I Like the World and the World Likes Me

An Interview with Dana Schutz

Dana Schutz exhibits at Petzel Gallery Sept. 10 - Oct. 24, 2015 and Musée d’art Contemporain de Montréal Oct. 17 - Jan. 10.

When painter Dana Schutz says, “The only thing you can do is to make work you find interesting and important,” I believe her. She told us this in the interview which follows. By important she means necessary, essential, urgent. And somehow, once made—rational and anticipated, right, as inhabiters of the world. She said it too in conversation with curator Chrissie Iles, in 2014, in Dana Schutz Demo (Walther König, Cologne). “I wanted to be painting subjects that did not exist or could not be painted from observation or photographed…to make something that felt like it had some kind of consequence.”

Girl on a Horse, 2013, oil on canvas, 108 x 62 inches. All images: courtesy the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York.

“No ideas but in things” is the line and conviction that runs through American poet William Carlos Williams’s five book poem Paterson, published separately as books between 1946 and 1958. A language that was intended to parallel, to be as material, substantial and true as its subject. Schutz’s paintings are real things, built subjects sometimes surprising her with their own volition and once done—there and actual. That’s why the viewer is important, as is the space of seeing; eye contact is a real thing which happens in an ocular confrontation between the painting and the viewer. “If you can see something then it exists as fact,” she tells us, insisting on space and time.

The horse bolting out of the starting gate with the painted velocity of futurist Umberto Boccioni finds you stopped in its path in Girl on a Horse, 2013, because you are locked in direct eye contact with the rider on its back, which was Schutz’s intention. Not that you are mowed down, but that contact has been made—her rider to your seeing.

“I want the paintings to be singular and alive,” she says, and the “God Paintings,” 2013, are that. All of them are singular, and then inevitable. It’s what she admires in the work of American artist Philip Guston. His sense of the hypothetical, of speculation which is individual, is the “what if…” she wants as a prod to making paintings. What if God were…? Inside her head she goes, inside memory, inside her projections, inside the potential of painting, inside the American psyche—pushing at the barely containing edges of the canvas. She asks, “How does this thing exist in space?” And she tells us about the two kinds of space she recognizes: the deep space of the painting which is the picture, the representation, and the actual space of the rectangle that it’s on. Like William Carlos Williams she says she “like[s] the world, I like that things have weight, that objects affect other objects in a kind of physical and sometimes practical way.” Contiguous, necessary, important.

Girl on a Horse, 2014, charcoal on paper, 84 x 48.2 inches.

Some kind of delicate balance is also necessary. Think of Schutz’s paintings, the “Self Eaters,” 2003, and later the Face Eater, from 2004. Critics have seen the paintings, with their self-absorption—where painting becomes its own subject—as ideally allegorical and solipsistically complete. But Schutz intends the consuming to be generative, to lead or carry on, and the devouring selves are also remaking their beings out of their own stuff. I’m reminded of the symmetry in William Butler Yeats’s poem “A Prayer for My Daughter,” where he comes to understand that seeking equanimity, the soul finally recognizes it is “self-delighting, self-appeasing, self-affrighting.”

Colour speaks volumes in Schutz’s paintings; in the drawings the sound is reduced and the narrative elements are less complex. At the same time, through this reduction they have a structural clarity that makes them rich. There’s nothing missing from Bed Parts, 2014, where you see the scramble and the potential, the disassembly and the coming together of a bed with its jumble and vulnerability. The chaos and the creation, arms and legs protruding or locking, and there’s a big flat-footed nod to Picasso on the bed’s horizontal plane, up-ended and made vertical. The drawing, Flossing, 2014, is a thoroughly satisfying and complete composition with its classical symmetry, and it is hilarious. The flossing figure holds an end of the dental floss taut in each fist. Though naked, he is dapper. It could be his matinee-idol slicked hair and for heaven’s sake, he is flossing Elaine de Kooning’s teeth. In Willem de Kooning’s Woman1, 1950–1952, the woman who is arguably his wife shows the same row of teeth, and the same breasts, as large as his pecs or his as large as hers. She is without an erection, but both have large eyes, each of them a formidable figure. Dana Schutz told us that particular drawing reminded her of sex and death. Possibly de Kooning thought the same.

Schutz wants her work to be singular, to claim its own personality, to offer surprise in its encounter, to be interesting and important. Yes.

This interview was conducted by phone with Dana Schutz at her Brooklyn studio on January 25, 2015.

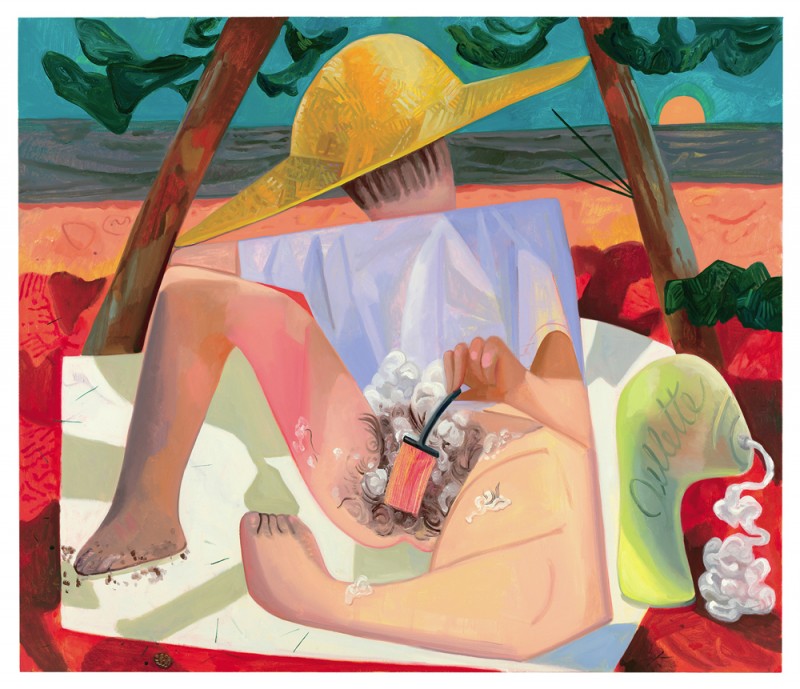

Swimming, Smoking, Crying, 2009, oil on canvas, 45 x 48 inches.

Border Crossings: Your mother was an art teacher, which makes me wonder if art was a part of your upbringing.

Dana Schutz: My mom was really great at portraits, but she never pressured me. My aunts were also artists and I would see some of their paintings but I didn’t know I wanted to be an artist until later.

You did make some pretty decisive decisions. You were only 23 when you went to Norwich in England and then you attended the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture. Those seem the moves of someone who knew she was going to be an artist.

That didn’t happen until I was 15, at which point I was very decisive. I ended up going to the Cleveland Institute of Art after that. It was the only thing I wanted to do. I was making a little bit of sculpture in undergrad but mostly I was painting.

Did your work already have a signature style at Cleveland?

I don’t know if there was a signature style but I do know it wasn’t very good. I was making a lot of it, trying things out and wrestling with ideas of representation, the gesture, and wondering if you could make a painting “painterly.” The question was could you have facture in your painting and not have it be coded? We were talking about the way gesture had been used in art history and some of the subjects I was painting tended to be slightly self-reflexive. I was making paintings of terrariums, which was itself a contained painting space. Some of them would have big swells of oil paint just below the surface, so the picture would bulge out in certain areas. Then some were more minimalist, like the painting I did of a bowling ball. It was a square, monochrome black painting with three finger holes, and I liked it.

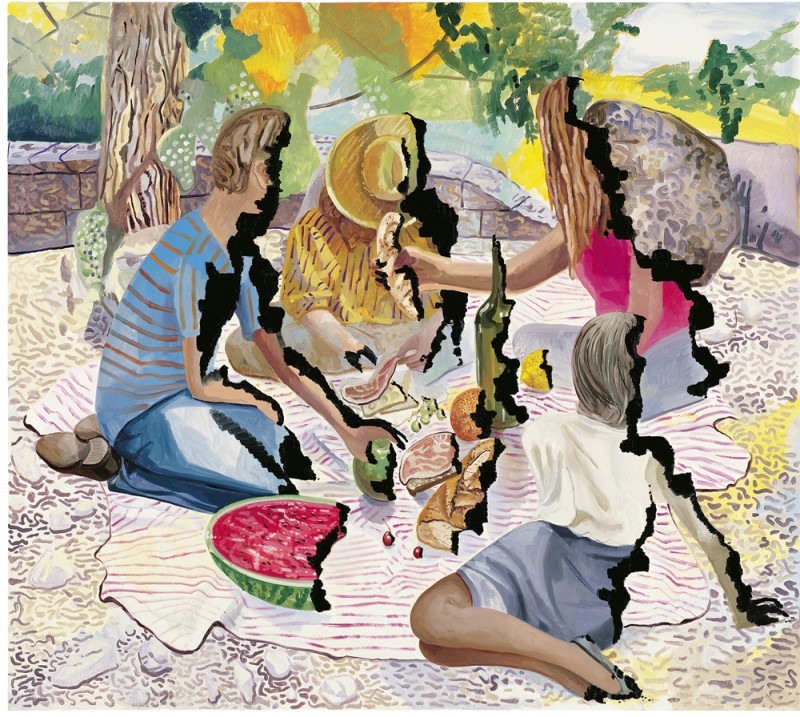

Singed Picnic, 2008, oil on canvas, 80.25 x 90.25 inches.

Historical Reenactment with Plants (I’m into Conceptual Gardening), 2008, oil on canvas, 86 x 120 inches.

There is something rather individual about the way you apply paint. Was that something you were already aware you could do?

There is a moment when your painting asks what it could need next and that was something I was interested in. Before that I was making paintings where everything was taped off and there would be some kind of painterly event going on. I wanted to get away from that after Cleveland because I wasn’t having fun making them. I would spend all this time taping something off and then make a splat and watch it dry. It was very depressing. I wanted to make pictures with space and starting to do that was really uncomfortable.

You were at Columbia when 9/11 happened. Did that event have an effect on you as an artist?

Definitely. It came at a time when I didn’t know what to do, but it put things in perspective and I started to feel like I had to make something. There was a kind of urgency among my friends and you could go either way. So you’d ask, what’s the point of making this, but it was also liberating.

It’s easy to see a character like Frank coming out of a new world order where there is no order. Were you dealing with a post-apocalyptic condition?

It was very uncomfortable because I had started that painting of Frank before September 11th. I was working on it when that happened. So I did wonder if I should stop making the painting. At that time any kind of representation felt up for grabs and I didn’t know how it would land, or if I could even deal with certain subject matter. The feeling I was having at the time was more a question of could I do this? I ended up making those paintings because I liked the premise. If there is no other person around, who’s to say what this person looked like? It felt like I could have this open space for a painting. Even how I chose to paint him felt very open.

You have always had a capacity to make the world up, forgive the reference, from ground zero. You do the same thing with the “God Paintings.” Because it is such a preposterous subject to paint, everything is possible. Have you gravitated towards subjects that give you a freedom to do anything you want?

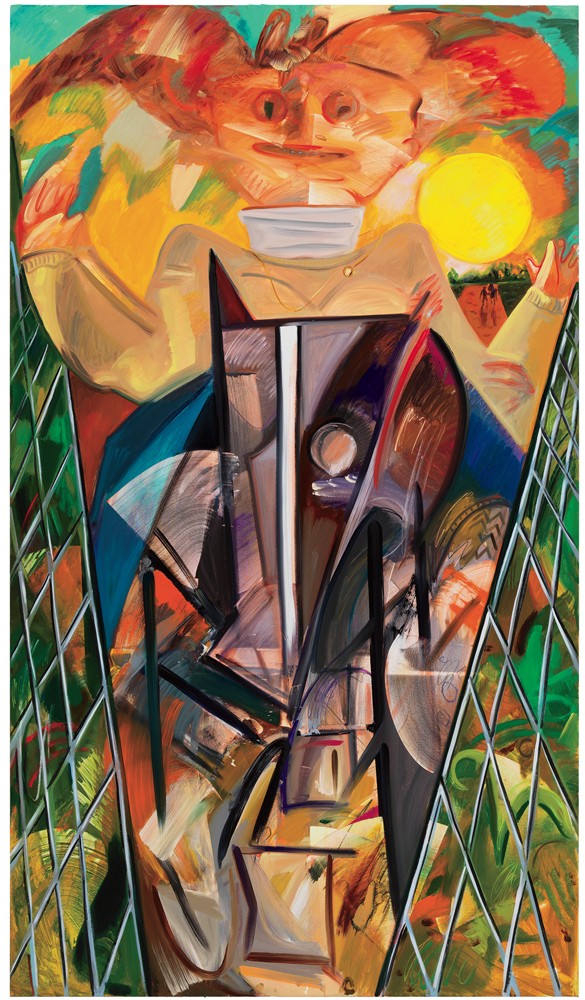

I think so. That was the appeal with the “God Paintings.” The challenge was beginning with how to paint God. I feel painting can really deal with these subjects. As it turned out, the “God Paintings” ended up being more abstract and more about the process of their making.

Poke, 2010, oil on canvas, 40 x 36 inches.

In certain traditions, like Judaism and Islam, the idea of making an image of God is fraught.

It is a subject that can only exist in fiction. Whenever it exists in a form, it is usually a fictional form and it can be loaded. What’s different in America is that God is much more a pop-cultural reference. People have a personal relationship to the image of God; they tend to really personalize it. It interested me that the paintings could be so subjective.

How many versions of God have you done?

I did six. The seventh one was in a drawing. It was intense making them because they are so vertical. Any time you make a painting so much taller than you are, it is hard to structure. There was a lot of going up and down the ladder. After making them, I wanted to have more pictorial space again. I wanted to make a picture where there was a lot of big empty space.

They run a pretty wild range. God 2 has a sawtooth appendage and includes the kind of peppermints that come with the bill in bad restaurants. You’ve even got that guy with the hairy chest and his stuff hanging out all over in God 6. There are hands reaching in to touch him from both sides of the painting. What determined the directions you could go with your gods?

It felt like they were almost proposals. I was thinking God 2 was like a self-illuminating fish at night, or a kind of subject that was angular and metallic. In our neighbourhood, there are very angular-looking people who walk around with carts collecting metal. There is this great David Lynch description where he talks about these giant birds that run through the night. I was thinking about the subject in that way, and also about subjects who could think they were God. A lot of these people might be a little crazy.

With the security guard and the peppermints I was thinking about the façade of a building where you come in or go out. The mints are the sort of thing you get when you’re coming or going. They were really free associations and they were hard for me because I’m not all that religious. They just became their own kind of painting. It was challenging to figure out what these things could be.

I’m interested in how your imagination works; you start off with an idea about what God might look like, and then as you’re making the painting does the God begin to tell you what he or she wants to look like, rather than your deciding what it will be?

Totally. You have an idea when you start off but then the painting really goes off on its own. And there is always this balance in the attitude of the thing. It will want to steer in one direction and I might want to steer it back. If a painting is ever going to work, it has to have its own life in that way. It doesn’t always happen, but there is a moment where it starts to become a real thing in the room and that’s an exciting time. I was also drawing a lot and the drawing was changing how I was structuring the subjects. They became compositionally really structured, more so than the other paintings. They were so compressed that the subject and the painting were the same thing.

Shaving, 2010, oil on canvas, 72 x 84 inches.

You have said that your approach to painting is very structural. Are the “God Paintings” as much about structure as they are about subject and content?

Yes. I am always aware of the framing edge. I think of it as a real thing that the subject can push off against, that it has a real tension. These become even more structured within their format. I think about the painting by asking, “How does this thing exist in the space?” There is the deep space of the painting and there is also the actual space of the rectangle that it’s on. I constantly go back and forth between the two.

Earlier you used the word facture, which is a very structural term. But in 2006 you said you wanted to move away from facture towards what you call “atmosphere.” What determined that shift?

It was because of the subject. I had been painting subjects that were about building and that worked really well, but then the subjects became more attached to language. So I had to reconsider how I was painting. It felt like a really painful time because I knew what I didn’t want to do but it was hard to figure out what I really did want to do. I still wanted to have this kind of volume but I also wanted them to feel lighter; I wanted them to be more fluid and the paint to be thinner. Maybe it wasn’t atmospheric but at the time it was the only thing I could think of, or that’s what I wanted them to look like. But they went in a direction that had lightness and speed. I remember it was tough because I was changing how I was approaching the subject matter and trying to figure out how to paint these things. You are always trying to figure out new ways of working. After 2006 I started cutting holes in paintings for a while, and then making these stains. But ultimately what really helped was I started drawing a lot more. That changed the touch and even the approach to these subjects. I realized I actually was interested in colour and I did want there to be facture. Sometimes you don’t really know what is important in your painting until you see what it’s like without it. I do like the paintings with the holes in them. I couldn’t have made too many of them because at a certain point they were either too little or too much. They could have used some other sculptural element, or they shouldn’t have had a hole in them in the first place. I thought they ended up working like pictorial paintings. Spatially, I liked how the black worked.

You cut through the canvas like Lucio Fontana and then put black velvet behind the hole?

Yes. It sounds totally corny and like the worst thing you coulddo. Velvet and magic seem bad with painting.

It’s like a cheesy magic trick.

Yes and paintings shouldn’t be a magic trick. But I liked how they functioned. There is something about actually physically cutting into the pictorial subject matter. I think the few that I made worked.

It is interesting that you can make a painting like Female Nude in this way, and you can also make an abstraction.

In a way I was thinking about them as abstract paintings. They started with an idea I never ended up pursuing because it seemed like bad algebra or something. I was thinking, “What if the world had ended many times over and you had to reconstruct all the art that you found? How would people reconstruct things based on what information was left?” So it’s like the Met collapsed and what if you saw it all as being by one really prolific folk community? I was also thinking that in Cleveland there are a lot of cubist paintings; there was always an assignment where everyone had to make a cubist painting. So they are everywhere; they’re in the coffee houses; they are in people’s apartments; there are cubist paintings with sand in them. In Cleveland there are also a lot of figure paintings, and amateur figure painting doesn’t often fit in the whole figure. So it is people without eyes. I was thinking, “what would a culture be that really values cubist paintings but can’t represent eyes, and could you find meaning in this?” Then it started to feel that I was going off too far, but I did think about these subjects as coming from an abstract place.

You’re more a product of Cleveland than Detroit.

I probably am. I really like Cleveland and I had a great time there. When I was there I thought I was in the great big city. But I wasn’t allowed to drive that much when I was in high school, so if we did go to Detroit it would usually be with friends, to a club or a rave. In Cleveland it was great being a person in your 20s. They had a really good music scene and the museum is great there. They have an amazing Morris Louis painting.

When you talk about painting there is always a kind of logic to it. If there is self-eating going on, then it stands to reason that reconstruction would also be happening. That’s a reasonable thing to have happen.

Yes because it’s all a process. Then you think, “what would happen next?” There was a lot of that kind of logic with those earlier paintings, or even in the paintings where I joined verbs together. I think certain verbs made sense together more so than others, so it was coming from a logic.

You say you like to think in threes; so you get swimming, smoking, crying. The way I see it, smoking and crying make sense but I’m not so sure about swimming as part of that trilogy. And in your kitchen painting you linked having a pet with bladder problems and cooking. The connections you were making in those triangulated paintings aren’t always that easy for the viewer to follow.

I think the combination in the cooking painting was as simple as thinking about something indoors. When you’re making a painting it starts to follow a logic and to have its own rules with which you go along. So that was why I didn’t think of the early paintings as surrealistic, because I felt like they were proposing a real, actual thing and then following out that logic, as opposed to taking things out of context.

If you’re a surrealist, you’re a pragmatic one. The tinge of Surrealism that is occasionally evident in your work always has a practical application. It’s not about the other-worldly; it is about the being-in-the-worldliness of things.

That is what interests me. You know, I like the world; I like that things have weight and that they can fit on things; that objects affect other objects in a kind of physical and sometimes practical way.

I know you were a high school swimmer but obviously you never smoked and swam at the same time. Did you swim and cry at the same time?

I don’t think I cried but I did scream in the pool, like a teenager would. When I was on the swim team I was in the ninth grade and it was an emotional time. A lot of people would do that on the swim team because you could scream underwater and nobody, supposedly, could hear you. That painting felt like headspace; it was so much about this interior space and signs of distress.

Building the Boat While Sailing, 2012, oil on canvas, 120 x 156 inches.

If the world is fragmented and broken then obviously you would want to piece it together again. One of the ways you do that is through some kind of surgery. Was that the logic behind paintings like Presentation and Surgery?

Yes. It also felt like a natural parallel to painting. The subject itself could be moved around or manipulated on the tables. I love those old medieval surgery paintings, or maybe they were closer to torture, where something is clearly happening to something on the table. The way it is painted is very descriptive and straightforward and usually pretty intense.

There are, of course, precedents for those paintings, Thomas Eakins being the obvious one, and the onlookers in Presentation could be a crowd from James Ensor. You have said that you don’t make paintings out of other paintings but it is clear that you have looked at a lot of other painting.

Eakins was in the back of my mind with Presentation. I normally don’t like him but I remember being blown away by The Gross Clinic at an exhibition at the Met in 2002. I’d like to see it again because I haven’t seen it for 10 years but I was struck by how much information there is in that painting, with all the people in the audience and everything that was going on.

That seems to be how you work; you don’t gravitate towards a painter as much as towards a single painting, and that becomes catalytic.

I think that is always the case. You can get carried away with a painting and the thing you need and what you relate to is all very specific. There are artists whom I love but it is really about the specific painting.

The Autopsy of Michael Jackson pushes the forensic gaze about as far as you can. I was surprised to realize that you painted it in 2005 before Marlene Dumas does her Dead Marilyn. He was still alive when you painted it, wasn’t he?

Yes and I didn’t realize I would feel so horrible when I was painting it. He spent so much of his life in public and he had so much to do with the ’80s, which is when I grew up. In 2005 I saw how he had changed, as had the country. I thought it was an interesting subject but it was a question of how to depict him. I decided it was better if he started to become more like he was at that time. He had such a hand in the making of his own physical image and his own body that you’d never know how he would look when he died. So he felt like a hypothetical subject. It was tough because I didn’t want to be mean. I was trying to be tender but I also had to keep the subject displayed like it was. I wanted the bed to look a certain way, so the floor was flashing like the lights in the music video of “Billie Jean.” I have painted a few musicians but they have always been very vertical paintings and have been empowered subjects. There is something more vulnerable about Michael. I wanted the painting itself to feel like a body; I wanted it to feel intimate, as if you were a witness coming upon a body.

It’s interesting to hear you say that you didn’t want to be mean. No matter how difficult the paintings become, you’re never cruel. Do you go out of your way to be nice?

I never think about it either way. You see the subject in such a way that you mirror the space in front of the painting. Potentially, you feel this is a real person or a real thing, so I never think I’m being nice or mean, only that I’m engaging with this thing. But dealing with the death of a man was such a loaded subject.

In Men’s Retreat Bill Gates and Ted Turner turn up.

That time I was using a lot of real people. There was a woman in the US named Terri Schiavo, who had been brain dead for a long time and she became a political lightning rod about the right to die. I painted her, or something like her. It’s tricky with live subjects because you want the painting to have it’s own life and you have feelings about the subject, but you also want it to be open and that has a lot to do with how the subject is represented. I always work around the edge. I think there is empathy in Men’s Retreat as well. I was thinking about it as a situation in which the blind are leading the blind.

Was Poisoned Man about Viktor Yushchenko, the president of Ukraine, who had been poisoned by dioxin in 2004?

Yes. I thought that was such an intense story. There is something about the face of a man who is also a politician. He has a very public façade. I was thinking of Dorian Gray. It was really weird because he ended up looking like his opponent.

The person you have been less kind to in portraits is yourself, like when you do Self-Portrait as a Pachyderm. Why are you so unforgiving with yourself?

I didn’t think about it one way or another. Maybe it has something to do with how you feel yourself in a body. I think I have bad posture.

In 2008 you did that amazing show in Berlin called “If It Appears in the Desert.” Does that exhibition indicate a shift in your painting? There were works in it where the black space was the body’s absence as much as its presence. What was going on in those “singed” works?

I was thinking about it as an event, something that happened outside the painting that could affect some parts of the painting but not others. I wanted them to feel lighter. At the time I couldn’t quite get that. Now I feel more confident. I had been looking at a lot of late Picasso paintings and I loved how open and airy they felt, and the drawing was such a big part of them. I wanted that lightness at the same time that I wanted to render the interest I had in the subject matter. So the Singed Picnic was like a picnic in Central Park with good French food. I was interested in a halted pictorialism, something that could read as a picture but then there could be something that happened outside the picture. Up to that point everything was contained within the rectangle.

Flossing, 2014, charcoal on paper, 36 x 24 inches.

I thought less about Picasso than Picabia in looking at this painting.

I was looking at a lot of Picabia and de Chirico.

I know that you are sometimes frustrated by critical responses that pick up on the Surrealism in your work. Here’s an opportunity for you to state your relationship to Surrealism.

I think those paintings definitely have something that is like Surrealism. The main thing is that I really believe in the subject and it’s hard for me to think of it as something that is dreamlike, or out of time or out of space. I like the way Kafka deals with subject matter. They can have a dark, nightmarish quality to them but ultimately they are so much about the practical-ness of the subject. So this guy wakes up as a bug, then what happens?

Once you accept the fact that you’re an insect you still have to deal with your family and your job. You have to find a way to go on. That’s where your practicality comes in.

Or even ideas about problem-solving. That is the interesting thing with fiction; someone has a problem and that makes the thing worth reading. Maybe my issue with Surrealism is that it seems like there is no consequence to objects or things. I have less of a problem with the association now. With those paintings I was looking at a lot of Magritte. I think the issue I had before is that it would take the subjects outside of the world into a fantasy land and that wasn’t how I was thinking about them. I was thinking about them as real things.

Your distinction is a nice one. You don’t go above the real. For you, these are real situations and real characters. They are definitely not fantastic.

That’s the thing that appeals to me. I love monsters and zombies and superheroes but once they’re not on earth, I just can’t follow. The second you take it up into a spaceship, or if it happens in a faraway land, I can’t go there and I lose all interest. I can’t follow hobbits and stuff.

You said earlier on that you wanted to create contemporary monsters. Do you feel you’ve done that?

I was interested in the grotesque. But there is a way that monsters come from culture. While I think some of the subjects can look monstrous, I don’t think of them that way.

The Singed Still Life looks like it might be a study for the Singed Picnic because it uses the same still-life objects—the lemon and the wine bottle—as well as the figure in the blue shirt, but then it transfers his long hair in the still life onto another figure in the picnic painting. That added figure also has a half rock on her back, like a turtle shell. What was the relationship between those two paintings?

They came at the same time and I was thinking these objects could be interchangeable. You could take one object from one painting and put it in the next. They were from this giant storage closet of fringe objects that could be rearranged in each picture. In those paintings I was interested in how different textures and patterns could line up together, or work next to each other.

In Gouged Girl the paraphernalia of the picnic is still there but instead of black abstract edges, pieces of her flesh are being taken off. Because her fingers are red, it appears as if this dismembering is self-administered. Were you thinking differently about this painting than in the singed works where the black absence was prominent?

The thing was that she was potentially made out of watermelon. There is a really great Dalí painting called Girl at a Window from 1925. I think it works in much the same way as the picnic painting but my subject is like a still life and also like a portrait. Dalí’s seems more melancholic.

Among the “I’m Into…” works, I was especially fascinated by QVC (I’m into Minimalist Tattoos). When you render the bracelet, it speaks about Old Master highlighting. That seemed a very conscious and deliberate move. There are two very different ways of rendering an object in that painting.

What appealed to me about the painting is that it is potentially a backdrop for these objects that are rendered in a very different way. I also wanted to have a shiny ball somewhere in the painting. I was interested in these very flat layers that were physical and that come outside of the painting, and then something that was very illusionistic and on display. There were all these different systems of display going forward.

God 6, 2013, oil on canvas, 106 x 72 inches.

When I look at a painting like How We Cured the Plague I think less of a hospital ward than an artist’s studio on the scale of an airplane hangar. It’s like a studio Anselm Kiefer would have, or because of the shark in the foreground, Damien Hirst. Were you thinking of that painting as a way of transforming a medical space into a studio space?

I thought of it as Grand Central Station. Maybe the light does make you think of an artist’s studio, but I definitely wanted it to be very much an interior space. Although not that big, I was spending a lot of time in my studio.

In Female Model the same windows appear, and in the background there is a painter at an easel.

That is true. In Cleveland there were these spaces with giant windows on which they would have to put those black cut-outs of hawks so that birds wouldn’t smash against them. When I imagine a space, it tends to be one in which I have had some experience.

It interests me how often your work depicts the painter as the person who has to figure out how to imagine and then render a world. It’s in Chicken and Egg and it certainly comes up in Assembling an Octopus. For you, it seems the painter is the quintessential maker.

Yes. On one hand, the artist can play that role. But there is something amateur about them, as if they were art students. For example, in the life drawing class in the Octopus painting. Life drawing is such a unique experience, where everyone is together but they are also isolated in their own drawing. I was thinking about that as a filter on top of the subject, so you could see it through these art class renderings of the subject. There is also a painting called Painter in which there is an old French countryside painter person. I also see the humour in the role a painter could play.

But in both Assembling an Octopus and Building the Boat While Sailing, you’ve made big ambitious paintings about this idea of the world being constructed as you go along. What I’m getting at is that your world is always being built out of the painterly imagination.

I think that is true. The subjects tend to be built and there tends to be some problem within the subject. Building the Boat While Sailing was meant to be all about the process of making it up as you go along. You can’t tell if they’re working or relaxing. I didn’t want them to be using tools, so they’re using their bodies to build the boat. And there is something about using their bodies that was in between their being performance artists, who almost performed the boat, and just doing an actual task. I wanted it to be in between those two ideas. A lot of building corresponds to making the painting, so it mirrors the feeling of making. Making a large painting could feel like you’re building a boat.

Of course, when you’re on the ladder making these large paintings, you’re the one who, quite literally, is performing the painting.

I have this stepladder and it does feel very aerobic. Especially with the “God Paintings,” I was going up and down and up and down. It was tiring.

In the boat building painting you clearly have Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa in mind and I see the presence of Max Beckmann and his beach paintings in Assembling an Octopus.

I’ve been thinking about Beckmann a lot, how he structures his subjects and how awkward they are. The format of his painting is sometimes very narrow but he can get so much information in there; the subject will compress or go aerial. I had ideas about all the action I wanted to happen in the painting and was faced with the challenge of figuring out how to fit all that subject matter into a dominant picture structure with the addition of these little areas.

The upside down woman with the perfect pubic trim who is gazed upon by a boy is very close to a Beckmann beach figure.

Yes, he would often have people upside down. That was a weird decision. I didn’t know if she should be truncated like that. At one point I thought she should go horizontal in the middle of the painting. It’s odd to put this torso right in the middle of the painting but I felt in a way it related to the painting itself. The boy was looking at her and I wanted the whole painting to seem like a giant eye.

The boy represents a young version of the male gaze, while the top-hatted man near the top of the painting could have come out of a Manet painting. I look at Assembling an Octopus as being about the trajectory of our looking through painting.

I wanted it to be about looking at things. Also, the octopus seemed like a giant eye. But it’s also like an invisible subject that you can’t really see. It is always compressing and changing its form. I wanted everything around the octopus to be both trying to observe it and blocking it at the same time. In the same way you can’t see the whole of an event; you always see it through individual glimpses. And then there are times when you get an accurate picture of how things look because you have all these different viewpoints.

The drawing for Assembling an Octopus, other than the absence of colour, is very close to the finished painting.

Sometimes I make the drawing after the painting to see how it can work in black and white, as well as to see it with a different kind of atmosphere or space. I used the drawing for the painting, and then I finished the drawing afterward. It goes back and forth.

So drawing is an important activity for you in the studio. You use it in generative ways?

Usually there will be a very rough sketch of an idea. But I have also been making drawings where I work out the complete structure of the painting. Those tend to be drawings on their own, and then I have been starting paintings by drawing in thinned down oil paint and trying to work it out more fully as a drawing first. The way I had been working before was to paint the space first and then populate it. I’ve wanted to wipe things away, or have things seem like they just happened, so that the painting has this sense of speed to it. I’m attracted to what the subject can look like underneath the painting because as you’re erasing it, you’re running back into the initial drawing, and then you go back and forth from that. The drawing for Girl On A Horse came after the painting.

When I look at that drawing it makes the de Kooning rider more obvious and the cubist composition is also structurally more clear; all the cones and the shapes are more obvious there than they are in the painting.

The drawing was so much more structured. With the painting there was so much scraping off and building up that it became another thing. The initial idea for the structure was closer to the drawing but it changed while I was painting. Maybe the structure of the horse felt more compositional.

God 5, 2013, oil on canvas, 106 x 72 inches.

You have a remarkable way of transforming the quotidian. You do it in Shaving, or in Flossing, where the guy has a formidable erection. You take commonplace human activities and turn them into something completely fascinating.

In the case of Flossing there was something about the feeling of flossing, the erection and the shape of the triangle going up to the mouth that seemed to work. Maybe it is not so much conscious as built into how I approach the subject. I humour any idea and see if it can go somewhere. Shaving was a worst-case scenario. It is a real fear when you’re shaving. It may be different for women, but I find the thought of it really painful and I wondered how could that work as a painting. Flossing is a much simpler idea. I thought I could make a nice drawing and with the teeth and the erection, it also reminded me of death.

The paintings get frisky, too. Making a Movie in Bed and Bed Parts have some erotic things going on—there is penetration and some rounded buttocks.

I like the space of the bed as something that could relate to painting. It’s also a very personal space and a very specific setting for a subject. If there is sex in the paintings, it is usually pretty awkward for me. There are moments where eroticism happens but it is very rare. In earlier paintings of Frank there were erotic things, but to my mind I don’t think I have made a generally erotic painting.

In Devoured by the Bed, I was reminded of a line from the Canadian poet Robert Kroetsch that goes, “the bed is ark to all the world’s destruction.” For you the bed is ark to either the world’s deconstruction or its re-assembly. The bed space is a structural problem to solve rather than an erotic subject matter with which to engage.

Now that I think about it, Devoured by the Bed does have an erotic feeling. There is something about falling into the plane of the picture, of the subject getting sucked in. I was thinking about the bed as potentially a dirty sheet or something scatological but I haven’t quite made that painting yet. For me, an erotic subject can come out in different ways and not only as a straight-out depiction.

Your work makes lovely confusions because of this complication of the quotidian. I mean, the simple idea of incorrectly buttoning up your sweater, or getting dressed all at once, presents a wonderful kind of confusion. Are those kinds of things simply observational?

Buttoning your shirt wrong is something that always happens. In a lot of the recent paintings people are wrestling with their garments. I was thinking about it as something that comes between the viewer and the subject and that can press itself up against the painting. A lot of them were things I have had trouble with. There is a dressing room painting where there is the feeling that the pants are too tight to get on. Everything just feels very physical, like trying to undo your bra from underneath your shirt. They’re ways of feeling your body within a container.

What Cubism did was to provide a way to recognize simultaneously the existence of a whole series of spatial areas. In paintings like Getting Dressed All at Once, you do the same thing with subject matter. You take time and render it as simultaneous.

I wasn’t thinking of that but now that I look, it is definitely there. I was thinking about the compression of time, the time in making something, and also that something could slow down. I still want it to read as a singular dominant image. The thing with something like the horse and with Getting Dressed All at Once is this frontal address where the subject directly looks at the viewer and just snaps into one moment. That was important to me. I thought about calling it “Women Maintaining Eye Contact” because that was the bigger reason to make the painting. It was ultimately so much about the eye. While all this other activity was happening, the bigger subject was the eye contact. I was looking at a lot of late Picasso and really loving those paintings. I wanted that painting to look more like the face was a plane you could draw on.

The subject of the eye and perception comes up often in your work. It becomes a meta-subject for you. Is it about a close-looking phenomenology?

Yes. It has always been there. If you can see something, then it exists as fact. I am always interested in the idea of observation. Even if it is something totally fictive, it is still a way to say that this exists. How do you know what something is when you can’t see it? So you end up feeling it and a kind of abstraction can go on when you’re piecing together an image you can’t see.

You said that it is important to be a little bit uncomfortable with what you’re making. Do you still feel that sense of discomfort is necessary?

I think the exciting moment comes when you think, “Can I make this?” You don’t know if you should make a painting of something because it is too personal or too awkward or a really weird subject for a painting. Then you think, “Well, how could I do it?” and then it becomes really interesting to begin to make. It is always uncomfortable. And sometimes when you see it in the real world you think, “Oh my god, I spent all this time making that and it’s too late to go back.” With new work you don’t know if the way you are painting makes sense.

God 2, 2013, oil on canvas, 106.125 x 72.125 inches.

In a recent interview you said we are in a time in which we are constantly producing and reshaping our own images through the images we pass on. Does it beg the question about what you are passing on through the production and reshaping of your images?

That’s a good question. I don’t know. I want the paintings to feel singular and alive. It’s so different for each painting but you can never quite know because you’re involved with the making of it at the time. I would like the paintings to feel like they have their own personality.

The one thing you don’t have to worry about is that your paintings lack personality.

It always depends on what you’re making at the time. Being surprised by a painting is the main goal. If you are surprised in the making, then it might surprise someone else when they’re looking at it.

Good painters are ambitious for their work. Do you locate yourself in that ambitious frame?

There is always great art being made and so the conversation is constantly shifting and changing. The only thing you can do is to make work that you find interesting and important. And you have secret competitions in your head that are too embarrassing to admit.

Is the measure against other painters or is it self-generated?

It is self-generated and it is also possible to be competitive with painters from all over time. But for the most part, it is self-driven. You feel like you’re competing with your own drive to make something better than you have so far.

I can’t tell the gender of your figures. Are you deliberately obscuring gender?

It may not always be that conscious. I often think, “Who is this person?” A lot of this may be coming from my own sense of self, in that I don’t feel that I’m particularly male or female. I’m just making the painting. ❚