Pivotal Moments

Shirin Neshat and the Art of Tragic Euphoria

A sense of mysticism pervades all of Shirin Neshat’s work, in the gentlest but most persistent manner. It’s evident in her person—this small, delicate as a bird, formidable individual who enchants and engages an audience by making her ethical rigour very clear. As the 2017 Dasha Shenkman Lecturer at the University of Guelph this spring, she stood at the podium and presented, in her light and musical voice, images from her many iconic bodies of work. Iconic in the sense of their visually apparent binaries; their distinct black and white palette; the choreographed movements that seem to represent ritual and cultural understanding in a structured religious sense, but not specific or delimited; and large sculptural gestures set against essential geographies: sky and sea and vast horizons. She talked about migrating populations and oppression and freedom, about exile and home, about violence and peace and courage and the necessity for the imagination to flourish and out of it to make art that speaks to all the conditions of being human.

In the interview that follows she spoke about her process of artmaking, saying that the challenge for her is to find a balance between what she identifies as realistic material—that is, what she sees in the world that has a profound impact on her—and her transforming it into art. It’s an interesting necessity she defines here—the real into something else, which could suggest a state of unreality, or the unreal (which is art) but which, for Neshat, is real. It’s the achievement that makes the world actual. So it is for artists. She has the actor who plays legendary Egyptian singer Oum Kulthum tell the filmmaker who is a surrogate for Neshat herself in her just-completed film Looking for Oum Kulthum, “You know, I really like your fire, I like what’s eating you up. The craziness—all the things you are questioning about your films and your life—is the artist in you,” Kulthum tells Mitra.

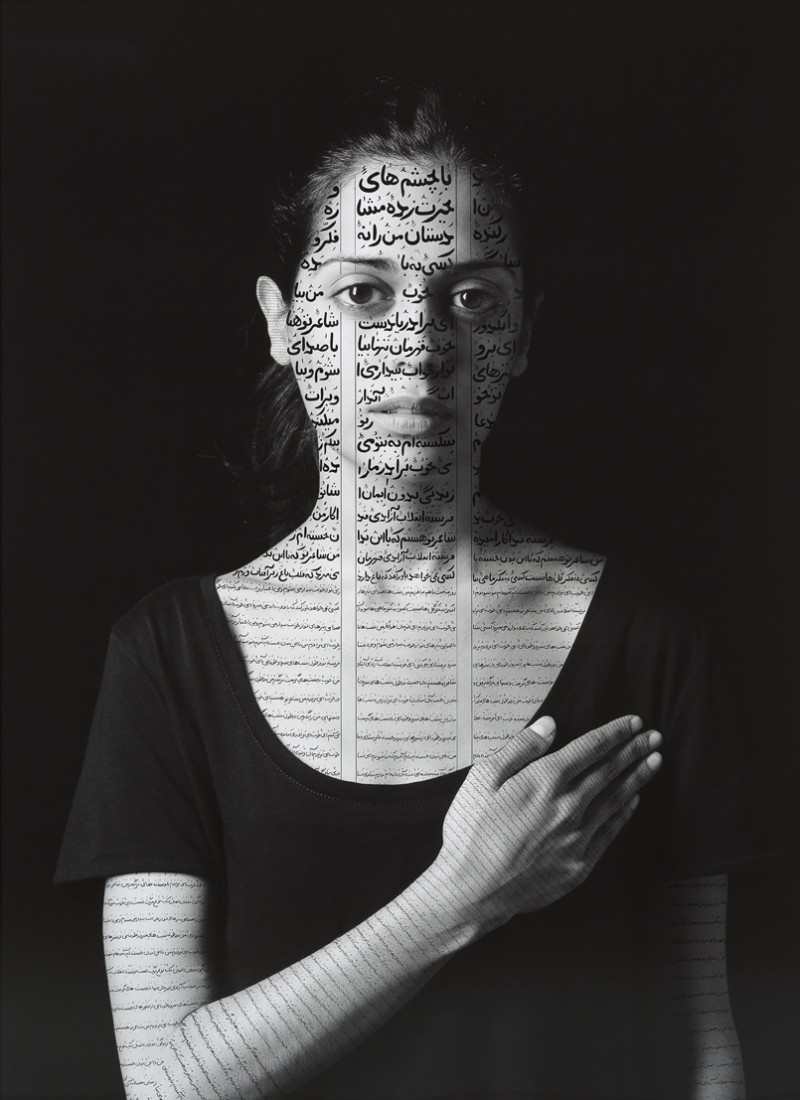

Shirin Neshat, Roja (Patriots), from “The Book of Kings” series, 2012, ink on LE silver gelatin print, 60x45 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels © Shirin Neshat.

Neshat described it as needing to complicate things in order to keep a balance between what’s real and what’s not. It’s her saying, “So what I have left is the world,” which strikes me as a statement of some mysticism, coming from some other place perhaps, and then into the world, so that the art she makes is her balance between here and there.

Books and poetry often are sources and points of departure for Neshat, and here, too, is the push and pull that seeks balance but not a fixed equilibrium: poetry and beauty retaining their power only when paired with pain and tragedy. It’s the cold steel of the gun’s muzzle under the ear and nestled against the warm cheek of a beautiful woman from Neshat’s “Women of Allah” series of photographs or Canadian poet Robert Kroetsch’s “Love is a beak in the warm flesh” from Seed Catalogue. “It juxtaposes disturbance, pain and suffering next to beauty, poetry and ecstatic harmony,” Neshat told Border Crossings, finding exhilaration in this condition, the exhilaration of melancholy, which comes from the tradition of Iranian mysticism and is a desired and productive state. It obliges contemplation and reflection, which are finally generative.

Another prevailing state, one that asserts itself with some consistency in Neshat’s work, emerges from the often unresolvable condition of exile. Seeking after home is universal; it’s the longing for security that impels us all, whether notional or actual and geographic—a state of mind, or the denial of statehood. Neshat had just completed a trilogy of videos: Illusions and Mirrors, 2013 with Natalie Portman, based on what she describes as the logic of dreams, a logic to which she subscribes, and Roja and Sarah, 2016. These are related to Iran and her own experience. Roja speaks to an enforced distance from Iran, her home, her “motherland,” as she describes it, and Sarah, too, finds the protagonist looking for and finding herself. The resolution of the search carries poignancy as well as a sense of completion, with Sarah finding herself at home finally, in death.

In 2017, Shirin Neshat has produced, among much else, two major, significant, large and very public works: the film Looking for Oum Kulthum, and a commission by Conductor Riccardo Muti to conceive and direct a new production of Verdi’s opera Aida for this summer’s Salzburg Festival.

As in everything she does, Neshat will imbue this production with her unwavering ethical rigour. She describes her planned production as a rereading of Aida where the audience will be obliged to think anew about who is victim and who is victor. Ancient Egypt, as she will present it, will be a hybrid. Hybridity has to be the binocular lenses through which we now look at the world in its conflicted state. Neshat does this doubling in the art she brings to us.

.SN343_1100_474_90.jpg)

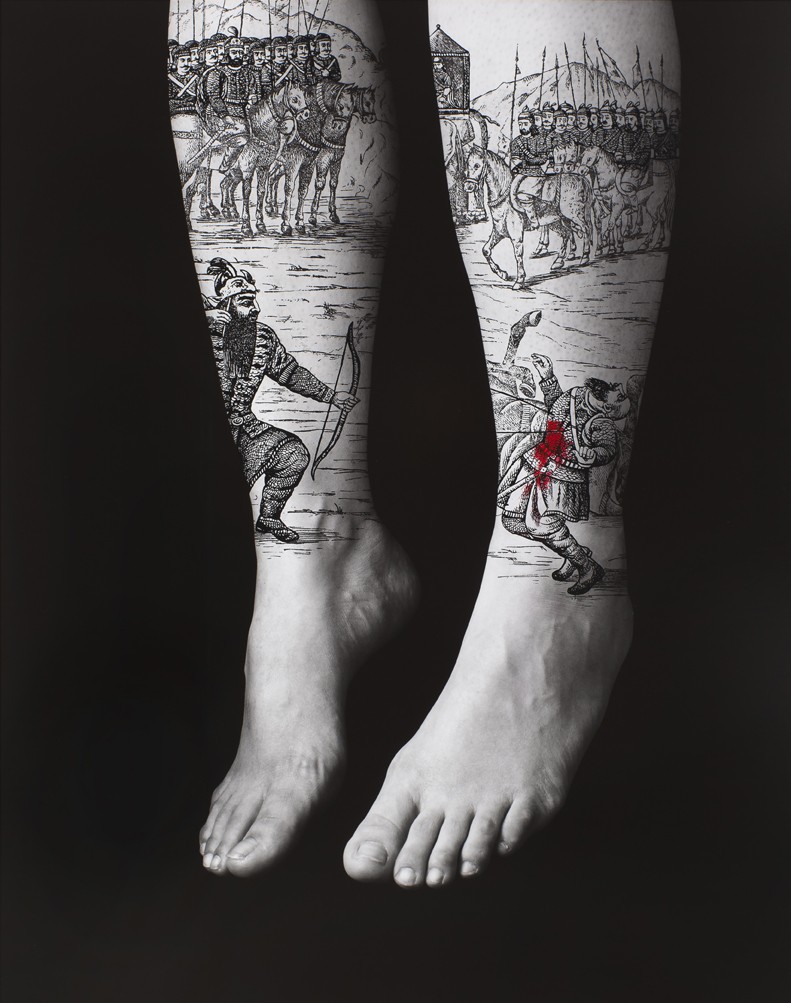

Untitled, from Roja series, 2016, silver gelatin print, 40x92.75 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels © Shirin Neshat.

Shirin Neshat’s major exhibition “The Home of My Eyes” is presented from May 10 to October 31 at the Museo Correr in the Piazza San Marco as part of the 57th Venice Biennale; “Shirin Neshat: Dreamers” opens at the Gladstone Gallery in New York on May 19 and runs until June 17.

The interview with Shirin Neshat that follows was conducted by phone to her Brooklyn studio on April 2, 2017.

Border Crossings: We spoke before the last three bodies of photographic portraiture were made, so let me go back and ask about the origins of “The Book of Kings.”

Shirin Neshat: It came after Women Without Men, when I had been involved in cinema for years and hadn’t done any black and white photography and calligraphy. I remember very clearly how welcoming was the idea of being back in the studio and making work that was more intimate and that involved my hands. If the topic of “Women of Allah” evolved around the concept of martyrdom, and the revolutionary fervor that developed in Iran before and prior to the Islamic revolution of 1979, “The Book of Kings” series tried to capture the next pivotal political moment of Iranian history in contemporary times, the popular uprising that occurred immediately after the 2009 election in Iran and later led to the Arab Spring. This uprising united Iranians who had been divided both inside and outside, in their common call for democracy. When I look back I realize that the Green Movement in 2009 was the first time that I became an activist. Before, I had turned my back on any direct political activity, and suddenly I found myself active in protests, in collecting petitions and in hunger strikes.

Divine Rebellion, from “The Book of Kings” series, 2012, acrylic on LE silver gelatin print, 62x49 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels © Shirin Neshat.

What was it about the Green Movement that provoked you to get involved in a more direct way?

It was the most pivotal event in Iran since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. There was euphoria that the people of Iran could talk back to the fanatics and wouldn’t allow their kind of oppressive environment to continue. Of course, it didn’t succeed but it created this amazing energy. I thought my “Book of Kings” captured that spirit of activism and patriotism, which was so different from the time of “Women of Allah”. There, it was all about fanaticism and men and women being brainwashed and very submissive to their religion. Here, you had a lot of very young, modern and educated people who were not interested in religion at all. In fact, if you look at them and then at the images of “Women of Allah,” you can see the change in Iranian society. At the time, I was preparing a show for Barbara Gladstone and I decided to create this large body of work that captured the dynamic of the fanatics who hold the power, the martyrs and the patriots who are the activists, and then the people who are witnesses or bystanders. I started photographing many young Iranian activists whom I met in New York and also some Arabic friends who were activists for their own countries, and created a photo-installation that included 65 images.

But you also took inspiration from a book, this time the 10th-century epic poem by Ferdowsi, called The Book of Kings.

Yes. The book, the Shahnameh, tells the mythological past of Iran from the creation of the world to the Arab conquest. Ferdowsi, by the way, is known to have saved the Farsi language during the Arab conquest, so he is cherished to this day. His stories were about the concept of martyrdom and patriotism, about people who were beheaded and who sacrificed themselves for their country. My copy of the book had these black and white illustrations, but I ended up painting over the bodies of the villains. So this book in many ways has this contemporary relevance to the Iranian situation, but it also referenced a literature that belongs to ancient times. Here, history seems to repeat itself in showing how the Iranian people through time have continued to revolt against all forms of dictatorship, including the Arab conquest and the Islamists. During this time I was going to Egypt a lot because I was doing research for the Oum Kulthum film. I happened to be there during some of the more pivotal moments in Tahrir Square and I found myself in the middle of a revolution that went from Tunisia to Egypt to Algeria and all over the Middle East. But that, too, was defeated. So I devoted this whole body of work not just to Iran but to the Arab Spring. Then I was approached by the Rauschenberg Foundation to do a project and the profits would go to a humanitarian cause. I proposed to go to Cairo in the aftermath of the Arab Spring to capture the human dimension of the people who had lost their children and the damage the revolution had done, now that the euphoria was over.

But there is a difference between the subjects of the portraits here and the people who turned up in the earlier series.

Yes. Whereas “The Book of Kings” was intentionally about the faces of youth, I wanted the “Our House Is on Fire” series to be about older people who were really bystanders and, even though they didn’t actually fight for the revolution, they experienced the tragedy. So I photographed 50 very old, extremely poor people living close to Tahrir Square. I had a translator who spoke to them about their lives and their experience of the revolution, about who they had lost, and that conversation was eventually written on their faces. So in a way, “Our House Is on Fire” is the closing chapter of The Book of Kings.

The title for “Our House Is on Fire” also comes from a book of poetry, this time by a contemporary Iranian poet, but this work seems to be the closest you have ever come to traditional documentary.

This is very true. First of all, it was a job, almost like a commission, but it also involved my going to real people who had real experience and having extensive conversations. I paid them with the help of the Rauschenberg Foundation. But you’re right, it is not purely fiction; it’s more like the narration of something that is truthful and that really happened. These people wept as they told their stories. I was accused by some people of capturing suffering to make art, but for me it was an act of recording history. It was done for a project supporting humanitarian causes, not for profit. I just felt it was important.

.Sarah_Out.00_11_08_14.Stil_copy_492_276_90.jpg)

Sarah, 2016, production still. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels © Shirin Neshat.

Your mother was Azerbaijani. So in “The Home of My Eyes,” when you ask people to describe what “home” means, you are inquiring into a subject close to your own heart. You have said about your work that “the place of home is absent but the search for home is totally there.”

Exactly. Even though I am outside Iranian society, when I embrace a new culture that is not Iranian, I bring myself into that culture and try to look for meaning there. Also Azerbaijan was a part of Iran until the middle of the 19th century, and we share a religious, cultural and traditional background. We were one nation. Many of us still speak the same language and many Iranian people constantly go to Baku. Also, there is an Iranian poet called Nezami, who, at some point in ancient times, migrated to Azerbaijan and is now regarded as both Azari and Iranian. So we have this very interesting mixed background. Religion is not a problem there. In fact, they have a lot of freedom about being religious or not, which is something that unfortunately we didn’t have in Iran.

There are photographers, I’m thinking of August Sander in Germany and Richard Avedon in the American West, who set out to document a culture or a region. You are less systematic, but you end up doing something of the same thing.

For me, the challenge is how to find a balance between this realistic material and the things that have a profound impact on me, and then to figure out how to stylize it and turn it into art. Whether it is “The Book of Kings” that relates to Iranian society, or even the simple hand gestures in “The Home of My Eyes” that referenced Christian paintings, I feel like I always have to complicate things and keep a balance between what is real and what is not. That ultimately stops it from being pure documentary and also brings in my artistic signature. The history of art is a story of artists going to other places: Gauguin to Tahiti; Eisenstein to Mexico. So what I have left is the world.

It’s interesting that you would use the phrase “artistic signature.” One of the things that functions in all three bodies of work is evidence of your direct signature in handwritten texts.

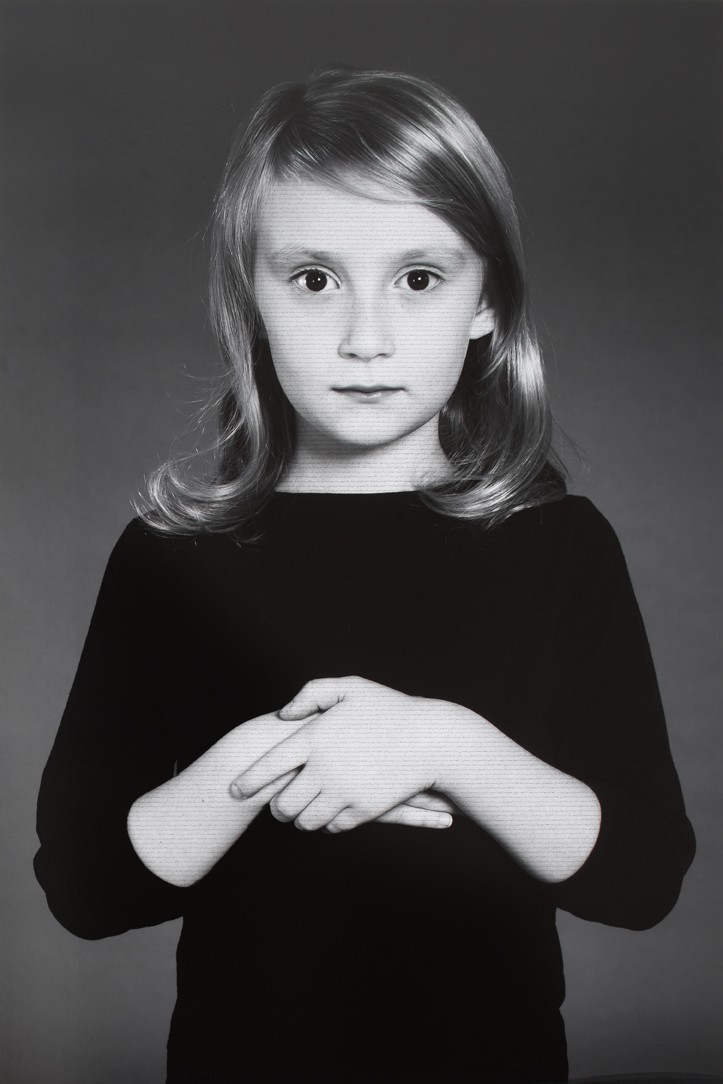

You haven’t seen the latest photographs in my exhibition coming up at Barbara Gladstone. I have taken pictures of people from upstate New York, a rural kind of Americans who exist a world apart from New York. They are some of the people you see in the theatre in Roja. I tried a thousand different ways to incorporate writing on their faces and it looked like I was forcing my signature onto something that was not allowing it. The people from Egypt and Azerbaijan were culturally closer to me because Azari and Farsi are similar. But when it came to the Americans, it appeared like a market strategy and I didn’t like it at all. So I approached the characterizations very surrealistically; I used a technical thing on the camera to make their faces go white and blurry. It was as if I couldn’t see through them very well. All the images are softly demonic and strongly mystical. I like that because it was my way of looking at people I don’t completely understand. I think they would feel the same about me. So this is where the handwriting stopped. People might not even recognize these photographs as my work.

Roja, 2016, production still. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels © Shirin Neshat.

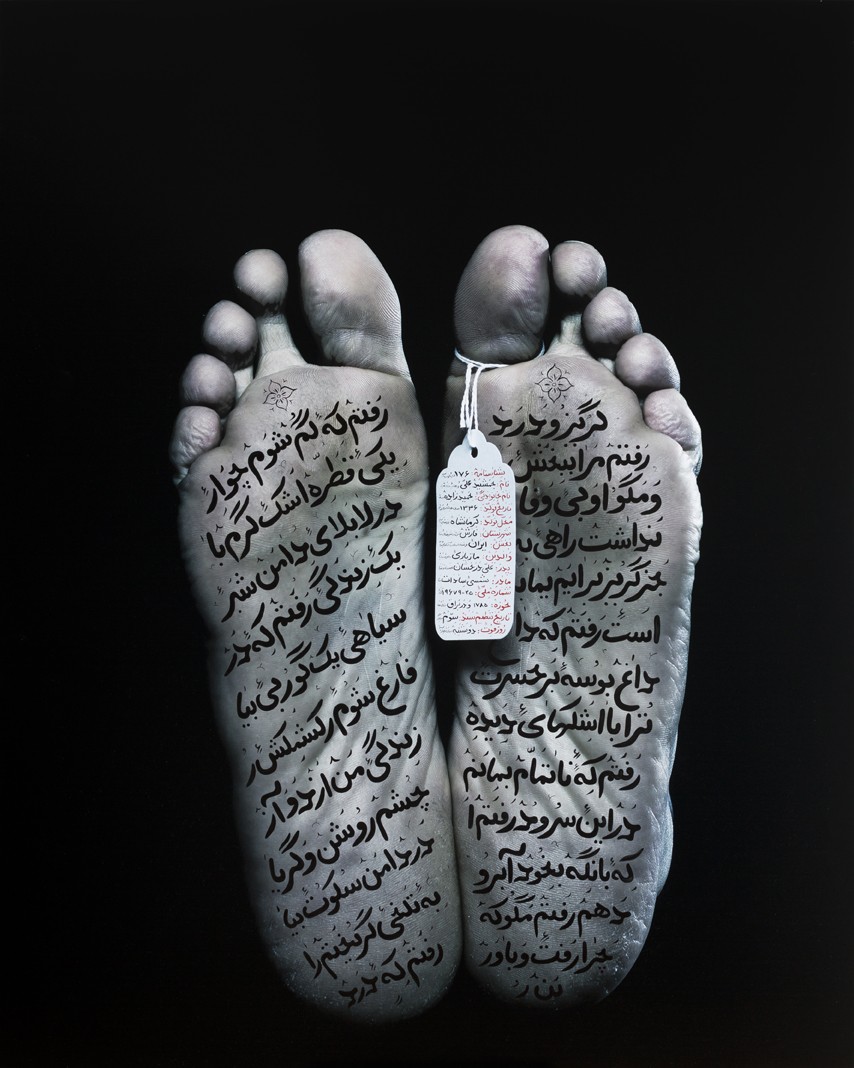

In the three previous bodies of work the images, which are quite formal, have an almost sculptural presence. But there are other startling images; I’m thinking of the photographs of feet with tags on their toes.

The thing that struck me about the Arab Spring, and even in the Green Movement, was how this incredible sense of euphoria ended in tragedy, violence, death and genocide. At first the Muslim Brotherhood was active and loved by the people in Tahrir Square, but when Morsi became popular and started to take advantage of this new democracy, then the Brotherhood was once again targeted, particularly by the military. So they just bombed the hell out of them inside a mosque. Some of the most devastating images I saw were rows of dead bodies wearing tags. I returned to a well-known picture of mine from the “Women of Allah” series called Allegiance with Wakefulness, which depicted two feet with a gun in between. So the images you are referring to played off one of my own images, but instead of a weapon suggesting militancy, we are faced with death. All that remains of this bravery and patriotism is a small tag that tells where they were born, their name and their mother’s name. I felt this extreme sense of despair at how this euphoric activism among people who loved their country with such passion was reduced to a little tag between their two feet. I wanted to capture that sense of tragedy, which is what the original Book of Kings does in a mythological way.

Is there something transgressive about showing the bottom of the feet in Islamic culture?

Yes. The bottom of the foot is the absolute lowest and the worst part of the human body, the part you wash before you pray. Muslims have to cover their bodies, so, particularly with the women, I often put the most sacred poetry on the bottom of the feet. The most ugly then becomes the most precious. I spend hours and hours writing beautiful calligraphy on the part of the body that is usually trashed.

You tend to use poetry in both a lyric and subversive way?

Looking for Oum Kulthum, 2017, production stills.

I think any idea of beauty or poetry is powerful only in harmony with pain, tragedy and suffering. I don’t think I have ever made a single photograph or a frame in a film that has been aestheticized and beautiful without some suggestion of horror. Think of the anorexic woman bleeding as she washes herself in this Orientalist image of a bathhouse in “Women Without Men,” or in the “Women of Allah” series, the gun is held by a very seductive woman. It juxtaposes disturbance, pain and suffering next to beauty, poetry and ecstatic harmony. The essence of reality is that the good and bad always coexist. I think some of my weakest works are the ones that are overstated. When I don’t manage the balance I get too much beauty or too much suffering.

So does the battle between the poetic and mystical and the fanatic and doctrinaire ever get won, or do you end up being an aesthetic Manichean, where you simply present the two sides as if they were equal in power?

The best way to explain the melancholic mood in my work is that it comes from the tradition of Iranian mysticism. I always wondered why we listen to music that makes us cry, and why Iranian people have this obsession with extremely dark poetry. But it’s not about sadness; it is about reflection, about a melancholy that somehow becomes exhilarating and fulfilling. We all talk about the greatest mystics, Hafiz and Saadi and Khayam, and much of what they say is extremely melancholic but also reflective on a more existential level. Think about the way Rumi writes about life and death and love in his poetry, or the songs of Oum Kulthum, or the films of Kiarostami. It is all about issues and ways to transcend time and place, and to achieve an expression that is purely philosophical and existential.

Looking for Oum Kulthum, 2017, production stills.

Let’s go to the adventure you set out on when you decided to do a feature-length film on the legendary Oum Kulthum. Where did you get the idea to make the film?

I remember at some point of my career, after participating in multiple international exhibitions, I felt a certain type of exhaustion from the art world and felt like moving on to a new medium. I started by optioning a beautiful, surrealistic book by the Albanian writer Ishmail Kadare, which I thought would be wonderful to turn into a film. But by coincidence I met Bahram Kiarostami, the Iranian director, and Abbass Kiarostami’s son, who lives in Iran and is a documentary filmmaker, at a film festival in Amsterdam. One day late at night we were at the hotel listening to Arabic music, including Fairouz, a Lebanese singer, and Oum Kulthum; Bahram turned toward me and said: “You have to make a film about Oum Kulthum.” My immediate response was, “Are you out of your mind? I’m not even Arabic!” His response was, “All your work is about women and music, and Oum Kulthum is such a legend, you should really think about it.” As soon as I got back to New York I went to a bookstore to look for biographies about her and, sadly, there is only one great book by a musicologist called The Voice of Egypt. There isn’t much written in English and so I started my own massive research. I realized what a fascinating woman she was and slowly started to think, “Maybe I could make a film about her.” Originally, I was thinking about a biopic, so this led to finding an Egyptian assistant and going to Cairo to visit her family, doing more research and conducting interviews. Gradually, something that was pure fantasy became reality.

Did you have a sense when you started that it would be as completely absorbing as it turned out to be?

I had no idea what I was getting into because we’re not talking about an artist but an iconic artist who is the beloved symbol of the Arab world. I got a lot of resistance because I’m not Arab. Producers came in and promised the world and then disappeared. There were lots of setbacks and so much disillusionment that I thought this project was going to die. But everything changed in the fourth year because of Jean-Claude Carriere, who was the scriptwriter for Bunuel’s major films. I met with him in Paris to get his advice and showed him the script and he said, “Shirin, forget it. Don’t make a biopic. That is the most boring way you can approach it. Think about why you are obsessed with this woman. Make it personal.” That was a turning point. It still took another three or four years to reshape the script and secure the partners. We had a hard time raising money, and I even sold my own work to help the film. It was one battle after the other, both artistically and production-wise, but we finally found the right match and just enough money and we got it going.

You said that in developing the script, “I allowed myself to be crazy for two years.” Was part of the craziness realizing that you could personalize the film by letting in the dream?

Yes. I think at a certain point in your career you wonder about the degree of risk you can take. How crazy can you get? I remember days when I sat with the script and gave myself absolute freedom to imagine everything. And the more crazy I got, the more people said it was the right direction. Of course, later we had to be careful with the plot and I came back to reality, but what had become clear was that the film had to be turned into my language and that it was impossible to hand it over to someone else.

Anna, from “The Home of My Eyes” series, 2015, silver gelatin print and ink, 60 x 40 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels. © Shirin Neshat.

You talked about the complex tapestry of this film, and it seems to me that the complexity comes through the various layers with which you’re dealing. This is the first time that you have actually used archival footage; you’re using actors who are playing historical figures like Nasser and King Farouk; you have an actress playing Oum Kulthum at different periods of her life; and you have the dream sequences.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the film but also the greatest challenge has been to keep it accessible and still have the dream sequences work. We have four layers: the actual film that I’m shooting; the production, which is the story of this filmmaker herself and her own trajectory as a person; then dream and imagination scenes that have their own logic and reality; and then you have the archival footage. So the question is, how can we write and edit in such a way that the audience wouldn’t get overly confused? For example, we are now editing with different textures and colours. I am going to Austria tomorrow to decide, along with the cinematographer, how the different layers will have their own look and even sound. We have different music and sound for the actual film that she is shooting, as opposed to the scenes where the director is by herself and very sorrowful in her room, or the dream sequence, which is really eerie and almost silent. We have been thinking about how to create a signature for the different layers. So far the transitions have been most difficult.

I assume that the filmmaker is a surrogate for you. One of the ways you work the archival footage into the film is by having Mitra and her crew watch it in a screening room. It allows you to amplify the meta-dimensions of the film.

Exactly. I’m actually using my research as Mitra’s research and inspiration. In the scene you mention she is looking at footage of King Farouk and she ends up with images of the Feminist Protest of 1919, which we then integrate into the film she is shooting. You’ll see exactly how she borrowed the costumes and scenes and set-ups for her film. I think in the end this film will be cinematically unique because of the way we integrate all these different layers.

Gizbasti, from “The Home of My Eyes” series, 2015, silver gelatin print and ink, 60 x 40 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels. © Shirin Neshat.

In the midst of the complexity of your feature-length film, you also make Roja and Sarah. Was that a way of escaping the complicated narrative you were involved in with Looking for Oum Kulthum?

Actually, it started with the video I made with Natalie Portman in 2013. I had to come up with a narrative that had nothing to do with Iran and being Muslim. I couldn’t just use Natalie Portman as a statue like I do with a lot of the people in my films, so I decided to make a film based on the logic of dreams. I’ve written down my dreams over the years and I find them very compelling. After the Portman film, which is called Illusions and Mirrors, I thought, “Why not make two more that could be considered a trilogy?” The difference is that Sarah and Roja are related to Iran and to my own experience.

Rahim, from “Our House Is on Fire” series, 2013, digital C-print and ink, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels. © Shirin Neshat.

The most striking thing about Roja, and I’m speaking here about the way that it propels narrative, is the fury of the verbal attack the man makes on Roja, calling her “deceitful, cunning and manipulative,” and referring to her “hideous hateful heart.” Who is that guy and where does that venom come from?

We were casting in upstate New York and we wanted people from the region who were not professional actors who could both sing and perform. I chose this guy and explained that he had to come up with a song that would move a woman to tears, but that he also had to be capable of being aggressive to the point of violence. He had a regular job but at night he played guitar in a restaurant. He loved art and had wanted to be an actor but had never had the chance. What you saw was complete improvisation. The guy obviously took instructions very well; he even did research and found the right song. It’s a 1967 hit by The Seekers called “The Carnival Is Over.”

I know what Roja is running from but I wonder what she is running towards. That meeting with the older woman, who I assumed was a very determined mother character, is an encounter of a different kind. Why does that woman reject Roja in the way that she does?

As I said, this was based on my own dream experience. My mother, who has played a very important role in my life, is my last attachment to Iran, but what was really interesting was that the mother who is supposed to be a protective and loving figure ends up being a monster. When Roja eventually reaches her—and this is exactly how it happened in the dream—the mother presses on her chest and Roja flies back into the sky. I think my insecurity about my country is also about my 85-year-old mother. I have a desperate nostalgia and love for Iran and want to be a part of it, but at the same time it is pushing me away. This is why I say my mother is like the country. Without being melodramatic, I think the only thing that remains for me in a homeland is the motherland.

Everything in Roja is dramatic: the architecture of the building, the histrionics of the actor on stage and the dramatic encounter between Roja and her mother. You have exploited that theatrical quality quite effectively in your work.

Stage set models for Aida. Production Designer: Christian Schmidt. Costume Drawings. Costume Designer: Tatyana Van Walsum.

In a short video I am always worried about being overly theatrical and too obvious and placing too much significance in a particular thing. My most successful videos are the ones that keep that level of theatricality in the right balance. It is hard for me to measure when I am making the videos. There was a lot of playing with opposites, which I do very often, and everything had to be exaggerated. So the building had to be over-the-top, and we ended up in the coal mines of Pennsylvania for the landscape. I wanted something extremely simple, like a chalk drawing. So we worked hard on this theatricality and on creating two physically opposite landscapes.

Was Sarah also based on a dream?

It was, but not one of mine. It was inspired by a Kurosawa film called Dreams, which is a number of short films that make up a very beautiful long film. All of them were haunting and a little nightmarish, particularly the one about the entrapment of a woman inside an environment where there is the reminiscence of genocide. Basically, she is not sure whether she is dead or alive.

Taken together, the soldiers marching through the forest, followed by the black-clothed women who are praying and carrying incense burners, pose a threat because you don’t know what Sarah is running up against.

We wanted to be evasive, and the identity of the soldiers was not made very clear, but they were at war and there were hints of genocide. The women, for me, were like mourners. What became apparent was this overwhelming and inescapable sense of mortality and death. Sarah follows the women to see if she can find a way out, but what she sees at the end is herself, floating in the water.

The ending is intriguing because when she is submerged, I didn’t know whether to read it ambiguously or not. It reminds me of the women setting out in Rapture; they could be escaping to freedom or they could be dooming themselves to a watery death. At the end Sarah’s eyes are closed, her lips are slightly parted and her body is eroticized because of her wet, filmy top. It looks like an image of acceptance rather than fear.

Stage set models for Aida. Production Designer: Christian Schmidt. Costume Drawings. Costume Designer: Tatyana Van Walsum.

She does go down with a smile on her face. We tried to end Roja on a positive note through the freedom of her dream-state flight. Even in Illusions and Mirrors Natalie Portman goes to the darkest and most frightening point in this haunted house, only to come out to lightness and clarity. It’s always a question of going deep down to find yourself. It’s hard to defend these narratives in a realistic way because they weren’t meant to be read like that. But I did mean for every one of them to have a sense of resolution.

You’re not naïve by any means, but it seems to me that you are somehow hopeful.

I think that is my nature. Between the two of us, my husband, Shoja, says I am always the optimist. I am a fighter and every time I fall, or things are less than desirable, I tend to pick myself up. I have been a survivor and I’ve been alone in dealing with a lot of changes in my life, first of all as a young woman here and then going through different family situations. So to this day when I have to go back to myself, I always try to be optimistic. The characters I portray in my films, or in the photographs, seem to take off from my personality.

A lot of artists have shifted into film: Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Matthew Barney, Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo—I could compile a long list. When you make that move, do you have to locate your work along a spectrum that chooses between art and cinema? You have said on many occasions that you think as an artist rather than a cinema artist.

It’s funny but two days ago I was working with this woman at the Metropolitan Opera who is my stage director. I think she has been at the Met for 25 years. We were going through the different acts and scenes of Aida and she was always looking to me for answers. Here is a woman who can read music and is a singer, and she is looking to someone who can do neither of those things. I found myself responding very naturally and saying, “Let’s do this and let’s do that.” I realized that once you put yourself at the mercy of another language, your artistic response is automatic. It’s like your intuitive judgment plays itself out. At first you have a tendency to say, “I can’t do this,” but when faced with a stage, the actors and the music, I think, “Okay, how would I want to move these people on the stage right now; what would be more beautiful?” and the answer is not that complicated. As artists we are sometimes too afraid, and the reality is that our minds work by responding to things as they come our way. We think we are good at only one thing, but whatever approach we have in terms of our creative forms, we can apply to anything. It could be flower decoration; it could be the way we make a building; it could be to opera, cinema or photography. Next to the people I’m working with, I always feel I’m underprepared and I have to work more than they do, but then I recognize I have overprepared. I see the fear and the anxiety that live inside of me, but at the same time that anxiety is positive because it forces me to trust myself and my instincts.

So with Aida, you have said that you have taken liberties to change the power dynamics and the fanaticism in the original opera. How liberal have you been?

Stage set models for Aida. Production Designer: Christian Schmidt. Costume Drawings. Costume Designer: Tatyana Van Walsum.

Two things don’t change in opera: the music and the script. What you can change is the interpretation. While Aida is very popular in the West, it is extremely problematic for the Middle East. A number of intellectuals, including Edward Said, have written extensively about Aida, dismissing its Orientalist look into Middle Eastern culture. As I tried to envision my interpretation of Verdi’s Aida, many questions came up. So what I’ve done is to give it some contemporary relevance by shifting around the identity of who is the superpower and who is the victim. Also, the inspiration for my conception of the program comes from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, so it is extremely futuristic but also very ancient. Ancient Egypt in my program is a hybrid, which you see in the costumes more than anything. The other significant change is that the priests become a large group that represents the really horrible part of all religious fanatics. I also used Aida and the Ethiopians to make some subtle references to refugees from Africa and the Middle East.

In Metropolis the sets are expressionist. Does your set design look like that?

We pay respect to the monumentality of ancient Egyptian culture and architecture but keep it very minimal. I’m also including a video. There are four acts in the opera and so there will be one three- to four-minutes-long video in each act. But what is important is that the stage rotates and every rotation gives you a completely different point of view, like a Richard Serra sculpture. It becomes a different animal when you see it from different angles.

At the beginning of the opera, the “Triumphal March” affords an opportunity to display the victorious army combined with some serious choreography.

One of the problems is that Verdi created this quasi-Oriental ballet, which we are not doing. Our choreography is more ritualistic. We have only eight dancers, as well as the chorus and the extras, so there will be very simple movements that even the chorus can do. The choreographer specializes in working with people who are not dancers. I want even the body movements to be stylized, so we’re incorporating Sufi dances, ritualistic dances, Polynesian dances and steps from Pina Bausch. Everything is a hybrid.

Ten years ago you said that your own work “has a very sharp knife but in a quiet way.” Do you still think of your work as sharp but quiet?

Stage set models for Aida. Production Designer: Christian Schmidt. Costume Drawings. Costume Designer: Tatyana Van Walsum.

Yes. We all agree, me more than anyone, that the last thing we want to do is make a political and didactic piece out of Aida. We don’t want to be doing propaganda. But the “Triumphal March” is a celebration of invasion and killing and bringing out slaves. That’s not something to be celebrated and I won’t participate in anything supporting that. I’m going to turn it around. So the audience will have to catch the more subversive intervention of not allowing such a thing to slide by, that killing and stealing and taking slaves are not okay.

Is quiet subversion more effective than the noisy variety?

For sure. People come for the love of the music, and if I can instill some meaningful message that they hadn’t thought about, then even better. I don’t know how people from the Middle East will respond, but I certainly don’t want to be heavy-handed. I can name artists from the Arab world who sometimes go overboard in terms of this whole identity thing. I always find it best when you are allegorical or as minimal as possible; otherwise it is just too much like preaching. ❚