Doing Just the Right Wrong Thing

An Interview with Tom Sachs

Tom Sachs is the Lenny Bruce of contemporary American art: uncompromising, wickedly funny and whiplash smart. His gift is the production of incommensurate hybrids, things which make connections that end up being not just funny, but somehow inevitable. These combinations take the form of objects, installations and architectures; in his “Nutsy’s” project he links a McDonald’s drive-through with buildings by Le Corbusier, including the Villa Savoye and Unité d’Habitation, the massive apartment block built in Marseilles in 1952. The structures are made from Foamcore, Bristol board, thermal adhesive, resin and Wite-Out and produced in a scale of 1:25.

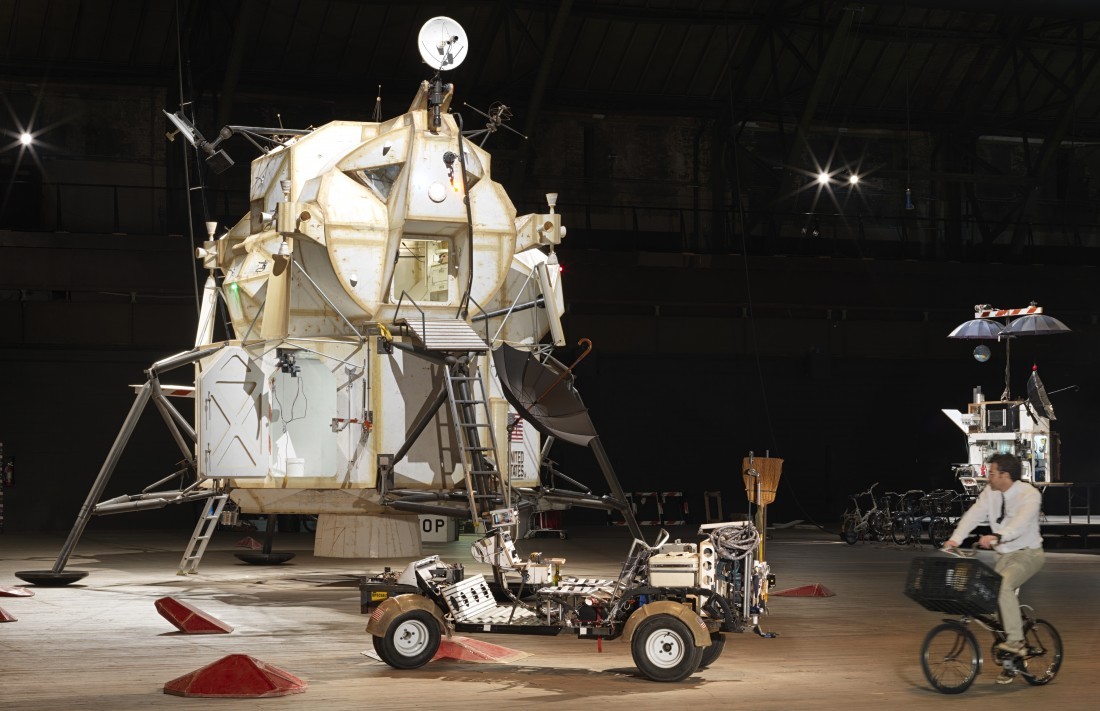

They are paradoxically awkward and absolutely convincing. In his major installation at the Fondazione Prada in Milan in 2006, he installed in the same cavernous space a life-size blue whale, a customized 1989 Chevrolet Caprice police cruiser, and a one-story high model of the superstructure of the USS Enterprise, America’s most famous aircraft carrier. It was an improbable and ingenious combination.

Tom Sachs, Space Program: Mars, installation shot, 2012. Photograph: James Ewing. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

Sachs plays in a world where high and low commingle; if you negotiate the racecourse that makes up Nutsy’s you have the choice of driving through the ghetto or the modernist art park. The former is a wasteland of garbage, overturned dumpsters and scattered beer bottles; the park provides models of iconic sculptures by David Smith, Alexander Calder, Claes Oldenburg and Constantin Brâncuși. The Romanian sculptor is represented by his famous Endless Column, a sculpture that Sachs has variously realized over the last 10 years, including a black version made from McDonald’s containers and a white one composed of NYNEX calling cards. His imagination draws from both art and popular culture. “When I was at Barneys, I learned that my sculptures aren’t competing with Jasper Johns,” he says, recalling a lesson picked up as a window dresser in New York, “they’re competing with a pair of Air Jordans.”

Sachs is particularly adept at making familiar objects from unconventional materials: a cinderblock from epoxy resin, steel and latex paint on plywood; a Mondrian painting from coloured duct tape; an Elmhurst Dairy milk carton cast in silicon bronze; the observation tower at LaGuardia from fir plywood; a stacked columnar sculpture from bronzed and patinated DieHard batteries; a Hasselblad camera from pyrography, thermal adhesive and barrier wood; a series of McDonald’s value meals in the colours of Hermes and Tiffany’s. He has used these luxury brands and their signature palettes to fabricate some of his most provocative sculptures, including a combined guillotine and breakfast nook “by Chanel,” a board game called Prada Death Camp, and a three-part collection called Giftgas Giftset, in which products labelled Zyklon B are displayed in cans coloured in Chanel black, Hermes intense orange and the delicate blue of Tiffany & Co.

The links he has established between high-end consumer culture and the violent history of the 20th century, particularly the Holocaust, is the area in which Sachs has generated the most controversy. He responded to that criticism in an essay called Barbie Slave Ship, published in 2013 for the 12th Biennale de Lyon, in an edition of 200 copies. (The essay can also be found on the artist’s website). The fact that he included it in a zine about a work which places 324 bound Barbie Dolls in the hold of a slave ship is an indication that separating the boy from his irreverence promises to be a formidable task. Barbie herself is one of the slaves listed in the ship’s manifest, along with a sisterhood that includes Halle Berry, Mother Theresa, Miss Piggy and Pussy Riot. Sachs doesn’t undertake work of this kind lightly; the research he conducted into the European Homogenocene before making the model of the slave ship was thorough. As he says in the following interview, the ground he is standing on is made firmer the more he learns about his subject.

What links his promiscuous objects is the process of their making. Sachs is a hands-on kind of artist, whether he’s burning the space around a spider web onto wood, replicating the furniture from the 1937 Barcelona Pavilion out of Foamcore, steel and plywood, or directing an earthbound moon landing from a bicycle. What he resists in fabricating his world are the perfectly-made objects of contemporary culture. He champions an error-ridden aesthetic in which finish is replaced by another look: glue, drips, chipped wood and cum stains. For him “flawed is the highest value.”

It would be a mistake to think that his work is easily made. The spider web is the single object that stands in for all the objects he has produced. He admits he could draw the same web in a couple of hours, but putting 2000 hours into it using the technique of pryrography produces a fundamentally different piece. “My way of seeking out a way to a clearing,” he says, “has been through the ritual of work.” In saying this, a mischievous smile crosses his face. “Isn’t it written somewhere that work makes you free?”

The following interview was conducted by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh in Tom Sachs’s New York studio on February 16, 2014.

Spread from Tea Garden Workbook, (zine, 2014, 2nd edition, 50 copies). Photograph: courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

Tom Sachs: After I graduated all my friends went to graduate school and I did window display at Barney’s where my teachers were the most ruthlessly demanding queens. They had impeccable taste and sense of style and no hair could be out of place. They said if your art isn’t good looking, no one is going to look at it. The generation I come from has a kind of disdain for beauty and a lot of good artists whose work I really love, like Rachel Harrison and Jason Rhoades, are dealing with interesting ideas but neither of them would brag about how pretty their things looked. And that’s important to me. My mom taught me that if your art doesn’t look good, when you die they’re going to throw it away. There is also a very strong link to the teaching methodology of the Bauhaus here. At one time my main ancestor was David Smith, but now it is the Eames Studio. People say that Ray brought the intuitive to the table. My studio’s movies are made in the manner of the Eames Studio’s movies. I’m trying to hybridize and channel intuition using some industrial design strategies. Because in Ten Bullets, we always say creativity is the enemy; do what is set out before you. I believe that. But the secret formula is to trust your intuition enough to know when to do just the right wrong thing. People confuse that with creativity. You only need a little bit of inspiration and then a whole shit ton of work to make it come to life and be real.

Border Crossings: It’s interesting that you mention David Smith because you still show the welds in your work. You are happy to show evidence of the mechanics of its making.

Absolutely. And it is important because we are living in a time of perfectly made objects. You look at your phone and your tape recorder and your glasses and there is no evidence that they were made because all human touch has been erased. I don’t think an artist can compete with Apple, and Apple can never show something with glue and drips and chipped wood and cum stains, the errors that I can provide. So it would be very easy to blob a little white paint and you would never see the repair where we have a different screw going in, but leaving it gives an additional layer. I was talking to someone yesterday who was writing an article about ceramics and he was asking why ceramics are coming back. I think it is a reaction against how perfect our iPhones are. Even though it sounds expensive at $600, that machine provides an incredible value because it is only pennies per use cost. I think the pendulum is swinging towards the handmade and there is nothing more evidently about craft than ceramics. It has your fingerprints all over it and when you see my things you’ll see that I don’t fuck with the potter’s wheel. Mine are very flawed and to me that is the highest value. Beauty is so subjective.

I’m thinking of your mother’s sense that no one will remember your work if it isn’t beautiful. There must be some movement between subjectivity and an objective evaluation.

Yes. I call that style and it’s a very slippery subject. Style becomes an expression of the individual and knowing when to do just the right wrong thing. Style is finding that right place. Marcel Duchamp called this the “Art Coefficient.”

How much Realism is too much; how close do you want to get to a mimetic ideal of any of the things you make? You had your SONY Outsider fabricated and you realized that your things had to be handmade, that you had to be involved in their making.

It was even worse than that. I walked into the boatyard two hours north of here and I was watching them paint with an industrial spray gun over all the beautifully hand applied layers of mottled coloured fibreglass. I had the idea and I had to follow through. Number six in Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art is once an idea is started you have to follow it to its logical conclusion, otherwise you will end up with the same result as the previous experiment.

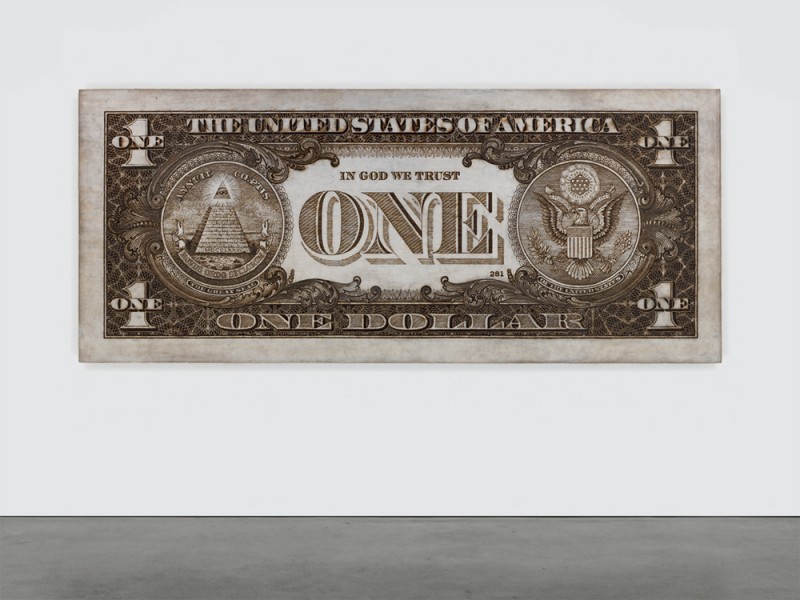

One, 2013, pyrography on plywood, 48 x 113 x 5 inches. Photograph: Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris.

The USS Enterprise is intensely realized, certainly more than the washroom of Lav A2, your 767 lavatory.

I would disagree. That lavatory piece was small enough that I could address every piece of moulding and seam, whereas the real aircraft carrier is the height of a five-storey building, so it had that many doors and staircases. I was making it so it was a one-storey building that you could walk inside. I was doing all kinds of cheating with scale, and scale representation is one of the most confusing things ever, because proportionally it’s exact but it is also just a one-room little shack. So on the outside it’s to scale and on the inside it corresponds to a different scale. We built it in this room where we are speaking now. It is literally as big as this room less a foot and a half on each side; it went almost up to the ceiling save a foot and a half so that we had space to crawl around and work on it. We cut it into three pieces so that it could get through the door and then it was bolted back together. Everything is built in this room. The Crawler was done here; Chanel Guillotine; the ascent stage of the Lunar Module was built in three pieces in this room. We made it one inch smaller so we could get it out of here. If you look at those things they all have scratches on the side from going through the door. I’m proud of those scratches. The nickname for my team is the “bloody fingers crew.” Things happen; that’s part of the process. There are architectural model-makers, set builders and a lot of other people in the world applying a similar skill set, but they have their own set of problems and rules and ambitions and goals. My program is very much about the ritual of the studio, which I’m always trying to amplify, and which involves the ritual of building the thing and how it’s used. You know: the coffee machine, the bar, the hangout, the round table, sex, cooking. I’m always thinking about those things and never about budget, although there is an intuition about what you can and can’t afford to build.

Is that a conceptual residue? The idea that you set rules for yourself from which you won’t deviate?

It comes from that time. In my first works out of college I was really captivated by Sol LeWitt and Douglas Huebler and guys who had these insanely rigid rules that they established upon arriving in California: the edge and end of Western civilization, where natural laws were being broken. You had aerospace laws being broken by engineers and you had fantasy laws being broken by Hollywood. It was whatever you could dream of. These artists thought to themselves, “So how the fuck am I to make art in the face of that power?” LeWitt, Huebler and John Baldessari sat down and made these incredibly rigid rules under which they could make their art, and compared to Hollywood and the defense industry, they were poetic and beautiful and sensitive and humble. When I left school I found myself in California working as an architectural model-maker where I had physical skills that were way beyond my conceptual awareness. In order for my art to survive, I made up some of my own rules and self-imposed constraints. Eames said, “constraints are not limitations, but guidelines that protect us from the existential abyss.”

Cinderblock, 2009, epoxy resin, steel and latex paint on plywood, 16 x 7.875 x 8 inches. Photograph: Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

What is it about the spider web that has so entranced you?

I think of the studio as a spider’s web. It has always been connected to predatorial sex and capturing and hunting and survival, but it is also the supreme structural material known to us. The web is the ultimate thing—in strength, structure, space frame, flexibility. I have special Nike sneakers made from Vectran, which is 10 times stronger than Kevlar, which is 10 times stronger than nylon. I got it from my friends at NASA but it is not nearly as strong as spider’s web by weight and it’s not nearly as flexible. That’s the thing; Vectran fatigues and will snap easily after a few thousand cycles. This piece takes a person a couple of thousand hours of burning. It’s part of the martial arts aspect of the studio because if you can do this, you can do anything. I’ve had more than one person in the studio give me their Adderall prescription because through work, they found focus. I had the mother of an intern phone and thank me. Some military pilots who later get a job with the airlines discover they don’t need their ADHD prescription because the demands of the job are high enough that it keeps them focused.

How do you make the spider web pieces?

I take a photograph of a spider’s web, transpose and trace it; then we wood burn around the spider web, so the web is left out and we fill in the middle (negative space) areas. So everything but the web is burned. I’ll usually do the first one and then people on the team take over. It’s like a teaching hospital here. A lot of the kids have talents that I don’t have, like patience. In order to wood burn you have to practise on a panel to get it perfectly and it can take someone a couple of months to get it down. I have a whole stack of failed one-foot tiles. You don’t get to work on this unless I really trust you. And more than one person works on it. Vija Celmins is an inspiration, and Alighiero Boetti.

Tape Dispenser, 2012, mixed media, 4.75 x 9.25 x 3.25 inches. Photograph: Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy the artist and Baldwin Gallery, Aspen.

I’m also interested in the way that you are influenced by film. Why does Barry Lyndon haunt you?

There’s the violence, and it’s the story of a man whose sexual passions control his existence and he never overcomes the damage of his childhood. Also, it’s the only tragedy where the character’s demise, which is usually in the second half of the movie, is as interesting as his ascension. Usually, the second half isn’t as good and it falls apart, like in Scarface. There is the shoot-out but it’s kind of camp. In Barry Lyndon we see the breakdown. Kubrick is my favourite director and I think it’s his finest, most perfectly made movie. It’s an American scale European history painting.

You also have a piece that duplicates Colonel Kurtz’s final statement in Apocalypse Now, before he is executed.

Yes, it’s wood burned through a palladium leaf panel and from the side you can see all the panels. It includes the horror speech in its entirety. I am interested in fear and it is the fear that is always struggling against indulging in or trusting my intuition. I have to take chances and do things I don’t fully understand because an artist’s best work lies just beyond his understanding. I live for finding the place and the confidence to do that.

But when you start messing with death camps you had to know that something was going to hit the fan. Or were you naïve?

When I first made Chanel Guillotine I was really afraid that I was going to be sued by Chanel and I have to give a lot of credit to Thaddaeus Ropac, my dealer in Paris, who said, let me worry about that, I’ll take responsibility. You make your art. It gave me a lot of confidence. I wrote an essay about the controversy that was generated by some of my work. It is a true expression of where I came from and I’m proud of it. It’s about my childhood in Connecticut; it’s about Hebrew school and punk rock and not giving a shit about Hebrew school; it’s about getting cut from the soccer team—I had to choose between them, I missed practices because it was at the same time. But it was also about the rituals of consumerism. It’s all in there.

Do those pieces scare you in any way?

Well, the guillotine can cut your head off. They’re real things, like the electric chair. I think of course of Chris Burden and Marina Abramovic. What makes them mean something is that they are real. A lot of that comes from Burden’s work in that it was always a real thing. I didn’t even see it as art. It was something closer to Candid Camera or Mythbusters. Or even NASA because that’s not really science; it’s an expression of what we can do with science. Going to the moon is this unbelievably cool thing to do but you can’t get anything out of doing it. It doesn’t mean anything.

Bill Woodrow operates in a different way from you. His Hoover Breakdown is produced umbilically out of another object. You never went in the direction where one thing transforms into another?

The best part of my job is getting to be a student my whole life, so I get to study an Electrolux and make it from scratch. When I saw Woodrow’s piece, The Long Aspirator, 1979, I was living in London and I thought he was the most interesting artist at that time because he was really building stuff and then had the audacity of casting it in concrete. He chipped away archeology-style to reveal the relic. It looks like a giant snake but excavating it was really touching. I’ve never had the nerve to just put a urinal on a pedestal and call it art. I’ve always felt that I have to make the pedestal and make the thing. You know the line from the song, “you can’t take that away from me.” You just can’t remove those two thousand hours in that spider web. I mean, I can draw a spider web in a couple of hours but to put two thousand hours into it is different. My way of seeking out a way to a clearing has been through the ritual of work.

Did you know Tony Cragg when you were in London as well?

Of course. It was Cragg, Richard Wentworth, Richard Deacon, and at the same time there were all the Americans—Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Ashley Bickerton, Robert Gober, Peter Halley and Jon Kessler, whom I was very close with. It is funny to see where they all are now. Kessler was the artist whose work I related to because there was so much thrift shop junk and yet it was so sensitively managed.

You also admired Koons, whose Rabbit is one of the most perfect sculptures ever made.

Absolutely. That piece makes everything he has done since valid because it is such a breakthrough. It has to do with the sensuality of the form. It was as beautiful and as simple as Bird in Space.

The Brâncusi piece that has been so instrumental in your work is The Endless Column. You’ve done at least three iterations of it, including Endless NYNEX.

I think it is the only one I can legitimately make. I have thought about making Bird in Space because when you look up Brâncusi in the dictionary, that’s what should be there. Every time I look at it, I can’t see anything other than Warhol’s banana.

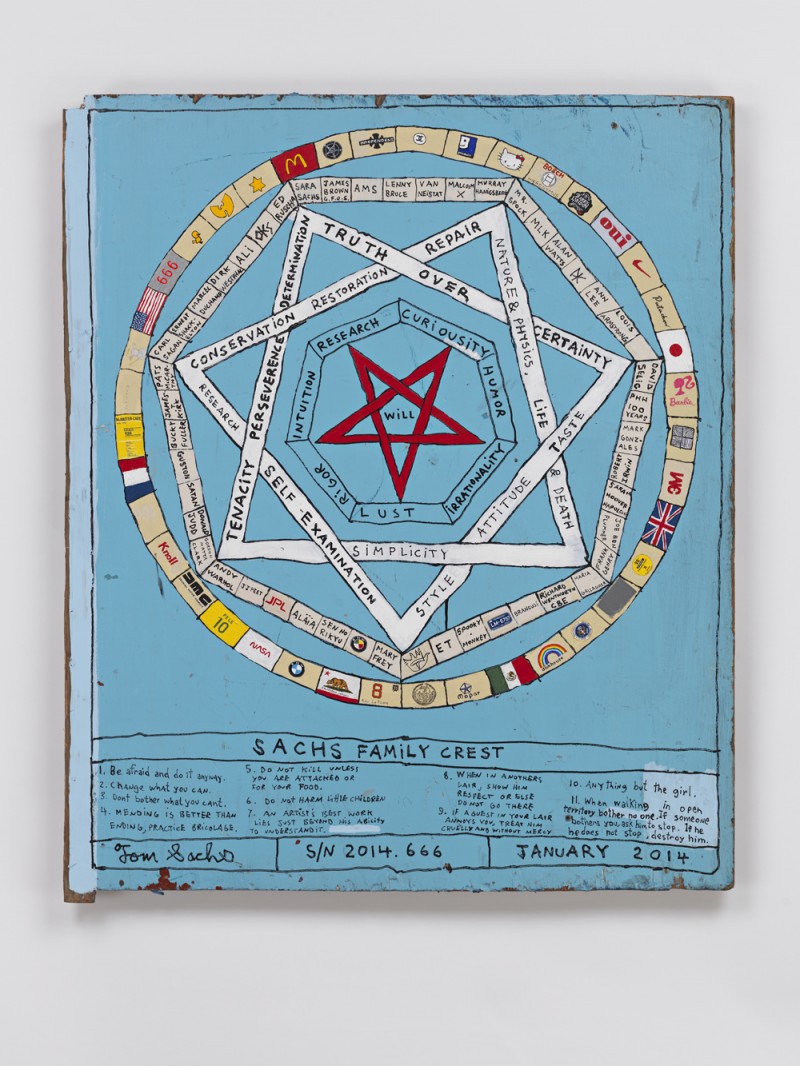

Sachs Family Crest, 2014, synthetic polymer paint, enamel, plywood, 41 x 34.5 x 0.5 inches. Photograph: Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris.

A Donald Judd minimalist inflection is evident in a lot of your work. That is also part of the vocabulary that you’re using.

I’m working on a Sachs family crest and Donald Judd is a big part of it. I have a specifically designed Donald Judd table that I made with resin and plywood. The specs are precise and the thickness is exact. He would never join it the way I did and it would never be filthy, but that’s my way. On top of it is an aerospace grade utility container, a milk crate for my space program. We all use milk crates for carrying books and records and things like that and I thought, let’s make one for NASA. One of my friends who works at Jet Propulsion Laboratory helped me with the structure path. I’m not going to say it is NASA-approved but it has been NASA-engineer vetted.

Is Untitled (Monolith), 2014, also NASA-engineered?

In a way. They are called lightening holes to lighten the structure. It’s a British term. You are always looking for straight diagonal lines. If you imagine a space frame structure then you pretty much have an even zigzag and everything else is unnecessary.Of course, it is super-decorative and I’m not going to discount that. If you look at the structure of rocket ships going back to Prouvé and American and British World War II airplanes, they are very beautiful. I call it art sculpture. Everything else is representative of something but this doesn’t really mean anything.

When I first saw pictures of Unite I thought of Judd and a certain kind of minimalism, and then when I saw all the stacking I thought of Nam June Paik. I figured you were just having fun inside the playground of contemporary art. Those weren’t your sources though?

Yes and no. I’m attracted to Le Corbusier’s building in Marseilles and to Donald Judd, and they’re related in that they are these stacked cells. There is a formal comparison between them. Now I love Nam June Paik’s stacked TVs but I also loved 42nd Street Times Square when you would walk by and see yourself on TV for the first time, or the evil villains on Superman who would have TVs stacked up so they could watch them all at once, and David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth, the super-genius who can watch five TV shows. I’m aware of these things but I’m not afraid to use them because Nam June Paik doesn’t own stacked TVs and I don’t either. It’s just like I don’t believe that Johns owns the flag. When people see my work they’re obviously going to think of Johns’s flag and they’ll think it’s a bargain to buy a Sachs flag compared to a Johns flag. But that’s just this super narrow band that is our little world. When I was at Barney’s I learned that my sculptures aren’t competing with Johns; they’re competing with a pair of Air Jordans. It’s the whole world. And you can’t worry about the critics; you’ve got to worry about the man on the street because he is the real thing.

But inside the territory where art comes out of other art, you’ve made very specific pieces, like the Mondrians. Whereas your abstract works like Red Sells and Ab Ex seem more generic. But your sourcing can be very particular. What determines how you use artists as points of departure?

I take different things from different sources to make things that represent me and those are made out of duct tape, a material that is an American birthright. Painting isn’t mine but duct tape is. When I left school I really loved Mondrian and I realized I was going to have to dedicate my entire existence to the world of money to get one. I knew right away that was a compromise I was not going to make with my life, So I went to the museum, studied one and made mine out of gaffer’s tape. I got to enjoy being a student and I realized I was probably spending more time with this particular painting than Eli Broad who paid many millions of dollars to buy his. So I was feeling pretty lucky because contrary to what I’ve said, I do love art. But then, of course, it is not a genuine Mondrian. Although I would say it is real. It’s not a forgery or a copy; it’s a model done in a different material, in the same way that you go down to Canal Street and buy a pair of Gucci sunglasses for five dollars. They’re real; they’re just not authorized. They say Gucci and they protect you from the sun, but instead of being made in Italy, they’re made in China. But when you leave them in a restaurant you’re not going to panic and run after them; you’ll just buy another pair for five bucks. There are some advantages to that. I wouldn’t rule out inauthenticity as a negative thing; there are a lot of possibilities there.

Unite, 2001, mixed media, 86 x 207 x 38 inches. Collection of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photograph: Tom Powel Imaging Inc. Courtesy the artist and Solomon R. Guggenheim, New York.

You describe art as a shelter because you get to do things you could never otherwise do. The other thing about art is its sense of play. In looking at your work, I often think you’re still a kid playing with models.

That is a supreme compliment. There are people out there who don’t take what I do seriously and to those people I say with the straightest face that they can go fuck themselves. I’m not doing this for them. I am doing it for me and for my community, but it has to be a satisfying experience for me. Making Unite, which was a gigantic project, was really fun. I got to go over there to Marseilles, I got to build it, the experience of which was like teaching a graduate school unit except instead of getting paid by a school, I had the privilege of employing my team. There are 20 people who know all about Unite and can speak about it and now my Le Corbusier library is deep. I’m bragging because I’m so happy that I was allowed to play. This is all because I was a remedial student. I was denied the pleasure of an academic experience up until college and I did ninth grade twice. As they would say in the Marine Corps, I wasn’t motivated. I was violent, I was getting into a lot of fights, I had a difficult childhood at home, my talents weren’t channelled or cultivated. Everything was hard and there was nothing I was successful at. So I had special tutors and psychiatrists. I think maybe if it had been today, they would have prescribed Adderall, which I think is an extremely dangerous drug that should only be used recreationally. I’m very successful here because I love what I do; that’s the only measure of success. And play is important because that’s where you’re failing and learning and experimenting. If I won the lottery I would continue to do exactly what I’m doing now.

Is getting to a place where you don’t know what you’re doing something you have to cultivate? Do you have to unlearn what you know to get to the nervous place?

I think that’s fair. It gets harder because I am an expert carpenter and welder and I’m pretty good at painting with acrylics. I know how to get it done using a projector or computers. I think that’s why I’m doing the ceramics. But now I’m learning about porcelain pretty quickly and it’s getting to be less interesting. I’m not afraid of materials, so the learning curve is dropping off. But what’s cool about ceramics is that it is a gigantic world of things that I get to master, like the firing and the glazes. I’m using porcelain clay and these are all pitch pots; I don’t use the wheel. And I don’t want to ruin something because I don’t know how to use the kiln, but my friends at the 92nd Street Y place my objects in a good part of the gas fired reduction kiln to get the best results. The first dozen were great and now I’m at 200 and they’re starting to get worse.

You seem to worry about radicality in the making and not in the content. Does the content never take you into risky terrain?

Generating content is easy. We live in this incredibly fucked up world; just turn on the TV and the content is everywhere.

Your content has been outrageous in many ways. A lot of the things you have made deal with things that people don’t want to see in art. Did you ever have any reservations about what you could do?

No, and I think there have been costs and that is mainly because when I grew up the art that influenced me was hard-core punk. The Dead Kennedys was the biggest and the best without a doubt and the most aggressive. Their name alone still offends people. I think they were amazing political activists who were commenting on the end of Camelot and this shit world that we had fallen into. In the case of The Sex Pistols, you don’t write a song like God Save the Queen because you hate England; you write it because you love England and you’re tired of seeing the old lady kicked around.

Would you say the same relationship exists between you and your use of Jewish history and culture in your work?

Yes. I have nothing against the Jews. I’m conflicted about Israel and any religious dogma is obsolete, so I don’t identify myself philosophically as Jewish. Culturally sure, but I think these are important things to be talking about because when it was taught to me it was taught in the most hideously dogmatic way. I couldn’t relate to it. It was the same thing as learning non-applied math or science and of course I’m skeptical because I’m a scientist, and science is my religion. Then there was no connection with spirituality, which through my art and appreciation of nature has become a focus. I don’t have a lot of fear about those things, but it has cost me because of the public’s offense to my subversion of guilt-driven religious dogma and the use of dark humour as a critique. I’m not trying to offend anybody, but sometimes you have to break a few eggs if you’re going to make an omelet. Lenny Bruce continues to be a cautionary tale and my hero.

What is your thinking behind Mr. President? It seems to enter into the world of conspiracy theories.

The gun is the Mannlicher-Carcano that was allegedly used to shoot Kennedy. I bought one and the logistics don’t make sense. No one with Oswald’s expertise would waste his time with this too-small-a-caliber rifle, so there has to be some missing information. But the other side is mixing conspiracy theory with Jack and Jackie and the sexiness of Marilyn’s birthday song. Confusing all those things makes for a richer storytelling experience. But I don’t really care who shot the president. The tragedy is that he was killed and it marked the end of Camelot. His lunar directive was honoured by two following administrations culminating in the 1969 triumph of the moon landing. King’s dream was realized in his martyrdom and the fight continues beyond this day where we now have a black president. But for me the real tragedy was when Malcolm X was assassinated because he hadn’t done the work he was on his way to doing. He had made this incredible personal transformation but he hadn’t taken it to the street. His first couple of transformations from street hustler to religious leader empowered a lot of people, but once he started to take apart the structure of the nation of Islam they killed him for it. He wasn’t just uncovering a corrupt religious sect; he was uncovering the truth that it is not about race, that there are blond-haired, blue-eyed Muslims, which is what he discovers in Mecca, and that they are his brothers. The logical next step is that we are all brothers and sisters, whether you worship Jesus or Allah. He was killed for those sentiments because of the emotional challenges they posed.

Do you think of your art as being instrumental? Is it your intention to change the perception of people?

I think art can have a huge effect. Art through punk rock saved me. The Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat and Bad Brains are bands that saved my life when I was at a low point; they helped me see another way of looking at the world. Obviously, it is the thing that I have dedicated my life to. I know that my art communicates to people; it might just be the people in my community, but conversations like this help us look at the world in a different way. Besides having a good time, it is almost a responsibility to keep doing it.

You do a lot of drawing that says what it is you are going to do. Is that a methodology or is it art? Where does it fit into your practice?

To me the drawing is the only real thing. It’s where I work out the dimensions, proportions, the feeling and the ideas. I’ve got drawings of things I will never build, like stupid ideas where maybe only one little corner is really great and that’s the idea on which we’ll expand. I have the drawing for Unite and basically I thought that whole gigantic project up in about 10 seconds. But it took years to realize and refine it. I was on a sleep-deprived high from a red-eye flight and I went to my hotel and I couldn’t sleep. I had made a model of Villa Savoye, which is my favourite, but Unite is his most important project and I made a little drawing of it. I was thinking what would be the next step. I had bought this remote control car and I thought, what if I make it to that scale because most of his important buildings had a relationship to the automobile. Then I started combining it with a race track and security guards to keep people away from the cars, and the project grew from that. But the drawing was where I started to make the comparison between Macdonald’s and Le Corbusier as successes and failures of Modernism.

Is that notion of hybridizing one we take for granted, the idea of combining things and mixing scales? McBusier is a classic example.

It’s probably my main formula: one + one = a million and finding the third thing that connects the two unlikely things. That’s the secret. I think in the ’80s people were throwing around the word “pastiche” to talk about Postmodernism and that conversation is still really alive in me. Chris Rock said that your best “forever” music is the music you were listening to when you were first getting it on. For me it was Public Enemy sampling James Brown and a car alarm. That was the kind of art I loved; that was Rauschenberg’s collaging.

So dub is a methodology you couldn’t escape?

That defines it. Lee Perry listening to the radio and then going to the studio and recording those Al Green songs from memory, which came out a little bit differently because he’s a genius and he made his version better. That dovetails into model-making. Models are versions and they are better because they are unauthorized; they’re more elaborate; they are done with more care. Or they’re done out of the wrong material, which makes them mean something. A duct tape Mondrian means a lot more to me than an oil-painted Mondrian. If it falls apart, just put more tape on it.

You seem never to run out of ideas. Do you have more ideas than you’re able to realize?

Yes and that’s why I employ 10 people, because I have a sense of urgency and I want to realize all these ideas. Death approaches.

McEndless Column, 2001, mixed media, 128.5 x 11 x 11 inches. Photograph: Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

I am interested in the ambiguities of your understanding of value and how you view things. You buy a Rolex and you paint it black, so in one way you get away from the trademark, but then because your version is editioned it becomes even more valuable.

I think the Rolex watch is an idiotic thing because what you are buying is the associated value of Jacques Cousteau, James Bond, Edmund Hillary— whoever had that model watch. If we believe that Timex line that “it takes a licking and keeps on ticking,” then we are succumbing to advertising. But at the same time it’s a status symbol and I love the idea that it’s a good watch. So I want it but at the same time I’m annoyed by it. My way of dealing with that contradiction is to transform it by painting it.

You had no reservations about making Giftgas Giftset, in which the gas refers to Zyklon B, the kind used in the death camps? I was raised Catholic and were I an artist, I don’t think I could make that piece. I guess I am asking whether you have more permission to do it?

I like that question but I don’t like the answer. People say I have permission to do it because I’m Jewish and you don’t because you’re Catholic, but I think that’s fear talking. That’s why I felt like I could do Barbie Slave Ship. If you don’t think about the issue then you’re struck in the face by it. It’s hard for a German to make a Jewish joke and it’s hard for a Jew to make a black joke. Somehow Sarah Silverman tells us it’s okay for anyone to make an Asian joke. I don’t know why that is but she’s unapologetic about it. I’ve learned a lot from comedy. Comedians have all these tricks, like Silverman uses self-effacement, a strategy that makes you trust her. I admit I was a little afraid when it came to the Zyklon B canisters, but I had the confidence to do it because when I went to Hebrew school it was basically Holocaust school. I hated it but if I could get the teacher telling Holocaust stories it was at least fun and gory and interesting. What 12 year old isn’t going to do his hardest to distract the teacher to get him to talk about anything other than schoolwork? As a result, I learned all about the Holocaust_ and while I’m not an expert, I certainly know more about it than the Hebrew alphabet. The more details you learn, the firmer the ground you stand on. When I did Barbie Slave Ship_ I read everything I could about the slave trade and before that about the Homogenocene in Europe and the Americas, about what it meant and how things have changed.

Is a piece like HG (Hermes Hand Grenade) in a different category of content than Giftgas Giftset?

They do similar things; they take something we recognize and they use humour to confuse our read of what we thought we knew about the object. But I would never do the Hermes Hand Grenade now because I don’t think it tells my story as much as other objects do, although it’s a well-made, seductive object. Made in 1995, HG, which stands in as both the atomic symbol for mercury and the name of the god Hermes in mythology, is a kind of rebus. And I love stuff that blows up, and like everyone else I have made fireworks. So I was trying to combine all that in a single object. The grenade was a way of studying this super destructive, negative, anti-personnel thing.

You like elaborate details that bring additional meaning to the piece. A viewer wouldn’t necessarily pick up on the connection between the periodic table and a god in Greek mythology. Those are narrative threads that may not be evidently readable in the piece.

Anyone who studied the liberal arts and some science could put it together, but what I’m banking on is that even if they don’t, they’re going to appreciate the craft, the way the thing is made and its general appearance. Maybe someone who isn’t into fashion doesn’t know what Hermes means. It’s just the combination of an expensive thing that they want with a violent thing they fear. I think it was a fair piece for that time because I was working at Barneys doing window display and I was coveting Hermes leather. I don’t own a single Hermes thing but my wife does and they are very nice. So that piece was then. But it’s not so different from the Plywood Barbie. It’s a very simple thing to make a Barbie out of plywood. I could have done it better but doing it to the level I did with a wing nut on the hip is something I’m very proud of.

Germano Celant mentions the word obsession in his interview with you and you deny that you are obsessive. You don’t think you’re obsessive?

I am but I guess I’m embarrassed by that. I spoke earlier about giving in to the advertising world and wanting a Rolex because Cousteau had one and I admire him and his work. So at the same time I’m admitting I’m a sucker for wanting it, I also lust after it. I see the folly of that and that’s why self-examination and research are part of the same thing for me. As a complicit participant, I am particularly authorized to discuss consumer culture.

For someone who was raised so thoroughly American, you look towards England in a lot of your thinking.

Yes. There is the Arts and Crafts movement and William Morris. If I was a better student I might be more into France, but I get by in England. I also feel that as Americans we are really English (or super England). The Industrial Revolution happened in England but all that stuff came to its supreme representation here in New England. I have a huge connection to England in the way that things are still made there. If I could have any car it would be a Morgan. I don’t like the way it looks but I like the way it’s made. They still make the leather strap to hold the bonnet down. It’s totally bespoke but it’s a dumb car with no roof, so I would never get one. I certainly would not get an Aston Martin because that’s like getting a BMW or a Mercedes. They’re generic, they’re like every other mass produced thing. It’s not about how it’s made. I favour Norman Foster or the Brompton bicycle, which is my bike. I can’t explain it, but that same melancholic nature that happened in England happened here in the North-East Industrial Corridor, and in all of industrial America. I got to experience that decline in my lifetime, whereas in England it was before my time. Punk was the art that followed the English decline. Now in the USA we have Kanye and Kim.

It’s historic rather than nostalgic?

Yes. It’s in the immediate past. In the studio I have cabinets from the machinery district that I pulled out of a dumpster. And there are other cabinets where my grandparents, who were doctors, kept their patients’ files. And the Putnam Rolling Ladder Company was just down the street until a couple of years ago, and I pulled a ladder I’m using out of a dumpster as well. It’s a pain-in-the-neck but it works.

Don’t you get accused of being too ballsy, to use your own word?

Yes. People even think I’m racist and not rigorous and misogynist, which to me seems insane. I’m just not afraid to take on those issues. I know you’re not supposed to talk about those things, but art is an occupation where you do the things you’re not supposed to do. As Marcel Duchamp said, art is either plagiarism or revolution. ❚