Tough Love

An Interview with Kelly Mark

Kelly Mark, I Love Love Songs … But Angry Music Makes Me Happy, 2017, single-channel video, silent, 6 minutes with reverse loop. All images courtesy the artist and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto.

Kelly Mark works hard as the self-employed worker Kelly Mark. For over two decades the Toronto-based artist has been making videos, drawings, sculptures, text pieces and performances that have earned her a reputation as one of Canada’s most important conceptual artists. Labelled favourably by critics as “a working-class conceptualist,” she has been attracted to ideas from her earliest encounter with art. In the following interview, she remembers her first day at the Dundas Valley School of Art in Hamilton, Ontario, where she recognized that being an artist had nothing to do with how well you painted. “It was about adults sitting around talking about ideas and I had never experienced that in my life. So by the end of the first week I knew that was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.” There is something both poignant and profound in her early recognition, and it has turned into a lifelong conviction.

Mark has remarked on many occasions that an inherited work ethic has governed her art production. If you can do one thing, she readily admits, then you can as easily do 30, the number that seems to be her numerical touchstone. While it is true that she believes in hard work, it is important to realize that she believes no less passionately in the catalytic role that the imagination plays in artistic production. Let’s call her “a conceptual labourerist,” wearing her workingclass heart on her rolled-up sleeves for anyone to peck at.

Part of what makes her work so likeable is the evidence it provides about the kind of person who would produce it in the first place. Mark is an artist who is not short on personality, and she has cultivated a no-frills, baseball-capped, harddrinking and -smoking, tough-girl image that is both personal and persona. She is that person at the same time that she knows she is performing that person.

She is prone to colourful language. In Litany, 2001, a drawing etched on aluminum foil made in an edition of only two, she wrote and then framed, in reverse, every swear word and combination of swear words she could think of; in Fuck Yeah (Portrait of the Artist as a Curmudgeon), a grumpy manifesto from 2016, she combines her expressive language with her favourite character trait, tempering the surliness with as much humour as she can manufacture.

Smoke Buddies, 2017, two video stills, single-channel video, silent, 11 minutes.

Mark is extremely funny, and she delivers her punchlines with economy and sometimes with a left hook. Her text-based pieces trace an alltoo- human toggling between wished-for selfimprovement and a recognition of abject failure, so nothing comes of the “I really shoulds,” any more than a resolution can emerge from the Everything / Nothing exchange: “EVERYTHING has a way of working itself out / NOTHING good can come from this” is a psychological end game. There are ways out, though. In The Trade Off, 2016, a cross-stitched drawing on linen, she writes in upper-case letters how to accommodate the aging process: THE TRADE OFF / OF GETTING OLD / IS THAT TAKING / DRUGS AINT FUN / ANYMORE BUT / AT LEAST ITS / TAX DEDUCTIBLE.

In Mark’s lexicon, “but” is a very big word. It’s the hinge that draws attention to the intelligent skepticism that runs throughout her practice. Her binary thinking is too subtle to be dialectical; it slips around the work like axle grease on the cog of her intelligence. There are times when she shifts gears and moves into absurdity; in 2008 she made billboard advertisements and promotional photographs for a band that didn’t exist; just as she had organized a public demonstration outside an art gallery for no issue at all, urging the 30 protestors who carried empty placards to chant the slogan “What do we want … NOTHING, When do we want it … NOW” for two and a half hours.

It was this empty form in Demonstration, 2003, that occasioned The Power Plant to invite her to stage an intervention at the Power Ball gala. In Public Performance, 2010, she hired three pairs of actors to engage in noisy couple fights, which confronted the pricey ticket buyers when they arrived at the fundraiser. They weren’t in on the performance but they most assuredly were in it. Mark’s sense of humour can be like the joke that goes, “It was so funny, I laughed my head off. Plop.”

She can also be goofy. In Sniff, 1999, a seven and a half-minute video made with her cat, Roonie, she plays what she calls “the sniff and pokey game.” The game involves her introducing to her supine cat a series of objects, and waiting for his reaction. The truth is, Roonie should have been given the Acatemy Award for Best Animal Performance in a Human Video; the range of his reactions runs from disdainful indifference to catnip-induced, consuming frenzy. (The video, which is on Mark’s excellent website, is hilarious.)

She is, herself, a skilful performer. In 108 Leyton Ave, a 10-minute-long, single-channel, splitscreen video made in 2014, she and her doubled self play solitaire and exchange a series of consecutive “Everything” and “Nothing” aphorisms, epigraphs and clichés. By the time her right-hand self moves out of frame, leaving her left-hand self playing an even more lonely form of solitaire, they will have given us a whole lifetime’s worth of hope, bitterness, longing and depression. She is adept at capturing what she describes in her artist’s statement as “differing shades of pathos and humour,” and this video embodies that frame and pretty well everything in between. Like everything Mark does, 108 Leyton Ave is carefully detailed (an image of her iconic kissing television screens hangs on the wall behind them) and disguises the prodigious amount of planning and execution that went into its making. In her working schedule, she always puts in overtime.

Everything is Interesting, 2011, neon and transformers, 40 x 3 inches. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Her most recent work seems to be punching a different time clock. While only 51, she is in a memento mori frame of mind. In 2017 she assigned that name to a bronze ashtray with a crumpled cigarette at its centre (a work that actually deserves the description “tabletop sculpture”). It is gorgeous, another example, along with Smoke Buddies, of her ability to take bad habits and turn them into exceptional art. And the dry humour persists. Her Strategy for Immortality, 2016, another cross-stitched drawing on linen, reads, “I ADDED DYING / TO MY LISTS / OF THINGS TO DO / THAT WAY / ILL PROBABLY / JUST NEVER GET / AROUND TO IT.”

But there is something about this recent turn to her own past that feels different. There is much to work back into. In Trying to Remember, Sometimes Wishing I Could Forget, 1996/2016, the twodecade- long gap in the dating is telling. Her first video, made in 1996 and called 33 Minute Stare, is now sharing a split screen with her newest video, in which she is trying to remember all the things she has forgotten. Along with the worry of not remembering comes the regret when you do.

It isn’t obvious where Mark’s memorial work will take her. But what is clear is the commitment she made 20 years ago to how ideas work in manufacturing art, and that is as organized as it ever was. Kelly continues, as she always has done, to find ways to make her mark.

The following interview was conducted in Toronto on January 20, 2018.

BORDER CROSSINGS: Give me a sense of what your life was like, growing up as a child.

KELLY MARK: Small town. I had brothers and sisters but they were older. It’s why I’m kind of a hermit and single because I grew up learning to play on my own. I used to go fishing on my own, too. I never took art in school.

So there wasn’t any art around the house?

No. When I did go to Dundas Valley School of Art, I didn’t know who Henry Moore was, or Picasso, or anything. My dad had grade eight; my mom had grade seven. No books in the house. None of the family ever went to post-secondary. So when I graduated from high school, I was expected to get a job. University was for smart rich kids. The only thing I did that had any relation to art was doodling on friends’ jean jackets and on Bristol boards with a pen and Magic Marker. I would hang out with friends and draw on their arms when we were drinking.

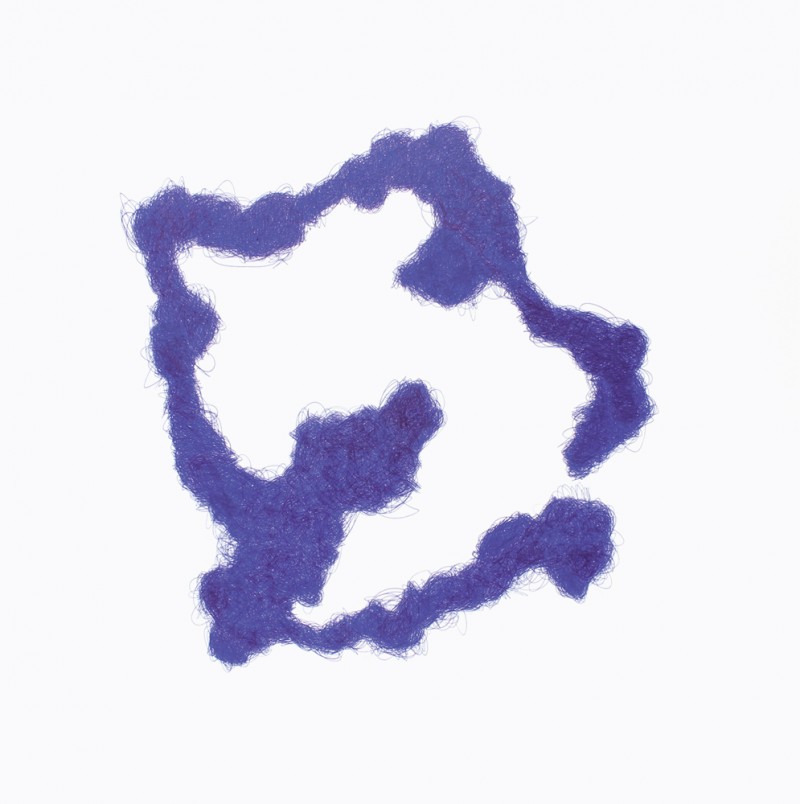

Fucking Die Already, 2017, ballpoint pen on archival matte board, 24 x 24 inches.

But you never thought of that as art?

No. After high school I worked at every shitty job imaginable. I spent six or seven years working the night shift at Mac’s Milk, getting robbed. I was living in Hamilton with some friends from high school and one day one of them came home, put the Dundas Valley School of Art application on the fridge and said, “You should go to art school.” I don’t remember why I went down there but I did. The place looked like an art school with wooden floors and windows you had to hold up with bricks. I showed them my little doodles and a week later they accepted me. I remember the first day of school clearly. I was really scared and nervous because I wasn’t smart and I didn’t have any skills. At Dundas there were always a lot of first-year students, there were second-year students, and sometimes a couple of third-year students who wanted to stick around and pay tuition. I remember the third-year students’ being really cool, wearing jackets and smoking in class. It totally felt like I was in grade nine. This was probably how they started every term, but all the first-years were taken up to the loft to do life drawing with a naked male model. I was dying and I remember thinking, “I can’t draw, what am I doing here?” I knew I was leaving as soon as there was a break. But before we were allowed to go out for a smoke, they had us walk around and look at all the drawings, and it turned out everybody sucked. It was obviously a big bonding moment, right? After a couple of days I realized it wasn’t about skills. It was adults sitting around talking about ideas, and I had never experienced that in my life. That just didn’t happen in my family. So by the end of the first week I knew that was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I didn’t know about an art career, or what that meant, or what a BFA was or anything. I knew I just wanted to sit around and talk about stuff.

What’s interesting is that the lean towards the conceptual, towards the idea of art rather more than the object of art, was present right from the start.

Yes. I was also lucky in a lot of ways. Because my dad worked in a steel mill and my mom worked at Canadian Tire, I got only a quarter of the student loans I applied for, and since my parents couldn’t and wouldn’t help out, I didn’t have the money to pay my tuition. I remember going back to school and crying, and one of my friends told the director, and they ended up giving me free tuition for two years. I had to empty the garbage and sweep up after class, and in the summer I’d paint walls and answer the phone for the secretaries at lunch.

Were you learning quickly?

Yeah. At Dundas they stopped giving me assignments halfway through the third year because I’d do 30 versions of what they had assigned. Then, because I was the custodian, I had a key to the place, so I’d work in my studio at night on my own. They loved me because of my work ethic. One funny thing was that it was a painting school and they had no sculpture facilities or darkrooms or anything like that. They had a table saw in the basement. They also said that my paintings were very physical and that I couldn’t paint worth shit, so when they gave assignments they told me to do them in 3D. I was like the dumb sculptor who had to do it in 3D.

Then you went to NSCAD in 1991.

Yes. I was very lucky there, too, because it was during the glory days. I worked mostly with Gerry Ferguson. He let me do whatever I wanted and he graded me on it. I only ever took two classes at NSCAD. One was welding because I wanted to hang out in the welding shop. And then I took a drawing class with Michael Fernandez because I thought I should improve my drawing skills, and, of course, because it was Michael Fernandez, we spent the whole semester drawing how the inside of our body felt. So I didn’t learn how to draw.

You have said that you never deal with grand concepts but with small moments. Did you quickly develop an attitude toward making art where you determined that you weren’t going for the big gesture?

A lot of it was by making mistakes. You learn by making mistakes. I had been making some figurative things in sculpture, and when I started working with Gerry, he told me to get rid of the form and concentrate on the process. I liked the aspect of the grid and I liked repetition, so I found a fireplace grate, bought a box of nails with big heads on them and just dropped them into a grid. I ended up making 30 pieces a day. Gerry would come in and say, “Cool, see you next week.” He never really talked to me about my work for the first semester and a half. At NSCAD everything was non-representational and everything had a logic. I called it “A to Z Conceptualism”; things had to have a starting point and a finishing point. It was all measurements and row after row of Carl Andre stuff, and there was a lot of taking things apart and putting them back together. Then at some point Gerry came in and talked to me about deconstruction and the Situationists and I got into that for a whole year. I was a student and if you’re a student, your work has to be about something, right? But I realized it was bullshit and it wasn’t me. I didn’t know anything about deconstruction then and I still don’t. I remember getting in trouble one Christmas for taking apart my brother’s new LED clock radio and trying to put it back together. For me, it was about investigating materials. Art is about noticing what’s happening and not following a program that runs from A to Z. I didn’t need to throw on all this stuff that wasn’t there. That’s when art is bullshit.

Tell me about the first Knife Collection piece you did in 1995.

Fucking Die Already, 2017, ballpoint pen on archival matte board, 24 x 24 inches.

I had started waitressing right after art school because it was the only thing that I knew. I was never going to teach, never going to work in a gallery, never going to be a studio assistant for another artist. But it was totally weird going back to waitressing because my head was different. I had to do it to make money, but a lot of art came out of that. All the knives were stolen in that piece, either from restaurants or from friends’ houses. A lot of people say my work ends up looking funny, but, for me, the funny shit happened when I was making it. Working on the White Jars in 1994—it was my last piece at NSCAD—I would go into a store with a shopping list that would include lima beans and a white bra; or vice versa with Black Jars two years later, it would be axle grease, a Bible, some stockings and black chili. Everything on the counter was black but no one at the cash register ever looked down and no one ever said anything.

They might have been afraid to ask. At the same time, one idea that runs throughout the work is “work.” In 1999 you did Nine to Five, where you take a two-hour segment, put it on four monitors, do the math, and four times two adds up to one working day. Were you consciously playing with the motif of artist’s labour?

A lot of it was conscious after the fact. Early on, I was concerned that my practice seemed all over the place, and it is all over the place. It’s only after 20 years that I’ll do an artist’s talk and see what I had done. Just because I made it doesn’t mean I understood all the connections. I’ve noticed that certain things do come up: humour is always there and time is always there. And so is the working-class thing. I’m working class in the sense that I don’t read books on theory and my idea of entertainment is NFL football and not the latest movie that everyone’s talking about, but at the same time I haven’t had a job in 13 years. I guess this is my job.

The way you approach the job of making art seems to be filtered through the influence of conceptualism and minimalism.

Yes. The thing is, it’s tied to personality. Everything is labelled, right? When I moved to Toronto I got a job as a line cook, and because the place hadn’t opened the executive chef asked me to organize the storeroom. When he came back on Monday I had unpacked all the boxes and organized and separated everything—tomato-based soup products, spices, chemicals—and all the labels were facing forward. You know, rows of colanders. I’m just anal as hell. I can’t make scatter work. I’ve never made a scatter work. I make stuff, right? And it’s art if you recognize it as art; if you don’t recognize it, it’s fine. But I still make stuff. I made a full-body fun fur suit for my cat once. It’s on my website and I consider it art, but no one else does. Only about half of what I do actually becomes art.

108 Leyton Ave, 2014, video still, single-channel split-screen video with sound, 10 minutes, 13 seconds. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada.

When did you first use text in one of your works?

I think I did the refrigerator first, but I don’t remember why. It was a one-night show in an apartment, and I remember I filled the fridge with white food, white jars, and supplied the outside with an erasable marker. That’s what you do, right, you put notes on your fridge? I think that’s where I started handwritten things like “I really should lose weight,” “I really should clean out my wallet,” “I really should blah, blah, blah.” Then at the end I just put “dot dot dot”; I’ve always liked the dot dot dot. I remember I was at Dundas Valley and I wrote them all out. In a way, it’s a monument to procrastination, listing common things and selfperceived character flaws.

Were you categorizing things in your head?

No, it was stream-of-consciousness: “I really should stop shooting elastics at the cat”; “I really should take the cat to the vet”; “I really should pay back my student loan.” It jumps all over the place.

In realizing how generative text could be, did you begin to play with the aphoristic, the short statement, or statements that were parallel or contradictory? Did you realize that language was a place you could go?

I never saw it as a ‘language’ kind of thing. It’s a classic conceptual framework where you have an idea of what you want to do and then you decide what form it should take: that would be a good video; that’s a drawing; that should be a bronze sculpture. A lot of my text pieces come out of watching TV or from what other people say. I heard “resting bitch face” on TV the other day, a phrase I’d never heard, but as soon as I did, I knew exactly what it was. I have a resting bitch face. If I’m not talking and animated, people think I’m mad or depressed and they ask, “Are you okay? What’s wrong?” I get that all the time. So I want to do something with that. I don’t know if it’s going to be the title of the show, but I know it’s not a drawing and it’s not a neon sign. Sometimes I have a phrase and I don’t know what to do with it. Other times it’s absolutely obvious what I’m going to do. Like when I was in Venice hanging out with the Fastwürms and either Dai or Kim said, “Nothing is so important that it needs to be made in six-foot neon.” It stayed in my head because I had made and sold a lot of stupid neon.

Commercial Space, 2007, Glow Video Installation Series, multi-channel video installation, 15 minutes, looped, silent, CRT televisions, DVD player, RF modulator, RCA cable, coaxial cables and splitters.

You play off your character a lot. Is the Curmudgeon piece meant to be a collection of humorous self-reflections?

Humour comes into it whether I want it or not. It’s called Curmudgeon because it was about me feeling pissed off and frustrated. I had just gotten sick with diabetes; there were complications and nerve damage in my leg. I was just feeling old. When I first made the work in that show, I was angry. It was “fuck Doritos, fuck Harvey’s for changing their toppings, fuck pedestrians, no, fuck drivers, fuck cyclists, fuck pedestrians, just get the fuck out of my way,” and halfway through I realized I was running out of things. That’s when the humour came in. You just have to step back and humour’s going to be there.

I know that watching TV is an obsession. When did you realize that it could be generative, that you could actually make work out of what you spend a fair amount of time doing?

The first piece was Glow House (2000–01) but I didn’t invent the idea. There was a reason I did it on Palmerston here in Toronto. It’s a really dark street because it’s got those old lights and everyone who lives in Toronto knows that Palmerston is all apartments. One Friday night I was standing outside one of these apartment buildings with a friend and these girls walk by on their way to the bar. They look at the building and go, “I can’t believe they’re all watching the same channel.” It was perfect! So it is what it is. Other than doing it a couple of times in different houses, I never planned to make anymore glow videos. But you get talking about it, and I started to realize that different lights came from different things, commercials or the news or whatever. When the news is on there’s just this boring white light with a little bit of flicker, and at the end of a movie the whole house goes dark, whereas commercials are great because they’re really flashy. That’s when I did the series, Horror / Suspense / Romance / Porn / Kung Fu (2005). There’s no difference between Horror and Suspense. I was filming the whole movie and I realized I need only 15 minutes of the most suspenseful, the most romantic and the most gripping parts. I put Porn in only because I thought it was funny. I also liked how “Porn Kung Fu” sounded.

But nothing much happens in Porn, so there’s no change or variation in the light.

The action’s great in Suspense, but Porn is a little disappointing. But that’s how I learn things. I decided to show it, but I couldn’t tell what it was like in my studio because there’s too much shit on the walls, so I had to wait to see it in the gallery. When you first walked into the gallery, you became aware that the piece is really the whole room. And while it’s true that there’s not much happening in Porn, there is this throbbing, which gets quicker and quicker. I’m like, “This is great; the room is fucking itself.” It ended up being the best one.

Porn, 2005, Glow Video Installation Series.

Just for the record, I assume you had Brancusi in mind when you did The Kiss in 2007?

Of course. I hate art about art, but this was a no-brainer.

Tell me about REM (2007), your film marathon with bits from 170 movies. How did it get made and what was the reason for its making?

Part of it was because my bank account was seized. It was an accident but I was really depressed. At the time I was watching a lot of television and I had all these crazy fucking channels on satellite TV. Every Friday night there was one channel that played these weird old Mexican lip-synch movies. It was such crazy shit, and because I didn’t think anyone would believe what I was watching, I filmed some of it. I used some of the footage in REM. But it was months later when I had the idea of doing this piece. I went to Blockbuster Video, they existed back then, and rented a bunch of movies, put them in my DVD player, hooked up my camera and my camera shut off. I realized there was built-in copyright protection. I couldn’t copy it, so it was like, “Oh fuck, I can’t do this piece.” That’s when I thought I would copy it off television. From the start I set rules for myself, like I had to find my opening scene and my closing scene on the first night. As I went along I made a few more rules, but I had no plan about what my movie was going to be. It was funny because within half an hour I had found my opening scene. It was 10 o’clock at night and I was channel surfing, and I remember catching the opening of this movie. It is a desert highway and nothing happens for the longest time, then the sun comes up and a little bit more colour comes into it, and suddenly a VW bug comes roaring past the screen. I thought, “Wow, that’s a great opening scene.” I watched television right through until two or three in the morning. Then I was watching Desert Blue (1998), the Steve Buscemi film where he’s just walking around, and it was black and white. I thought, “Black and white is good because my opening is black and white.” And while Steve is walking around there is this beeping sound, and I can’t figure out where it’s coming from. He’s getting more and more animated and he’s swearing and I love swearing. Then at the end of the movie he bolts upright in his bed, looks at the clock and it’s 4:05 in the morning. He goes, “Holy shit,” and that was my ending scene. My whole movie became something that Steve Buscemi dreamed. I thought it was perfect. So the next day I had a plan where I couldn’t cheat. I couldn’t look online to see what movies were playing and I didn’t look at TV guides or anything. Once you’re intensely watching TV, you start to notice similarities. There are tons of things where there’s a television in the background and then the movie actually turns into what’s happening on the TV screen. That also turns up in the movie a lot.

Horror, 2005, Glow Video Installation Series.

I find Smoke Buddies (2017) one of the most seductive pieces you’ve ever done. Tell me about its making.

I actually filmed it right here. The piece began as something quite different. For some reason I started using Latin phrases and I was going to write a kind of memento mori piece. One was “Remember you have to die,” and another was something like “Die alone.” I don’t remember the exact phrase. But that was supposed to be the title for the video. Originally you saw the cigarettes in the ashtray and I had a little toothpick where I glued them together, so the smoke starts off as one stream. I kept filming it over and over and over again, because I was trying to get this certain accident to happen. At one point there’s one trail but then the ashes grow. So I tried to glue one down so it would never fall. But eventually, just because of gravity, it was going to fall and burn out. The piece was supposed to have this “We all die alone” message, where just one cigarette would continue burning at the end. I was trying forever to get that to happen, and one day I was bored and I moved the camera up. I was closing windows, trying to get the wind direction right, and I came back and when I looked through the camera, I was seeing just the cigarette smoke and it was so beautiful. Because I was having so much trouble with this shit anyway, I figured, what the fuck. But then I realized I couldn’t call it We All Die Alone. That’s when I came up with Smoke Buddies.

At times it looks like a kinetic Lalique glass sculpture, or flowing silk. Smoke Buddies is also a smart pun because the two streams of smoke become almost like lovers.

Exactly. That’s what I thought.

Why is it 11 minutes long?

That was how long it took. It wasn’t edited. There’s another one where I had it at 11:11, which I quite liked, but it just wasn’t good enough. But the ending of the one I chose was perfect, because one stream obviously dies, the other one does a little curl, and then it goes off. I shot it over and over and over. It was just trial and error, and then more trial and error.

I Suck at Math, 2017, CNC cut sanded acrylic, 47-inch diameter x .5 inches. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

I’m sitting here looking at The Kiss piece and in 108 Leyton Ave (2014), it hangs on the wall behind you and your doppelganger. Where did the idea come from for 108 Leyton Ave?

Well, it’s still fodder for work. For a while I was collecting phrases with “everything” and “nothing” in them. I’d write down in my little book whatever I could remember. Then I actively started searching for “everything / nothing” phrases. In the performance, “Everything / Nothing” had to be at the beginning of every sentence. I started alphabetically. It was supposed to be a gender-based thing. The first letter is A, so the line is “Everything a woman needs.” So “Everything a woman needs—Nothing a man won’t do”; “Everything a man likes to hear—Nothing like a woman scorned.” The next line starts with B: “Everything bad that can happen will happen—Nothing is ever so bad that it can’t get worse.” It started out being a performance between a man and a woman about everything and nothing, more like a debate. Originally there were 100 Everythings and Nothings in the performance—you need some number so I chose 100. The performance was great, but there was nothing lasting so I decided to make a video. My original plan was to get a man and a woman, but a lot of my work comes out of being lazy. I was living in Scarborough and watching TV and one night I thought maybe I could do it myself. You know, I come from the era of ’70s and ’80s television where they did split screens all the time. It was cool back then when Fonzie was talking to Fonzie. So I set the camera up that night as a test, and I realized I could do it. It ended up being a lot more involved and complicated than I had thought. I spent six months on that piece, filming every single night. I must have shot it 500 times.

It’s amazing how intense it is because your two selves are in an especially unhappy relationship. It goes through degrees of disappointment, anger, distress and sometimes care.

Yes, and then at some point I’m hitting on myself.

Did you realize how much tension you could get in the performance?

I didn’t. That’s why I was dumbfounded when it was done. I wasn’t aware all that shit about me being depressed and thinking about killing myself was creeping in. I’ve never done such a personal piece. I didn’t know until the end that all that was in there, frankly. That’s what makes the piece special. I thought it was going to be funny with me talking to myself, which is why I was playing solitaire.

There are moments where it looks like one of you is trying for some kind of reconciliation.

It’s just two old people living together. They obviously don’t love each other but they can’t live alone. That’s me, right? There are times where I’m arguing with myself. Obviously we’re dealing with some personal shit there. But everything is in moderation and nothing is in excess. There are times where something gets said and there’s a pause where it’s obvious I’m trying for a comeback. So I’m playing a game.

Memento Mori, 2017, lost wax bronze cast with liver of sulfur patina, 8-inch diameter x 1.75 inches.

The Socratic line “Everything in moderation” is a classic. Then there are quirky lines like “Everything tastes better with Miracle Whip,” which is from an advertisement I remember from my childhood. But the response to it, “Nothing tastes as sweet as what you can’t have,” adds a nice twist. Did you carefully work out the score so you could get nuanced responses?

Yes, I’d go over and review the text. I tried to stay away from famous quotes, but there are three or four in there because they were so good.

The final combination is very good but it’s pretty depressing. The response to “Everything will be worth it in the end” is “Nothing ends well, that’s why it ends.”

That’s a great ending.

How much of a difference is there between the kind of public action that happens in Demonstration (2003), the first piece you did at The Power Plant, and Public Disturbance, which is done seven years later? There were hilarious moments in the latter where a guy wearing tennis gear wanders over and both the man and the woman become verbally aggressive. You can see servers at the gala avoiding the arguing couples.

That piece worked out great. I didn’t know if I was going to come out of that with any video because the piece was a performance. I had hired three sets of actors and had them deliver lines from three movie scripts: Hurly Burly, and a bad made-for-TV movie with classic dialogue like “Hey, I’m pregnant and you’re cheating on me.” The other one was Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? All three sets of couples performed at the same three locations, but they took turns. Then on the day of the performance, the older actors told me I couldn’t film them; they were old-school ’70s ACTRA members. The other two couples were cool; young artists who just wanted to do shit and nobody cared what I did. So I couldn’t film any of the Virginia Woolf argument, even though the performances were great. I shot the opening scene outside at six o’clock, probably five takes with each couple, and I got only one that worked. It’s a relationship argument, obviously, but the subtext is where should they go to eat. The opening scene is not visually great with apartment lots in the background and shit, but I wanted the fight happening when the rich people who paid $10,000 for their ticket showed up.

Still Life #3, 2009, graphite drawing series, 8B graphite pencils on wood and matte spray varnish, 13.75 x 18 x 33 inches.

So nobody coming into the gala knew what was going on? As far as those attendees were concerned, they were encountering an actual couple having a ferocious argument.

That was what I wanted. And then at eight o’clock we moved inside. Most of the rich people were leaving but all the artists hadn’t shown up yet. So it was just a lot of waiters walking around with music in the background. I didn’t realize until after that the actors were drinking the whole time, so as the evening wore on, they were getting drunker. At six o’clock, you’re going to have a normal argument. At three in the morning, when you’re hammered, you fuck up. Half of the guy’s lines aren’t right and he starts swearing more. They’re doing the dialogue from memory and that’s when the tennis guy comes in and they both tell him to fuck off. At that point, they’re both hammered.

You have that optimistic neon piece that declares everything is interesting (2003). That seems to be the way you approach the world.

That was another thing that came through somebody else. I was playing pool with a curator and I’m not a very good pool player, but I was in the zone. I was just clearing the table. So this curator remembered me and a couple of years later, probably in 2000 or 2001, he was in Toronto for something and we were in a taxi, and he said that for years he had been wanting to use that phrase as the title for a show he was curating. So he asked my permission. I was like, “Dude, I don’t even remember saying it.” Then a year later he comes to me and says, “We’re doing an interesting show with you.” So I ended up doing a show that included Glow House Birmingham, a version of Hiccup and a sound piece and a video. And we called the show “Everything is interesting.”

But it is a kind of modus operandi for you. Everything is interesting for you, especially the commonplace rituals out of which you generate work.

It’s a state of mind, right? I was 40 or something when I came up with Glow House. How many times had I walked down a street and seen a house with a glowing television and kept walking, even as an artist? It’s just that one day it was interesting. It’s not that everything is interesting; it’s that at some point, everything is.

Still Life #8, 2013, graphite drawing series, 8B graphite pencils on wood and matte spray varnish, 11 x 12 x 11 inches.

One of your Everything/Nothings is “Everything comes down to love,” and the response is “Nothing else matters.” You mentioned earlier in our conversation that you’re a romantic. I sense that underneath this rough exterior is a romantic-in-hiding.

For sure.

Love is spoken about in so many of the pieces and in so many guises: frustrated love, disappointed love, wished-for love. But the aspiration remains that love is possible and that you’re looking for it.

Yes. I don’t think I’m a cynic. But what has been surprising is how much regret there is in the stuff I’ve been remembering. That’s been a thing for the last few years. Again, it’s about getting old. It’s a stereotype. When you’re young, you’re hopeful. When you’re old, you have regrets. But I think that’s interesting. I’m trying to wrap my head around a triple split screen of my past self, my present self and my future self as a way of dealing with it.

Do you even know what your future self is going to think?

It’s all about your present self, how you remember your past, how you remember you imagining your future. ❚

Strategy For Immortality, 2016, cross-stitch on linen, 24 x 24 inches.

My Happy Place, 2016, cross-stitch on linen, 24 x 24 inches.