Tracing meaning from Scratch

An interview with Rosa Barba

Rosa Barba doesn’t settle. The Italian-born, Berlin-based artist is constantly shifting her way of thinking about the art she is making. She is primarily a filmmaker and sculptor, and her inclination is to see how much expansive pressure she can put on the formal confinements of the two disciplines. “I am interested in finding the boundaries and connections and intersections between things,” she says in the following interview. “The way I work with film is that I find where these forms come together and then I try to open up the in-between spaces.”

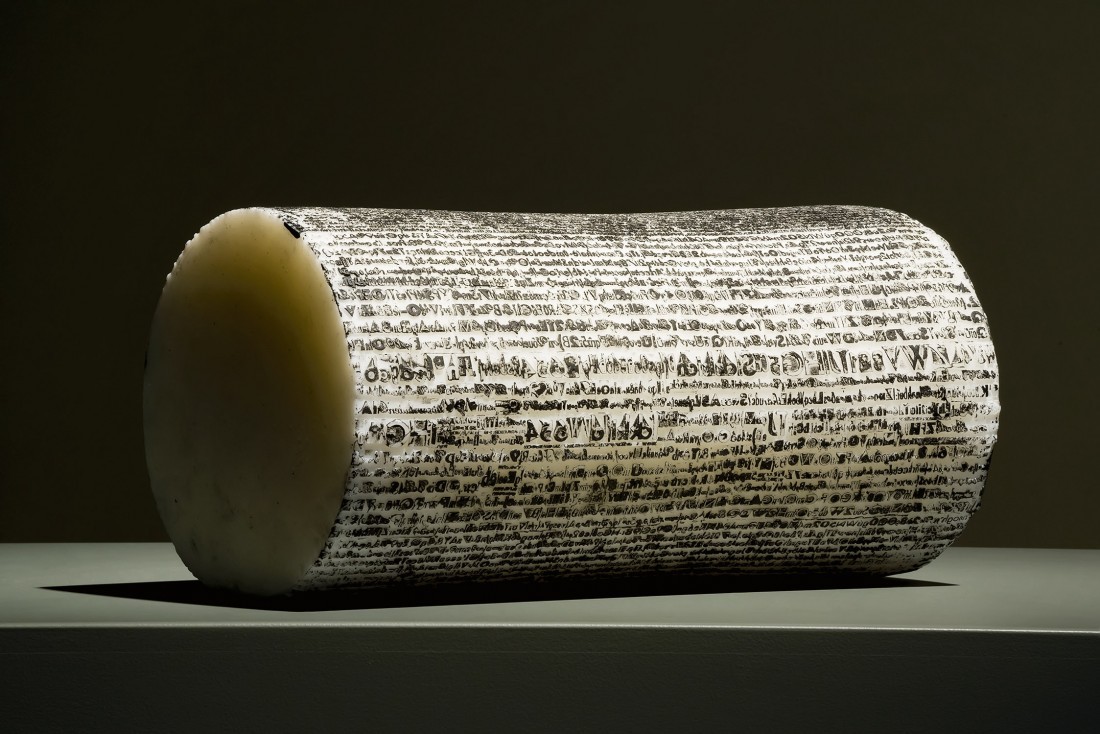

In Barba’s made world, everything crosses over into everything else. In “Send Me Sky” (curated by Sandra Guimarães, the exhibition ran at the Remai Modern in Saskatoon from September 28, 2018, to January 13, 2019), she included a number of different apparatuses that projected images and then altered the way they were received. She regards the components of cinema—the projector, the sound, the lights, the language and text—as protagonists, and she plays with perception by obscuring and augmenting any and all of them. In this complicated engagement, what is common to all her work is what she called in 2012 “the theme of instability.” One reading of that condition is embodied in sculptures like Isolation of Information (roller) from 2015 and Language Infinity Sphere, 2018. The latter is a steel ball with an infinite number of lead letters and numbers that, when rolled on a surface, produces an image where the surfeit of written language provides an absence of readable text. The trace of letters it leaves is a cosmology of indecipherability.

Rosa Barba, Isolation of Information (roller), 2015, linoleum print ink on moulded wax, 28 x 55 cm. Photo: Blaine Campbell. © Rosa Barba.

Barba has remarked that she wants her exhibitions “to be experienced like an orchestra with different players who play different music, engage in different discussions.” In this spirit she curated “The Hidden Conference: About the Shelf and Mantel,” 2010, an exhibition of objects from the collection of the Reina Sofia in Madrid in which the paintings, sculptures and videos spoke to one another in an ongoing and anachronistic conversation. The pieces had been produced in different periods, and so her organized conference provided these objects an opportunity to talk to one another, and to us, without the limiting contexts of historical time.

What is important to realize is that in all her installations, Barba never moves towards spectacle. Her individual works and their interactions are actually quite discreet and even elegant. (Her lead infinity sphere has the compact beauty of a Roni Horn sculpture and her projectors have the kinetic beauty of Rebecca Horn’s exquisite machines.) In place of spectacle, viewers get something closer to speculation as they find themselves wondering at the connections between things. In Barba’s hands, these connections are nuanced. Not surprisingly, she named a film shot in Alexander Calder’s studio in Roxbury, Connecticut, Enigmatic Whisper, 2017. The location and the motivation were ideal. Calder called his sculptures “mobiles”; as objects, they were rooted, and moveable, just as she sees film as a medium that is simultaneously mobile and sculptural. Barba is always in at least two aesthetic places at once. (Since 2004, she has produced an artist’s book to accompany her exhibitions under the series title “Printed Cinema.”) One of the most successful examples of this aesthetic double occupancy is her ongoing “White Museum” series, in which she literally projects the museum outside, and, in the process, turns the aspect of landscape she illuminates into a character in a moving film story. (In Saskatoon the white-light projection framed a section of the South Saskatchewan River.)

Barba’s understanding of how meaning is gathered and expressed is one of her central questions. She says she operates less by getting rid of all meaning than by “carving out one meaning that I want to enhance,” and from that focus she creates additional meanings to go along with her initial enhancement. The process is one of fragmenting and dismantling and then using those pieces to build new layers of meaning.

Language Infinity Sphere (prints), 2018, linoleum print ink on canvas, 155 x 210 cm each. Photo: Blaine Campbell. © Rosa Barba.

There is nothing in this attitude towards knowledge that is cynical or negative. Barba’s acceptance of how much there is to know is a kind of limitless freedom, galactic in its scope. In The Color Out of Space, 2015, another of her sculptural films, a miscellany of voices presents a view of the universe that is equally scientific and poetic, and both end up being richly inconclusive. She recognizes that we know nothing about 96% of the cosmos. “When I found out we only know 4% it was a great and useful grounding,” she says. Rather than seeing the disproportionate percentage as a problem, she accepts it as a measure of how much knowledge is available to our imaginations. That gap is the white screen at which Rosa Barba continues to project the substance and shadow of her compelling art.

The following interview was conducted at the Remai Modern in Saskatoon on September 28, 2018.

BORDER CROSSINGS: Tell me about your entry into the art of cinema. Didn’t you work as a projectionist when you were a student in Cologne?

ROSA BARBA: Yes. I was still in school and I wanted to get a job that interested me more than working in a bar. I was going to the cinema and I saw an ad that they were hiring projectionists, and along with the job was the offer of a minor degree of some kind. I put my name in and they called me. So at the age of 17, I already had a paper that said I could work as a projectionist. I took that with me when I went to study in Cologne and I was able to find a job. It was at an arthouse cinema and sometimes there were only three people watching the film. There would be six reels per film and I often mixed them up, so the film was rarely shown chronologically but no one in the audience seemed to mind. At the time I was not completely sure that I was going to go on in cinema. I was interested in theatre and I was quite serious about modern dance. I didn’t formally study dance until I was 19 but I had been performing from the time I was 14.

In 1915 Marinetti published his famous manifesto on film where he says film is a new and more agile artform. Do you share either of those views?

Yes. I was looking for a field where I could have the most freedom and I decided that film was the place where I could bring in more of what interested me, the movement and the performance and the sound.

When you discuss cinema you often shift from cinema to something else. So you’ll talk about one of your installations as being more like sculpture, or another one will be “a choreography of a musical score”; and you’ll refer to your colour clocks as “coloured paintings.” It seems natural that you would move into an expanded form of cinema.

Yes. I am interested in always finding the boundaries and connections and intersections between things. The way I work with film is that I find where these forms come together and then I try to open up the in-between spaces.

So rather than articulating the limitations of the form, you want to operate in the interstices?

Well, it is by articulating the limitations that I’m able to open up a new space.

Installation view, “Send Me Sky,” 2018, Remai Modern, Saskatoon. Photo: Blaine Campbell. © Rosa Barba.

One of the things about the apparatus of cinema—the projector, the screen, the sound system—is that it is already sculptural. So in some sense you take advantage of the sculptural inheritance of these objects.

Yes, and that recognition was helped by working in a projection booth and already seeing that as a sculptural happening. There were often different machines lined up, and you had to jump from one to the other. It’s not like that anymore but that was a very performative setting.

Other critics have talked about your doing an “archaeology of cinema,” and you’ve referred to yourself as someone who deconstructs cinema. How does each of those categories make sense of the way you operate as a cinema artist?

I think the way I work with the material is probably more about deconstruction and the archaeology is in the content of the possibility of what cinema can capture, in the inscriptions of society and how we live, and how you can observe this through the camera. Like the White Museum (South Saskatchewan River) project here: by putting light on a specific landscape near the river, I’m able to tell a part of the story of the river and to reveal an aspect of its historical potential. Using light to reveal these dimensions is another sort of archaeology.

It is interesting that while the White Museum started out in a very specific location, it has now become a transportable site-specific piece that you can move around the world.

The piece breaks out of the museum and extends the exhibition to the outside. but, of course, the outside needs to offer something I want to connect to. When I came here to do a site visit, I learned about the South Saskatchewan River, and in looking into the exhibition spaces and going out and having this incredible view onto the river, it seemed to be calling for it. That doesn’t happen in every space that I show in.

One critic has said that you evacuate meaning from cinema, so you’re involved in a kind of emptying out.

Maybe I’m not getting rid of all the meaning but carving out one meaning that I want to enhance. Then I create other meanings to go along with it. In the beginning when I was watching films, there was too much information and there wasn’t any space left where you could start to think for yourself. Everything was already thought for you. So the question became, how do you find your own thinking space? Right now we seem to be told that we shouldn’t have these spaces anymore, and in part it directed my idea of breaking the status quo of cinema. I wanted to find cinematic spaces where that could happen and, beyond cinema, to use art to create new thinking spaces and platforms where we can act and experiment.

There is something inherently contradictory when you consider film as sculpture because film moves and is immaterial and sculpture is static and substantial. One deals with time, the other deals with space. In your thinking about cinema, are you playing with these contradictions and are there ways you have found to exploit that doubleness?

Yes, there are some sculptural works that toy with certain given ideas about what celluloid should do and what the machine should do. There’s a ludic mentality in turning things around, but then there are also other objects or sculptures, like Western Round Table (2007), where I’m trying to make an image of an historical moment. It deals with a meeting and discussion about modern art in 1949 in the Mojave Desert. How do we give an image to something that we didn’t participate in and don’t know what was spoken about? So in this case it was more a question of giving form to an historical moment rather than creating a sculpture.

Installation view, “Send Me Sky,” 2018, Remai Modern, Saskatoon. Photo: Blaine Campbell. © Rosa Barba.

Is the inescapable conclusion we come to in looking at your work that there are no pure media, that nothing is unmediated, and all media are compromised? So then you have to find strategies for subverting them?

And that can be as simple as stopping what a machine or the materials should regularly do. In a work like Stating the Real Sublime, the projector—the machine itself—doesn’t have much of a function anymore and the celluloid takes over the narrative and makes it useless. I see these works as an experimental understanding of how to release these new meanings.

What’s your fascination with the machinery? You use old technologies, which look different and have different sounds. The sound of the projector itself is mesmerizing. Are the machines as seductive to you as they seem to be to viewers?

They are. From the beginning I didn’t see the need for the objects to be hidden. I mean, they are the ones doing the performing so they should be part of this orchestration. I have experimented with that idea. When I did this live piece for Performa at the Anthology Film Archives in New York, I had several sculptural works in the audience sitting next to people. Then I involved the projector in the booth by leaving the sound open. You wouldn’t normally hear what is happening in the booth and suddenly you’re hearing the machine turning up and arriving at the right speed. The machine can help the audience play with the possibility of activating and embarking.

I’m interested in your use of narrative. In Outwardly from the Earth’s Centre (2007), you invent a story about a society living on a piece of land that is in danger of disappearing. Is that the way your narrative works, as an invention that has to address both place and experience?

Yes. There is always something that triggers my imagination and then I start to dig into that by talking to people and going into archives. I had heard about this uninhabited Swedish island called Gotska Sandön in the Baltic Sea that was drifting. I began to wonder, what means could we use to fix the island? The first idea was to use ropes, and in the archives I found images where people tried to do exactly that. You can’t plan things like that, but what often happens is that in the research you discover places where fact and fiction overlap.

…to continue reading the interview with Rosa Barba, order a copy of Issue #149 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!