Frank Speaking: An Interview with Robert Frank

Introduction by Robert Enright

Interview by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh

Robert Frank’s newest video, The Present, opens with a shot of a window in his Mabou, Nova Scotia house beyond which you catch intimations of the Cape Breton landscape. As you watch the essentially static frame, you hear Frank’s voice saying, “I’m glad I found my camera. Now I can film,” but immediately the doubt begins. “I don’t know what story I would tell. But looking around this room … ” and the camera pans across a densely cluttered workspace, ” .. .I really should be able to find a story.” And so the film progresses, finding a number of possible directions in the quotidien details of his life and environment. It could be a friend; it could be “just mirrors,” he says impishly; it could be a story of flies dropping from a windowpane “in fatigue or ecstasy. Who knows?”

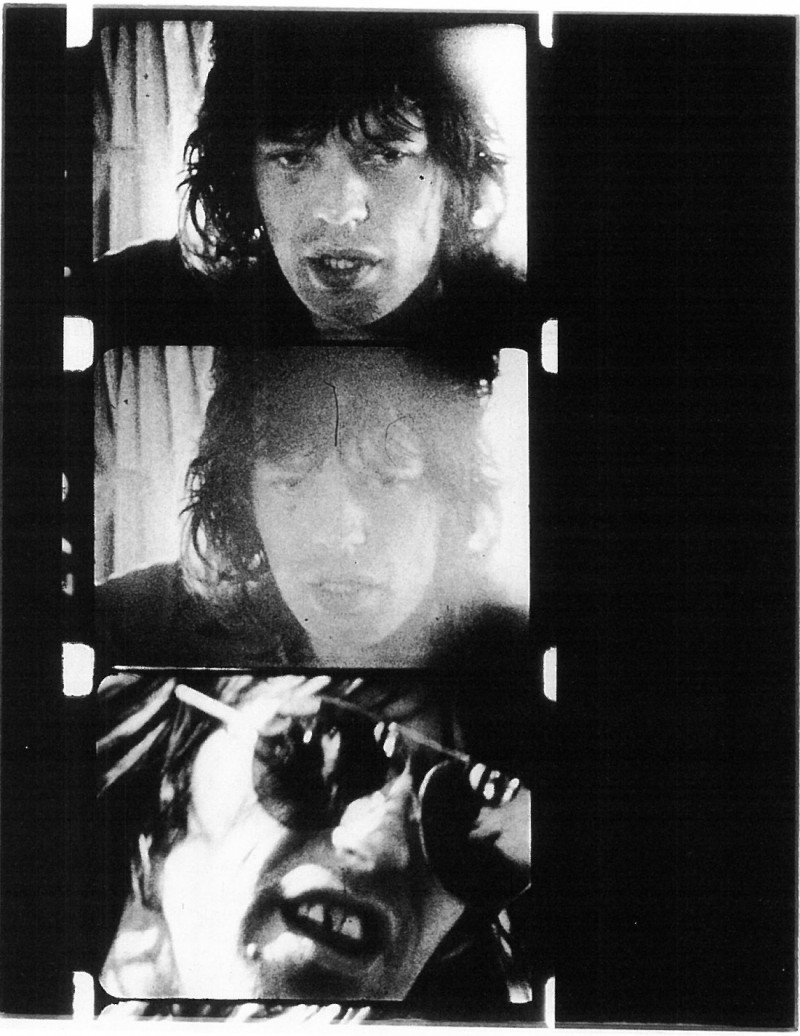

Mick Jagger, enlargement from Cocksucker Blues, 1972.

What we do know is that Robert Frank’s moving and compulsive inhabitation of memory is an occupation that cuts in two directions; it assuredly gives him a story but the results often can be painful. The camera looks out the window again and this time we see evidence of his memory recorded in his unmistakable handwriting: “the suffering, the silence.”

If Franz Kafka was right in observing that we photograph things “in order to drive them out of our minds,” then Robert Frank has been an astonishingly unsuccessful photographer. In a career now spanning almost five decades, he has been among the modern period’s most singularly personal image-makers, taking pictures and making films that mirrored an emotional life of occasionally unbearable intensity. In 1977 he said that “only the people who are obsessed should continue with photography,” and Frank has taken his own best advice. The Americans, the landmark book he published first in 1958 in France and then a year later in America (with an introduction by Jack Kerouac) was initially viewed as a document tracing a radical shift in American life. Taken during this Swiss-born photographer’s journeys across the U.S. on a Guggenheim Grant, The Americans is now properly regarded as a book more made than found, as a vision of America equally about self and society. Since then the direction of Frank’s art has been progressively more autobiographical; certain of his films have been relentless interrogations of himself and his children, Andrea (who died in a plane crash in 1974) and Pablo (who was troubled by severe psychiatric problems). These films are both courageous and aggressive evidence of a caring parent attempting to understand what had gone wrong and what can be made right, and the operations of an emotional stalker intent upon using his children as film fodder. I may sound like Frank himself when I say that these activities are simultaneously true and not true. Inside the world of his photographs and films nothing is fixed and anytime you feel secure, it is just a prelude to a shift, often of revolutionary proportions. In the following interview he praises a small film called Keep Busy by saying that “it’s more how I look at life. It has a certain disaster and disorder and chaotic-ness and insanity. Everything is upside down.” And earlier on he compares himself to the crows outside his window who pick food out of the garbage. “They get the good pieces,” he says, “You don’t have to go the easy way and there are no shortcuts.”

There is nothing easy about the way Robert Frank has gone. But what he has produced along the way is the most important, uncompromising and compelling body of work of any photographer/ filmmaker in this century. I want to return to The Present because it is his most recent film and his best. I’m aware, in the face of achievements like Pull My Daisy (1959) Frank’s magical Beat film, Cocksucker Blues, his revelatory look at The Rolling Stones on tour in 1972, and his unparalleled “home movies,” that this claim can’t go unexplained. But its greatness lies in the way that it holds, in perfect suspension, the weight of Frank’s obsessions and his manner of dealing with them. In his late poetry W.B. Yeats was able to pare down his complex vision to a few images, so that in poems like “The Circus Animal’s Desertion” he played minimalist summarian to his own densely imaged past. Something of the same reduction occurs in The Present. The video is like a brilliant haiku in the great long poem that is Frank’s life; improbably it is all his films rolled into one, a species of meta-metafilm. In saying this I don’t mean to imply it is a closed universe of loss and remembrance. To be sure, it operates in the opposite way; The Present virtually explodes out of its narrative frame. It is sombre, playful, angry, theatrical and so thoroughly aware of its own subversion that it’s almost comforting. Frank refuses to settle into certainty—his is a profound epistemology of doubt—and his denial of the place of knowledge in the world can be delightful. He points his camera at a horse and asks, “What kind of animal is this? This is an animal that is called…” and his response trails off into the ellipses of silence. While we see a boat and a shed we hear, “This belongs to…” and then nothing more. Frank asks about a dog which has spent all of its life looking out windows; he says people are a good subject and he films crows instead. “It’s gonna be a crow’s movie,” he himself almost crows, and asks a bone mask attached to a stick for a response. “No answer,” he says, mocking his own compulsive search for something to hold onto. And throughout the film is his recognition of loss and of memory, its annunciating messenger. At one point he determines to erase memory—the word has been written in thick black ink on a transparent pane, which his friend finds impossible to remove until Frank says, “there must be some truth to memory if it won’t disappear.” Immediately it comes off. But Frank won’t let it be. Two-thirds of the word is removed and we’re left contemplating the word “me” and we’re made startlingly aware that Frank’s word surgery had been a way of finding intact his own identity and his certain uncertainty.

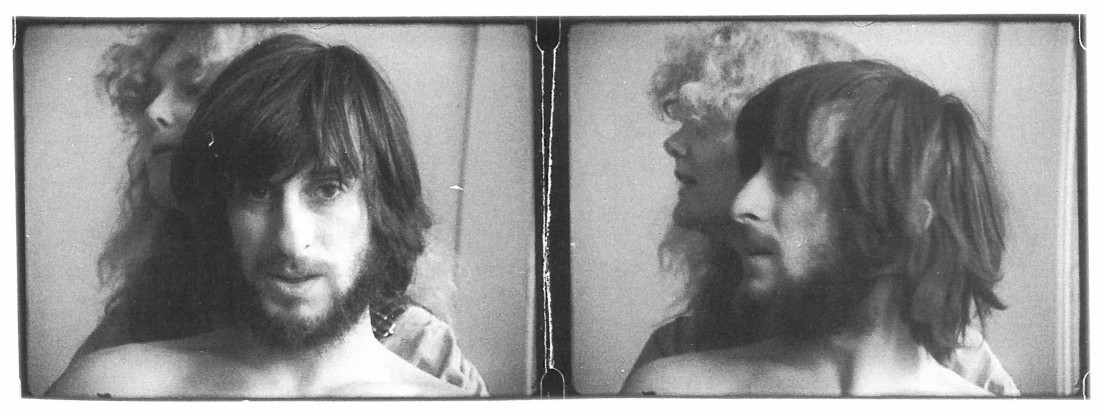

Frame enlargements from Me and My Brother, 1965-1968.

The most painful aspect of The Present is how much what has happened in the past sets the emotional tone for the present. Frank may be “sick of goodbyes” but he can’t help uttering them. He has ritualized loss and it plays a crucial role in his life and art. Ritual is a way we give form to emotion and in that sense it is a control. Or it may be more accurate to say that ritual prevents emotion from running roughshod over our beings. So in the process of memorializing loss, Frank has ritualized it. Its expression— in image and in text—is mantric. There is a telling moment in the interview in which Frank speaks to his romance with change. He regards approvingly the notion that “everything I made will fade” and then goes on to repeat “an absolutely wonderful quote about life” from Flannery O’Connor: “Where you came from is gone, where you thought you were going to never was there and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.” Frank’s delight in the face of an obliterated certainty puts me in mind of Robert Walser, the Swiss writer who is as good as Kafka and no less black. Both Frank and Walser negotiate this slippery emotional territory. In “A Little Ramble,” a peregrinating story written in 1914, Walser says that “we don’t need to see anything out of the ordinary. We already see too much,” and in so doing anticipates the privileging of the quotidien that is at the centre of Frank’s art. Or in his epigraph for Eine Art ErZiihlung (1928-1929) Walser says, “the novel I am constantly writing is always the same one and it might be described as a variously sliced-up or torn apart book of myself.” If you change the art form and add “put together” to the fragmenting process recorded in Walser’s aesthetic, then you have Robert Frank composing in images an identical book of himself. “The films I have made are the map of my journey thru all this … living.” Frank wrote in 1980:

It starts out as ‘scrapbook footage’. There is no script, there is plenty of intuition. It gets confusing to piece together these moments of rehearsed banalities, embarrassed documentation, fear of telling the truth and somewhere the fearful truth seems to endure. I want you to see the shadow of life and death flickering on that screen . June asks me: “Why do you take these pictures?” Because I am alive …

The following interview with Robert Frank took place in Mabou, Nova Scotia on August 25, 1997 by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I want to start by talking about how Mabou feeds you when you’re here?

ROBERT FRANK: It’s nature, it’s the scale of what you’re in; everything’s so big. Just to be here and listen to the leaves, the wind, to listen to the waves, the things that I don’t have in New York.

Is it a question of being in awe of nature? Relative to its power, do you feel small?

In the beginning I felt very small, especially in the winter. At that time the driveway was almost impossible to drive up and you would see this small figure walking. There was something very strong about that. I think the winter taught me much more because I had to cope with nature. It can be very cruel. You know it’s bigger than you, so you are happy to be able to burn wood, to keep warm and when the storm is over and the sun comes up, then you feel good. There’s no feeling good like that in New York; it just doesn’t exist.

When you looked onto the winter landscape was it a white slate that you could allow your thoughts to move onto, or did it actually give you something back for your work?

Mabou, 1994. Courtesy of Pace Wildenstein MacGill, New York.

Well, I certainly did take photographs, more so in the spring when it began to melt. The only thing that’s here are these black crows. They’ re really company; you begin to watch them and feed them. You get to be their friend and they know you, too. It’s the first time I had a relationship with animals. And I learned from the people here. They’d be aware that there was lots of time. I wouldn’t have to be frantic because my car got stuck. They’d say don’t get excited. If not today, maybe tomorrow. Now it’s changing slowly; there are four wheel drives and speed boats. I feel we had really the best of it here.

Did you see the film Smoke? The reason I ask is because of the project taken on by the guy who runs the smoke shop; every day at the same time he sets up his camera and takes a picture of whatever is going by on the street. It’s an ongoing diary and a lovely conceptual idea. Did you ever think about systematically documenting what this place was like?

No. Concept is something that is used by people who think a lot, who are very logically trained and I’m really afraid of concept. A long time ago—in the ’50s or early ’60s—there was a guy on 23rd Street who I never met, a commercial photographer, I think. He had a little showcase on the walls, and each day he put something in there, something he found on the street, or some words. It changed every day. That was before Conceptualism was blown up big and shown in museums. It was very good, one of these silent cries in New York. I’ll never forget it and I don’t know who he was. But I mistrust Conceptualism. I’m not the type. It doesn’t have anything to do with life. It comes from the brain. For me, it has to start with where I live; not with calculation. Whenever I get pushed in that direction I step back.

You’re a scrupulous organizer of your images, aren’t you? Throughout your career you’ve gone back and realized what it was you were getting from the work and then you began to emphasize those ideas. Is it the emotion you’re working when you do that?

I think what was a big help was to stop photography and go to film. No matter what you did with it, it changed. It’s like walking into another room, I don’t want to live in the same room. So you open the door and you go in and you climb out the window and you see something else. And when I got back to photography again, I would incorporate it into the photographs. So you could play with it, try to be original or do things which people wouldn’t do.

A lot of your image-sequencing and cutting-and-pasting is filmic isn’t it?

I learned a lot from making films-about rhythms, about juxtaposition. That was a very good step not to continue on the path of The Americans.

Pablo and Sandy, Brattleboro, Vermont, 1979, from Ufe Dances On.

In the film Candy Mountain, one of the record producers says something about a guy who abandons the game when he’s reached the top of his form. I can’t help but see you as that character. At the top of your form with The Americans, and then with the bus photos, you quite dramatically change and become a filmmaker. Was that a conscious attempt, as you put it, to go into another room?

It was conscious in that I simply did not want to repeat what I had done. That was the logical thing to do. Also I had done a little film before The Americans which I’m now trying to reconstruct.

The film in which Mary, your wife, is like a sea goddess running on the beach around Provincetown?

That’s right. So now I’m trying to get all that footage together again. I had just this one copy, and I gave it to students when I was teaching. I said, “Look, this is an early film I made, I never knew how to put it together, why don’t you try.” So they cut it up again. As a result, it’s in real sad shape because I never thought it would make a film. Now it’s very interesting because of the people in it. Maybe I’ll get it together but a lot is missing. Today it would be no problem; you’d put it on video and you could work with it. You don’t have to save anything that you do, but it helps, you can use it again. It’s like being an antique dealer.

Is your personality such that you are by nature restless? Because you’ve always found new places to go with your work.

I think movement is important, movement in terms of what you use. Be flexible. It’s easy to travel but now my travel is really between two places. I don’t want to be a tourist. That’s finished for me. It’s sad because it is wonderful to go to a new country.

The Americans was in a great tradition of what Walt Whitman called “the song of the open road.” [Jack] Kerouac went on it; so did Thelma and Louise. Was there something especially compelling about just getting on the road to find out what America was? In The Lines of My Hand you sustain the road idea.

The Americans was really the beginning, the first time I was free to do what I felt I could do, to document what I saw. I really didn’t do any other trips like that after The Americans. Maybe Conceptualism happened because there’s so much photography, so naturally you have to find a way to get out of this morass of pictures, this unbelievable flood of images. So using the Polaroid gave me more the ability to say how I feel. And you can write on it. When I did The Americans nobody would write with photographs. It just wasn’t done, it was a crime. But it changes. I got wiser or older, or the time made it necessary. Still, a good picture works without words.

There’s a wonderful photograph of Charles Mingus coming out of a subway…

That’s not him.

So you wrote “Mingus” on the image later?

I did it the day he died, I wrote it first on the photograph and then I scratched in the negative.

Now it’s a permanent part of the image?

It’s the truth. How you can use words. Maybe all the words are lies in the photographs. What is more true, the image or what you say?

Do you know that wonderful tine from Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cookoo’s Nest where Chief Broom says, “These things are true, whether they happened or not?”

Yeah, there are good lines like that.

Tell me about Kerouac. We were at a film two days ago called West Coast: Beat and Beyond, and the place was packed with young kids who came to know more about Kerouac. He’s as fascinating now as he seemed to be in the’50s.

He was just a born writer. I mean he had this memory that would never fail him. The guy would be drunk, lying on the floor, and then two weeks later he would say, “Read this,” and it was word for word. He wanted to be like Proust. But I liked him because he was very modest. He had big visions of himself as a writer and of his books in libraries. Otherwise, he was just interested in the human condition, not in a snobbish way and not in a way that would further him. He was really interested in all the people around him, especially people on the road. He had a very good sense of humour. When we travelled I would say let’s go in here and Kerouac would say, “People like me couldn’t go in here, it’s too fancy. I’m not dressed right.” He was very, very aware of this and he had this weird relationship with his mother.

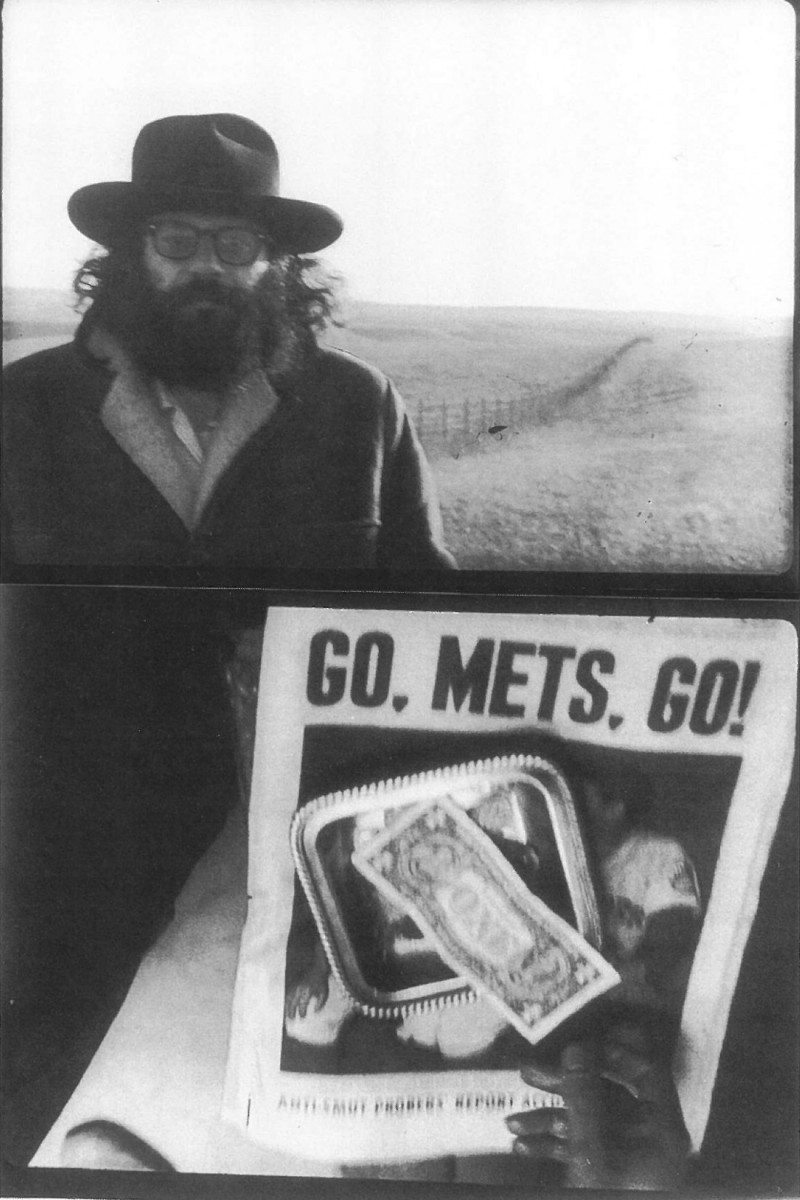

Ginsberg said the great gift of the Beats was their friendship. He says it wasn’t about aesthetics, it was about camaraderie.

They also had the idea that something needed to be changed in the society, and something could be changed. They weren’t so sure what it would be but it certainly would be more freedom to do what they felt like doing. I was much better friends with Allen [Ginsberg] than with Kerouac. I knew him a longer time and the homosexuality wasn’t a wall. But it separated you. I felt Kerouac was really open to anything, to everybody on an equal level.

Was that openness part of the reason why you wanted him to write about The Americans? You sought him out didn’t you?

When I met him I showed him the photographs. But I did read his book. He really loved America. The sentences he writes about this country are absolutely stunning. I can’t rephrase them but they’re haunting—about the night and the vastness of it, about people going to bed. They are really extraordinary.

I love his observation about your work—that you can’t tell the juke-box from the coffin. He seemed to really get at something essential when he talked about The Americans as “a great, sad poem sucked out of America.” Did you like the introduction?

Yeah, I liked it. He was just the opposite of Walker Evans who wrote an introduction which nearly ruined our friendship because I didn’t want to use it. That stilted, well-educated kind of English. Kerouac’s was connected to life. Walker was so conscious of writing; he was a craftsman, making carefully constructed phrases with something very clever in them. Kerouac wrote that thing and said, “I’m not going to correct it.”

But he did a second version for you?

I asked him to write more and finally he did it but he was cursing and saying he never does that. But he wouldn’t correct anything.

One of the things that strikes me about Evans is his use of written language as part of the texture of his photographs. Did that vernacular sense have any influence on you in the early years?

No. I think it would make me mistrust him. He was an editor at Time, Life or Fortune and that was not my favourite place to go. I tried to get work—and he actually got me work—but they were not good experiences. Except working for him was okay. At that time you were more shy and you kept to other photographers who were your friends. You entered these wordless rooms because it wasn’t a group that communicated a lot. They would discuss available light or the camera you used but it was a solitary thing. And you wouldn’t even show your work to many people. You worked pretty much alone.

Did that suit you at the time? The work you did for magazines indicated you had found a way to make the images your own, even though you were essentially working on assignment.

I did try to get into Magnum, but they wouldn’t accept me. I showed them The Americans before it was published—all the pictures. They gave stupid reasons: “All your pictures are horizontal and we work for magazines that are vertical.” Things like that. I don’t know what was needed then. I was lucky still, people gave me work, like the guy at The New York Times. It wasn’t high living but I was willing to take it and be committed to do what I wanted and not to have work with so many different people. And besides I wasn’t good at fashion photography and advertising. I tried but it didn’t work that well.

It wouldn’t have suited your temperament. That pursuit of surface beauty strikes me as not being one of your concerns.

Well, at that time you wanted to make money; you needed to make money. You got some illustrations to do and it didn’t go very far. Whereas you could make a fashion photograph and get a few thousand dollars. That was a lot of money then. The Guggenheim Grant at that time was three thousand. But I’m glad I was insistent on not trying to make money and take a shortcut.

Would you have ended up doing what William Klein did? Klein essentially subverts the whole process of fashion photography in the very act of doing it.

Well, he had a foot in that world first. That was his right foot. And then when he sunk in too much he’d say, “I’ll go where there’s less shit.” I remember it was a very good time when I worked for The Bazaar; they gave you all the material and everything. But all these big fashion photographers in the studio would look at me and say, “Gee, I wish we could be like you and do what we want to do. I wish we could afford to do that.”

The crocodile tears falling down their faces … ?

Yeah. The only friend I had then was Louis Faurer. We developed a friendship because he was the same. But he moved away from that kind of reality and went into the fashion world and was quite successful.

I want to ask you about some of your earlier work. You did a series of photographs of young toreadors that was published many years later as a photo essay in a Spanish magazine. They strike me as being very beautiful photographs. I’m thinking of one in which a toreador does a handstand, his legs arc back and spread below him is the cape itself. It’s so perfectly balanced and so lyric. You must have known you were getting a beautiful image in doing it.

That was one of the rare times I tried to do a story with a beginning and an end. I was never very good at it, so maybe the aesthetics saved the story, if there was a story. I remember the picture very well. There were a few more. At that time I was very aware of trying to produce a photograph that would be faultless in terms of my aesthetics. And be right. That’s when I did Black, White and Things. After that it changed; the trip to America. Not looking at it but feeling something from it.

And shooting in a different style, too. Those European photographs seem more composed.

Frame enlargements from Me and My Brother, 1965-1968.

Yeah, that’s when I shifted over from using the square format to a Leica. And that was really Brodovitch in a way. When he gave me a job at The Bazaar, it was photographs I had taken with the Rolliflex that he looked at. He said I can use you in the back of the book in a section called ‘Shopping Bazaar’. In Switzerland they teach you well. I knew how to mix the developer and the chemicals and how to re-touch a photograph. The guys that worked there didn’t know. But it made me unlearn it all very quickly.

But it was useful knowing it so you could unteach yourself?

It was very useful to know because then you could really enjoy something that was on the other side. But I did one other story about the Welsh coalminer.

How did you meet him? Was he picked for you as a character?

No, I went to look for one.

Was the series a tribute to Bill Brandt who had also done some pretty phenomenal coalminer photographs? They were so black, like mezzotints.

I was very influenced by Bill Brandt. I knew all his photographs and I went to see him in England. So it was certainly to do with that. And I was lucky to find a guy and I lived with the family. I had Pablo then. It was interesting.

There’s something about the thoroughness of that work that must have come out of the circumstances of its making. It doesn’t seem like a quick body of work.

I lived with another family and then I went to photograph him and he was a very nice man. These Welsh people. Somehow I liked the difficulty and the cold. They were really, really poor. Mabou is luxury compared to how he lived.

Didn’t you say at one point, “I like difficulty and difficulty seems to like me?”

Maybe it’s more about chaos. I like a certain disorder; then I can find something in it. I’m like the crows who pick food out of the garbage. They get the good pieces. You don’t have to go the easy way and there are no shortcuts. I don’t believe there are shortcuts so maybe that has to do with the difficulty.

Is it a question of putting resistances in your way? Do you consciously search out contexts or situations in which those difficulties would be guaranteed?

Making films is that way. The only film that I didn’t succeed in finishing was with those two women in Cairo. I knew it would be difficult. Usually I persevere and can manage, by a hair, to save the whole thing and put something together. But this time it was too much . . The two women…

Was it because of them that it was too much?

Yeah. It wasn’t because of Egypt, it wasn’t because of Arabs, it wasn’t because of “the Jew.” It was simply the two women.

Do you know the lines from Yeats, “‘Tis certain that fine women eat a crazy salad with their meat , whereby the horn of plenty is undone.” You got caught inside a Yeats poem.

Well, it was a good experience. But people that are beset by their own difficulties have a hard time putting together what they want to put together. I don’t mean materially. The guy that I made this film for was a very rich man. Not just money but endless amounts of money. He was totally insane, but I was fascinated by this guy who was so untalented and who would go around the world making a film for millions of dollars. He was an impossible man. He still calls me sometimes. But it was complete insanity. I don’t think he knew who he was. It was comparable to the Rolling Stones tour that was also about money and power. But with the Stones there was talent, there was a performance—despite all the dope, there was some kind of normality.

I’ve got a question about Cocksucker Blues. Those scenes on the plane are pretty wild and it occurs to me that some of them were orchestrated. Were they set up or were you just present as a documentarian?

They really didn’t want me to make the film. They enjoyed having us around but not to film. I was with my friend Danny and he had good connections for dope, much better than they had. And at one point I said to him nothing ever happens on these plane trips. It would be nice to have something happen.

So you were a director then, not just a shadow?

That was one of the few things I said in all the time we spent on the plane. When the film came out the Stones agreed not to cut anything, although I had to cut some things with the officials from the record company. That’s what adds up; your experiences. Making a film is an experience really; more so than going around photographing. Making a film is a real trip.

But Cocksucker Blues is a pretty amazing film. It’s an inside look at a world that nobody ever gets inside. At least at that time I don’t think anybody did.

It’s a most difficult thing to do, to try to show how they are. It’s kind of a sad world. Once the performance is over it’s a downer, no matter what.

That image of Keith Richards literally falling over because he’s so ripped is both hilarious and tragic.

But there’s not a moment when Jagger’s not in control. And they’re ruthless in their control. But it was wonderful to do it.

So, you’re not going to call them and ask to go on the Bridges to Babylon tour?

Well, it’s probably not so wild now.

At one point you asked yourself the question, “Am I too old to be a rebel?” I guess the question could still be asked about the Rolling Stones?

I think it’s okay. They have such a big name, such a big following, why shouldn’t they tour? Maybe that’s his goal: to go longer than anybody else and be in The Guinness Book of Records.

I was surprised to find out that Pull My Daisy started out as a project for Zero Mostel.

Zero Mostel was a friend of mine and he said he would do a film but it didn’t work out. And then Kerouac had the third act of his play. When I went to his house in Northport he read the play, taking the different tones of all the characters. He was really wonderful. So I said, “We can do a film like this.”

But it wasn’t a one-take improvise was it? It’s too carefully structured to have been done just once and recorded.

It was a good mixture. Sometimes you just had the camera there and you would get little glimpses of what people were doing, and other things-like the tour around the table-were structured. And .then we put in the scene outside. I remember the scene when Gregory [Corso] sits on the floor with Allen and they talk about Apollinaire and poetry. They just sit there. Something is very funny about it but it’s too serious so then somebody in the back took off their pants. You shot a lot then, there was a tremendous amount of footage. I worked a long time on the editing. And it really fit together because of the narration by Kerouac which I thought was a masterpiece.

One of the things that is not commented on much is the humour in your work. I think it’s often very funny. But in those early years it looked like everybody was having a helluva good time. Pull My Daisy is full of joy.

Yeah, it was a good group. And it was a new experience. I mean we all got together in this room and tried to make this film. You believed it was going to be a great thing. And it was relatively unplanned; we had Wild West scenes with cowboys and with shooting. But the characters were good, I mean Larry Rivers was good, Amram was good. Too bad I had a terrible fight with [Alfred] Leslie which still goes on. He wanted to change the film and I didn’t want to change it. A partnership in film is one of the hardest things for a friendship to survive. There’s so much ego involved. It happened in Candy Mountain with my friend Rudy Wurlitzer. He thought I took over. One has to be always a little bit stronger than the other. It touches on so many raw nerves in the relationship between two people. It’s hard. You better be brothers. I would have liked the film much better if I would have been permitted to be freer, like in my other films. But the machinery of making a movie was much stronger than I was. It just rolled over me like a steamroller.

Was Candy Mountain a more ambitious film than anything you’d done before?

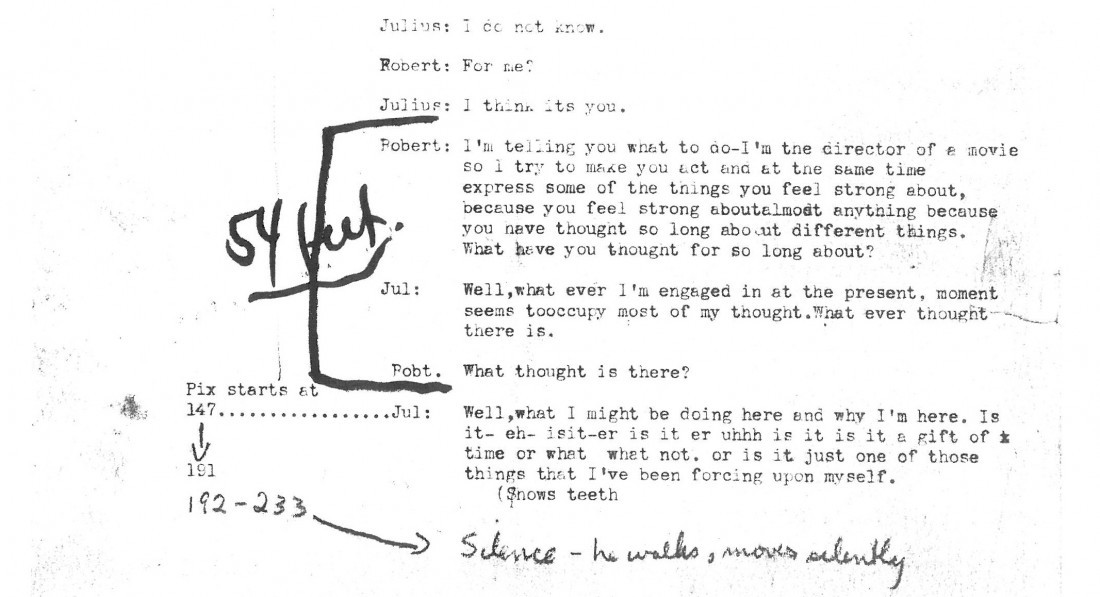

Transcript of dialogue between Julius Orlovsky and Robert Frank from Me and My Brother.

Well, I had never done anything that had so much money involved. And it was ambitious in terms of wanting to make a record and with all the music in it.

Even though it was Rudy’s script he continues what you’ve always done in your films and that is to tell stories that are autobiographical. I can’t help but see Elmore Silk as your surrogate. He’s a guy who cuts out, who goes to the end of the road and who people seek out.

Yeah, but that’s not enough to make a good film, just a little story.

I liked the film in the way I like Down By Law. It has a real intelligence about it, a kind of odd quirkiness. It always surprises you.

I didn’t feel like that about it. It’s my least favourite film in terms of adventure in filmmaking or expressing something in a unique way. It was much too conventional for me. But at that time I was happy to make it. I did another one with Rudy on Wolf Island here; it’s a little film called Keep Busy. I liked that a lot. It’s more how I look at life. It has a certain disaster and disorder and chaotic-ness and insanity. Everything is upside down.

Isn’t it Rimbaud who says, “the poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious and rational disordering of all the senses?”

Well, they are not new ideas, but as an artist you should have the courage to put that in your work or to try to write it down or preserve it. And I think often artists today make concessions to survive economically. Candy Mountain, all the way from the beginning to the end, was a concession . It was too painstaking a thing to do, it took too long to set it up. There were little kids around who I wanted to get in. But I was told I couldn’t because of the union. There were a lot of people involved in it: French money, Canadian money, money from America. It was complicated.

Is Conversations in Vermont which you made in 1969, apart from your new film , still your favourite? You said it was the one that was the most honest.

Well, it’s too painful really to see. I liked best maybe Life Dances On… and The Present. The Present is the most spontaneous and it’s something that you can do only once.

Do you mean you wouldn’t get it again even if you wanted to?

Even if I had all the money and all the support. That was truly seizing the moment and using it and then waiting. It’s like fishing. You sit there for days, and there’s nothing. They played it at the New York Film Festival and they asked me for a statement at that time. They made a film from the video and it came out very, very good. The quality was absolutely amazing. Anyway, here’s the statement:

To use the camera with intuition, to be ready for improvisation , to keep the moment in mind inside and outside the present.

That inside and outside thing comes up all the time. Was it Julius Orlovsky who first mentions it?

Probably. He said amazing things at the end of the film. Of course it’s also in the photography because he looks out the window. But you’re very observant. I never thought of it but it probably came there. He was amazing.

When he says that the camera seems like a reflection of disappointment or disgust and that it’s not helpful in disclosing any real truth that might exist—as difficult as it is for him to get it out—you gasp because he’s gone to the centre of the film. What was the moment like when you saw it behind the camera?

Well, you’re so busy with the camera and the sound. This was a difficult movie to make. All movies are but you are more concerned in trying to get the picture right, get all the technicalities straightened out. So I didn’t realize how amazing it was until 1 saw it typed out. I’m trying to make a little book with it. I intend to bring out the film in video.

You said you think the film was half an hour too long. Are you going to edit it?

I took out maybe 15 minutes but it’s hard. I worked on it just a few months ago and now it’s ready to be made into a video.

You talked earlier about how you learned rhythm from the kind of sequencing that you were doing in film. How do you decide how long a story takes to tell?

An editor has a lot to do with it. That film I edited myself, so I don’t think you are the best judge of that. Usually, you let it go; I mean I let it go. I don’t go back to my photographs and make another book from the out-takes of The Americans. I don’t replace a picture I don’t like. With film it’s the same. It’s very painful for me to see these films because when the bad five minutes comes up it looks like half an hour. But I never took anything out except in Me and My Brother, I thought the whole film was just too long. I could have taken out more. In The Present, I had a wonderful editor, a young woman. She was just very astute. I explained to her what I wanted and how the film was made and how I wanted to preserve it. There’s a scene in Zurich: I’m in the hotel room waiting for my brother and the camera is on the empty television set while I explain what he does, what his wife does. It’s kind of a put-down, I don’t get along very well with my brother. And then he comes and he’s very nice and we sit there and I ask him questions. After she edited it, I said, “Where’s my brother?” She had cut it all out, but the thing with the television was in. She said, “I couldn’t understand him anyhow. He’s kind of weird, he talks German.” You could never do that as a filmmaker. I set it up and I want to see my brother. But it’s not necessary to see him. These are the things that you don’t have the strength to do yourself. But it’s absolutely necessary.

Is film more forgiving than still photography? You can have five bad minutes in a film but the structure will carry it. Whereas in stilt photography every single image seems to count.

It’s unforgiving for film because it comes up and it runs the same way. If you have bad pictures in a book you can just flip the page, you don’t have to read it. But with a film the people are there, they have to see this. That’s one of the reasons why I can’t watch my films.

I want to ask you a couple of brief questions about sequencing. How carefully do you plan the visual resonances that seem to turn up repeatedly in your work?

In The Americans I was very careful, I really wanted it right. After that I never cared that much about it except in The Lines of My Hand.

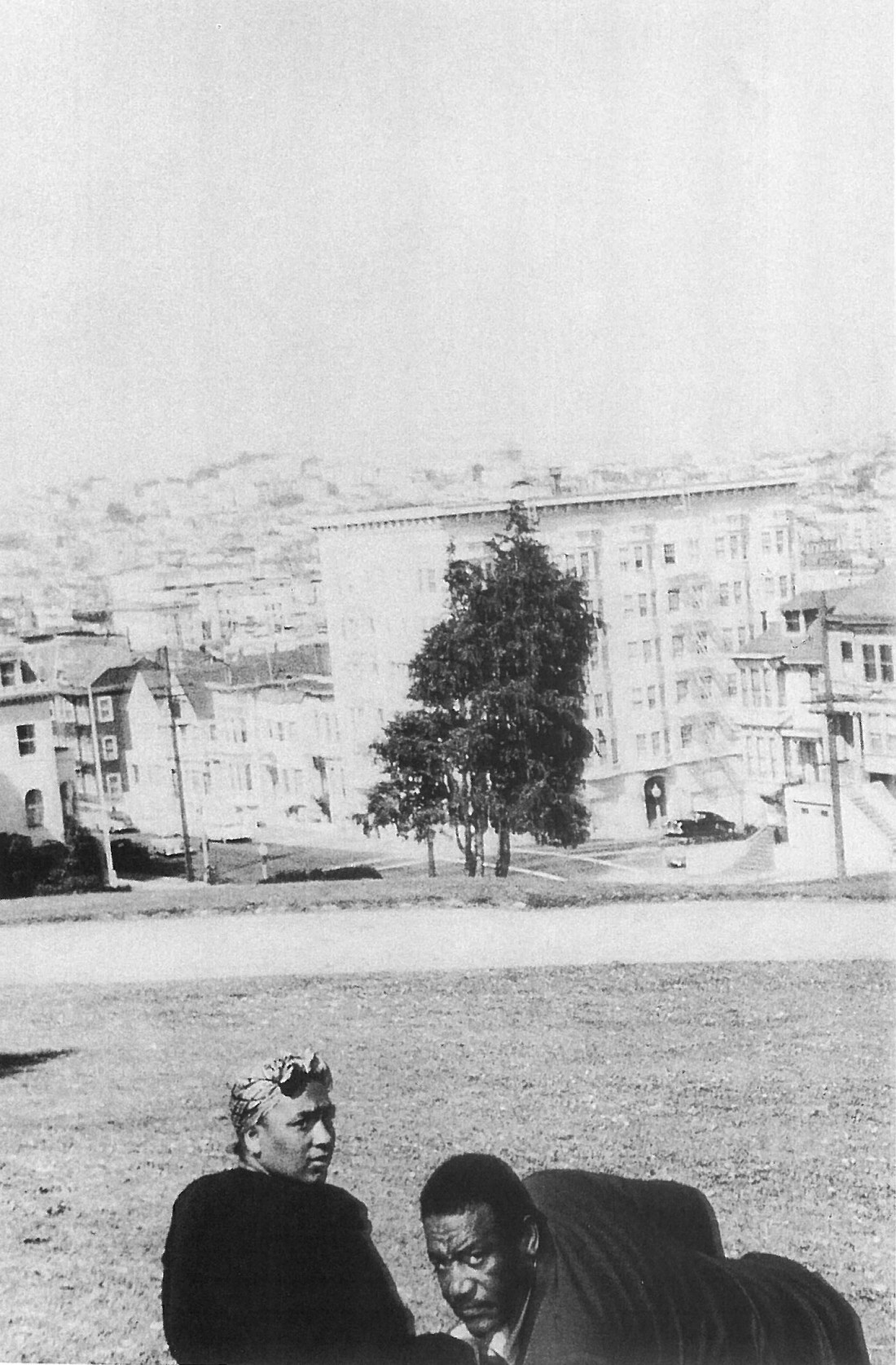

San Francisco, 1955-1956 from The Americans.

In the Pantheon version did you let the editor do the organization? And what about in the Lustrum edition done in 1972?

That was pretty much my sequencing. And also in the Pantheon version. But I wasn’t insistent because I saw it could go many different ways. The Japanese edition was different from the Lustrum edition, so now the Pantheon edition would be different. In this recent Flamingo book, I said I want to have these pictures in the show and these pictures I want published in a catalogue.

I sensed in looking at the 1972 version of The Lines of My Hand that it’s a more emotional book than the Pantheon edition which seemed harder. There were also more images in that ‘72 version.

It’s less polished. It’s also yellow. It’s like wine you know; it gets better as it gets older. It was more primitive and had a directness. The other version is a very classy book of photographs. They’re set clean, each one is a little jewel. Maybe these photographs don’t lend themselves so much to that.

Sometimes I think the way you combine images reflects an emotional logic as much as a pictorial one. Is that an important side of your photography?

Now it is because it’s all turned inwards. I watch myself, I watch what I’m doing here, “Why the hell am I here, what’s so great about this nature boy?” So you have to examine yourself. I wish Julius would be here putting it in the right perspective. Yeah, you question. That’s why yesterday I did a picture looking for my roots. Am I here trying to get roots? Is this it? At 70 maybe you should know where they are, but if you don’t know maybe you were a very lucky fellow.

Are you saying it should matter to you? Or does it matter emotionally?

Towards the end of your life it will matter emotionally. Before it wouldn’t bother me. Now you begin to think like your father, you begin to think about the criminally ill Swiss, you think about where you come from. Because I know where I’m going.

Do you?

Pretty much.

The reason I sound a bit incredulous is because one of the consistent characteristics of your work has been the constant search and the recognition that there may not be answers.

Work is one thing. Work is a byproduct of the hopping around. But the work can surprise me. I have a wonderful story about a totally unexpected thing that happened in my life. In the late ’50s I met a Chinese painter who lived in France but who wanted to come to New York. I would give him my studio, he would give me his in Paris. This was before I was married. Anyhow the guy had no money and I liked him a lot. He was a wonderful man and I always thought he was a good painter. But he was disenchanted, he could live without anybody. He made no compromises. He lived that way even when he was at my place. He was a very unusual guy, about 20 years older. When I went to Paris I would always go to his place. Then when he was 65 I went and the door was locked. The concierge said he died and all his stuff was thrown out. Then a woman calls me up from Sotheby Taiwan—she came here last week—it turns out the guy became the most famous new Chinese painter. He’s the one. So, all his paintings are worth tremendous amounts of money. He painted lots of animals and I had many of these paintings. So I sold them. They made a nice catalogue and in October there’s an auction. And I think of this man living, not believing, and he stopped painting after awhile. He was very alone and it was sad to see him. I’d like to make a little film in some way about that story.

Had you filmed Sanyo when he was alive?

I took photographs. They put them in the catalogue. It’s absolutely amazing thinking about him, how I tried to help him in Paris, I had relatives in France and they had money and they would offer him a typewriter in exchange for a painting. I think he committed suicide in the end. He was just so alone. He had difficulty communicating, his French was barely understandable. When he was in New York he would sit in the movies for three, four, five hours, buy cheap booze. He was a wonderful man. I learned a lot from him. I’m not so interested in showing his paintings but I’m interested in how I am a winner in this. He left the paintings with me and there’s no other relatives in China that they can find. It makes you think what turns are done in life. I’d like to make the film a little bit funny.

I often sense ambiguities about how to read the films. Is that a reflection of how you yourself view life?

I’m not a great storyteller. Sometimes, especially today, I often feel there’s too much information coming anyhow. So I want to deal with less information and replace it with, you know, corn flakes. Think of it as cooking, what you cook up in a film, what you throw in. It can lead to disaster but it also can lead to something interesting. I think Me and My Brother has a lot of that. It searches and suddenly comes up with a very good sequence. Then it goes meandering on. But life is often like that. So I make these films and I hope that they’ll be seen but I’m not interested in having a million viewers. I don’t even care that much if it goes on television. But it’s interesting for me that you can do just video and you can blow it up and it can be as good as a film.

Do you make the films for yourself then? Have you always made the work for yourself?

In the beginning I had to hassle to get money for them because it was something that you had to do because you were here, you wanted to do this story on the island or with my children. Or get some money to make a film about music. But then your personal life creeps in. It’s so close. The painter is not that close with the imagery. With film you turn around and see yourself in the mirror—it’s your house, it’s your road. It has a reality that often is embarrassing and you try to wipe it away. It’s too much.

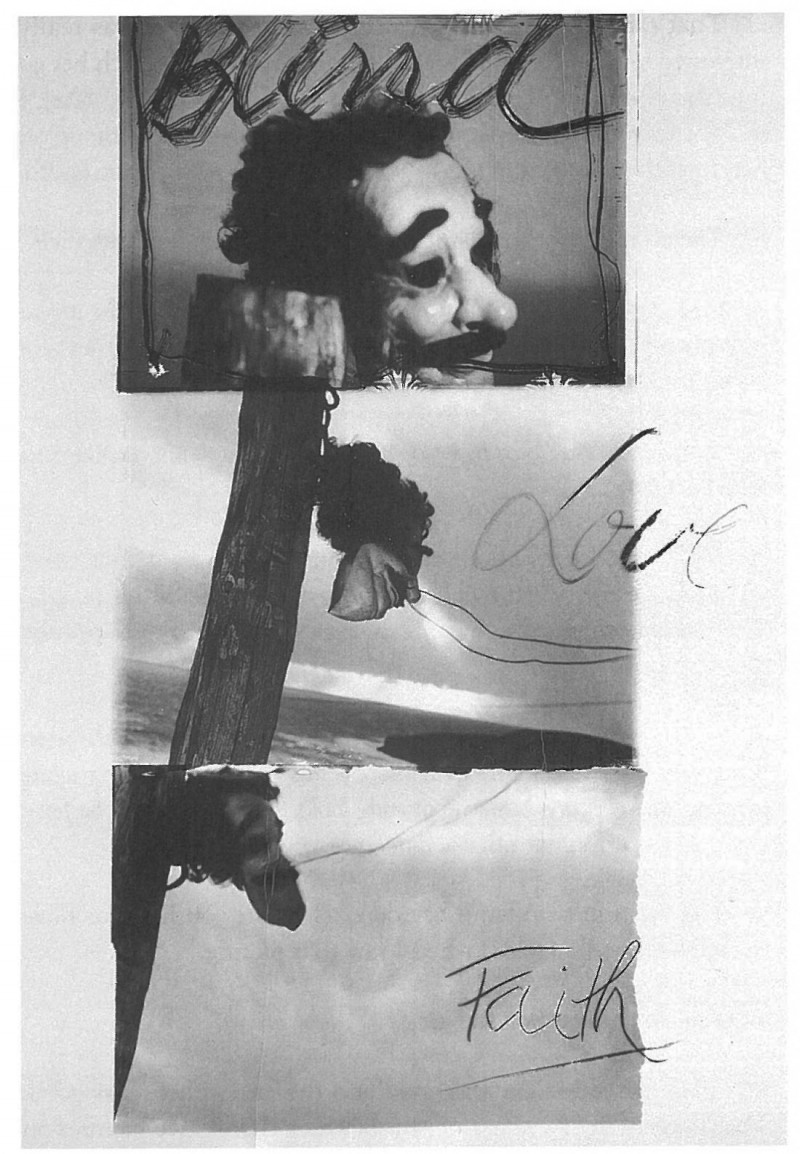

But you’ve never shied away from getting those things on film that could be painful or that could make you vulnerable. I’m astonished sometimes at the combination of vulnerability and aggression in your films.

Blind/Love/Faith, 1981.

You try to be truthful and it’s easiest to be truthful about yourself, if you know how much you want to give away of that truth. You don’t know that about anybody else. So with actors I have a hard time. It’s difficult for me to communicate how I want them to be. I don’t have the directorial will to push and be aggressive.

But you’ve been quite straightforward in admitting you have no regard for anyone who happens to come in front of your camera, that they become stuff for your vision at that point.

I think that’s pretty true. They become actors and I also am an actor. I try to give a good part of myself to this acting.

In Conversations in Vermont you say you go out to confront your children and yourself. That’s one of the most difficult films for the viewer to watch. It’s relentless.

Many people say that they are amazed that I do it. It shows something about my character—above or below tolerable behaviour. Maybe with what I know now I certainly wouldn’t make a film like that again.

But at the time was it about being in the experience and trying to understand your relationship to your children and they to you?

Yeah. It was also at the time when you knew they weren’t children any more, when they would move away from you and go on their own way.

The whole question about how we use the people we care for as material for art or writing is complicated. It comes up with Sally Mann and the way she’s used her children as subjects of photography. She clearly had few limits on what she would do with them. I’m raising her as an example of a degree of relentlessness that makes some people uncomfortable.

I think if you get people to give that much away of themselves— whether they’re children or not—then it is justified. Diane Arbus certainly portrayed people ruthlessly. Maybe it’s too much a question of the end justifying the means. People have often asked me—younger people—when you go around travelling don’t you feel bad that you take pictures of people and publish them. Probably today I wouldn’t do it like this, I would talk more to people. Then it was just quick shooting. I never got any letters out of The Americans from people who complained about their picture being taken, except one. The photograph of the motorcycle with two guys standing there. A girl writes to me and says this guy is my boyfriend and he’s in jail now, I’d like to get some money. I think I sent them $50.00. That’s the only communication I had from The Americans.

I think of that wonderful photograph in the bar in Mexico which is shot very low down. It occurs to me that you couldn’t just pull out a Leica in that environment and begin shooting. You must have been both surreptitious and nervous.

Of course, you don’t go in there and take a camera out. You have to know my favourite picture in The Americans is of the black couple in San Francisco. Because just as I took the picture the guy looks back and I saw him in the viewfinder and so I slowly turned and took another picture away from him. He kept on looking.

It’s got a real edge doesn’t it?

Yeah. It’s what you face as a photographer all the time. You’re like a cop watching people, observing them, stealing.

My favourite picture in The Americans is the view through the hotel window in Butte, Montana. Did you know they were great images when you were taking them?

Sometimes I had an idea that it would work out. Sometimes you can be surprised. But sometimes you know: like with the black couple. I thought it would be very good with the city in the back and the sky, the whiteness of the city, the blackness of the people.

There are a number of good photographs of couples in The Americans. Were you aware that you were getting an amorous side to American life that had its darker implications as well? I’m thinking of that beautiful couple in Reno, Nevada. They are just so sexy and in love.

That’s a good story. They just got married and I was really interested in them, a good-looking couple. And then I watch her go into the phone booth and she calls up and I hear her say, “Dad, I just got married”; a couple of more words and then he hung up on her. I got the photograph just before she went into the phone booth.

There’s also some wonderful images of America in love with itself.

Yeah, I never thought it was so anti-American, I thought it was interesting that the black people simply looked better; they are better looking people.

And there seems to be more joy in their world. Is that something you found in doing it?

No, I found it in photographing, in travelling. At that time, the black people were much more open than the white people. They were totally open and not suspicious. It probably would be different now.

In looking at the trolley in New Orleans you actually see the wistfulness of the black man; then there’s this ferocious looking white woman, and a young boy who already looks like he’s going to be ferocious. It’s a perfect narrative of difference.

You pick up wonderful accidents. I mean you have to have open eyes. I was surprised when I saw that picture.

You didn’t know you had it?

Well, the street car was good and the atmosphere was good. That’s one of the rare contact sheets where there’s two pictures on the same contact sheet. That must have happened within five minutes. There was a Woolworth’s Store across the street and its marquee is reflected.

I have a question about Black, White and Things. When you first did that book it was just three copies , one for your parents, one for you and the other … ?

I gave one to Steichen.

So it was like a livre d’artiste.

Yeah. I did it with my friend who also worked on The Lines of My Hand. He just died a year ago. Which is another thing that happens when you get older; you become more alone. Ginsberg meant a lot to me. I saw him just the night before he died. He came to visit me often, so I went over and sat with him in his new apartment. He was very proud of it. He always wanted to give me books and there was this one book he made with Larry Rivers. He wrote with a very shaky hand, “To Robert Frank on his first visit to my new studio. Where I am inspired to expire. Ahhh …. ” So it’s quite amazing that he wrote that. It was very touching how he was. It made me very sad. He was really much nicer to me than I was to him. He was a good man and he suffered a lot. It shook me up.

I want to ask you about memory. Is memory ongoing for you, or is it a static thing? Because so much of your current work reconfigures earlier work and the same issues keep coming up. Is that because your memory is so persistent?

No, my memory is flying away. I have less and less of it. But photography is memory anyhow; it becomes memory right away. When you make a photograph, it’s already gone. This is how you remember. You remember people by photographs. I really try not to but they slip in sometimes, these photographs. The best thing would be to leave no future, no past. Just be now.

The eternal present do you mean?

To work in that. I think June works more like that.

But your work is loaded with memory, with care for those people who are lost, with trying to understand the complications of your emotionallife. There’s not a single image you’ve made in the last 20 years that’s about anything other than that.

Well, it’s all lying around. Here’s a good one. I don’t know if you still can read it. “Everything I made will fade.” I’m reassured by that. Chester Pelkey wrote me a letter and on it was a Flannery O’Connor quote from Wine Blood: “Where you came from is gone, where you thought you were going to never was there, and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.” It’s an absolutely wonderful quote about life. When I made Moving Out this was the only quote I wanted to leave in the section that now is called “About Fate.” And the woman from the National Gallery tried to get permission from the estate and they wouldn’t do it. And they were very adamant about it; they wouldn’t even let me quote one line from it. Yeah, memory. Well, you can’t get rid of it.

And don’t want to, I assume?

Oh, I would like to get rid of it but it’s lying around.

You would prefer to unencumber yourself, to unlearn your past just like you unlearned technique?

I would like that the past wouldn’t follow me. But what would you do without memory?

You say that, by its very nature, photography is fleeting. Is the work, then, a way of fixing something?

Absolutely. You get this idea and you try to make something as soon as possible. And then you can build on it and put it between other things that you find in this closet. Wherever you look, it’s another piece of something from a long time ago. I want to get rid of it but it all comes out. I don’t want sentimentality in my work. I don’t want it to be sentimental, that’s self-pitying.

And is that something you consciously work to get rid of in the work?

Yeah. My concept is not to be sentimental. In film an editor can help. I’m not aware how sentimental are certain things I’ve done. I can be an editor of my photographs. It’s much easier than editing films. Photographs are easy to discard. You see it right away.

One of the photographs I think is extraordinary is one of Kerouac obscurred by a line of flamingos which is reflected from a window somewhere. How was the photograph made?

Two negatives put on top of one another. It was much later when he had died. Maybe not, I’m not sure. But it was from the trip to Florida. With this Flamingo show which just came out, I asked a friend of mine who lives in Florida if she could get me a neck-tie or something with a flamingo on it to bring to the people in Sweden. She didn’t find anything. There are no more neckties with flamingos, no shirts.

Still from The Present, 1996.

It’s a tremendous loss to fashion isn’t it? But how did the flamingo get inside the bottle you used for the newest flamingo photograph?

Actually, these were bottles my son used to make and he planted in it. The plant died, then I had that flamingo and I put it in the bottle. It’s cut at the bottom because they were sort of terrariums.

I’d look at that bottle and dismiss it. You turn it into one of the most affective photographs in the new catalogue. Do you now have an instinct for what will work, or are you still guessing?

If you don’t have it by now, then forget it. Intuition and instinct, that would be what I work with. I mean that pulls my wagon more than the concept. I have to have it. It’s essential.

The poet Ezra Pound had the idea that only emotion endures. Looking at your work I get a strong feeling that it’s something you would commit to as well.

You believe it will endure and you believe that you can live with it. You can get it out and it will endure that way. But often in films I hear myself talking or I write down something an actor will say. I listen to it and say, “What kind of shit, how can you get away with saying something like that. It doesn’t work.” I mean I don’t believe in it. But I do believe in the photographs, I know my instinct is right. I can write letters to somebody that go from me to you because I imagine the person it’s going to. So it works that way. But to go out to the public and have these lines is hard.

I love that section where the newspapers are blowing on Bleeker Street and you’re looking down from your loft window. You remember Kerouac saying that fame is newspapers blowing down the street. It’s a poignant, wonderful moment in the film.

Memory again.

Exactly.

Now I really have to come up with more because mine is fading away. I don’t have a good memory of things that I read. It goes away.

So if you have your world around you then you’re constantly being stimulated by your past aren’t you? This room is like the imagination in a way. It’s all here.

What’s good here is a lot of what’s in The Present. Living here, June working over there, getting ready for the winter, then I’m travelling to New York and coming back here. I don’t sit here to think about the past, but when I work it comes in.

What is the thing you have about framing? It happens a lot—words and images are framed , on the clothes line or looking out the window. And that impulse goes way back—I’m thinking of that photograph of the back door of a hearse open in London where you framed the figure inside the window of the door.

You have to have a quick eye. You have to anticipate what’s going to happen: the girl is going to run. I think you can learn by practising a lot, by photographing and looking at your photographs. But you can’t really teach somebody to see it right away. Because life moves very quick.

And does it please you when you get it? When you looked at the London hearse did you see what you were getting?

When I took it I knew-that’s a good picture. But I’m not interested in that any more.

Now that you’re constructing images does it give you more security in knowing what you’re going to get, or less?

You have the same measurement, the same eyes. Maybe you’re even more critical because if you construct something it’s very easy to be phony, and you make more room for humour or for the ridiculous or for mystery. You make room for that; it replaces something else from these moments in life that are memorable.

And even quotidien. It’s the everyday that you’ve been able to elevate to the level of the memorable. So much of what’s here wouldn’t seem significant except for the attention you pay it.

Steichen used to have these stories about himself, old Captain Steichen of the U.S. Navy. Well, Captain Steichen had a good garden with lilies and wonderful flowers he’d cultivated. It’s very famous. He photographed a cherry tree in the fall and the blossoms in the spring. I hope I never end up photographing the cherry tree. I still feel that way. I don’t want to photograph the seasons, it’s sentimental.

You’ve just photographed the seasons and it doesn’t look anything like a cherry tree. You did a four-part image called Mabou, Nova Scotia that has June lying in the foreground of the “west” quadrant.

That was the seasons here. Well look at the film The Present. It contains a lot of what we’ve talked about. I’m very happy with that film. June is very, very good in it. It doesn’t say that much but it’s very good to be able to take everyday life: she does the laundry. But the best moment in the film is when I photographed her dirty hand with a penny in the middle. It’s a wonderful image, this hand just holding the penny.

You say that the truth is outside and you realize the outside is constantly changing, which is to say there is no truth. That strikes me as being a very frustrating position to find yourself in. Is that so?

Well the film in Egypt didn’t work because you had to reveal more of people’s feelings towards each other. And I find it’s very hard. Everybody had something to hide.

Is your job as a filmmaker to make those things unhidden? Are you unmasking the veils that people place over themselves?

If two or three or even one person agrees to work with me on something, I would expect it. But then all of a sudden you feel that you yourself are not really quite ready. And that’s shipwreck, that’s when the winds are blowing too hard. But if you’ re inventive you can still do something. I did it simply by putting these pictures in Moving Out at the end.

The instruction to “Keep going.”

It is very important to continue. You have to continue and you have to set yourself a real high level. You can’t just say, “I’ll continue no matter what, I’ll just write another two pages and take another series of pictures of dead crows or something.” It doesn’t work like that for me. There are really no shortcuts that way. But it’s important to continue.

And still be uncompromising?

You have to be, otherwise it’s crap you do. I don’t want to. I don’t need to. Some people are forced to produce because they have to fill up a space in a museum or they are ambitious. June asked me, “Why do this interview now, what do you need?” I do it because it’s Canada and I like your magazine but I really don’t need an interview like this. I’m out of words almost.

You said something earlier today about there being no more heroes. I’m not trying to flatter you in saying this, but every photographer I’ve talked to sees you in precisely that position.

Yeah because as a rule photographers are cowards. They’re ordinary, they’re schleps. They have no high standards because it’s too easy to photograph. It’s sad because I often feel that respect from people and it takes away something.

What do you mean?

It makes it difficult, there’s so much distance. Although I get wonderful letters, little images people send me of photographers that are earnestly trying to express themselves.

So I won’t saddle you with the heroic label?

I am surprised how many people have such a high opinion of my work.•