Ways of Looking, Ways of Not Seeing

An Interview with Shaan Syed

Border Crossings: I’m always interested in knowing why someone becomes an artist. What was it that made you decide?

Shaan Syed: For various reasons when I was 16 I wanted to change schools and had heard about this arts high school in another part of the city where students were sleeping overnight in cupboards and painting murals on the wall. It sounded really anarchic and crazy and I wanted to be a part of it. So I applied, got in, and it was a revelation. I had always enjoyed making things with my hands, but it was an eye-opener to get an insight into what I could achieve through art and how it could be a vehicle for a dialogue between me and an outside world.

Was that art high school your road to Damascus from which there was no turning back?

Yes. I knew right then that was what I was going to dedicate my life to. There was no question. Of course, I had to do other things to make a living, but from that time on, I knew it was going to be art and, specifically, painting.

What was it about painting?

Painting was a natural draw and I’ve been questioning that draw ever since. What is it that attracts me to look at a flat surface and what makes me want to make marks on that flat surface? That kind of inquiry has been leading my painting since, and I find it’s entering a lot of my teaching as well.

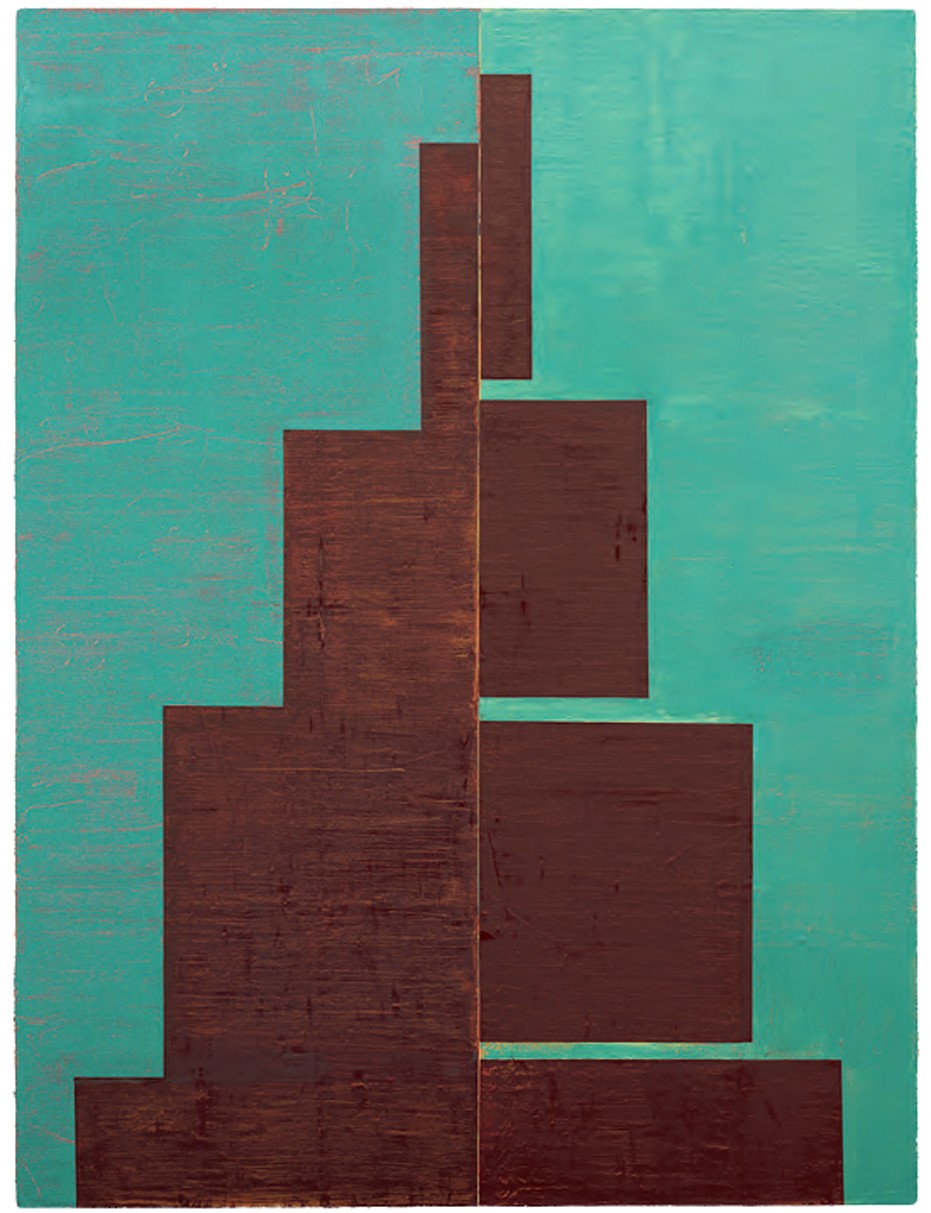

Shaan Syed, Untitled, 2020, oil on linen, 230 x 174 centimetres.

So yours is more than an aesthetic and phenomenological pursuit?

I often relate it to psychoanalysis and the actual idea of desire. There’s a British psychoanalyst and writer called Darian Leader whom I often mention when I’m talking about painting. Instead of asking what the painting is showing us, he asks, “What is the painting hiding from us?” Reversing the question is a typical psychoanalyst’s tool, and I find it’s a useful way to think about the self and painting.

It’s predicated upon the idea that there is an intention to not disclose. So some of what the painting reveals is, in one way, accidental. As the generator of these images, where do you enter that psychological terrain: on the withdrawal and withholding side, or on the revelatory side?

I think I’m finding that out all the time. But I tend to look at painting as a process of making rather than a process of ending up with an image. I know you end up with a picture of some sort, but it’s within the process that the picture gets made. And that process points to some of these more phenomenological and psychoanalytic ideas.

So when you work painterly variations on the minaret, are they deliberate investigations into the difference between a minaret that has a slightly winged top as opposed to a flatter, more geometric top? Is that found in the making rather than being thought about prior to beginning the painting?

It’s not necessarily the architecture of minarets per se that I’m pursuing—it’s the contradictions I see within a specific minaret that connect me to image-making and painting. The minaret of the Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq is the structure that has intrigued me most. I’ve only ever seen it in pictures—it’s a giant tapering snail shell with a staircase that spirals up and around its exterior. As an image it seems to bisect sky and land, and because of its layered tapering spiral, when flattened within the two-dimensional, the silhouette appears asymmetrical. I’m interested in this symmetry and asymmetry, its iconic structure despite the decree in Islam against the icon, and how it functions as a sign. It’s become a significant motif, which has allowed me to do other things and, in that way, it acts as an anchor to one set of ideas that is linked to biography and culture.

…to continue reading the interview with Shaan Syed, order a copy of Issue #156 here, or Subscribe today.