Possibly, Everything: An Interview with Robert Frank

Introduction by Meeka Walsh

Interview by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh

Robert Frank has always produced books of photographs. He made his first one, 40 Fotos, in 1946, a spiral-bound, single edition of 40 images he’d taken between 1941 and 1945 and assembled as a portfolio he would use in seeking employment. It accompanied him on his trip to New York in 1947 and helped him secure work with Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar. In 1948 he travelled to South America and from the photographs he made there produced two handmade copies of a book he called Peru; one he kept and the other he gave to his mother for her birthday. In 1949 he made a small book of Paris photos–Mary’s Book–a courtship gift to his first wife, Mary Lockspeiser, whom he married in 1950. And in 1953 he produced Black White and Things, an edition of three. That book mapped the course Robert Frank would follow in all the work he did. Everything is there: the place of memory, the use of sequencing, a reliance on intuition, the rigour and emotional courage of poetry–and trusting and leaving space for the viewer.

The poetry is important–it’s all important, but like Kerouac wrote in his introduction to The Americans, published in 1959, “Anybody doesn’t like these pitchers don’t like poetry, see? Anybody don’t like poetry go home see television shots of big-hatted cowboys being tolerated by kind horses.” In the interview that follows we talked with Robert Frank about the form of narratives–in his books and in his photographs assembled from multiple images–being more poetic than literal and linear. His response was the elliptical poetry you recognize from the few lines he writes in his books, from the words inscribed on the photographs themselves. “It’s just the friends I have, people I know…. It’s just the people I know and it’s where I live.”

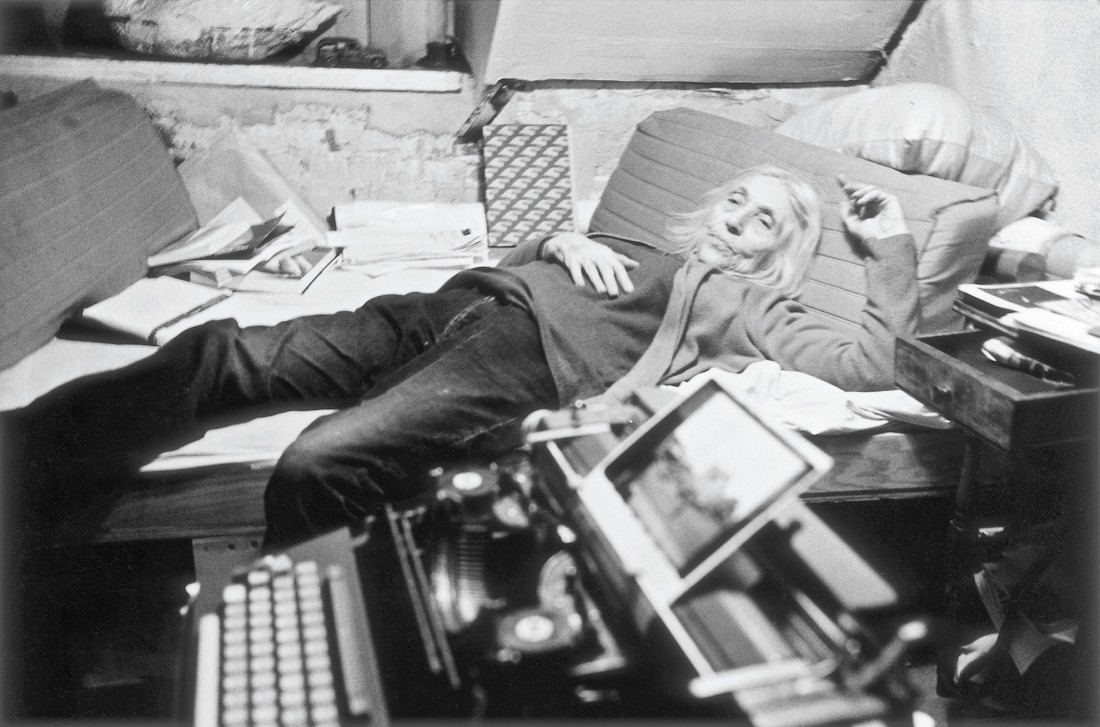

From Me and My Brother, 1964, All images courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York. © Robert Frank

The recent books, Pangnirtung, Paris, You Would, Park / Sleep, Valencia 1952 and Tal Uf Tal Ab, were the provocation for this conversation because, as Robert wrote to us when we’d completed our first conversation for Border Crossings in 1997, “in Mabou interview about intuition and memory for Meeka and Robert and continue….” From the outset of his career, and maintained into the present, he has followed the instructions he printed on the photograph, Mabou in the Winter, 1989–a grey image, soft, the sea in the distance and in the foreground covering a stump, a blaze of snow, white and frothed like steamed milk spilling over onto the ground beside it. The image is mounted on the lower portion of a grey sheet. At the top of the photograph he has written, “Hold Still, Keep Going.” The place between hold still and keep going is the unachievable state in which we live if we interrogate our lives. It is like the very point of the fulcrum on which Frank’s work teeters, seeking only the briefest sustainable balance. It is the existential conundrum–hold still, keep going–life’s joke, that shimmer of equivocation that he has always pursued in his work, and risking the balance, he has urged, “keep going.” In our conversation in 1997 he told us that it was important to continue. “You have to continue and you have to set yourself a real high level.”

Unswerving consistency in the way a life is lived and the work produced, and to be resolute from the very outset, is truly remarkable. But this is so with Robert Frank. The pull against assertions has always been his manner of responding. In January 2013 he told us, “I always knew what I didn’t want. That was the rule in my life. I absolutely knew what I didn’t want; that gave me the idea and the rest was intuition….” Reflecting, and also gentler now in his consideration than he was able to be as a young man leaving Switzerland, he acknowledged, “It’s sad when you know the only thing you want to do is to get away from what someone is offering you. Sad for them. But I knew right away there was no compromise.” And since our conversation at this point had returned to those early decisions to leave, Robert Frank mused on the lives of his Swiss contemporaries, cousins who had visited America for a period, then returned, settled down in family businesses and are well off. “I’m well off too, but my way,” he added, thoroughly Frank-ian. “Everything not to do I learned from Switzerland.” No need to consider if even the smallest sliver of sentimentality had cleaved a narrow wedge in the rigour of his thinking or his work.

June Leaf, Bleecker Street, New York City, 2010, © Robert Frank

But room for poetry and beauty and friends, always. In the opening pages of You Would there is a joyful photograph of three friends: Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky and Julius Orlovsky. Peter and Julius stand in profile behind Ginsberg, so engaged they appear to be chanting, almost devotional. Ginsberg faces his friend’s camera, his intelligent face animated–full bushy beard and lively mass of dark hair capped by a white straw boater with a striped band. They must have stopped on a roadside and are standing in a summer field. The book opens with them because “these are my old friends. They were just walking around on a trip to Kansas and that is how I like to remember them, with Ginsberg wearing his hat. The light was wonderful. There is a certain beauty of a photograph when it is spontaneous.”

Bleecker Street, New York City, 2009, © Robert Frank

In Paris he’d always found beauty too, and light and romance. There were flowers everywhere on the streets, and in his photographs. In Tulip, Paris, 1950, a man in a heavy wool coat fills most of the frame. This is post-war Paris, but he is young and the sure future is ahead, and in his present moment is a young woman, almost not visible, whose eyes, behind her dark glasses, must be seeking this young man who is just beyond her immediate gaze. She doesn’t see him, but he sees her and he holds behind his back the gift of a single tulip. Immanence, romance and hope. New York and America weren’t romantic but they were the place of possibility and Robert says readily, “New York made me. It was my luck to come to America.” It was the place where he could develop his own style, make the work that was distinctly and uniquely his.

But home is another matter. The photograph Mabou, printed in Tal Uf Tal Ab, shows three open doors, one to the other leading from the camera and the nearest door, through the others, to the window and its vertical rectangle of light. The open door, the homely comfort of worn paint and the unguarded access of openings speak of home. When asked about this photograph Robert Frank replied, “I have a good feeling about living in that house in Mabou.” Bleecker Street is a good house too, where he and his wife, the artist June Leaf, have lived for a long time, but the attachment is to the house in the photograph. “It’s a place I have more feeling about. I have much more attachment to the place in Canada. [Bleecker Street] happens to be a nice house but it is still temporary.”

That wonderful contingency, the gently goading and impelling restlessness. Always making work, always questioning, always moving on.

Recent books by Robert Frank include Paris, 2008, Henry Frank, Father

Photographer, 2009, Tal Uf Tal Ab, 2010, Pangnirtung, 2011, You Would, 2012, Valencia 1952, 2012, and Park / Sleep, 2013, all published by Steidl.

This interview was conducted at Bleecker Street in New York on January 18, 2013.

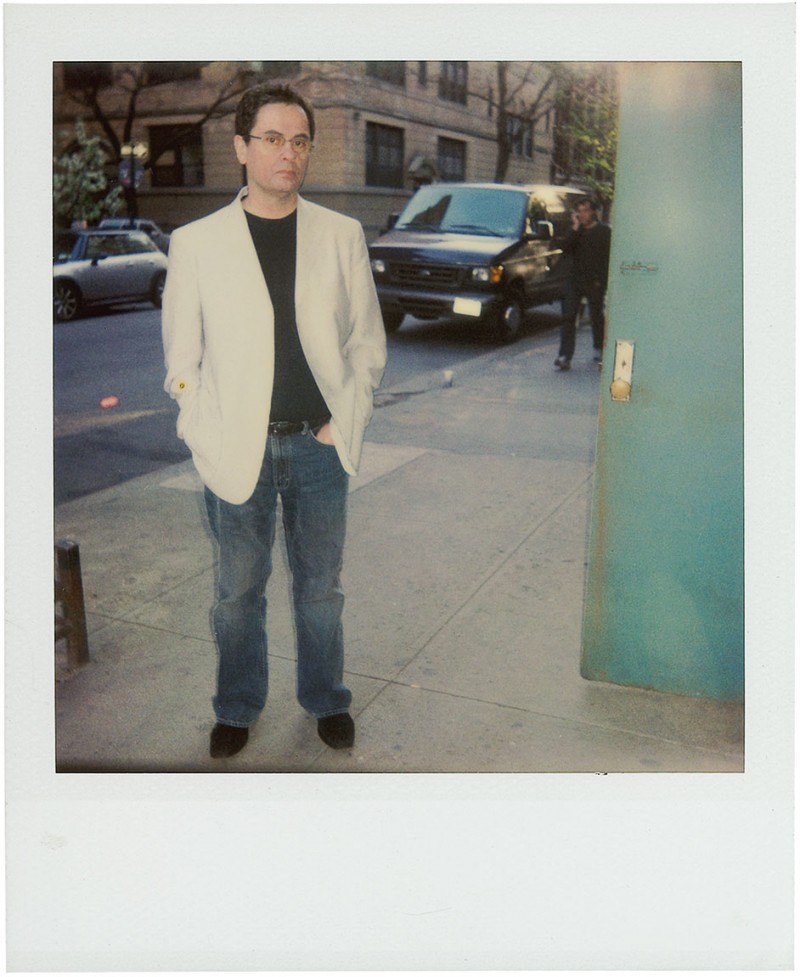

Gerhard Steidl, Bleecker Street, New York City, 2009, © Robert Frank

BORDER CROSSINGS: How are the decisions made about what gets published in the Robert Frank Project? In the last four years six books have come out, and there is already another book in 2013. Do you make those decisions?

ROBERT FRANK: No, it is mostly Steidl who asks me if I have work. I mean, I keep the photographs. I have A-Chan who makes my enlargements and I just choose 30 or 40 photographs and send them to Steidl and he makes the book. I trust what they do at Steidl. He’s a good printer and he does it right and, anyway, I think little mistakes are sometimes the right thing.

Have you been going back through your archive? The time span of the photographs in the books is intriguing. An image of Kerouac from the ’50s will be linked with an image from Pangnirtung taken some 40 years later.

Sometimes, if there is a personality that I want to have in the book, I’ll go back to get a photograph—of Kerouac or somebody else, but otherwise the books are pretty much limited to two or three years. I know it looks like a lot of books but I don’t make that many; Steidl is very productive and he does get hold of a lot of my work and then he makes the scans and sends me the idea of the book and the layout. I agree and say it’s okay. Most often I want less photographs than he suggests.

But are the image-to-image arrangements in the book decisions that you make? Is the sequencing essentially your determination?

Yes, I do the sequencing. Sometimes I have a text or an idea and I put it in. It can be something I’ve saved from a conversation with a guy, mostly about Switzerland—I think it’s quite amazing the ideas they have.

Is your memory so good that when you are doing one of these books you can remember the image you need? Do you remember everything you took?

If I have an idea of making a book from the last five or ten years I go back to the contact sheets because most often I have made the prints before. Whenever I see something good on the contact sheets I choose the good print or I have Ayumi make another print that is better, and that is how the books are made. I don’t work that long on it; only every three or four years a book comes out. But Park / Sleep is the last one.

You have always constructed narratives more out of a poetic sense than a literal one. So what was the idea behind You Would?

Paris, 1950, © Robert Frank

Let me look at it. I don’t think there’s a big idea behind it. It’s just the friends I have, people I know. That’s the book, really. In this one I liked the hand of Nixon, which was part of a job I did in the ’80s. Very seldom did I put something in from an assignment.

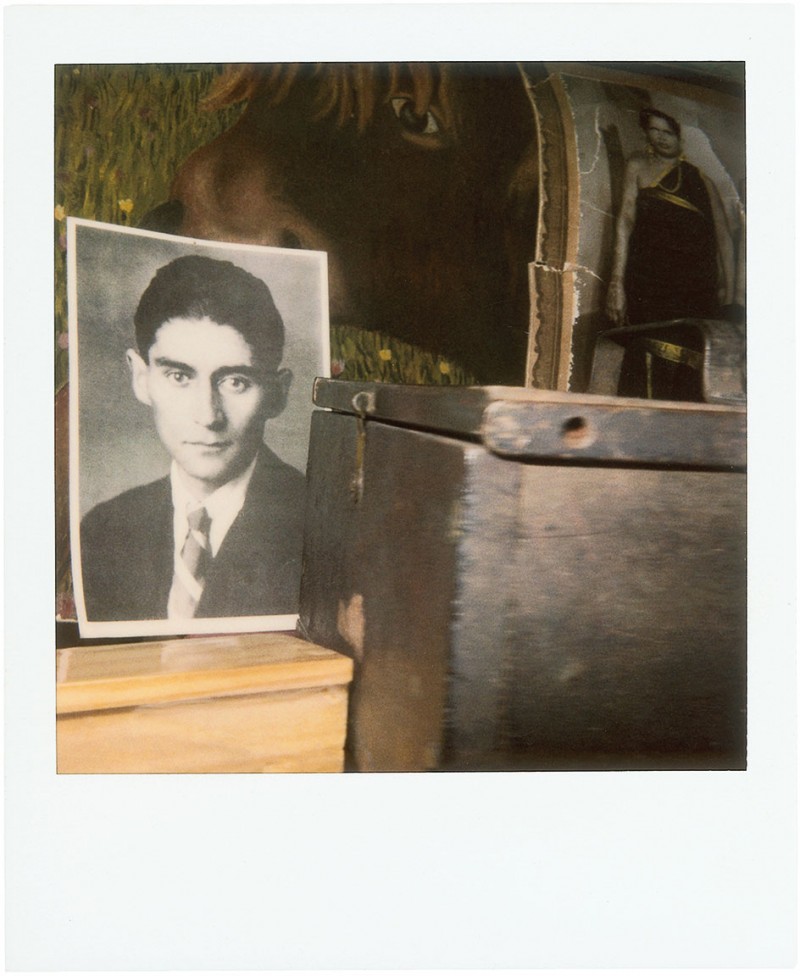

Next to Nixon’s right hand is one of only four colour photographs in the book— the clouds, the line from a Rolling Stones song and then a Polaroid of Gerhard Steidl beside another Polaroid of Kafka here on Bleecker Street. What were you thinking about in pairing those two images?

It’s just the people I know and it’s where I live. A lot of the pictures are in Canada, where I like to photograph because it is beautiful, and then I go back to old pictures. This picture is from Mississippi and it is one of the first pictures I took in America. Next to it is a photograph of Truman in the car.

His open car is speeding down Park Avenue in New York City in 1948, and there is a large flag attached to the front bumper. Do you know that in The Americans there are six photographs in which the American flag appears?

First of all, it is a good-looking flag and you can’t go wrong with it. But there aren’t that many flag pictures in You Would. These are friends. Like the guy who sells guitars in his shop in New Glasgow; or my lawyer from Los Angeles and his boyfriend; or my friend from Portugal, who is quite an amazing guy. He collects cactuses. This is taken by Paolo Roversi, an Italian photographer, who came to visit. This was my best friend in Switzerland, he’s a geologist and he was an important guy, but he must have disappeared because I haven’t heard from him anymore.

June turns up in a number of the photographs and when she appears, it’s almost as if she’s an actor in the theatre going on around her.

Well, she’s a very social person and she is interested in people and people are interested in her.

Is Alberto Aspesi the clothing designer whose clothes you put on people from Cape Breton for a fashion shoot?

Yes, he told me he didn’t care who I put the coats on. He’s a very special guy. He said do whatever you want, so I photographed some old men in his clothes. When you have somebody like that you can work for them and you can do good work. It is the only way. When people tell you how to do it or what to do, then it doesn’t work.

Here is an interesting pair: a series of erotic shunga images opposite an innocuous restaurant wall menu on the facing page. That’s clearly a choice you made?

Well, it’s the same idea. This is very nice. It’s French. I think it was a scroll that was rolled up. It’s sitting on a very old, heavy, large tool that I have around here somewhere.

Early in You Would there is a picture of Ginsberg, Orlovsky and Julius. Why was that the opening foray for this book?

Because these are my old friends. They were just walking around on a trip to Kansas and that is how I like to remember them, with Ginsberg wearing his hat. The light was wonderful. There is a certain beauty of a photograph when it is spontaneous.

Pangnirtung, N.W.T., 1992, © Robert Frank

In Tal Uf Tal Ab I particularly like the Mabou photograph looking through three doors towards a window. Did you know that was going to be a good image?

Well, I just do it because I saw the shape of the window and I think I can add something to the mystery. I’m lying on my bed and I see the doors. It was how they made these houses. These old houses had a beauty that new houses don’t have. They’re cold. I have a good feeling about living in that house in Mabou. I like this house on Bleecker because I’ve lived in it for a long time but I’m not attached to it like I am to the house in Mabou. It’s a place I have more feeling about. I have much more attachment to the place in Canada. This is just temporary. It happens to be a nice house but it is still temporary.

Do you think of New York as temporary as well?

Well, I am conservative. We could have sold this house many times. But I don’t want to change it; I like the place for what it is. It’s not my idea to make it bigger or paint it. Now you couldn’t even paint it because this side of the street is protected. They are making an attempt to save what’s here and this is a fairly nice row of houses.

The landscape seen through the window of an open car door in Mabou puts me in mind of the photograph you took with the girl framed inside the hearse door in London.

The photograph in London with the child running away from the hearse was taken when I photographed every day, looking for pictures. This is different. I am in a peaceful place, nothing happens and nobody is around.

One of your most moving photographs, called Sick of Goodbyes (1978), is a recognition of loss. I have a sense that the images in these books are much happier.

Well, it’s my life and it’s happy because these are my friends and they are people who I feel good to be around.

Who is Reginald Rankin and how did you end up going to Pangnirtung with him?

He’s a really good Canadian friend from Mabou. He’s now in Halifax and he has political aspirations. His father had the Co-op in Mabou and was very important in Cape Breton, so Reginald walks a little bit in his footsteps. Back in the ’90s he had a job in the North. I went there because of him and that’s how the Pangnirtung images came about.

If I hadn’t known that you took these photographs, I still would have recognized them as Robert Frank photographs. You managed somehow to make even a remote Arctic settlement of Pangnirtung your own.

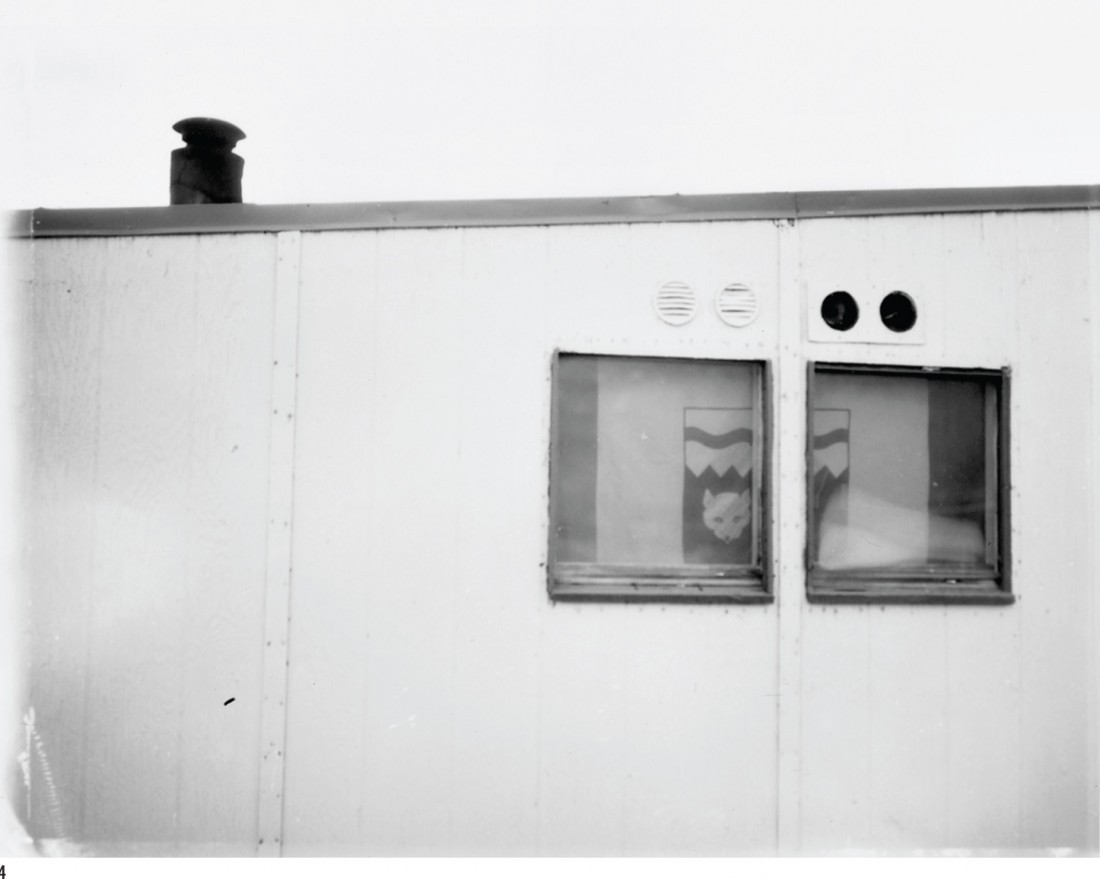

But this was a place where there were only stones. There were just stones in that place, round stones, which you can see on the cover photograph. The houses are these boxes that are brought in and people live in them; they give them oil to make sure nothing freezes. You know, I am attracted by extremes and the life there is extreme. It was difficult with the people. I don’t like to just photograph people because it is kind of an intrusion. If I had lived there for a few months, then it would have been possible to take photographs of the people.

You are right about the extremes, but the opening photograph of Pangnirtung Harbour is romantic and moody.

It is idyllic but it is also tough there. When you go out in a boat they take you to a place that may not be the best place to make a photograph. And I am always attracted maybe a little bit more to it because it makes a stronger photograph.

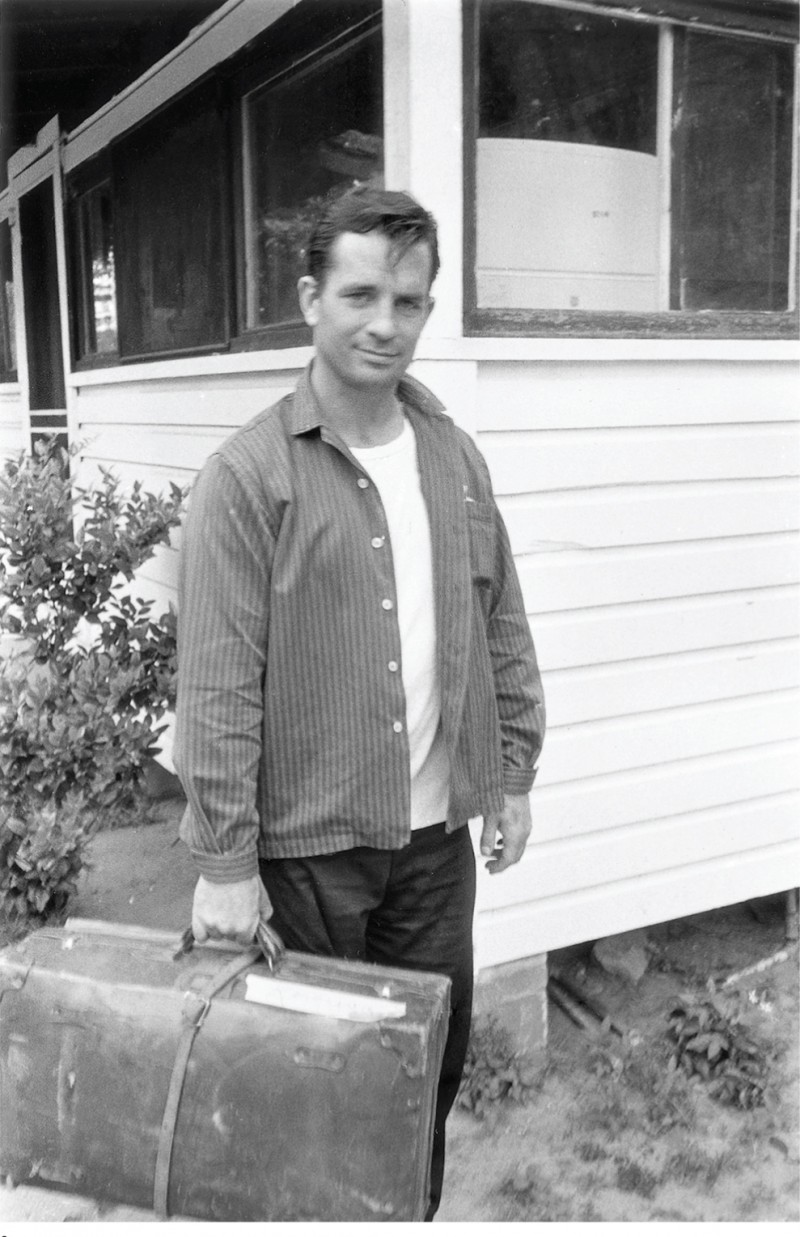

You use a photograph of one of the houses in Pangnirtung as the last image in Tal Uf Tal Ab and on the left-hand page is a photograph of Kerouac. Why that combination?

I have very few photographs of him. I put it there because I wanted to close the book with him, and then there would be nothing else. That was in Florida and it was after the Guggenheim trip.

Pangnirtung, N.W.T., 1992, © Robert Frank

So why is the last image in the book from Pangnirtung?

Well, Kerouac’s got a suitcase, so he’s going somewhere.

What does Tal uf tal ab mean in Swiss German?

It’s a Swiss saying that is often used. Up is basically the direction you go in Switzerland and sometimes it’s a long trip. Mountain climbing was one of my base experiences. It was the way you travelled, starting at four or five o’clock, early in the morning. You would go slow and every 15 minutes you would stop. That was a better education than I got from all my schooling as a child. Life outside in nature. When I went mountain climbing and skiing, those were the best times I had in Switzerland. That was the best school.

Was your father an outdoorsman?

Only in a car. He never walked a block. He wanted a good life. I always knew what I didn’t want. That was the rule in my life. I absolutely knew what I didn’t want; that gave me the idea and the rest was intuition. Then coming to America I didn’t want to fit in to the way photographers did commerce. I could see I had choices.

I was surprised to learn that before you came to America you had only seen one black person—a woman—and you didn’t know what a homosexual was. How sheltered was your upbringing in Switzerland?

Well, at the time I grew up there were no black people in Switzerland. There was one black women living in Zurich. It was a very isolated life. I don’t complain about it but it was cut off, especially when there was war all around the country because of the Germans.

When you say you always knew what you didn’t want, did you also know what you did want, and was it America?

It was the obvious place to come. In Europe the Jewish middle class learned English and so you would go somewhere where it was spoken. And most people of that class who were my age, my cousins, would come to America and stay for six months and then go back, each one of them. I’m the only one that stayed. Because for them life was good; there were no surprises. You knew what you would get staying in Switzerland. They had their families and they took over the businesses and they all were well off. I’m well off too, but my way. Everything not to do I learned from Switzerland.

The only American you met was this man who came to your father’s house for dinner and he proceeds to fall asleep after eating?

That was Mr. Callaher, a guy from Chicago. We were just so happy to have an American come to our house. My father imported radios from Sweden and from America and the guy came to do some business with my father. It was the only time that someone had come for dinner that I had any interest in.

And then he falls asleep?

Well, my father also slept, every day on the couch. He would smoke a cigar and then he would fall asleep. Then he went to a café. In a way, he was a bon vivant but he had a business. All the conversation at the dinner table was about money. My mother was a sad woman who had bad eyes and she became blind by the time she was 40. She had a hard life but she was a brave woman. Her father was a Russian immigrant who started a factory for bicycles in Basel and did very well. He was a very smart guy but my father didn’t get along with him. He didn’t talk much and he was different. I think he died when I was about 12.

What was the reason for doing Henry Frank, Father Photographer, the book of your father’s photographs?

That was really because of François-Marie Banier, the French guy. I showed him some of the photographs. But my father wasn’t serious; he just liked to take photographs. He had glass plates and quite a good camera. It was funny, I remember coming back from America, and I already had a job and a book published, and my father said, “I’m a photographer too, so now you can enter the business.” He had absolutely no sense of it. But he liked me better than my older brother. He knew he would have trouble with my brother, so he wanted to persuade me to enter his business, but I knew I would never do it.

Pangnirtung, N.W.T., 1992, © Robert Frank

Did he know it, too?

I think so. But he tried. I knew I would never want to live the way he did.

When did you start taking photographs?

I think I got a Rolleiflex for my birthday before I left. I apprenticed with a very nice older man who lived on the top floor of our apartment building. He was a retoucher and I said, I want to learn from him. My father said okay, he liked the man and he could see that he was somebody good, so there was no point in arguing. It’s sad when you know the only thing you want to do is to get away from what someone is offering you. Sad for them. But I knew right away there was no compromise. I had to get away.

Compromise hasn’t been one of your major characteristics has it?

Well, maybe it is a kind of egotism; you wish to be successful or be better than someone else. I had that in me to compete and to come out on top. Coming to New York and becoming a photographer was tough business in a way, with all these fashion photographers.

Did you also know what it was you didn’t want to do when it came to photography?

Well, I had to find out. I knew I didn’t want to be a fashion photographer, but that was where the money was. Alexey Brodovitch, who was art director at Harper’s Bazaar, was nice to me and he said, “Well, you can make these little pictures for the shopping section in the back of the book.” So I made five or ten pictures and for each picture I think I got paid $30 or $35, which was a lot of money at that time. I was lucky, but then I went to Peru right away.

Why did you choose Peru?

I saw books and it was a far away country. It was adventure. It’s a very beautiful country to travel in. It was romantic; just the opposite of working in America. There are no romantic places here.

But when you first came were you astonished by America?

Pangnirtung, N.W.T., 1992, © Robert Frank

Yeah, and I knew I wouldn’t go back. An old German guy took me to Times Square for two or three days and when I saw that I said I would never go back to Switzerland. It was very strong, all the people and the traffic and everything. It was simple. You had the feeling that this was where it was happening.

When you began to take photographs did you also know who you didn’t want to look like? When you go to Paris you shoot at night, and you must have known Brassaï’s Paris by Night. Were you already looking for a way to do Robert Frank night photographs?

Intuitively you know as a photographer that you have to find your own style, something where people can say this is a photograph by Robert Frank. This was the dream I wanted to achieve. So I worked for that. Intuitively it felt right to do that and I didn’t want to be like the other photographers who I got to know here, mostly guys who came from the army after the war and who became quite well known fashion photographers.

In your night photographs in the Paris book there are no theatrical images, like Brassaï’s Bijou in Montmartre. His images are shot in-close, whereas yours are more middle range and they are not demimonde pictures. Was that a deliberate way of not doing an image that had already been done?

I don’t know how conscious I was not to, at that time. I had it in me not to copy and not to be too much influenced by somebody else. But I liked his photos and I went to see him.

Did you have to avoid Kertész as well?

No. I thought he was a very good photographer. There was a difference in how he photographed; there was more sensitivity. He had a book called Day of Paris that was a very good book.

There is one photograph in your Paris book of a woman lying on the ground, foreshortened and with a bouquet of flowers next to her, that reminds me of Kertész.

Jack Kerouac, 1964, © Robert Frank

Well, he certainly influenced me. I knew his photos and I knew him, too.

Was it natural for you to call on other photographers? Was there a kind of brotherhood?

In Paris it was easy because they all lived close by. And I was the youngest.

Did your experience in America change how you photographed Paris when you went back after a couple of years?

I wanted to find a place in Paris. I knew people but I couldn’t find a place and I also knew I wouldn’t get paid. I couldn’t make a living there as a photographer but here I could. It’s simple. Here everything was possible. I didn’t know that and I would not say that but I thought it was possible here. And I still think that. I still do think that. New York made me. It was my luck to come to America. And then I went to Canada. The smallness of Switzerland had had an effect on me. I realized what a small, threatened country it was, especially for a Jew. You were near disaster, so you wanted to get away.

In the Paris book there are a number of lovely photographs of couples—the young man with the tulip, the older couple in the Tuileries. There’s a real sense of romance in the images you take there.

Yeah, it was my age and my love for Paris. You couldn’t love New York, but I really loved it there.

The photographs are atmospheric, even lyric.

It was the city that made that. Wherever you looked there was beauty, in the buildings, the parks, in a lion monument in the 14th arrondisement. Wherever you looked, it was easy to see the qualities of Paris, the light.

You choose six of the Paris photographs to put in Black White and Things when you put together that book in 1952.

But there were probably even more photographs from London. I thought they were stronger and I felt that was a period I wanted to get away from. I went to Spain, too.

What drove you to change so much? The blacks in the London and Wales photographs are dense and rich and you immediately leave it behind. Were you restless by instinct and didn’t want to repeat yourself? You never settled for very long.

Pangnirtung, N.W.T., 1992, © Robert Frank

I think it was the influence of America once I tasted it. I came here and went back to Paris but I think my intuition told me that the real thing was America and not Europe. I was clear about that.

You said that you knew what Walker Evans’s images looked like and you knew what you didn’t want. But interestingly, you took a copy of American Photographs with you in the car on your road trip across the country. Was it a tribute or a reminder of what you didn’t want to do?

Well, his photographs had a big influence on me and I did go to some of the places he suggested. He was the photographer who influenced me more than anybody else.

More than Bill Brandt with his miners?

Yeah. I helped Evans doing his jobs. The way he photographed influenced me because he looked at it straight. That was his lesson; he photographed it just straight. It was very strong to learn that from somebody who did it without compromise. We got along very well. He liked me and so he would tolerate me. But he was not a nice man. He believed in breeding, in good schools. But when somebody was good, he would stand up for them. I went to see him later on when he was not so well and he would lie on his bed and say, “Don’t bring any of those Ginsberg guys. I don’t want to see any of those types. Don’t do that.”

Walker Evans’s introduction to The Americans was pretty tight ass.

I couldn’t use it and he got very upset when I went to Kerouac. There was no choice. But we stayed in contact and he came up to Mabou. He had a hard life when he got older. He liked big cars. He would say, “Okay now, I’m going to photograph, so take the car away. Don’t come near me.” He didn’t want anybody to watch him photograph. I could understand. I would be the same. I don’t want anyone carrying my camera around.

The Paris book includes a photograph of a palm reader’s station and it shows a poster with Les Lignes de la Main written above a drawn hand, and underneath are written the words “sciences et mystères.” Did that image become the title and the icon for the cover of The Lines of My Hand, the book you would do some 15 years later?

It probably came from that. June drew the hand for me. I also like the cover photograph of the Paris book. It’s a movie poster decorating the outside of a pissoir. ❚