Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Vicissitudes of Light

Yelena Yemchuk, Mimi Plumb, Genesis Báez, Seth Fluker, Viviane Sassen

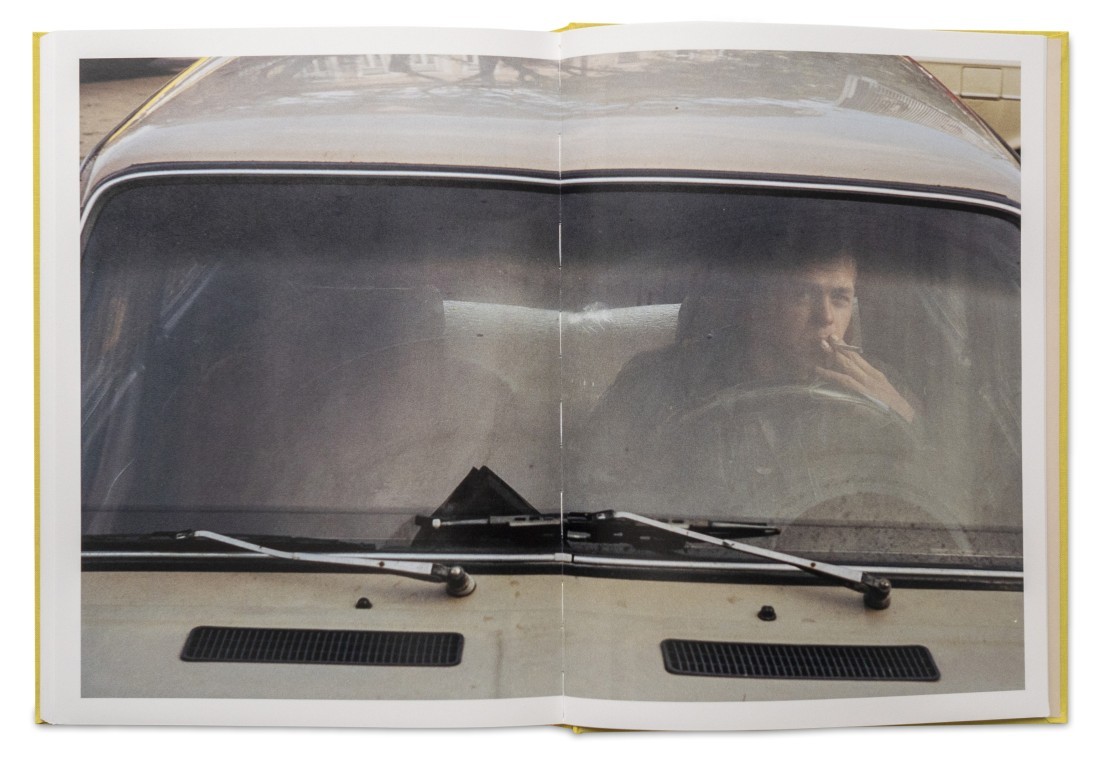

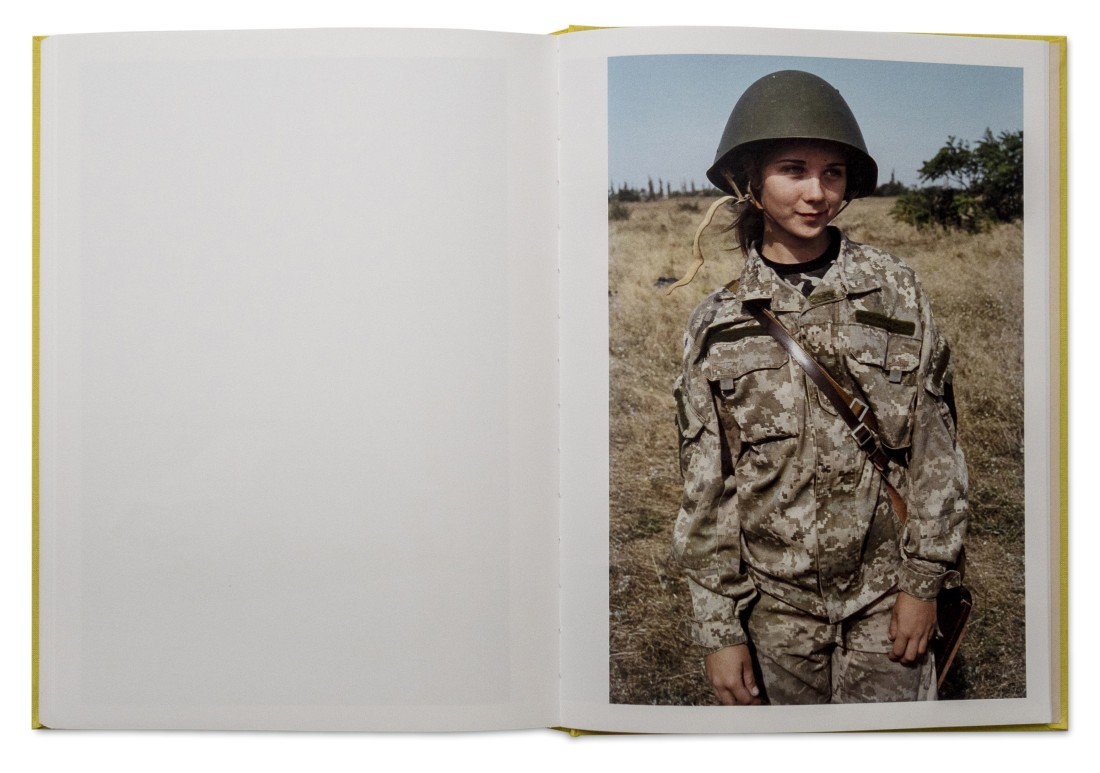

Needless to say, Ukraine has been on all our minds this past year. Its suffering and hardy people have gained compassion and earned respect. So the publication of Odesa (London: GOST Books, 2022), the latest book by the Kyivborn, New Yorkbased photographer Yelena Yemchuk, could hardly be timelier. Not that it documents events since the Russian invasion that began on February 24, 2022. Yemchuk’s pictures were taken between 2015 and 2019. Still, that means this work began in the wake of the Euromaidan uprising, the Russian annexation of Crimea and the onset of fighting in Donbas. So while Odesa is essentially a book of portraits, the shadow of war hangs over the project. If it’s true what the poet Ilya Kaminsky writes in one of the several short texts he’s contributed to the book—that the language of Odesa is neither Ukrainian nor Russian nor Yiddish but a special dialect common to immigrants, and that it “doesn’t have complicated tenses or structures” and that “in our city we change easily from past to present to future tense”—then perhaps this language is something like the language of photography, which is always traversing the present and mixing up the properties of temporality. And so perhaps Yemchuk’s images were already shifting into the future tense to speak of our present. She began with teenaged students at the Odesa Military Academy. “I wanted to document the faces of these children going off to fight,” writes the artist. The project’s scope widened from there, but still, her subjects are mostly young, sometimes children—I noticed only a couple of elders in these pages. A few images shift the focus from people to places and things, but on the scale of the book itself, these remain “background”: Yemchuk’s eye is above all for the mercurial shifts of expression in faces, the flux of feelings they reveal, whether or not they mean to: what this book really amounts to is a poignant depiction of innocence in danger. For those of us whose mental images of Ukraine derive mainly from the work of its most renowned photographer, Boris Mikhailov—a desperately scuzzy, dilapidated, tragicomic vision—Yemchuk’s tender pictures may seem strangely idealistic. Right now, at least, they also feel truthful.

Yelena Yemchuk, Odesa, published by GOST Books, 2022

Yelena Yemchuk, Odesa, published by GOST Books, 2022

Yelena Yemchuk, Odesa, published by GOST Books, 2022

Yelena Yemchuk, Odesa, published by GOST Books, 2022

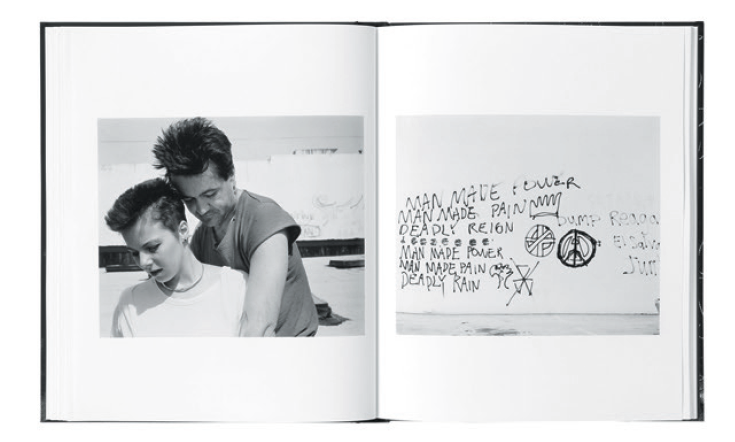

Asked how she knows when she’s got a strong photograph, Mimi Plumb replied, “There are some images that I feel in my back.” I think I know what she means: ones that pass through the eye and the brain to some part of the body that isn’t about looking, though it’s all connected through the nervous system. Plumb makes or finds those images more reliably than most of her colleagues, maybe, in part, because she’s taken her time with them. Plumb’s recent book, her third, is The Golden City (London: Stanley/ Barker, 2021). It’s dated 1984–2020 but the pictures, all black and white, feel both timeless and simultaneous, and as for the city itself, Plumb’s home, San Francisco hardly seems to live up to its gilded nickname—and at times, for that matter, especially in the book’s opening pages set in dry, desolate, rubbish-strewn landscapes, what we see might seem not to belong to any city whatsoever. Eventually the teeming cityscape appears at a distance, seen from a height—a low-slung peripheral neighbourhood close by, skyscrapers promising prosperity much further in the distance. When we finally enter the urban scene proper, it’s a landscape of relentless demolition, of buildings overshadowed by looping highways, of dilapidated walls. The pictures are not unpeopled, but the people—often seen from behind, as if the pictures one feels in the back also come from the back, or masked—remain opaque, unknowable and somehow out of tune with their surroundings. Even the glimpses of nightlife we catch here and there speak of isolation, not conviviality. In a few crowded downtown street scenes, the absence of a horizon line collapses the distance between foreground figures and the faceless architecture that looms over them. This is not the San Francisco we picture today as the second-most-expensive city in the US, but its bleak surfaces conceal a beauty that luxury does not know; time seeps into the bones of the image and tells its unadorned truths in the form of a plotless film noir shot entirely from the viewpoint of its unseen protagonist searching for clues to the mystery of her own fate in the crime scene that surrounds her.

Mimi Plumb, The Golden City, published by Stanley/Barker, 2021.

Mimi Plumb, The Golden City, published by Stanley/Barker, 2021.

Mimi Plumb, The Golden City, published by Stanley/Barker, 2021.

Mimi Plumb, The Golden City, published by Stanley/Barker, 2021.

The vision offered by Genesis Báez in her 32-page booklet La Luz También Viaja is nearly as dark as Plumb’s, yet more hopeful because more keenly alert to the potential for intimate connection. It was published in 2022 in an edition of 400 by Matarile Ediciones, which is based in Brooklyn and Mexico City and describes itself as “an artist-run photo book publisher that focuses on artists who are immigrants, their children, or part of a recent diaspora.” Born in Massachusetts to Puerto Rican parents, Báez observes, “The light carving a portal in Massachusetts is the same light bouncing off a mirror shard in Puerto Rico.” This almost mystical sense of connection via the vicissitudes of light glimmers through often shadowy colour images framed, significantly enough, by pages printed black rather than white. I suspect Báez could be obsessed by Caravaggio. The image— however fragmentary (shard-like), off-centred and full of confusing reflections as it may be—is its own place, but the light that Báez announces in her title as her true subject comes to the image with the tentative and curious quality, as hesitant as it is exploratory, of a newcomer. In the central spread of the staplebound booklet, we see the legs and hands of two figures (one female, one male, though one can’t tell for sure) in a room as they carefully lift a large glass cylinder filled with water, illuminated by the light of an otherwise unseen window. Although the awkward effort to handle the heavy vessel without spilling its contents is beautifully observed, what the picture is really interested in are the strange, distorted reflections that seem to live inside the water like exotic fish—and then the patterned lights and shadows cast on the floor beneath. Yes, light travels, as the title insists, but it changes in the travelling, and likewise changes what it comes to illuminate. If that’s a metaphor for what Báez calls “the dispersion of diasporic life,” it’s a profound one, which the artist has plumbed more deeply than one might have imagined one could, in less than 20 images.

Genesis Báez, La Luz También Viaja, published by Matarile Ediciones, 2022.

Genesis Báez, La Luz También Viaja, published by Matarile Ediciones, 2022.

Genesis Báez, La Luz También Viaja, published by Matarile Ediciones, 2022.

Genesis Báez, La Luz También Viaja, published by Matarile Ediciones, 2022.

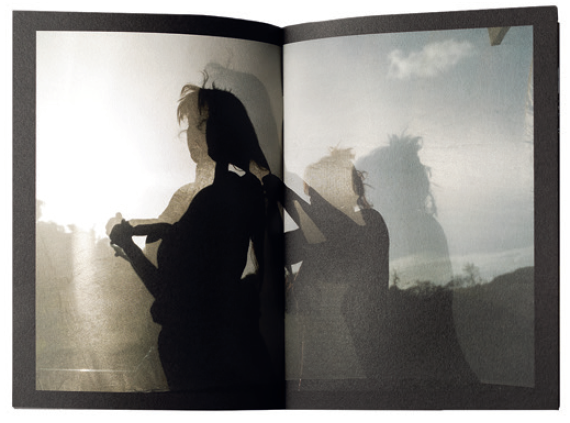

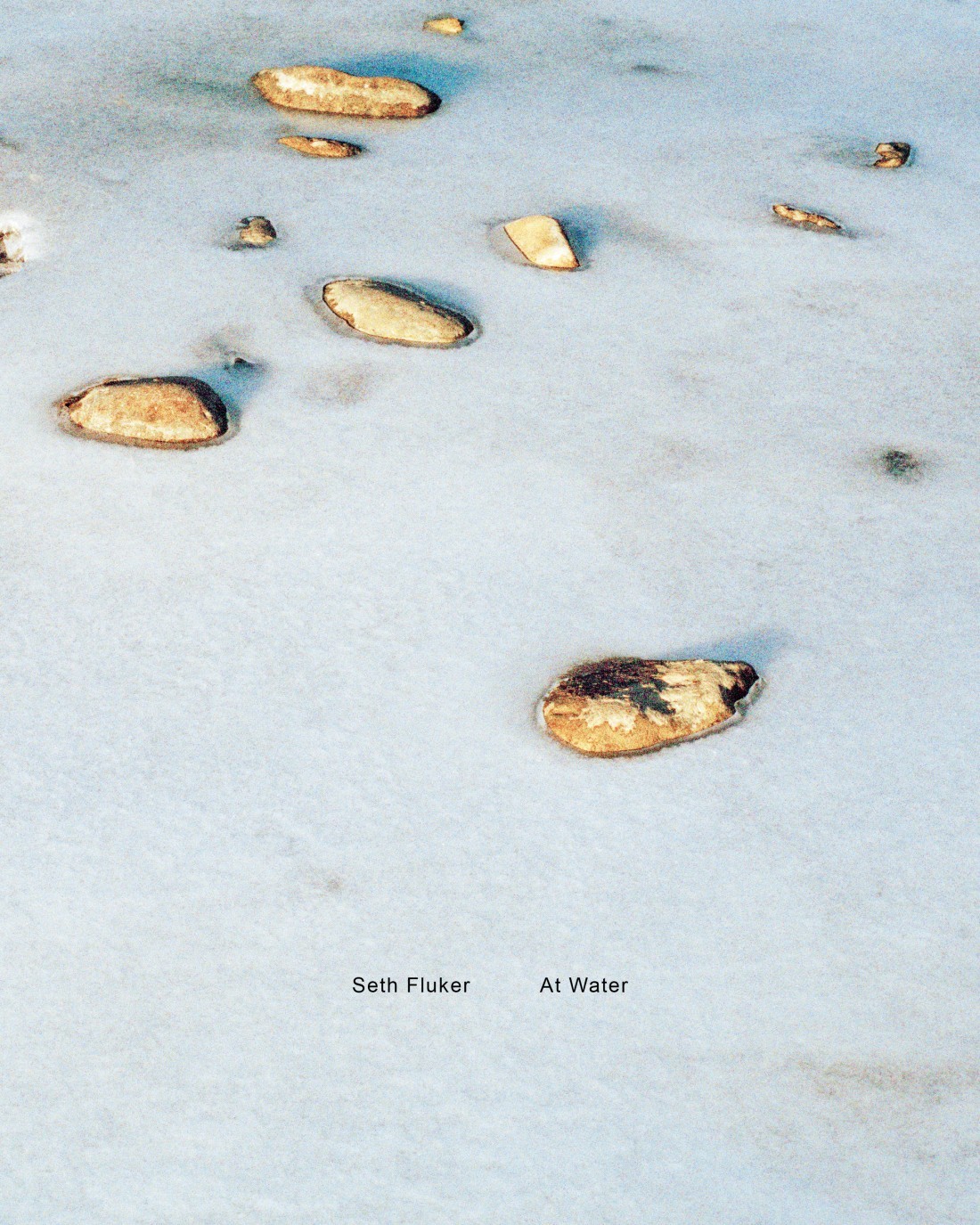

Another booklet that bears more weight than its slim profile might promise is Seth Fluker’s At Water (New York: Hassla, 2022; edition of 300). It’s his seventh publication, and among its predecessors, one notes, is a collaboration with fellow Torontonian Sheila Heti, Seth and Sheila Stayed Behind (Los Angeles: New Documents, 2015). I haven’t seen that one, but the resonant topos of staying behind seems to complement the gist of At Water, which is very much about ranging around, seeking places out—and possibly leaving others behind in doing so. It would be very straightforward to say this is landscape photography, but its 13 colour images from 10 places across Canada and one in Japan suggest an unusual angle on the notion of landscape, thanks to their focus on H2O in the form of clouds, snow and mist as much as its liquid guise. Only three of the pictures are shown as two-page spreads, and while I’ve always been slightly allergic to seeing a good photograph split across the gutter—something about which I’ve periodically had to bite my tongue in writing this column, for fear of turning my objection into a hobby horse—in this case, it’s worth it for all the detail that reads so much more vividly at a slightly larger scale. Besides, Fluker does not exactly compose his images, though in fact they turn out well composed, as amass them.

Seth Fluker, At Water, published by Hassla, 2022.

Seth Fluker, At Water, published by Hassla, 2022.

Seth Fluker, At Water, published by Hassla, 2022.

Seth Fluker, At Water, published by Hassla, 2022.

He perceives a marvellous density of information in the natural scene; and its beauty, as he shows it, is not a form imposed on the world but an emanation from within it, which the prepared eye can humbly receive. This allows, as well, for a certain quantum of mystery to emerge at times—for instance, to my eye, the way some stones emerge, glowing, from the frost in a couple of pictures at Elbow River (Sandy Beach), Calgary, and in one of the two, there is a sort of hole in the frost as if one of the stones had wandered like a photographer looking for something that would look interesting in a flat rectangle.

Is the absence of other people essential to such perception? Could be. We are so primed—neurologically as well as culturally—to fix our senses on other people that they can be a distraction when the point is to attend elsewhere than to the human; in any case, a sort of Thoreauvian solitude seems to be inherent in these pictures.

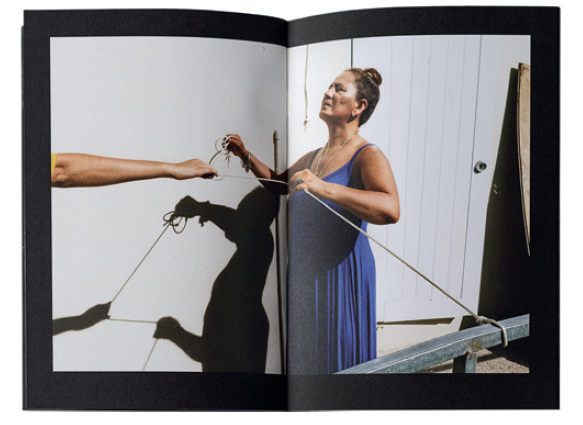

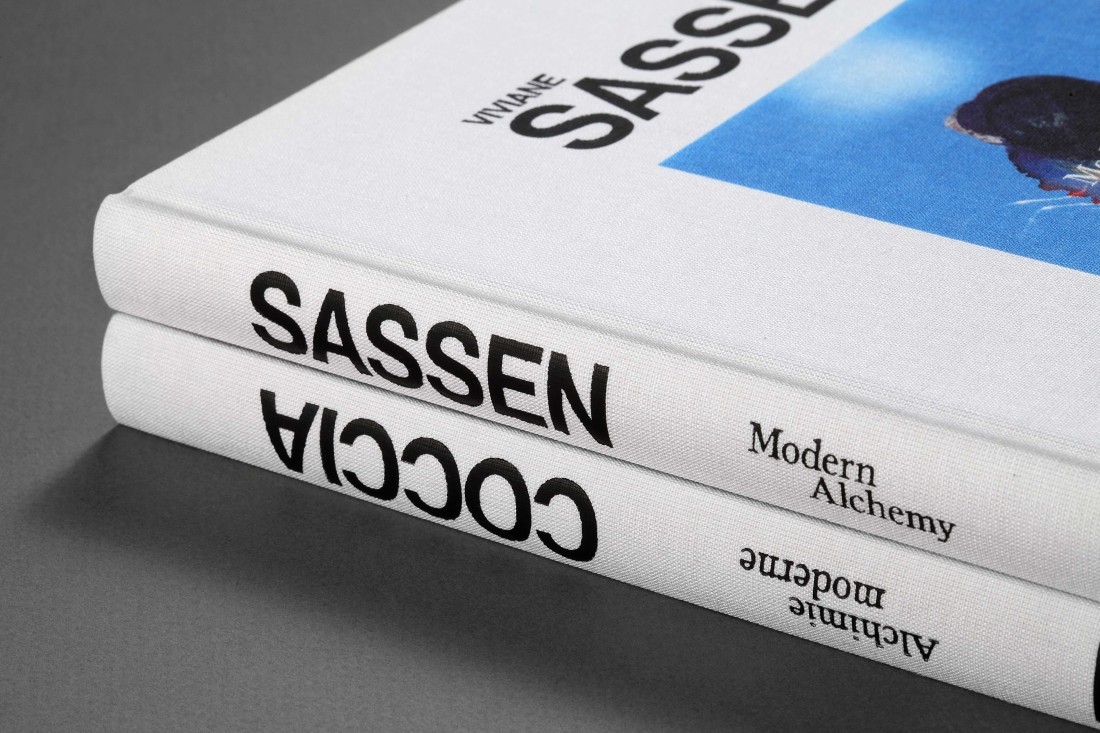

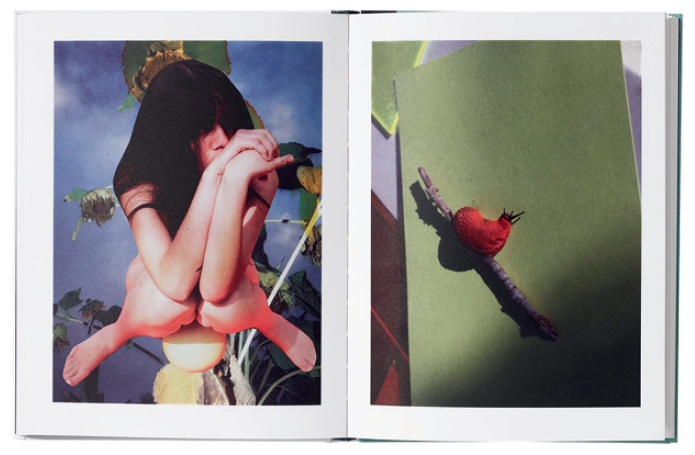

Since her first book, Flamboya (Rome: Contrasto, 2008), the Dutch photographer Viviane Sassen has been publishing at a fast clip, averaging more than one book a year. Her latest is Modern Alchemy, a collaboration with philosopher Emanuele Coccia (Paris: JBE Books, 2022), and in some mysterious way also, according to its colophon, part of a series “conceived by Mathieu Cénac and David Desrimais for Maison Perrier-Jouët”—though I did not notice anything reminiscent of champagne in the book, beyond its quality. In fact, it’s luxuriously printed. I even love the way the book smells, and maybe that’s appropriate, as Sassen’s images make me feel as though I were breathing them in through my eyes, rather than, in any ordinary sense, looking at them.

The images are collages that seem to have been treated at times with watercolour or transparent inks; chromatically lush, they affect the viewer/reader at a corporeal level before becoming an object for the rational or hermeneutic mind, so that to interpret them feels something like unravelling one’s own subjective associations and fantasies. Flowers, insects, fragmented human bodies (mostly female) and other natural or unnatural yet symbolic forms embrace, flowing in and out of each other. Even more than other work of Sassen’s that I’ve seen, they affirm her declared connection to the poetics of surrealism, according to which the image is a construct based on the “juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities”—the words are Pierre Reverdy’s, as cited by André Breton. The results are at once uncanny, seductive and disturbing. But make no mistake: a searing red, a bottomless blue, a luminous green, a subtly shaded ivory are in themselves as fascinating as a breast, a leaf, the sky, or a ladybug; the only question is, which is the vehicle for which—the object for the hue that it bears so fervidly, or, on the contrary, the hue for the object whose existence it discloses, discreetly or blatantly as the case may be?

Viviane Sassen, a collaboration with philosopher Emanuele Coccia, Modern Alchemy, published by JBE Books, 2022.

Viviane Sassen, a collaboration with philosopher Emanuele Coccia, Modern Alchemy, published by JBE Books, 2022.

Viviane Sassen, a collaboration with philosopher Emanuele Coccia, Modern Alchemy, published by JBE Books, 2022.

Viviane Sassen, a collaboration with philosopher Emanuele Coccia, Modern Alchemy, published by JBE Books, 2022.

As for Coccia’s essay, whose 12 sections are spread throughout the book, I wish he had shed more light on such themes. But while Sassen has said that her intention is “to introduce structure into the chaos—I’m crazy about chaos—of all the things I see,” Coccia is too enthusiastically rhetorical in “recognizing the material and spiritual continuity that connects all things regardless of their nature or qualities,” effacing the very distinctions that give such continuities their point. That’s unfortunate, because he clearly does comprehend Sassen’s art, which agrees with him that “living beings not only transform the world but animate it, grafting an external mind onto matter. As if the vortex between the hand and the mind that we call ‘consciousness’ could be channelled through to the external world and become part of objective reality.” And he even inadvertently makes an observation that illuminates Plumb’s feeling that she perceives certain images in her back: “We only have eyes because we can move around on our feet. It is impossible to think about an ear without thinking about the back: half of our body is lacking any kind of perceptual instrument precisely because our ears allow us to anticipate and imagine what is happening behind our backs.” Another form of synaesthesia—just as Sassen’s images give me the impression that I received them through my sense of smell, Plumb may feel that she found her best images by listening rather than looking for them. It was the literary critic Hugh Kenner who once made the sibylline observation, “The most creative way to look is to listen.” ❚

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition “Jeff Wall” at Glenstone Museum, 2021. His new collections of poetry are Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022) and Water from Another Source (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2023).