Breath Taker

The Filmic World of Aïda Ruilova

Interview by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh / Introduction by Robert Enright

“I have always been interested in the culture of film and movies,” Aïda Ruilova says in the following interview. While her film tastes are omnivorous, she has developed a special affection for tales that touch on suspense and horror. From the time her father took her to see the John Carpenter movie The Thing, 1982, when she was nine years old, her imagination has been captivated by films that are most entertaining when they are most anxiety-provoking.

She has said that she “gravitates towards mystery” and as a result she has taken artists and directors who move in that ambiguous terrain as subjects. In a conversation published in Interview magazine with the American director Abel Ferrara, who is the subject of her unconventional documentary Head and Hands (my black angel), 2013, Ferrara, he describes the characters in his films, like King of New York, 1990, and Bad Lieutenant, 1992, as being in “the same family of black sheep.”

Aïda Ruilova, Inside of Me, 2016, paper and velvet, 38 x 54 inches. All images courtesy the artist.

Ruilova is obsessively interested in that dark family line. She has made a short film about Carlo Mollino, the Italian architect, designer and photographer of a thousand erotic images of women, whose motto was “everything is permissible as long as it is fantastic;” as well as a pair of short films about Jean Rollin, the French fantastique auteur who mixed eroticism and blood in classic films like The Nude Vampire, 1969, Lips of Blood, 1974 and Fascination, 1979.

In Life Like, 2006, shot in Rollin’s Paris apartment, Ruilova compresses their voices in a film that combines excerpts from his films with shots of an actress who is stroking his face and straddling his body while he plays dead. His cool body heats her up and she engages in an act of simulated necrophilia. It is a short tribute film made in the manner and on the matter of the master.

Ruilova strives for tension and anxiety in her films, and one of the ways she captures those qualities is through her use of sound. Her early musical training was as a classical pianist and she was a founding member of Alva, an all-women experimental music group. (Their first album, released in 1997, was called Fair-Haired Guillotine). Ruilova’s first films were single-channel videos; the shortest, no, no, 2004, is 13 seconds; the longest, Life Like, is less than five-and-a-half minutes. While these films were short on duration, they were long on aural punch. When she used language in the single-channel work it tended to be percussive, more about rhythm than syntax. Many of these videos employ music, or implements of music, as integral components in the meaning and sounding of the piece. In Oh no, 1999, a woman walks on a guitar and repeats the phrase “oh, no” in varying tones of fear and apprehension; in You’re Pretty, 1999, a long-haired shirtless man attempts to dismantle an amplifier while reciting “you’re pretty” over and over. He also drags a vinyl record along a rough concrete basement wall. The physical spaces in Ruilova’s video and films are materializations of psychic spaces; her characters move in rooms that are compressed brain scans.

Ruilova’s work is full of objects that remind us of bodies. In “The Pink Palace,” her recent exhibition at Chelsea Marlborough in New York, an inflatable called Rocky looks like a huge, breathing organ; she made it by conjoining a pair of boxing gloves in the form of a heart. But you would be ill advised to consider the shape to have any sentimental attachment; when a heart appears in her work, damage is not far behind. The bed in the room in Goner, 2010, is heart-shaped, and what occurs in that space is what Michael Ondaatje would call romancing with a knife.

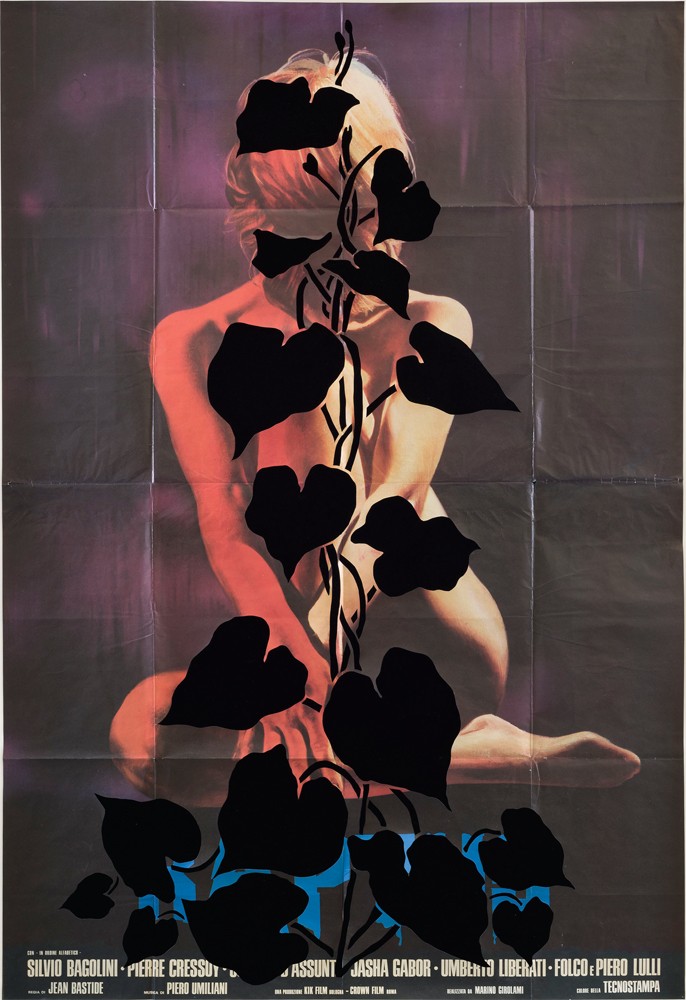

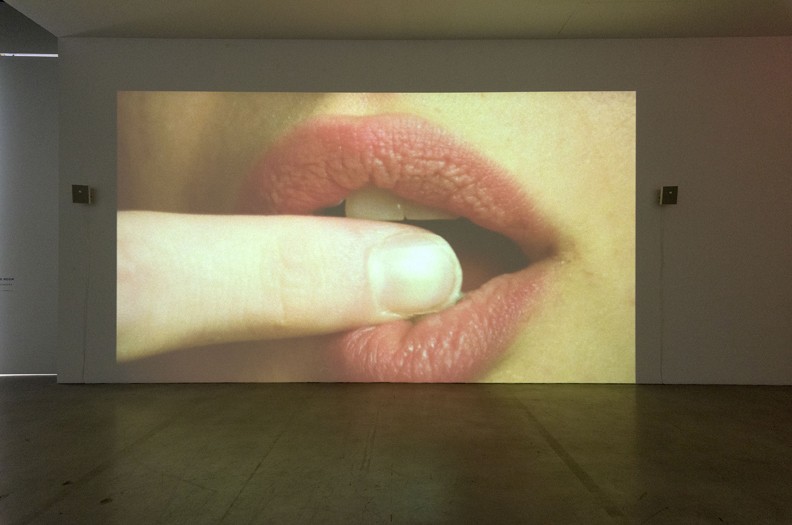

Something similar happens in the delicately sinister cuts she makes on the altered ’60s and ’70s erotic movie posters in her Marlborough exhibition. She is executing a fragile aesthetic surgery in which the black velvet backing that emerges can as easily become a funeral shroud as a sensual bolt of cloth. But Ruilova is equally capable of making the body a location of erotic fascination. Her 24-footlong video projection of a woman’s mouth being touched by a male finger is utterly compelling. The piece, called Immoral Tales, 2014, takes its name from a film by Walerian Borowczyk and its visual pedigree from Man Ray’s Observatory Time – The Lovers, 1936, a massive 8 x 3 foot painting of Lee Miller’s lips (she was his departed lover).

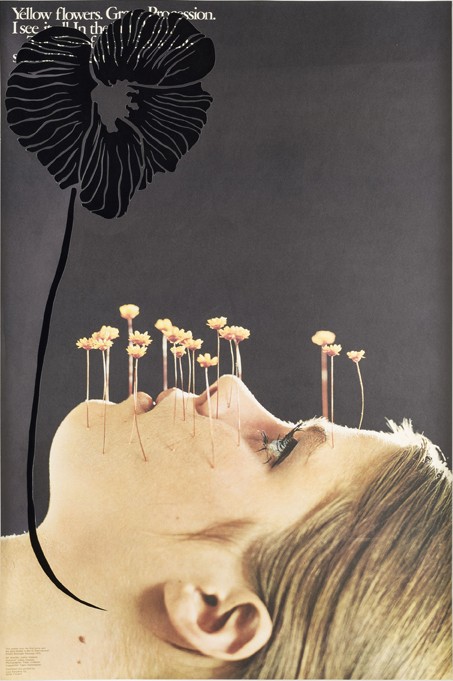

Yellow Flowers. Grave. Procession., 2015, paper and velvet, 47 x 32 inches.

But Ruilova’s body part looms over what Man Ray achieved. Her mouth (the lips belong to Sonja Kinski) is both a site and the sight of desire. What is even more seductive is the visceral breathing in her film loop; it seamlessly moves through inhalation, exhalation and excitation, including a shudder that is discreetly orgasmic.

There is an edginess to pretty well everything Ruilova does. In her interview with Ferrara she says that as an artist, “every time I make something, if I’m not on the edge, pushing myself and taking a million risks, then it is not going to be good.” That self-positioning is most apparent in Goner, her 12-minute-long exploration of physical and psychic trauma. In the film, Sonja Kinski is a victim of someone or something, we never actually find out, but it’s menacing is devastatingly effective, using the tricks of horror films with such economy that the viewer is kept in constant suspense. “Goner starts like a slow bleed and then accelerates,” she says. It ends up moving at such a velocity that it pulls the air out of your lungs. “Time is fundamental to pacing,” she adds in the following interview, “and breath is fundamental to the body.” By that measure, Goner is fundamentally breathtaking.

Aïda Ruilova has had 24 one-person exhibitions since 2000 in the US and Europe. “The Singles: 1999 – Now,” a five-city exhibition organized by the Contemporary Art Center in New Orleans, toured to the Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff in 2009. Her most recent exhibition, “The Pink Palace,” was at Chelsea Marlborough in New York in February and March 2016. Ruilova was a Hugo Boss Prize Finalist in 2006 and was included in the 2004 Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale in 2003. She was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, and was educated at the School of Visual Arts in New York and the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The following interview was conducted in New York on June 29, 2016.

BORDER CROSSINGS: You did an artist’s book with Jean Rollin didn’t you?

AÏDA RUILOVA: I have an archive of film materials and I decided to put together a book from that archive. Jean and I had written letters to one another for a long time, so I included materials that related to the film I did with him, a selection of our personal letters, film stills and also images he had mailed to me. So for example, the cover is an image he had sent and then inside there is a photograph of Salma Hayek, who had come to visit my studio. I had a Jean Rollin Fascination poster up and she put on my monkey fur cape and posed in front of it. It felt like she was transforming into one of the women in Jean’s films. And there are images of the actress, Tamaryn Brown, and Jean from my 2005 film, Life Like.

Tamaryn, who resembles you, is a surrogate of sorts?

She is, and she also resembles the women in his films, so Jean and his films became an object with which to work. We met through his son over email and the first time I visited him I made a short video called Tuning, and then a couple of years later, after we had written letters and continued to talk, I made Life Like, which at five minutes was a long film for me. I had been making very short works that would last between 10 seconds and a minute. So five minutes was epic. Back then I was interested in this idea of compression and what happens when a viewer enters and walks through a space, as opposed to sitting with a film or video for an hour. There is a big difference in how it needs to operate and function, and how you want the viewer to feel when they’re sitting with the work.

Raptus, 2015, paper and velvet, 79 x 55 inches.

The time compression is still there but you do something different in the longer film; you collapse segments from his films into the sequence where your actress plays out the idea of necrophilia with his body. It has a narrative arc.

It does have a narrative arc and that was what I wanted to start exploring. I had been making work in a certain way and to some extent I wanted to mimic his films. By inserting my own work within his body of work, they informed each other. His films are meditative, static, even drone-like in their pacing and I wanted to insert our voices into a film that used his whole oeuvre, compressed in a nutshell.

And he happily plays himself as a dead body, so necrophilia does enter the narrative.

Yes, he kept falling asleep. Most of his films are vampire films and having Jean play himself dead turned his physical body into a space that I could take from. His first film, The Rape of the Vampire, inspired me. Jean is part of the generation of filmmakers in France who could cross over between art and porn; in the late ‘50s and ‘60s there were theatres where someone like him could show his Euro-horror and sexploitation films as art and people would go to see them. He was inspired by serials and B films, a place where someone like Roger Corman was operating.

I read that the first film your father took you to, when you were nine years old, was a John Carpenter horror movie.

Yes, The Thing. I don’t know why he took me to that film. I remember him looking at me to see that I was okay and sometimes he would cover my eyes and I would complain, protesting that I wanted to see. I have always been interested in the culture of film and movies. I wanted to be a director when I was younger and I wanted to get out of Florida. I thought I could do that by going to graduate school at NYU, but when I visited I realized that holding lights one day and doing the camerawork the next day wasn’t what I wanted to do. So instead I went the art route. In my undergraduate program I was fortunate to have people like Peggy Ahwesh and the Kuchar brothers come to visit. It was outside the normal film world, when there was still experimental cinema and experimental video makers. There weren’t DVDs yet, so I was right on that cusp when everything was turning digital. I was fortunate to learn that tactile history, and I liked the freedom of entering into film and video in that way. Film is the ultimate for me because it’s a sculptural medium, and you have to work with space and time, not to mention whatever you’re interested in seeing and going after as far as the content is concerned.

When you did your master’s degree did you major in painting or drawing?

Oddly, the School of Visual Arts didn’t have a video program at the time, so I was in a program called Photography and Related Media. It consisted mainly of photographers, including Stephen Shore and Collier Schorr. Sarah Charlesworth was my main teacher. They had a digital video editing system, which is why I went into that program. I was only able to work in video but a lot of the critiques were photography critiques because the program was comprised mainly of photographers. They would do video on the side, but video was my main thing. Sarah was always supportive in understanding that. I made my early videos in her class, where I remember showing Oh No. Nobody was making work like that; what was popular was long-form video and video installations. I didn’t actually understand what I was going after; I was just doing what I wanted to do.

The Stun, the film you made in 2000 based on Bacon’s 1953 portrait of Pope Innocent X, indicates that even when you gravitate towards pictorial art, you discover something in it that allows you to move into the terrain of horror. Is that naturally where your sensibility moves?

I am definitely interested in what an image can do and how it can manipulate a viewer. There has to be some tension or anxiety in an image for people to be interested, me included. For instance, now that I am working in a longer time format it’s important to be aware of how I handle the balance and pacing between quiet and fearful moments. In Goner you have quiet moments, so when you inject the tension or fear it has to be relative to something and the viewer has to feel the contrast.

…to continue reading the interview with Aïda Ruilova, order a copy of Issue 140: Sound, Film, Photography here, or SUBSCRIBE and receive a limited edition Border Crossings tote, screen-printed late summer 2016 in Winnipeg, MB.

Installation view, Immoral Tales, 2014, super-16mm film, sound, 44 seconds.