Sweetened with Beauty

An interview with Kai Althoff

We inhabit an ether now in this time of plague, more profoundly than ever. We sleepwalk in a state of semi-consciousness, the sole gift of the pandemic; half awake, half drugged. The future suspended, we can go back to the indeterminate space of memory, we can abide in the present or we can flicker like a lighted wick, bending up and back. My sense is, this is a congenial and familiar state for Kai Althoff.

The interview that follows was prompted by the exhibition at Whitechapel, “Kai Althoff goes with Bernard Leach,” in tandem with our own long-standing interest in the artist’s work. We reviewed his exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2008, and in 2016 his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, “and then leave me to the common swifts,” and he figured prominently in my essay titled “Spiritualisme” in 2019. A review of the Whitechapel exhibition is elsewhere in this issue. It is our hope that his presence will hover persistently over our printed pages.

Untitled, 2018. Oil on fabric, 45 x 64.1 cm. Photograph by Mark Woods. All images courtesy the artist.

More substantial than the ether-induced state, this conversation began with the firm materiality of pots, the irrefutable nature and quality of Bernard Leach’s pots, with the utility and the honest and integral beauty that reside in useful objects well made. Inherent in the hand that produces something of efficacy is the maker’s intention to produce exactly what is needed. Its essential quality houses and is the ground on which its beauty resides. If it is useful it is beautiful, brought close and loved. This applies, too, to Kai Althoff’s frequent use of textiles. In his reverence for Bernard Leach’s pots, he had cloth woven by Travis Josef Meinolf on which the pieces would rest, “the most beautiful fabric woven in colors and textures that I deeply wished Bernard Leach would have cherished as much as I do,” he told us. An offering he described as auspicious, produced as it was in an environment of smoke and wildfires.

Asked how his work should be approached, he replied, “Please come as you are, and you will make of it what is You in it anyway.” With this response, which is also an invitation offered in an unprepossessing and disarmingly humble manner, the door to enter is opened. In writing about Kai Althoff’s work, language is both loosened associatively and limited by its inability to describe or assess in any formal or critical way what it is you are seeing and experiencing. But this is his intention—to obfuscate and confound that kind of occluding, distancing scrim inevitably put up and maybe even sought after by critical writing. Why do that, you have to ask, why write that way? The artist’s intention, the work is there in front of or all around you. So, I write, as I did about his exhibition “Haüptling Klapperndes Geschirr” at Tramps in New York in 2018-19, saying the work is like nothing else, is a state, is miasmic and confusing and is a kind of rhapsody. It floats just above the reach of your up-stretched fingertips and descends to engulf you in a chartreuse absinthe cloud of spatial and temporal displacement.

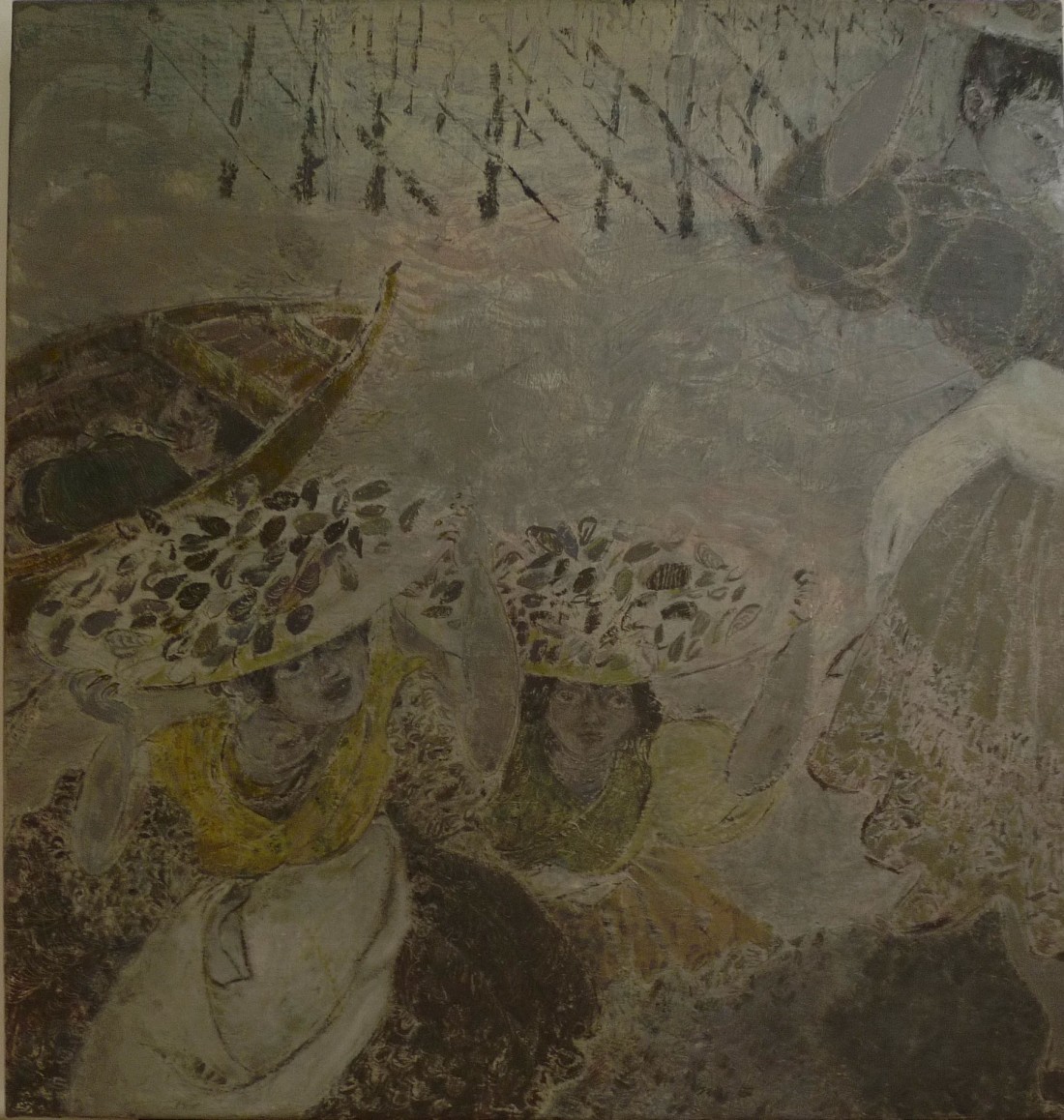

Untitled, 2020. Oil on fabric, 73 x 69 cm.

With works identified as Untitled you are given licence to drift expansively. In Untitled, 2020. Oil on fabric, 73 x 69 cm, a small boat, a rowboat or a skiff for fishing is moored, or maybe not moored but safely close to shore, bumping gently on the water’s surface, adrift only a little, moved by the tempo of a slowly incoming or receding tide some distance off—a blissful bobbing you feel when peril is absent—a letting-go we rarely allow ourselves but, here, safe, and we are grateful to find ourselves in that almost amniotic state of suspension where no decisions are required. A boy rests in this small green dun-coloured vessel, lying on its bottom partially obscured but watching as the three women in 19th-century dress with wide, flounced skirts, loose-sleeved blouses and scarves at their neck ascend the shore’s incline, carrying round, flat trays on their heads like couturier-designed garden party hats but instead supporting generous gatherings of harvested mussels. I’m certain I hear the chorus of an opera I must have seen, as they happily advance. I could be entirely wrong, but will someone return for the boy in the boat or will he follow after them when he gathers strength to do so or perhaps just rest, adrift? The palette is languorous, spare, slow. As dreamlike and expansive as are the drawings and paintings, so, too, are the very particular installations Kai Althoff assembles and presents, with each object a part of a continuing narrative, words in a long prose poem. Patrik Scherrer, writing in the book that accompanied the exhibition “Kai Althoff Souffleuse der Isolation” from 2008, describes the artist’s use of installations as “the logical progression of his treatment of images and sculpture,” adding, “They provide an almost ideal and practically boundless space for the propagation of the many ideas and objets trouvés.” He continues, “They are narrative installations, places of happenings and actions.”

Photographs of the exhibition “and then leave me to the common swifts” at MoMA in 2016 illustrates this. What appears to be a storage space for the exhibition seen beyond is an extended portion of the exhibition itself. The ceilings of all the gallery spaces are tented in a white fabric, to the delight of every child who attended. The mounts or supports for the work are unconventional. In lieu of walls are tiered volumetric shelves on and against which rest paintings, drawings, fabrics, commissioned and beautifully designed sweaters, swags of chiffon drapery, pots, bowls, vessels, toys, drawing books that might have belonged to the artist as a child, and carefully situated mannequins and furniture. In the space that could be misunderstood as a storeroom is a purple velvet sofa, a dolly of some sort on its side, cloths and what might be packing material—all pressed in close adjacency, cozily proximate—one thing to another. On the walls are hung four paintings. In the foreground is the multi-panelled large drawing Untitled, 2010. Coloured pencil, gold ink and tea on paper, 39 1/4 x 50 7/8”, which depicts, in the catalogue’s description by DovBer Naiditch, the transformation of a woman and a man into animals due to their lacking human souls. The transformation is described as painful; the drawing itself is difficult as a depiction. The installations’ spaces contain all the components necessary for a child’s enchantment. I think of my own: a silk scarf, a shiny necklace glittering with faux jewels, a blanket to throw over two chairs for a tent were transformative. Every kid knows this. The spaces provide in their gaps and absences everything necessary. As in Althoff’s installations, they need to be fragmentary and open to elaboration, allusive. The assembled work that is the exhibition remains open-ended: this, also this—an ellipsis.

Untitled, 2018. Oil on fabric, 68.6 x 58.4 cm. Photograph by Mark Woods.

Untitled, 2018. Oil on fabric, 45 x 64.1 cm, is a startle of yellow, a blast of heat, a colour Althoff uses with some frequency, and here as the ground for a vignette framing a tale-telling that is an event isolated from others; see, here; or a tent flap lifted, the fringed tapestry revealing a moment of some intimacy; or a floating world like a large, elaborately painted kite. Two young men absorbed with one another, prone in a flower-strewn field. The man wearing the yellow shirt with red detailing on the cuffs and a blue kerchief at his neck has turned his blond-pouffed head toward the dark-haired man in the foreground. His arms encircle and support the dark-haired figure, his demeanour speaking of care and gently proffered ministrations. He is offering him a scented world to which they both could sail. The dark-haired youth, unmindful of his slender, almost rubbery limbs skewed as though he were a contortionist away from the stage for the day, has turned his head and body toward the blond figure who could promise the possibility of solace and transport. We are watchers but not intrusively so, noting a close moment of connection for which we all long. And how is it, we might ask then, that the apocalyptic yellow sky, which could well be aflame, the trees succumbing and bending to the fire’s hot breath, doesn’t generate alarm but instead some comfort as we yield to our own desire to be warm and held. Perhaps we are reconciled and achieve a glimmer of wisdom. Giving over is a luxury, almost voluptuous; our existence is always a question. This conversation concluded with some discussion of Kai Althoff’s music and the contradictions with which he persistently engages, addressed, too, in his songs—the contradictions with which we also engage, if we are alive. We are born and move inexorably toward death but in-between—the state of wonder and unknowing: Kai Althoff’s work.

…to continue reading the interview with Kai Althoff, order a copy of Issue #156 here, or Subscribe today.