Way of Being: The Art of Lori Blondeau

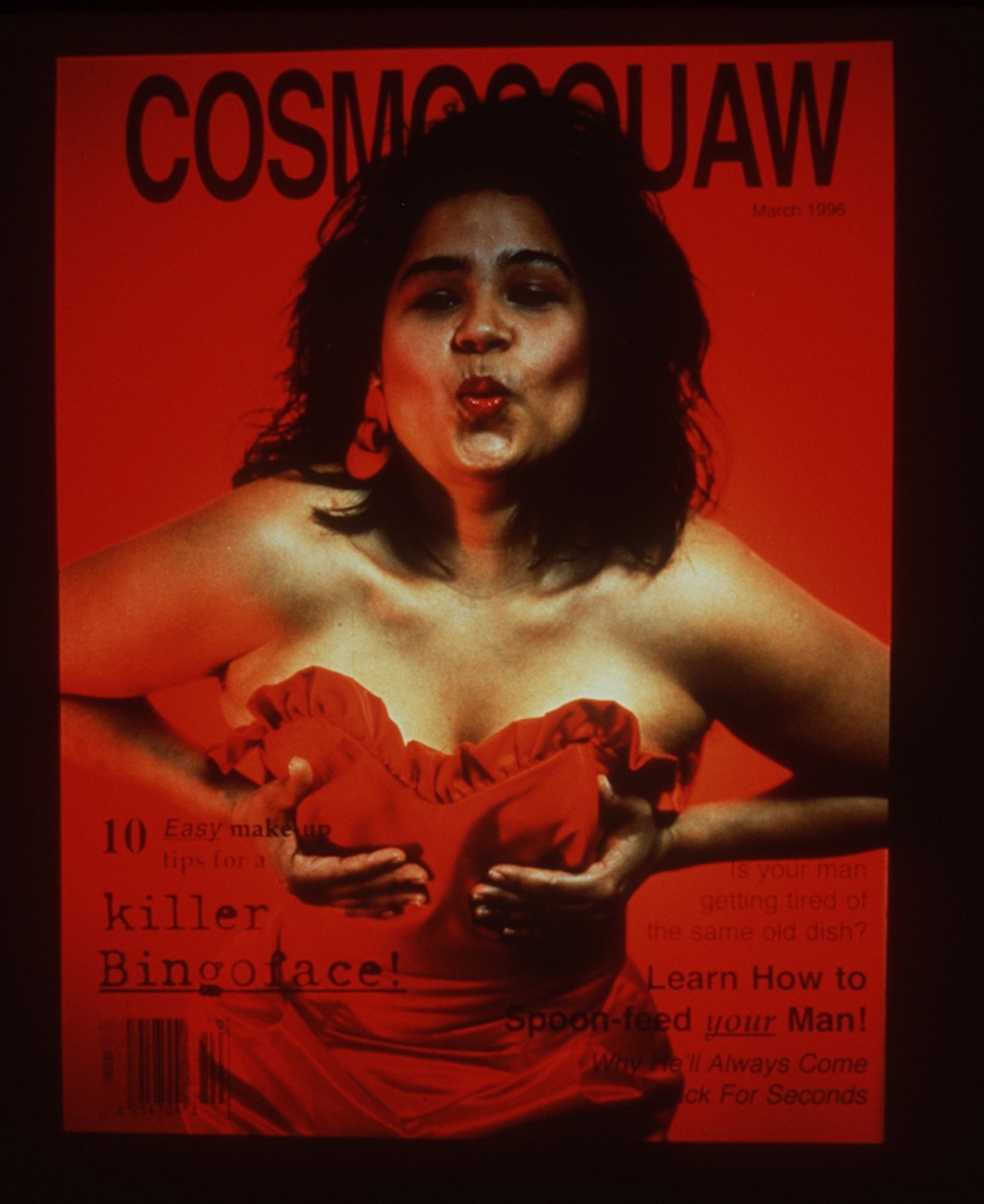

“I think being born Indigenous means you are political,” Lori Blondeau, a 2021 recipient of the Governor General’s Awards in Visual and Media Arts, says in the following interview. “You’re born political because you have to fight for your rights. We’re still doing it today.” This sense of the unavoidable nature of Indigenous politics explains a range of activity that includes making art, curating, starting and running a roving art gallery and having a commitment to social activism. Her career has focused on an integral connection between photography and performance. What they share is a way of using her personal life experience and the history of her culture—she is Cree/Saulteaux/Métis from Saskatchewan—to tell and enact stories, but where they differ is in the way they affect the viewer. A number of the performances, like Are you my mother?, 2002, Sisters, 2002, and States of Grace, 2007, are ceremonial and deliberate in their tone, whereas the photographs, particularly COSMOSQUAW, 1996, and The Lonely Surfer Squaw, 1997, are irreverent and rambunctious. This pair of images (both are duratrans in lightboxes), her best-known works, are justifiably iconic. COSMOSQUAW combines parody with cultural celebration. It mimics the cover of the women’s magazine that Blondeau discovered was reading material at the Native Women’s Shelter in Montreal in the 1980s. The magazine would always include questionnaires that Blondeau saw as “geared for white women. … my co-workers were looking for love in all the wrong places and I decided to make a magazine for them.” Her solution was to Indigenize the look and content of the page. The cover image shows Blondeau wearing a red strapless dress, with a thick, tousled mane of hair and lips pursed à la Betty Boop, and provocatively cupping her breasts.

The text on the cover is Cosmospeak but the content has been customized: “10 Easy make up tips for a killer Bingoface!” and “Is your man getting tired of the same old dish?” If the answer to that question is yes, then the cover offers the promise of a remedy: “Learn How to Spoon-feed your Man! Why He’ll Always Come Back For Seconds.” Spoon-feeding is an understood euphemism for sex, so the woman with her killer Bingoface is set for success. The satire in the makeup line softens to humour when Blondeau talks about the social and cultural value of bingo inside her culture. While she hated bingo, she realized it was “a big thing in my family. My grandma, my kokum, played bingo almost to the end of her life…. I would go because that’s where I could have a good visit with my aunts and my grandmother.… I went for the stories.”

Lori Blondeau, COSMOSQUAW, 1996, duratrans in lightbox, 27.9 x 22.8 centimetres. Courtesy of the artist and John Cook.

Her images, characteristically, never read only one way. The photograph of The Lonely Surfer Squaw, in which she sports a red fur bikini and tall wrap mukluks and holds a pink Styrofoam surfboard, was taken near the Queen Elizabeth Power Station on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River. It is the site of the infamous Starlight Tours, where Indigenous men were taken to the outskirts of the city by Saskatoon Police officers and abandoned in the deadly winter cold. The practice caused the death of at least three Indigenous men, including Neil Stonechild in 1990. In the shadow of that piece of history, the surfer girl has reasons to be lonely beyond her wintry solitude.

There is a telling moment in the interview where Blondeau is talking about how she uses the word “squaw” in her art and life. She doesn’t regard her understanding of the word as part of a process of linguistic or historical reclamation. “I don’t need to reclaim it because I was redefining the bastardized English way of saying it. I never think we have to reclaim our language because our language is always there.” In her words, photographs, performances and teaching, Lori Blondeau continues to insist upon the present articulation of that indomitable voice. The following interview was conducted by phone to Vancouver on May 13, 2021.

Asiniy Iskwew, 2018, inkjet print on Dibond, 167.6 x 111.8 centimetres each. Courtesy of the artist and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (Crown- Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, CIRNAC).

Lori Blondeau: I grew up in a family where the women had a strong influence on the family and how we were raised and what we were taught. The power resided within my mother’s family. I think the majority of Indigenous people across different nations, across North America, are matriarchal. My grandfather on my mother’s side, who was a powwow dancer, came from a very strong family also. It was how the structure of our culture functioned, and there was never any questioning about people’s roles. Everybody, even the kids, had a role. But it was the women who played the strongest role within our culture, and it totally influenced me on so many levels.

Border Crossings: At any point did you consciously decide that you wanted to be an artist?

No. I just knew that art was a part of our way of being as Indigenous people. Making art was what Edward Poitras, my brother, did and my parents supported him. There are six of us and they supported me and all my siblings. We were taught that you’ve got to do what you’re passionate about. That’s really where my parents’ activism came in. We were allowed to do what we wanted to do, whether it was being a carpenter, social work, education or being an artist. They never questioned our choices. I did contemporary dance and then I studied theatre at the Native Theatre School, which is now the Centre for Indigenous Theatre. I knew that my medium was not like my brother’s.

Asiniy Iskwew, 2018, inkjet print on Dibond, 167.6 x 111.8 centimetres each. Courtesy of the artist and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (Crown- Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, CIRNAC).

Narrative plays a role inside your work and one of its dimensions is political. So the seven narratives that you use in Grace (2006) are episodes from your own life, including the birth of your children and your father’s near death. Do you want to elaborate on how story functions in your work and why it’s important?

I think a lot of artists take stories and make art from them. For me, a lot of that story is personal. I was raised being told stories, and coming from an oral and not a written culture has really influenced my production of art. A lot of the stories I tell are my own, so I don’t need permission, but many of them are about my mother and my mother’s family, and I always get permission to tell them. Are you my mother? (2002) took nine years to make. My mom worked on that show with me and when I did the first performance in 2002 for my MFA show at the University of Saskatchewan, all my sisters and my nieces and my kids were there. We put a seat for my mother in the front row, and when I was skinning the poplar trees she started crying. I had to stop the performance. My sisters and my nieces walked through this big crowd and we took my mother into the office of the gallery. I asked if she wanted me to stop the performance and she said, you need to finish it but I’m not coming back out. What triggered my mom was the smell of the poplar trees being skinned because my reserve is on the Little Touchwood Hills, which is the second highest point in Saskatchewan besides Cypress Hills, and it’s all poplar trees. I wanted it to smell like my grandparents’ place because that’s the wood they burnt in their wood stove. Poplar has a very specific smell.

…to continue reading the interview with Lori Blondeau, order a copy of Issue #157 here, or Subscribe today.