The Bochnerian Not

An interview with Mel Bochner

I can’t begin this introduction to our interview with Mel Bochner by saying, “What interests me about his work is …” because everything about his work interests me. What I’ll address in particular, however, is, for me, the Gordian knot, the conundrum of his repeated assertion that “Language is not transparent.” The statement appeared first as a four-part work in 1969, bearing that phrase as its title. A rubber stamp on four notecards, saying once, “Language is Not Transparent,” twice, overlapping on the second card, then three times, I think, the phrase laid down over itself; and then on the fourth card, a multiple stamping, an obliteration of the phrase, not cancelling out but making manifest by way of demonstration, stamped into illegibility on itself. The next iteration of the phrase, in 1970, as though white chalk on a black board, was a wall painting, a statement of a certain kind of independence in its apparently unruly drips running to the floor—a painting but not a commodifiable object—a work that Mel Bochner has done in numerous locations, each one unlike the one before.

Left to right: Mel Bochner, Cezanne Said, 2015, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches; Drool, 2015, oil and acrylic on canvas, 91 x 60 inches; $#!+ $#!+ $#!+, 2016, oil on canvas, 60 x 45 inches. Images courtesy the artist.

Language is not transparent; that much is clear. We know about its ambiguities, the freight of culture, its failure to be the full parallel or replica or equivalent of the thing it addresses. After he had completed art school, Mel Bochner went back to university to read philosophy. In the thorough catalogue essay for the exhibition “Mel Bochner: Strong Language,” mounted at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2014, Norman L Kleeblatt noted that Wittgenstein’s writings were influential for many artists in the ’60s and ’70s, Bochner among them. In particular, Kleeblatt said, it was because of Wittgenstein’s reluctance to close off on anything, and, he wrote, that the philosopher “urged an incessant questioning of ideas and assumptions,” ideas well-evidenced in Bochner’s work.

So the conundrum: If language isn’t transparent, how do we see through to meaning? Well, we can’t—it’s not possible to read with any certainty. In his interview with John Coplans published in Art Forum in June 1974, Bochner said he felt drawn to Wittgenstein’s beautifully concise summation: “What can’t be said must be passed over in silence.” Speaking with Coplans about looking closely at the work of Kasimir Malevich, Bochner continues, “If you have had any deep experience through your own eyes it gives you a type of knowledge that’s not transposable to any other knowledge. There is an order of thought which is only visible.” And further, on standing in front of a work of art, in this case by Malevich, “Malevich brings us to the edge of language” (Solar Systems & Rest Rooms, Writings and Interviews, 1965–2007, Mel Bochner, An OCTOBER Book, The MIT Press, 2008). More is said in this exchange; I’ve selected lines that seem to address my puzzling through the opacity that “not transparent” could mean. No one speaks better on Bochner than Bochner, and Malevich appears the perfect medium to carry the question of the mutable gap between language and paintings, or text and colour.

Obsolete, 2016, oil on canvas, 88 x 80 inches.

About painting, and leaving behind his engagement with Conceptual Art, of which he was named one of the primary instigators, Bochner explains why, in 1979, he began to make paintings. He tells us in the following interview that this wasn’t the beginning, that he’d always been a painter, just one who didn’t paint. What he introduces is the satisfying idea of “surplus” to explain the difference between Conceptual Art and painting on canvas. It’s a nice word of plenitude, a round word of abundance—enough and then some more—for later. And later is the issue. It’s what remains in the eye, in the being, after the idea has been seen and understood. It’s what he identified in his conversation with curator Johanna Burton in the catalogue Mel Bochner: Language 1966–2006, published by the Art Institute of Chicago, 2007, as “a surplus meaning, a visual meaning … that survives the consumption of the narrative.”

If language is not transparent, what happens when colour is added to it? Is the eye confounded in the oscillating flicker between colour and text, and is colour really more legible than language? Bochner’s series “If the Color Changes,” which he began in 1997, challenges the viewer to settle the eye and see. With work, it can be done but only when you peel the layer of one element from the other; it’s either colour or it’s text but it can’t be both together. But it is a painting, right? So, what’s it about? What’s its subject, the increasingly agitated viewer asks. That’s the subject. The question is its own answer. All the issues/ideas/queries the artist raises in the series “If the Color Changes” and with the “Thesaurus Paintings” that follow are here. His dichotomies, prevarications, ambiguities, screens and covers, assaults and cajoling, the chromatic treats and rewards, the shocks and surprises, the anomalies. Certainty slips away, and the apprehension that can’t be articulated is in the gap between language and colour, between meaning and sensing or feeling. That’s the place art exists, the artist tells us, “in the space where the mental and the physical overlap.”

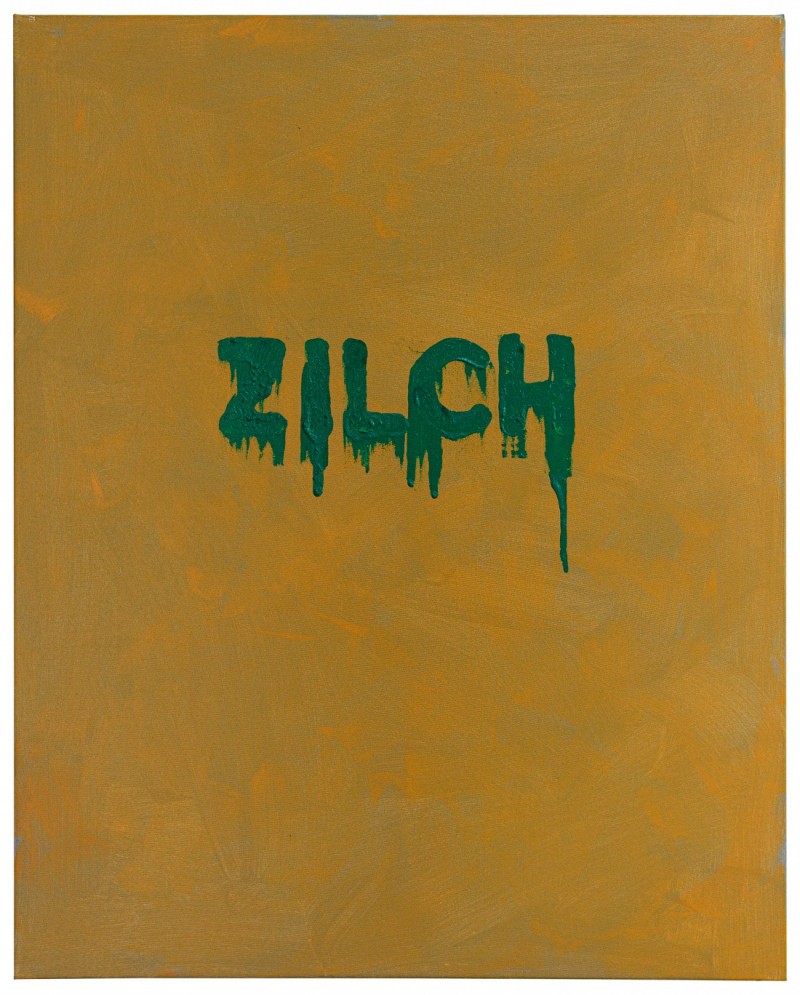

As for anomalies, I nominate Mel Bochner’s painting Zilch, 2016. Clearly readable, it’s a metonymy, standing in for itself, and, contrarian that the artist is, Zilch is really something! The green painted word sits on its canvas ground proud as a fluffed winter chickadee. There it is, everything and nothing, at once. Really, the last word on nothing, with its unlikeable palette. And perfect, the word’s meaning undercutting its presence, and language still is not transparent.

I want to talk about beauty, a word I don’t think I’ve seen associated with Bochner’s work. It’s my word, not his, but intentionality is his and it is certainly evidenced in the work; the choice of words and colour is not happenstance. When palette undercuts image, an ellipsis presents itself to me in a painting like Howl, 2016, where the title alone conjures the poet Allen Ginsberg, but the language—Snort, Holler, Hiss, Bark, Snarl—has no direct connection to the long poem of the same name, or to the painting’s minty, surfy, ocean-foamy shades of green. But it’s beautiful. As are: Obsolete, Block Head, Blah, Blah, Blah, all from 2016. Here, it seems Bochner is testing his assertion that language is not transparent because, with these paintings, the language does step aside and makes way for a hossana of pigment and gesture on canvas. The words and letters are overridden, and what slips to the fore of perception is pure ocular pleasure, maybe something akin to James Elkins’s alchemical delight.

Language Is Not Transparent, 1969, rubber stamp on notecard, 5 x 8 inches each.

Much of the vocabulary Bochner uses falls short of being words of endearment or praise or celebration, but The Joys of Yiddish, in various iterations, or Jew are a different order. Norman Kleeblatt noted in the catalogue Strong Language that Mel Bochner had told him his use of language was deeply rooted in Jewish thought, with its essential emphasis on reading and interpretation. The tradition of iconoclasm is also his with the Second Commandment’s injunction against the making and displaying of graven images. And he is an iconoclast in the sense of the term’s other meaning—challenging received notions, with some consistency.

There is a hugely satisfying irony in the placement of The Joys of Yiddish, 2013, mounted in Munich in a highly visible horizontal band running the full length of the facade of the Haus der Kunst, an edifice built by Hitler to house examples of art considered ideal to the Nazi sensibility. The gratification of this placement is measured against the painting Jew, 2008. Bochner found a racist litany on an anti-Semitic website where there was ample vocabulary with which to work. The painting is disturbing to read, difficult to look at; the harsh acidic yellow against a terminal grey ground presents with increasing urgency and more agitation as the words build to the bottom of the canvas. The underpainting and the surface drips seem an attempt to feint and elude the ferocity of the epithets being hurled and received. Speaking about this work in a 2007 lecture delivered at the New York Institute of Fine Arts, Bochner said, “All abuses of power begin with the abuse of language,” echoing the words of philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel, who wrote, “It is from the inner life of man and from the articulation of evil thoughts that evil actions take their rise. Speech has power and few men realize that words do not fade. What starts out as a sound ends in a deed” (“What We Might Do Together,” Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity, Essays, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1996).

Mel Bochner told us he sets aside certain ideas, bracketing them to be revisited later. Ideas held early on are brought into the present for reconsideration and to be used anew. Nothing is lost or left behind. A satisfying word picture in my mind is a green and gently rolling meadow. A pacific cluster of sheep moves nicely on. A Border Collie is focused on the task: rounding up, trotting ahead, circling back, moving his charges inexorably forward. Not a straight line.

This interview was conducted with the artist in his New York studio, November 7, 2018.

Border Crossings: You have said in another interview that you always thought of yourself as a painter, just not as a painter who painted. Do you have a different conception of yourself now? You seem to have become a painter who actually does paint.

MEL BOCHNER: Yes, I always thought of myself as a painter who just didn’t happen to paint. Now I think of myself as a painter who happens to paint. But at the same time my earlier work continues. For example, that study on the wall is the sketch for a Measurement installation at Dia Beacon, based on an idea from 1969.

Is it your sense that nothing ever gets lost; things are always reiterated or reclaimed?

I like the idea of reclaimed. I don’t think ideas have a shelf life. My job is to continuously try to move forward and let things go where they’re going to go. At certain points an idea feels like you’ve exhausted it, but at another point in your life you realize you didn’t take it far enough. The word portraits of Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt and Robert Smithson sat in the drawer for 30 years until Richard Field was organizing my show at Yale. He came across them and said, “We have to show these.” When I looked at them again I had the feeling that there was still juice left in the lemon, that I hadn’t squeezed it all out. But, at that point, I didn’t know what to do with the idea. It couldn’t be portraits again. I had done that. So a couple of years later I came across the new edition of the thesaurus, which was totally different from the one I’d had in college. It had obscenities in it, which struck me as being a dramatic change in the politics of ordinary language, because little kids use a thesaurus and now it says “Fuck you.” So I started exploring what had happened to the boundaries of public discourse, fishing around in the thesaurus and seeing what I could catch, picking out words that interested me, or that led somewhere, or that I could arrange into a narrative. Going back to the thesaurus was not a return to something from 1966. Then I had chosen a word in advance for Eva; I had chosen one for Sol and one for Smithson. Now I was looking for ways in which the synonyms could create a narrative. It felt like the idea was fresh again.

There seems to be a progression in the Thesaurus paintings. They often start in a positive frame of mind and then the tone of the words begins to shift, so by the time you get to the end of the painting, they’ve become dark and scatological. Is that a personal inclination or simply a reflection of the way the words are listed in the thesaurus?

The thesaurus lists words objectively by parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives. The “dark and scatological” is the intentionality of the paintings. The words are like a fund that I can do whatever I want with. In the earlier ones I would start with a more Latinate and formal language and then let it all collapse. That’s my “personal inclination.”

Zilch, 2016, oil and acrylic on canvas, 30 x 24 inches.

That it’s entropic?

Basically you could call it entropic. It self-degrades.

So let’s talk about your early interest in language. When you read Wittgenstein, does he touch something in your sensibility with which you could begin to work?

I don’t think there is any direct causal relationship between Wittgenstein and my work, other than what you might call a certain affinity for a way of thinking. What I was looking for in my early work was something that didn’t belong to anyone else. It occurred to me that two things didn’t belong to anybody, because they belonged to everybody: numbers and language. Whatever you did with them, anyone else could have done. So they didn’t have any direct art priority. I was very taken by the Jasper Johns show in 1964, the surprising and mysterious ways that he introduced language into the visual field. And, of course, by his number paintings. But in a Bloomian sense, it seemed to me he hadn’t taken it far enough.

So you had to carry the narrative further?

Well, when you’re young you’re looking for a spot where you can build your own sand castle.

…to continue reading the interview with Mel Bochner, order a copy of Issue #149 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!