Dan Graham: Mirror Complexities

“I like to get into new areas,” Dan Graham says in the following interview, “and I like them to be in a borderline situation, rather than definitively one thing.” For over 50 years, Graham has located himself in a number of borderline situations, and from that position of in-betweenness has made an art of perplexing simplicity. Critics generally assign his Schema, 1966, a series of instructional sheets that gave editors sets of data for the composition of printed pages, a generative place in the history of conceptual art. But the various Schema were themselves in border zones of their own, part poetry, part criticism, part visual art. Their newness was in their indeterminacy.

Similarly, the deliberately uninflected and abstract photographs he took in 1966 of tract houses, storage tanks, warehouses, motels, trucks and restaurants, subjects he passed in the train on his way into New York from the suburbs, occupied two zones in his mind. In his own estimation, he was “trying to make Donald Judds in photographs.” His first pavilions, beginning with Public Space/Two Audiences made for the Venice Biennale in 1976, were a cross between architecture and sculpture. His cross-disciplinary mobility functioned in all directions: Sol LeWitt’s early sculptures encouraged Graham’s interest in urbanism because the sculptures seemed to him to be about city grids.

Public Space/Two Audiences, 1976. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

It’s because of this overall sense of one category of art drifting into another that Graham says, “all my work is a hybrid.” His idea of hybridity was predicated upon an intense degree of experiential involvement; in performance/video works like Nude Two Consciousness Projection(s), 1975, and Intention Intentionality Sequence, 1972, the audience was part of the performance; just as audience involvement was also critical in a number of the pavilions. In Public Space/Two Audiences, we watch ourselves; we watch others; we watch others being watched; and we watch ourselves being watched. Graham found the ideal material to make this kind of awareness inescapable: glass and mirrors that are variously transparent or reflective force audience members into a participatory role.

In a Graham pavilion, you are all eyes. Sometimes you see a reflected image; at other times the ghosted form of a figure through transparent glass; at other times the shadow of your own figure. This process of shifting apprehension is one way of measuring the loss and rediscovery of self and other that is central to the experiential impact of Graham’s pavilions, whether they are inside a gallery or outside in a garden or a sculpture park. You are involved, willy-nilly, in an architecture of self-consciousness.

Another effect of this kind of layered, intense looking is a sense of disorientation, a combination of informational overload and physical vertigo. Even in an early video work like Body Press, 1970-72, there are moments in the mapping of the body where the man and the woman merge and you can’t distinguish one from the other. This state of perceptual fluidity could have a phenomenological base or it could be drug induccd. Graham’s interest in rock music and the punk scene, an involvement that culminated in his remarkable film Rock My Religion, 1982-84, was as much a commitment to a way of life as it was a way of making an artful film. Graham admits that, as a loner, there was something in the group dynamic of the rock band that was especially appealing. He may have regarded his fascination as anthropological, but he was one of those anthropologists whose presence didn’t simply observe the phenomenon but altered it as well. There is invariably a double hook in Graham’s work. His pavilions always have two-way mirrors, which are simultaneously transparent and reflective. So they are about looking and being looked at, about accessing information and being information. In this way, his interest in intersubjectivity and the spectator crosses back on itself to become an aspect of self-interest, an awareness that carries with it no pejorative associations.

Dan Graham’s influence on contemporary art has been enormous, but in many of the published conversations and interviews with him, including this one, a sense of disappointment emerges about the level of recognition he has achieved. He sees himself as a “provocateur” and “a rebel”–these are his own words–and he is aware of the difficulties of sustaining this outsider position. He has been particularly concerned that his rooftop urban-park pavilion for the Dia Art Foundation in New York had been put in storage, a victim, as he sees it, of the institutional elitism that his piece was actually critical of. As it turns out, Two-Way Mirror Cylinder Inside Cube and a Video Salon, 1981-91, is being re-installed on the rooftop of the new Dia building in Chelsea, a development that has just been announced. Graham has said elsewhere that ” … the art object is what it is later in history, not at the moment it was first conceived.” The exhilarating news about the re-installation of the Dia piece is that it will have an opportunity to become itself again, in a new place, and in a new time.

This interview with Dan Graham was conducted in his New York studio by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh on Saturday, October 3, 2009.

Interview

BORDER CROSSINGS: I want to start with the magazine, a form that played an instrumental role in your early work. How do you regard magazines today as vehicles for either the production or the dissemination of art?

DAN GRAHAM: To be honest, I barely read them because I think they don’t have enough artist writers. There are some great artist writers, like John Miller, Mike Kelly and my friend, Nicolás Guagnini, who is an Argentinian Jew. I think that Modern Painters, as bad as it is, sometimes has good writing. But it’s very important that artists write about other artists and there isn’t enough of that anymore.

What was the attraction that magazines had for you in the beginning of your art making?

It was accidental. I did these colour photographs of New Jersey suburbs, and I was in a show called “Projected Art” in the contemporary wing of Finch College. The Assistant Editor of Arts Magazine, a filmmaker, was dating Mel Bochner, who is a friend of mine, and when Mel took her to see “Projected Art,” she said, “Why not reproduce these photographs in the magazine?” I wanted to do a fake think piece. Also, Donald Judd had written an article for Arts Magazine about the plan of Kansas City, where he was from, and I wanted to reference my photographs of New Jersey with Minimal art, which was just beginning. I also wanted to reference them to the real situation in suburbia. So I went to the library and researched tract homes and contacted a tract home developer in Florida who gave me a brochure saying, “Maybe you could squeeze something out of this.” I wanted to have a very long photojournalistic article, this fake think piece. But it was a sleazy magazine, and in the end they took out all my photos and just ran the article. I was also very interested in Jean-Luc Godard at the time. I thought his films, like Two or Three Things I Know About Her and A Married Woman, were a little like magazine pieces. I was especially interested in that kind of Pop culture. Much of my attraction to magazines was because they were disposable. What I wanted when I did Schema, 1966, was something that could be almost free, relating to each different issue, and disposable.

Warehouse in Neo-Colonial Style, Westfield, NJ, 1970. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Wasn’t the first presentation of Homes for America in the form of a slide presentation?

Yes. I liked the fact that with slides you get a certain kind of light quality. It was before backlit Cibachromes, but I was going for the same thing.

In seeing the slide format at the Whitney, I was struck by the photograph of a woman in a bus sitting inside a circular window. It reminded my of a similar photograph in Robert Frank’s The Americans.

The photograph was taken in Portugal. It’s a normal European tour bus. Peggy Gale was organizing shows for me everywhere in the world. I did a video show in Barcelona, and then she took me to Portugal only a few days after the revolution. You know, Homes for America, 1966–67, was this generic title which wasn’t mine. It was picked by the editors at Arts Magazine. But let me tell you something else about the influence magazines had on me. When I had my gallery we sold nothing. Dan Flavin was in a group show, and he said his fluorescent lights should go back to the hardware store when the exhibition was over. Sol LeWitt, whom I gave a one-man show to, said he wanted his work to be used for firewood afterwards, and Carl Andre’s bricks were supposed to go back to the store where he bought them. My thinking was that I could do something disposable with magazines.

Lichtenstein was after the same thing. He thought what he was doing with painting was to devalue it, but in fact, the opposite happened.

Lichtenstein was a huge influence on me because of ironic Jewish humour. Sol LeWitt’s early work was also very funny. He said his early works were jungle gyms for his cats.

You talked about your early minimal work as being anarchistic humour. Was that what you were after?

I don’t think I did Minimal art. I was influenced by Pop and Minimal art at the same time, and what I got into was intersubjectivity. In other words, the spectator became very important. I was very influenced by seeing Bruce Nauman, whom I had written about in “Subject Matter.” So I got involved with the performer I thought ought to be the spectator in their own perceptual process. One of the reasons this happened was when I was 14 I read parts of Being and Nothingness by Sartre. The mirror stage comes from Sartre’s idea that the child has an idea of itself in terms of ego.

So the mirror wasn’t just perceptual for you, it was also philosophical?

Two Adjacent Pavilions, 1978–82, is like a philosophical model because there are two egos looking at one another. Also, Rock My Religion, 1982–84, is anthropological. When my parents were in college they bought Margaret Mead, who was very influential and important in ’40s America. She wanted to teach sex education in primary school. I was reading her at 14, as many boys my age were, to find out about sex. So when Benjamin Buchloh says my work is sociological, I think it’s more about anthropology. It’s about the artist’s community and giving a sense of that community.

Was your home life the sort where you would have been encouraged to read Sartre as a teenager?

My father was a scientist, my mother was an educational psychologist, and they were both Jewish. My father was also very abusive to me, and I had a psychotic breakdown when I was 13. As a result, I didn’t do well at school, but I read difficult books, including Sartre. I was also reading Nausea and the Evergreen Review, which translated all the French New Novelists, and later on I read Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations. I mostly found these people on my own. I was a dropout, and the people I met when I had my gallery were either self-educated or over-educated. Flavin didn’t go very far and was almost a priest; Smithson actually dropped out of high school; whereas LeWitt was in the Korean War and studied architecture. The G I Bill allowed people to continue in school, so some of my artist friends were slackers because they stayed in college for a long time, and then other people I met actually never went to college.

What was the reason behind starting the John Daniels Gallery in the first place?

It was an accident. I didn’t have a job, and it was a vanity gallery for two friends of mine who wanted to social climb. Also my parents put in a bit of money, which allowed them to claim a tax loss. I’d read about the art world in Esquire magazine, but I didn’t really know anything about art. We sold nothing. It was also the year that Richard Bellamy’s Green Gallery went out of business. They were selling some things to Philip Johnson because David Whitney, who worked there, was Philip’s boyfriend. But I think it was too early for things to be successful.

I gather you didn’t know anything about running a gallery either?

No. Our first exhibition was at Christmas and anybody who wanted to be in it was included. The person who fascinated me the most was Sol LeWitt because we both loved Michel Butor. By the way, Homes for America was very influenced by Butor, who wrote a book called Passing Time, which is about getting lost in a Northern English city and finding the city to be a labyrinth. I was extremely interested in the idea of the city plan as a basis for art, and Homes for America was against the white cube idea.

You have said that LeWitt was the person who introduced you to urbanism.

Yes, but it was Michel Butor through Sol. Sol also worked for I M Pei for a period, so he was referencing the New York City grid. He also said he was very influenced by de Chirico, who based his work on Turino.

Were you using the gallery as a way of consciously expanding the idea of what art could be?

In one way, I was a student of what was in the gallery, and I learned a lot from it. I guess I thought there was a possibility to write and do art at the same time. Basically I wanted to be a writer, and what attracted me in art is that the people I admired, like Smithson, Flavin and Judd, were artist-writers. I liked the fact that art could be open to anything and, of course, Andy Warhol picked up on that. In the ’60s we thought that art could be an umbrella for many different things at the same time, and that was a very important idea for me.

So art was an expansive field, and language and the act of writing played a significant role in that field?

Exactly.

At one point you described yourself as a journalist.

I said photojournalist and I was making a joke. I wasn’t serious, but what I liked was the discipline that came with the framework of magazines. A lot of my articles weren’t published until much later, like the Dean Martin piece. “Eisenhower and the Hippies” was in page proofs when it was turned down. The same thing happened to Schema, which Arts Magazine pulled at the page-proof stage.

Cafe Bravo for Kunst-Werke, Berlin, 1998. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Schema is fascinating because it takes the substance of what writing would be, calibrates it and gives us all the component parts. In a sense it becomes structural.

It was a little like Borges and his “Library of Babel.” I also like the fact that it was disposable. At the time, Frank Stella was making paintings that were self-referential, but my idea of self-reference was very different. It had to do with using the magazine page to get rid of the idea of value. The work I was doing with magazine pages was actually two years before official Conceptual Art. Then Kosuth, who went to the School of Visual Arts where they taught him how to do advertising, simplified the idea of self-reference. Robert Mangold, who was Kosuth’s teacher, had mentioned my early magazine pieces, and Kosuth would show up on my doorstep and follow me around. He followed me to On Kawara’s and I couldn’t get rid of him. I think he actually took a lot of ideas.

I’m interested in hearing you talk about the influence ideas from literature had on you. Clearly reading has been a significant part of your practice.

I think you shouldn’t underestimate science fiction. That’s how I became involved in time paradoxes. I was reading Radical Software, which was very popular in New York, and that’s where I found out about Gregory Bateson and about the writing of Paul Ryan. So then I read Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind. I had multiple sources and a lot of them were not art sources because I didn’t come from an art background. So I was extrapolating into art from different readings. I didn’t think of myself as an artist until much later. I saw myself as a writer. It was John Gibson who asked me to write an article about work dealing with ecology. He thought I could be an artist and supported me as one, but I really didn’t have a sense of myself as an artist.

Do you think of yourself as an artist now after 50 years of making things?

I still see myself as an artist-writer. I write for pleasure. I do a column for Abitare, the Italian architecture magazine, and I just finished a catalogue essay on Sol LeWitt’s humour.

What made you make the shift to work in film?

I was interested in Nauman’s work, but I had no money for film or video. Then David Askevold at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design invited me to participate in his course called “Projects,” where conceptual artists would suggest work that could be done by students. Because I never went to college, the idea of teaching and being an artist in a Canadian art school was very appealing. They had film and video equipment as well, and my early work in video was related to the idea that video with a Portapak and feedback loops could be used for a learning process. So I did Two Consciousness Projection(s), 1972, with the students in Halifax. Lax/Relax, 1969, was actually first performed in a small gallery run by Charlotte Townsend.

The iteration in the piece is interesting. You talk about the Shakers using repeated phrases from the Bible to get into a kind of trance. Lax/Relax becomes almost trance-like.

I’ll tell you what it comes from. In the ’60s in LA every two or three weeks there was a new self-help situation, like Primal Scream. Today women do yoga, but back then, everybody was trying to get away from their problems through their bodies, and they would have relaxation exercises. When I was writing this article about Dean Martin’s TV show, I realized something very interesting: relax is very positive in American culture, but if you have too much lassitude, the way Dean Martin did because he was an Italian lush, then that’s negative. So I was putting together relax and lax. In a certain way, it was about Puritanism. And the breathing has a lot to do with Steve Reich’s phasing, and a little bit to do with men and women in bed together trying to have the same rhythm. But basically it’s a parody of what was New Age in Los Angeles in the ’60s.

Homes for America had a parodic dimension when you made it. Do you sense that the parody is as prominent now as it was then?

There were articles in Esquire magazine where sociologists were decrying the sterility of suburbia that were accompanied by very good photographs. I was imitating that in a kind of parody. But it was also a pastorale. As an upper-middle-class Jewish person, I was fascinated by petit-bourgeois, Italian-American New Jersey culture. So I could be a voyeur by going to drive-in restaurants and by taking photographs of the facades of new houses. They’re not sociological; they’re almost a celebration, although that, too, can get out of control. Just look at how frightening the outskirts of Calgary are. But at that point it was a new phenomenon. I was also interested in the role that Godard was playing in post-World War II culture. I was intrigued by upper-lower-class people becoming lower middle class. One of my favourite writers is T J Clark, and he talks about the revolutionary nature of petit-bourgeois culture.

I found the photographs you took in New Jersey quite elegant. How much did the aesthetic value matter to you? Weren’t you using a Kodak Instamatic?

I did go to a 35 mm after the Kodak. But what I was doing wasn’t anti-Minimal art. I was trying to make Donald Judds with photographs.

You have referred to the therapy involved in the personal becoming political. Did you think of your work at the time as political?

I thought of it as subversive but not necessarily political. In other words, I was trying to undermine the political through parody and humour.

Body Press, 1970-1972. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

One of the things that struck me about Body Press, 1970–72, is how awkward the camera is to handle. You’re trying to do something intimate, and you have to deal with this cumbersome piece of technology.

The early films were done with Instamatic Super 8 cameras and I wanted to get a much more aesthetically beautiful film, so that’s why I used that camera in Body Press. I don’t think it really worked. It was the last of the films I did. What was interesting is that the mirror cylinder comes back in the Dia Art Foundation piece. I got very interested in anamorphosis and, in a certain way, my work became baroque. Also, it introduced the element of time. Rodney Graham got that exactly right in the interview in the “Beyond” exhibition catalogue. Time became important, I think partly from drug culture, as well as from the music I was listening to, people like Steve Reich and La Monte Young.

Did you know Rodney Graham from the time you spent in Vancouver?

Yes. Jeff Wall and Ian Wallace got me to Vancouver to teach, and when I first saw Rodney’s Illuminated Ravine I said it’s better than Michael Heizer. I also realized it was very Canadian because it had a power generator. But I thought he was one of the best artists I had seen, and for a long time I got him into every show I was in. In the beginning, I wasn’t picking up on his humour; now it’s the reason I love his work. He also deals with history. The artists I like are not doing neo-’60s art, but are actually involved with real history. Walter Benjamin talked about artists who are “just-past.” Paul McCarthy is another favourite artist of mine—I have a drawing of his where he re-did Michael Jackson’s Bubbles. He was dealing with the ’80s, whereas people like Jorge Pardo look to the ’60s. They don’t deal with the just-past.

You raise a distinction between the just-past and the instantaneous?

I got away from instantaneousness. Artists in the ’60s, like Lawrence Weiner, talked about getting in touch with the immediate, with the here and now, and I realized that was a mid-’60s paradigm which I did believe in. But then I got much more involved in historical references. So with the Dia piece I was trying to change the Dia into an outdoor ICA. What I made was a 1970s alternative space that could be used for performances and an ’80s public atrium with a coffee bar. In that coffee area I had performance and music videos that artists had made in the ’70s. It was the time of Neo-Expressionism and there were no more alternative spaces. What I wanted was to acquaint people with the history of the ’70s.

A lot of your work can be described within a binary framework. I often see it as being about control and then chaos. Do you look at the work dialectically?

I’m more interested in Russian Formalism. I began as a structuralist but then I broke with it. In the first video piece, Present Continuous Past(s), 1974, there is a structuralist element because I’m showing the relationship between the mirror, which is instantaneous present time, and video time delay. So there is a kind of dialectic contrast. But I didn’t have any knowledge of the Structuralist film movement. My biggest influence was Michael Snow in Wavelength and La Région Centrale. The difference was that he used a machine, and because of Nauman, I was more interested in using the bodies of the performers on camera. And even though Michael’s work was rudimentary, it was still more high tech than the low-tech work I was doing.

At the risk of being a chauvinist, you seem to have been influenced by Canadians.

At one point I was influenced by Marshall McLuhan, but then I realized how much he took from Walter Benjamin. He was a brilliant scholar and he put together a very enticing mix. The interesting thing about Canadian culture is you’re a listening post; you see American media culture and comment on it. So I think SCTV was pretty amazing. A lot of what I’m doing is what Godard was doing with his commenting on culture in general. But I was in Canada during a very important period, and I seem to have picked up on some of the most interesting things in Canadian culture.

Still from Rock My Religion, 1982-84. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

What about the time you spent at NSCAD?

It was complicated. They had been doing lithographs by artists at NSCAD, and I suggested they do a book program, which they established with Kasper König overseeing it. A number of the titles they published, like Steve Reich, Michael Asher and Dana Birnbaum, were my suggestions. Judd’s Complete Writings was my initiative because I was so interested in artist-writers. After my gallery went out of business, I went to the library and copied out all of Judd’s writings in longhand. The other thing I did in Halifax had to do with teaching. They had people coming in for short visits for two or three days, and I suggested they do a trial teaching situation where I would do the first three weeks and the last three weeks. I also suggested they bring in people who had never taught before, so Jeff Wall, Dana Birnbaum and Michael Asher came in. I also got Martha Rosler there. But then Nova Scotia changed. There was a group of people, including some feminists, who were politically correct and they started trashing me. The core of the people at Nova Scotia was a boy’s club, not unlike Vancouver. I was very much a feminist, had been all of my life, and had brought in fifty per cent women, but there were people who really disliked me at Nova Scotia. I’ve never been invited back. The same thing happened when Lynne Cooke came to the Dia. She hated the piece and now it’s in storage. Normally at the Dia people make a piece and then they sell it. But my work was actually site specific. I think it’s territorial; when someone comes in they want to have their own program. I’m kind of a provocateur. I tried to subvert the Dia’s elitism, and it worked for a little while and then it stopped working. Institutions go back to being what they were before.

When did you decide to make your first pavilion?

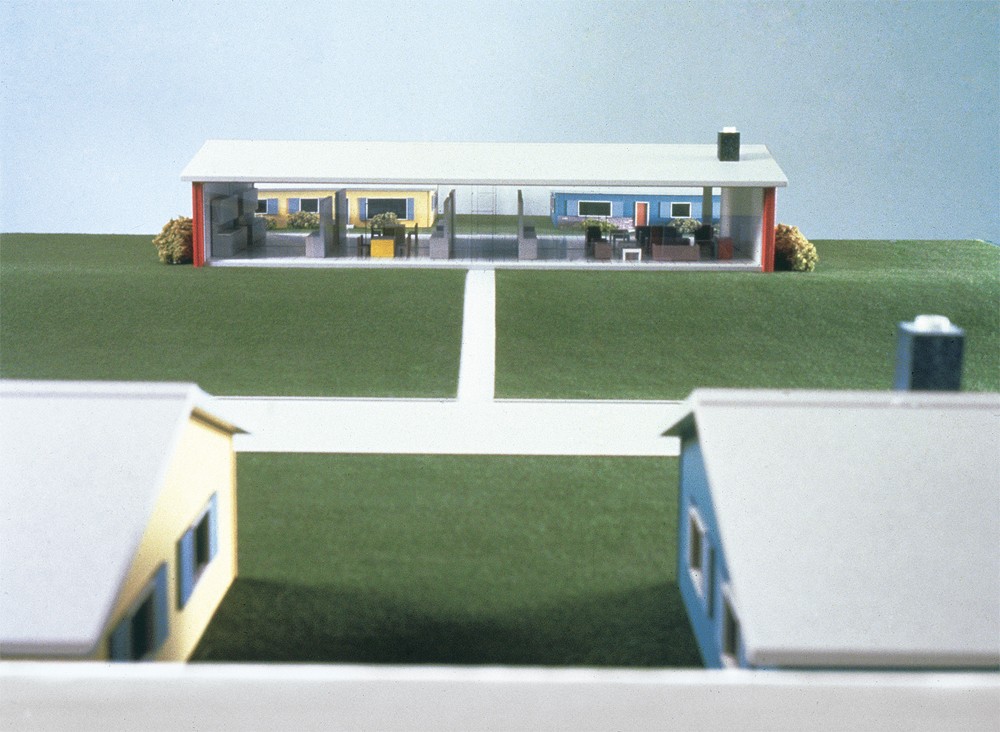

It was the piece done in 1976 for the Venice Biennale, called Public Space/Two Audiences. It was based on a video piece I did for shop windows in an arcade, but here I made the spectators place the goods in the showcase windows because every national pavilion at the Venice Biennale is a showcase for the main artists of that country. I had people looking at each other in place of objects. I thought the piece worked very well because it had the white walls enclosed, but then I realized the white wall referred back to the white cube. So two years later when I had a show at the Oxford Museum of Modern Art, I decided to do eight architectural models that were halfway between art and architecture and sculpture. I had seen a show of architectural models at the Leo Castelli Gallery by the New York Five, and I thought, “Why couldn’t artists do architectural models?” What I did with Alteration to a Suburban House, 1978, was I took away that white wall from the Venice Biennale and made it almost a window, so it became more like architecture. It was work that was actually on the cusp between art and architecture. The pavilions got very stereotyped as pavilions, but a lot of that work is quasi-functional, like Café Bravo, 1998, in Berlin and the Girl’s Make-Up Room, 1998–2000. Instead of being against museums as Daniel Buren was in a rather dumb, simplistic way, I realized that museums are amazing social spaces. So when I was locating the Heart Pavilion, 1991, in the Carnegie International, I recognized that Pittsburgh is a very tough steelworker’s town, which is why Warhol didn’t like it, but it’s also the home of Hallmark Cards and the beginning of the Midwest. So I have this heart pavilion, which is a kind of romantic pickup situation, and the Girl’s Make-Up Room, in the lobby. I did a piece for Kasper König’s Munster Sculpture Project 12 years ago, my Children’s Daycare, CD-ROM, Cartoon and Computer Screen Library Project, 1998–2000, so kids could educate themselves and have fun. I realized that the most important thing in museums in the ’90s was the education program.

I’m surprised that this is your first retrospective in America. Why has it taken so long for that to happen?

Actually, this show began in Los Angeles because I pushed it. I realized that artists in LA are interested in my work, so I contacted Paul Schimmel. My imitators do very well, but there’s never been interest in my work, partially because it was too early; ours is a media culture and I didn’t trademark myself. Also, I’m known as a writer. In a recent interview with Benjamin Buchloh, Carl Andre said I’m not an artist because I’d written about him. My timing is always wrong because I initiate situations and then I move into other areas. But no one has bought any of those architectural models. I know I’m popular because every time I have a show it is mobbed with people. It’s odd because the work sells in Japan, where I was 30 years ago, and in Belgium, but not in the rest of Europe. ** You knew from the start that the pavilions were crossing over into the terrain of architecture as well as being an object? At the same time you have said that you’re not a sculptor and you don’t like sculpture. Early on were you more accepting of the fact that they might be perceived as sculpture?**

I never thought about it. They are a hybrid. One of my dealers thought he could sell my work by making them more like sculptures, but it never worked. When I show them now I show them with the videos, since they function so well as display situations.

The critic Mendes da Rocha says that geography is the primary and primordial architecture. Because your work is very often site specific, I wonder how much the notion of geography or place plays into the kind of piece that you make?

It plays an enormous role, especially in Europe. I have to say that European socialism had been very important in the ’80s. I did a lot of things in France because Jack Lang regionalized cultural institutions, many of which were in old gardens with chateaus. As a result I got very involved with landscape architecture, which a lot of my pieces are. I also realized that many people who came to see my work in France during the summer were often parents, camping out and then looking at art that way. So the whole idea of art as entertainment and education for these summer shows became very important.

Empty Shoji-Screen Pergola/Two-Way Mirror Container, 1992. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Empty Shoji Screen Pergola/Two-Way Mirror Container, 1991, the piece you did in Japan for Sol LeWitt, both acknowledges LeWitt and also looks Japanese.

It’s a shoji screen without the paper. You also see those lattices in family-oriented restaurants just outside the big city, so they have this whole suburban idea of pastorale. I did another piece for the Hirshhorn that has the grid framework but with a curved element, which distorts the Sol LeWitt. The other interesting thing about the grids is that when I put them outdoors I get shadowing that changes during the day, whereas Sol’s earlier grids are lit from the interior and people walk around them and that produces the shadows.

Your piece, Two-Way Mirror Punched Steel Hedge Labyrinth, 1994–96, in the sculpture garden in Minneapolis, seems to mediate between nature and culture. Were you interested in this mediation between what is constructed and what is natural?

When I deal with pavilions I have to deal with them historically, which means going back to Marc-Antoine Laugier’s “rustic hut,” which was a utopian response to the destruction of the city. It was a kind of heterotopia. I also want to do a mix of historic landscape architecture and suburban architecture, so the use of hedges is very important. If you go to a city like Vancouver, it’s all hedge culture. What I noticed when I was in Vancouver, where Jeff Wall lives in a very elegant house, is that just on the other side there are houses that were built during World War II which have these have little gazebos. So through them I became interested in the suburban gazebo.

When I look at the pavilions, like the Fun House for Münster, 1997, I keep coming back to this idea of play. Is that still a quality that interests you?

Absolutely.

You have described yourself not as political, but as subversive. Do you still regard yourself in that way?

I did a piece in Basel for Novartis, the huge drug company, and they have hired many of the biggest names in architecture. There’s also a green area designed by Günther Vogt, a wonderful landscape architect. It’s a place where people who attend the university connected to the company and who work there go to eat during the day. But on the edge of this park is a rectilinear building by Kazuyo Sejima, whose work I think is very corporate and very boring. So what I’ve made in the centre of the area is a work that has one straight line bisected by a curved line. The curved line relates to people’s bodies and also to the sky, but it also distorts the Sejima. It’s the middle of a corporate situation, but I want to play with the corporate situation. Sometimes you can do things that are subversive and sometimes they turn out not to be so subversive.

We noticed yesterday there were times in the exhibition when things seemed slightly disorienting, almost to the point of being vertiginous. Looking at some of the work, we occasionally felt slightly dizzy. Did you intend that?

I think you can say they are on the edge of being schizophrenic. It’s like a funhouse situation. It also has to do with being a small child and being frightened by normal things. The work is also cinematic and has a lot to do with the loss, and then the finding, of ego in relationship to other people. I think people engage with each other in their own image and when you see your image you’re a little fearful of being seen by other people. Also you lose a sense of yourself and then you gain it back again. This often happens when you identify with characters in film.

One of the things you have done so effectively is use the mirror as both reflection and transparency. Have you consciously worked variations of those two ways of seeing?

It comes from looking at two-way mirror glass, which I used in some of the video pieces as one-way mirror. I want to undermine the corporate use of the one-way mirror so whatever side gets the light is reflective, and on the inside it’s transparent. So it is a surveillant situation. It also is an alibi for the corporation. Jimmy Carter was developing an ecological critique of corporate power in the ’70s, and corporations cut down on air-conditioning costs with two-way glass, so they were helping the environment. The outside of the building shows the sky, so the alibi comes in the corporation identifying with the sky. What I wanted to do was a pleasure pavilion that would be a critique of that. I think all my work deals with the city as a form.

Alteration to a Suburban House, 1978. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

When you do domestic architecture—I’m thinking of Alteration to a Suburban House, 1978/92—you elaborate on notions of privacy and disclosure. You also do it in Video Projection Outside Home, 1978, where we see outside the home what the family is watching inside.

The piece with the TV monitor outside is really about suburban culture and also lower-middle-class suburban culture. If you’re an Italian American, there is often a little Madonna statue or a cupid, and if you’re German American, there might be a dwarf or a gnome. Venturi did a show called “Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City,” showing the ornamentation these families have outside, so when the video projector came into use I thought it would be interesting to show what people were watching by looking through their picture windows into their living rooms. It could be cartoons for kids, it could be educational television or it could be pornography late at night.

This returns you to the idea of art as anthropology.

Exactly. It’s about the family structure. They also have to do with reading architecture because the Alteration of a Suburban House is a combination of Mies’s Farnsworth House, which was in the middle of nowhere, and Venturi’s interest in relating to the surrounding suburban houses and the situation on highways with billboards.

It becomes clear when you show slides of influential figures how important Mies was to you.

Initially, I was critical of Mies because Venturi was against him for being so corporate, but then I discovered the great work he did in Europe. It turns out all almost all the work he did there was landscaped, including the Barcelona Pavilion. I think he was very influenced by Schinkel. Mies’s Tugendhat House, which I think is his best work, has a conservatory on the side and is landscaped. Along with Pierre Jeanneret, Mies deals a lot with the mirror stage, because you see an image of your moving self. It’s also about the inside and the outside as a garden pavilion. So only later I discovered my work was actually like Mies, just not from the late American period.

How important is pure phenomenology? There is a certain purity to the idea that you just experience the thing in the moment?

That was an idea in the ’60s but I broke with it. I may have been interested in the idea of the instantaneous at one point, but now I’m totally against it. I think work relates in time. So the Dia Foundation piece changes as the skyscape changes and as you walk around it.

So in one sense now you’re engaged with history?

Absolutely. Not historicism, but history.

And a history that is self-reflexive. It’s actually your own history that you’re engaged in?

I don’t really think about that.

And yet isn’t the work necessarily an exploration of your own way of thinking about how we are in space? How we perceive ourselves and how we are perceived?

I actually don’t have these thoughts in my head.

So do you learn from each pavilion and carry that knowledge on, or is each pavilion a response to the specific characteristics of place and site?

Well, I often get ideas looking at architecture in the city and in looking at architecture books, which I put in my notebooks, and if I see a site I might take one of those ideas and modify it to suit the situation. For me, it is a combination of what I carry to the project and what the place gives to me. I think most architects work the same way.

Half Square/Half Crazy, 2004. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Do you think of yourself as an architect?

No. I think that’s ridiculous. I never went to architecture school and it’s a matter of knowing your limitations. All my work is a hybrid. I’m in a hybrid situation. Architects love my work, and my books sell out very quickly because architects are often involved with the work. Also, it is a great hobby for me. I know the passion of Rodney Graham is to play music, which we often disagree about, but I think my passion is architecture tourism. I’m very happy that I know some of the best architects in Japan. I love Itsuko Hasegawa’s work. So I see a lot of my work as a passionate hobby.

You’ve said the same thing about photography. It makes you sound like an amateur.

Not in the way of Rodney Graham’s gifted amateur.

What was your attraction to rock music? Was it the structure of it or the chaos that interested you?

It was a beautiful pop form. Also, rock groups are communal in a certain way, and I’m a very isolated type of person, so I liked the sense of community. But I also wanted to be a writer. I had read Leslie Fiedler and I think that the best writers after him were in rock n’ roll. Paul Williams with Crawdaddy! and early Greil Marcus. I thought that writing about rock music was a way into writing. My favourite writer is Jon Savage from England who wrote the definitive book about The Kinks.

Did you read Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel?

Yes, everything he wrote. You know, he’s still in Buffalo.

Do you know his outrageous comment that the family that blows together, grows together?

No, but he does exaggerate a lot.

You don’t systematically approach reading or research?

I did get involved in architecture because I felt that art criticism was very banal and some architects, like Aldo Rossi and Venturi, were brilliant writers.

I’m continually struck by how important writing is to you as a provocation or a catalyst.

I don’t do too much of it anymore. I rely on what I’ve already read.

You have said that all of your work is a critique of Minimal art.

I think that’s a bit of an exaggeration. It’s where I began. Minimal art was in opposition to Pop art, and I was influenced equally by Claes Oldenburg and Sol LeWitt. In a certain way, Oldenburg was also dealing with parody and with cultural issues.

Do you think that much of what you have done has been, in a much broader context, a cultural critique?

Yes, everything is except for the sociological. I think sociological critiques are too reductive. Every time you do a work you try and critique your own work by undermining a certain built-in situation. What I like about these big European shows, like “Documenta,” is that they have a theme, which is sociological and educational. The idea is to play with that, maybe undermine it, but still stay within the category.

Double Exposure, 1995-2002. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

What do you think of the show here at the Whitney?

I designed it myself, and I was thinking that the main space should be like a lobby. I designed works for lobbies, like the Girl’s Make-up Room, which should be in the area just before you go into the museum for children to play in and for people to experiment. It should also be smaller in scale so it would act as an introduction to the rest of the show. I thought the performance area was a little cramped and you couldn’t hear some of the works. They should have had headphones. But I think it was a challenge because I had a big retrospective in Europe that was badly done, and so I wanted it done here so I could get it right.

When you talk about hybridity is that something that you aim for or is it something that just comes with the nature of the work you do?

It comes with the nature of the work. When I did these things for magazine pages, the idea was they could work in the place of a gallery, as magazine structure, as art structure, but they could also be seen as writing.

So you don’t have to consciously set out to layer a piece; it’s layered by its very nature?

Yes. But I don’t see it from the outside as you do. I don’t really think about it. I like to get into new areas and I like them to be in a borderline situation, rather than definitively one thing.

You talk about taking an idea and exhausting it, in a sense working it out.

Yes, that is conscious. But I’m having a big problem with this retrospective because I can’t be a rebel anymore. I’m always undermining situations, and a lot of my pieces never get done, like the Swimming Pool/Fish Pond, 1997, and this great piece, Double Exposure, 1995–2002, which we didn’t have the model for in the show because I sold it to the Serralves Museum in Porto. You can actually see time changing through it—the time of day, the different seasons. It’s a beautiful piece. For years, I wasn’t able to do it, but now it’s in a very remote area in a garden in Porto.

Are you disappointed that these pieces haven’t been realized?

Well, it fuelled my anger to do new pieces. I have never had a really easy success.

“Dan Graham: Beyond,” was exhibited at the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis from October 31, 2009, to January 24, 2010. It began its tour at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles from February 15 to May 25, 2009, and travelled to the Whitney Museum of American Art from June 25 to October 11, 2009.