Vertigo Redux

The Green Fog, directed by Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson, and Guy Maddin

In Vertigo, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 masterpiece, and arguably the greatest film ever made, John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson, played by James Stewart, visits his old friend, the shipbuilding magnate and wife-murderer-in-waiting, Gavin Elster, and they talk about San Francisco, the city in which they both live. “You like it?” Scottie asks, and Gavin says, “Well, the things that spell San Francisco to me are disappearing fast.” In The Green Fog, the most recent collaboration between Guy Maddin and Galen and Evan Johnson, the things that spell San Francisco appear so fast and so frequently that you almost can’t keep up with them. The three Winnipeg filmmakers, who operate under the collective name Development Limited, have made a camera-less film that uses sections from 98 features and three television series, all set in or about San Francisco, and have remade Vertigo without using any shots from the original film.

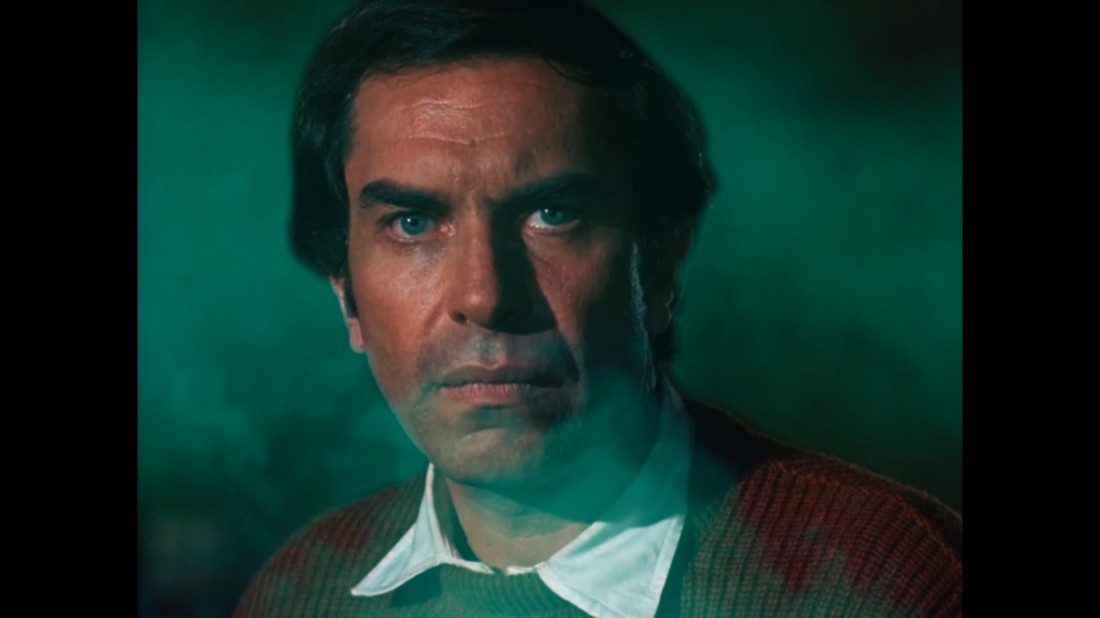

Martin Landau in ‘The Green Fog— A San Francisco Fantasia.’ 2017, Evan and Galen Johnson & Guy Maddin.

That last claim isn’t entirely true; they do include the first shot from Vertigo, the close-up image of the rung of a ladder that is about to be grasped by the man fleeing the police and Ferguson in the famous rooftop pursuit scene. The rest of their combined 63-minute-long tribute to both Hitchcock’s film and the city in which it was shot is a compilation of found footage from mostly forgettable ’70s and ’80s films and television series. What they have made from this “bottom of the barrel” trolling is an absolutely captivating, ingenious and intelligent film. Hitchcock, who was a compulsive film-watcher himself, might not like what they have done, but he would be hard-pressed not to admire it. (The film, under the title The Green Fog—A San Francisco Fantasia, received its world premiere in San Francisco on April 16, 2017, with live music composed by Jacob Garchik and performed by the Kronos Quartet.)

The film was a commission to celebrate the San Francisco International Film Festival’s 60th anniversary, and what the festival director wanted was a film that would pay tribute to that legendary city. Maddin and the Johnson Brothers began thinking about city symphony films, like Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), or Jean Vigo’s À propos de nice (1930). With that idea in mind, they started screening films about San Francisco gathered from various databases in December of last year. After looking at 40 or 50 films they noticed every one had scenes that were reminiscent of Vertigo. The city symphony idea morphed into a film that took Hitchcock’s story of vertiginous fear and obsession and reimagined it through existing film and television scenes. Once they decided that Vertigo was the form, the process of gathering the content was quick, what Galen Johnson describes as “a month of watching and a month of making.” What also became clear was that they didn’t want to create a scene-by-scene remake of Vertigo, the kind of thing Gus Van Sant had done with Psycho. “Rather than a slavish remake,” Maddin says, “our approach was that wherever possible we would withhold what Hitchcock shows and show what Hitchcock withholds. It was a way of presenting the same trajectory but by constantly switching the point of view, by as much as 180 degrees.”

You can see evidence of that switching in the Prologue, which encapsulates the way the film operates. The first three minutes employ shots taken from various films of people watching and listening for news, and then sets a foggy mood by showing a man running through the wet, green streets of San Francisco. It is a sequence from The Love Bug, the 1963 Disney comedy about an anthropomorphic Volkswagen. The original scene is all wrong in content and perfect in tone. It is followed by seven shots of the ladder rung, and the seventh time it is grasped by a pair of hands. This lift from Vertigo leads to 26 separate cuts of men running on rooftops, until we finally get to a figure teetering on the edge of falling, The Green Fog’s version of the event that underlines Scottie’s vertigo. In this showing he is played by Vincent Price, from Confessions of an Opium Eater, the 1962 film about San Francisco’s druggy underworld in the 1890s.

The opening shot of the Prologue is taken from an episode of Macmillan and Wife, the ’70s television series starring Rock Hudson as a detective who spends much of his time trying to solve crimes by looking at monitors. (This television series, as well as Hotel and The Streets of San Francisco, was the source for many of the details in their reconstruction.) Hudson ends up playing two roles; he is sometimes Scottie and oftentimes a surrogate for the filmmakers, doing what Maddin and the Johnson Brothers were themselves preoccupied with: looking for answers while screening moving images. At one point Macmillan is asked by his phlegmatic partner, Sergeant Enright, “What are we looking for, sir?” and his response is, “I don’t know, but at this point I’ll take anything.”

Maddin and the Johnsons are more discriminating. They divided Vertigo into its indispensable scenes—the opening rooftop pursuit, the restaurant where Scottie first sees Madelaine, the car scene where he follows her through the city’s hilly streets, the museum scene, the rescue and subsequent awakening in Scottie’s apartment, and the makeover sequence—and then they set about to find corresponding scenes from their San Francisco repertoire.

Their finds are serendipitous. For the museum scene they use a sequence from Born to Be Bad, a trashy 1950 noir directed by Nicholas Ray, in which Mel Ferrer munches on a biscuit while moving back and forth between two identical young girls, who are themselves looking at paintings. It absurdly reiterates the male gaze while it captures the idea of the female double represented by Madelaine and Judy, in this case embodied in a pair of innocent girls. The rescue-and-awakening combination moves from a number of watery shots, including a pair of scuba divers rising to the surface, until it climaxes in a black and white shot of Leatrice Joy, flimsily clad, who emerges from the water and ends up wild-eyed, dishevelled and a bit confused in a bed. It is a scne from Cecil B DeMille’s first version of The Ten Commandments, a silent film from 1923.

But the Johnsons and Maddin also wanted the scenes they chose to have what Evan calls “intertextual resonances that reveal the contradictions in Vertigo”; these scenes perform double duty by both telling the story and critiquing it at the same time. Their version of the makeover sequence works brilliantly in this respect. Scottie’s obsession to turn Judy Barton, a salesgirl from Salina, Kansas, into a copy of Madelaine, with whom he is obsessed and for whose death he feels responsible, is one of Vertigo’s most notorious ideas. It is the culmination of the film’s problematic male gaze. The Green Fog includes a number of variations on the makeover, but the most amusing is taken from Zodiac Killer, a grindhouse thriller made in 1971 in which Grover, a bald truck driver, prepares for a date by putting on cologne, a shiny suit and maybe the worst toupee in the history of cinema. The fact that he is a character and a suspect in a film about a serial killer in the Bay Area is unimportant to his repurposing in The Green Fog.

Most of the mischief Maddin and the Johnsons build into their version of Vertigo circulates around ideas of power and sexual control. Famously, Hitchcock’s film fails the Bechdel Test, a standard that requires a film to include at least one scene in which two women have a conversation where they talk about something other than a man. No such scene exists in Vertigo, so The Green Fog inserts its own. Much of the dialogue from the borrowed scenes is removed, which leaves only nods, raised eyebrows and knowing looks that insinuate meanings that were never part of the original films. “Once you remove the dialogue,” Galen says, “then those scenes become erotically charged.” The Johnsons’ solution to the Bechdel problem shows two women sitting in a bar, and one of them says to the other, “I always go to the museum on Saturday.” It is a tidy link to Vertigo, but what is more intriguing is that one of the women wears a rakish hat and looks like she’s in drag. In the background the other patrons are women, and as a viewer you imagine the scene is set in a lesbian bar. There is a similar mischievous addition in one of the surplus dinners included in The Green Fog. It is a scene from an episode of The Streets of San Francisco in which a blue-eyed preppie son sits uncomfortably at the dinner table with his father and an older black man. With the conversation edited out, the encounter assumes a loaded homoerotic weight. The effect is to redirect the sexual dynamic of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. This particular scene doesn’t directly relate to Vertigo, but it suggests an alternative possibility for a film that concentrates on the manipulations of heterosexual love. There is even a high heel on a man’s naked groin dropped in from Jade, the 1995 erotic thriller directed by William Friedkin. The Green Fog wants to open up Hitchcock’s sexual vocabulary.

There is a lot to look at in the film. One of the central visual tropes of The Green Fog is men looking at women, but no less persistent is the process of men looking admiringly at themselves. The best example of this dimension of the self-loving male gaze comes in another sequence that moves from Michael Douglas getting out of bed in Basic Instinct, leaving Sharon Stone in the rumpled sheets, and walking to the bathroom. We see his butt, which becomes a male posterior from an Eadweard Muybridge locomotion film, and the gaits are perfectly matched. The Muybridge appears on a monitor in a scene from The Streets of San Francisco, in which Michael Douglas says to Karl Malden, who plays a character named Mike Stone (no relation to Sharon), “Boy, you look good, Mike. You ever thought about going into show biz?” It’s a virtuoso conflation—the consummate expression of smug male posterior narcissism—and who better to articulate it than Michael Douglas, the self-confessed sexual addict?

The other major addition The Green Fog makes to Vertigo’s scenography is the earthquake and fire for which San Francisco is famous. What was needed was “a big bold climax,” so Maddin and the Johnsons intercut a series of intense arguments between men and women (which stand in for Scottie’s dragging Judy to the church where the criminal deception took place) with an equal number of earthquake and fire scenes where chandeliers fall, walls crumble and the earth opens up. They even include a sequence where the tentacles of the giant, radioactive octopus in It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) terrorize the inhabitants of the city before it is finally—and rather easily—driven back to the water by a couple of soldiers with a flame thrower. The entire earthquake seems to have been caused when Macmillan, being held hostage by some criminal in a screening room, tosses his cigarette into a wastebasket full of film and the whole thing ignites. The image on the monitor that has distracted the bad guy so Macmillan can effect his necessary pyromania is the giant octopus. Earlier in the film the projector breaks down in yet another screening room, and Macmillan says, “That’s the trouble with that old film.” It comes at the 14-minute mark and it is the first full sentence spoken in The Green Fog. The ultimate subject of a film about a film is, inescapably, film. That recognition generates its own vertiginous obsession.

To help his obsessive search for understanding Madelaine’s mysterious confusion, Scottie asks Midge, “Who do you know that’s an authority on San Francisco history?” Were he to ask that question today, the inimitable Midge would have to add a new trio of experts on the filmy lore of the city to Professor Saunders over in Berkeley and Pop Liebl at the Argosy Book Shop. “Well, there are three of them, and they know the small stuff as well as all the juicy stories,” she would say. “Their names are Evan and Galen Johnson and Guy Maddin, and they’re out there somewhere in the green fog.” ❚