skeptical.

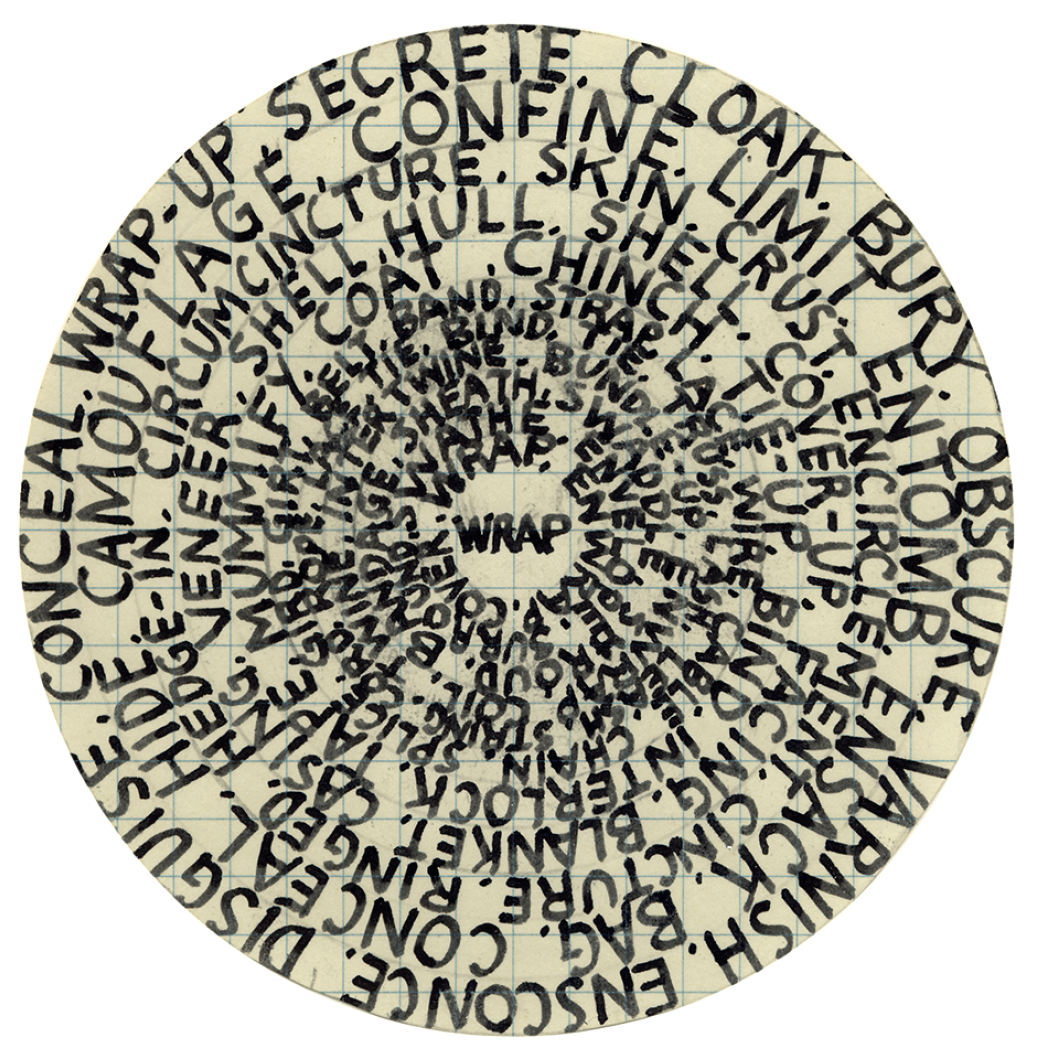

Portrait of Eva Hesse, 1966, pen and ink on graph paper, 4.375 inches diameter.

History has a way of making us aware of what we’ve done, but you couldn’t have known how important that exhibition was going to be.

The way I say it is, “history is what happens behind your back.” At the time it didn’t get a single review. The director of the gallery called the PR department of Xerox Corporation and said an artist has made this work using Xerox and their response was, “Oh, that’s great, we’re going to send a writer and a photographer down there and we’ll get you some publicity.” So the guy comes down and he looks at the book and he looks at me and says, “But it’s just a Xerox. There’s supposed to be a work of art here.” I said, “Yes, that’s the work of art.” I don’t know what he was expecting but four books of Xeroxes were not it. Luckily the photographer decided he might as well take some photos. Otherwise there would have been no record of the exhibition. A lot of artists came to the opening. It was a very lively opening and then it was on to the next thing. But about six months later you started seeing “book” exhibitions popping up in art galleries.

The American poet Robert Duncan has the idea that “if you don’t enter the dance, you mistake the event.” What he was getting at was if you had gone to see a performance by Martha Graham and expected to see dancers en pointe, then not only will you not be able to enter the dance but you’ll also be a lousy dance critic. It says something about the need to find a language appropriate to the thing being written about. To come back to language, that seemed to be what you were all about, finding a language that made sensible the world in which you were living and making. That’s really what criticism was for all of you.

I can’t speak for anybody else. Everybody was coming at writing from a different angle and they were both complementary and competitive. At the time an artist who wrote was considered a heretic. But Reinhardt and Judd were two important models. As were Godard and Truffaut, who wrote to prepare the world for films they had yet to make. Among my immediate contemporaries, I think Dan Graham had a poet’s sense of language, and his writing was much more sociologically inclined. Smithson was just a terrific writer. He was very well read, which was mysterious, given he had only a high school education. I had some formal art education, some background in philosophy. I liked looking at art. I liked words. I still do.

Liking words brings to my mind your earlier reference to Bloom. I assume you’re referring to Harold and not Leopold Bloom, although you do have a painting that ends in “yes” so you could be channelling Joyce’s Molly. But Harold Bloom’s contention is that things are constantly misinterpreted, that we’re involved with a map of misreading. I get the sense that if you were a cartographer, that’s the map you’d be using for navigation.

Absolutely. I have said many times that for a work to remain relevant, it has to be continuously re-misunderstood. The initial misreading is only the beginning. It has to happen again and again. A prime example of that was Smithson’s show at the Whitney many years ago. The New York Times did a full-page Sunday feature called “Robert Smithson: Ecological Artist.” Now this is a guy who had proposed placing broken glass on an island where birds mated in Puget Sound and who poured asphalt down the side of a hill in Rome. He was not an ecological artist, but through that lens his work took on a new relevance. It was a total misunderstanding. As it was misunderstood the first time, it had to continue to be re-misunderstood.

Portrait of Sol LeWitt, 1966, pen and ink on graph paper, 5.25 x 5.5 inches.

Is all language necessarily a palimpsest, so that when you enter its terrain, you’re always entering previously occupied spaces?

Yes. The thing with synonyms, which Roget himself first said, is that no two words ever mean the same thing. You’re moving through different shades and approximations of meaning. That was something I was thinking about in regards to the colour in the “Thesaurus” paintings. I never used the same colour twice in the same painting. They all had to shade off somehow, like synonyms. I would make a drawing recording every colour that went into every letter, and there are a couple of hundred letters in each painting. For example, Oh Well (2010). “Oh” was in Old Holland yellow green, “well” was in Williamsburg brilliant yellow, plus pale grey and cadmium yellow medium. “That’s” was in Gamblin quinacridone violet with a touch of Holbein grey and white. “Goes” was Williamsburg persian rose pure. Some of them got really complicated. “To” was Holbein light red earth and Old Holland yellow ochre deep and Williams cadmium orange and Gamblin Portland grey medium and Old Holland warm grey light plus white, plus Williams quinacridone maroon. This was my shopping list.

That list sounds like poetry to me. I am also interested in knowing how much the painterly tradition matters to you.

There are so many things that you can do with paint. But they all come hard-wired with historical precedents. Let me put it this way: poets don’t have to make up the words they use. There are hundreds of thousands of words in the English language and somebody else has used every word before you. I think that surface, texture, shape, colour, all the traditional aspects of painting, are referents but they’re also, in a way, empty signifiers. So if you can find a way to use something in a different way, it’s yours. There’s a constant battle between necessity and use. I mean, the drips have a literal use for me, signifying the fluidity of language and the draining of meaning. They also indicate that the painting was painted vertically. That gravity was a visual force. If they remind someone of Morris Louis or somebody else, that’s fine with me; it only multiplies the range of references.

Would you like everything in the painting to be instrumentalized in some way? That it has some meaning beyond how it sits on the surface? Is that an aspiration?

I never thought of it quite that way. I don’t think anybody has that much control over what they do, so to aspire to that would probably be futile. But you do try to get as much as you can out of whatever you’ve got.

Language Is Not Transparent, 1970, chalk on paint on wall, 72 x 48 inches. Collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Oh Well makes me think that there is a kind of resignation, a way of living that’s built into the text.

Absolutely. That painting is an homage to my mother. She was a person who was resigned to the way the world is.

Her world or the world at large?

Her world and the world at large were more or less the same thing. My parents were immigrants, so they found a reality that they didn’t help create and that they couldn’t change. That’s the way it is. Shit happens. Learn to live with it. Now, is that novelistic? I don’t know. But it is the narrative of a life.

You have said that in one sense there is no progress and that originality is not something you look for. If that’s the case, does that make all art a kind of ritual?

What I meant was, originality isn’t something that can be willed. I don’t believe in progress per se but I do think there is an edge and you want your work to find it or, again in a Bloomian sense, to transgress it. Is that originality? It’s not progress but I think it is the way we look for meaning in art. You look for something that shows an understanding of what went before, but that takes it to a new place. That’s why de Kooning and Pollock were so obsessed with Picasso, because he had taken art to a new place and they had to find a way beyond him. He was the edge. And I think there is a natural progression from AbEx to pop and minimalism. What came next had to come next. That sounds deterministic but if you wanted to paint figuratively after abstract expressionism, what are you going to do? Richard Diebenkorn? No, Lichtenstein and Warhol are figurative painting after abstract expressionism, because they found a way around Pollock and de Kooning. I know all the arguments against that point of view and it may be that in the current era of pluralism, there is no edge. But I think there is, and you’ll never find it if you stop looking. ❚

…order a copy of Issue #149 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!