The Voice of Moving Meditation

An Interview with Meredith Monk

Meredith Monk defies description. The body of work she has made in a legendary 50-year-long career is unequalled in its range and inventiveness. She is a composer, singer, choreographer, filmmaker, installation artist and creator of opera and music-theatre works.

Her early training and experience encouraged a sensibility that was already searching for ways to integrate sound, image and movement into one form in which “all units had their integrity.” Her education at Sarah Lawrence, where she studied in both the voice, theatre and dance departments, her training in Dalcroze Eurhythmics, a system of learning in which music and movement were understood as equivalent inspirations, and an atmosphere of interdisciplinarity in mid-’60s New York all fed her synthesizing imagination. In the following interview she remarks how much she loved the “anything-is-possible mentality” that characterized the city when she moved there in 1964. Her gifts and imagination took its permissions to heart, and in a unique way, she made everything possible. As Alex Ross put it in The New Yorker, she has “mapped a world that never quite existed in the history of the arts.”

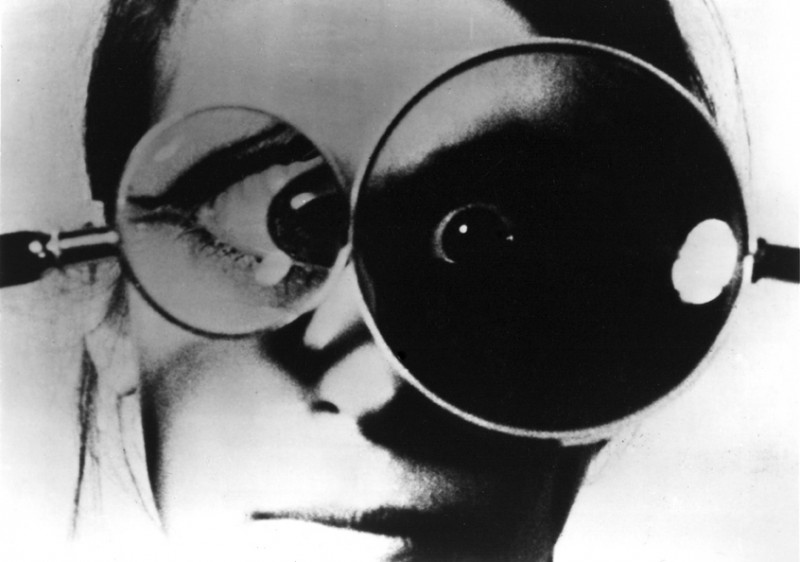

Meredith Monk, 16 Millimeter Earrings, 1966. Photo: Kenneth van Sickle. All photos courtesy the artist.

While she is disciplined, she has never taken any definition of a discipline as a limiting frame within which to work. She has famously said that she works “in between the cracks, where the voice starts dancing, where the body starts singing, where theatre becomes cinema.” To use one of her own formulations, the voice is “the soul’s messenger,” and she is always finding meaning in the connections between things. Anyone committed to the interstitial embraces the word “between” because it is there that we find the tissues that connect one thing and one idea to another. Monk situates her work in “that space between language and abstract music. I love that ambiguity. It’s like another crack. I love those places because I think you’ll find things there between the cracks.”

Her own assessment is that she has been exploring what she calls “primordial utterance,” sound that comes before language and that makes a language of its own. When you first hear the articulated sounds in a Monk composition, you think you’re hearing language caught in some process of deconstruction or invention. It is a soothing indeterminacy. Finally, you give over to its own sense of being and becoming in the moment. Her music has a tendency to obliterate measures of time. Many commentators have remarked that her music sounds simultaneously ancient and futuristic; we feel it is deeply rooted in our core and we feel equally that we are hearing it for the first time. She is a time magus.

Her most recent CD, On Behalf of Nature, is both a celebration of Nature and a warning on its behalf. When I asked if her prognosis about our future was positive, Monk responded with a gentle equivocation. The world will keep on going, even though our stupidity and avidity may be severe enough to exclude us from the process.

What I am assured of is that what she has made will be part of that ongoing continuum. An artist who has repeatedly made the boundaries of time irrelevant is an artist whose work will move alongside time throughout its infinite measure.

_566_720_90.jpg)

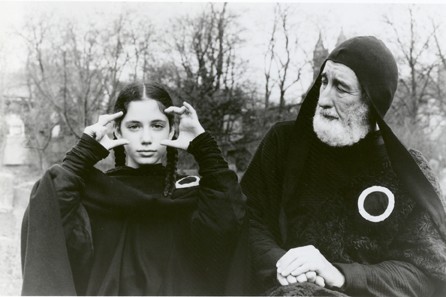

16 Millimeter Earrings, 1966, Judson Memorial Church, New York City. Photo: Charlotte Victoria.

On the first evening of the 2017 Winnipeg New Music Festival in January, the WSO will present WEAVE for Two Voices, Chamber Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Alexander Mickelthwate, with vocalists Katie Geissenger and Jeffrey Gavett. The next evening, Monk and her ensemble will perform a selection of works she composed between 1969 and 2008, and a selection of her choral works will be included in the third evening.

The following interview was done by phone to New York on October 20, 2016.

BORDER CROSSINGS: You’ve always said the body and the voice are not separate but when you first went to Sarah Lawrence you were more interested in movement than in voice.

MEREDITH MONK: I was actually in both the voice and the dance department and I also did some theatre work. In my senior year they allowed me to take two-thirds of my studies in a combined performing arts program where they let me design my own major. I was very dedicated and disciplined even in my academic studies. Sarah Lawrence was an amazing, progressive institution.

Was there an ‘on the road to Damascus’ moment when you realized how central voice was to what you were doing?

Well, my mother and my grandfather were singers, my great-grandfather was a cantor and my maternal grandmother was a concert pianist, so music was my first language and was very natural to me. I had the aspiration to become a singer, but movement was also a part of my childhood. I had some physical challenges and so I’m always very grateful that my early training was in Dalcroze’s Eurhythmics, which is a combination of music and movement. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who was a Swiss composer and educator, says that all musical ideas originate in the body.

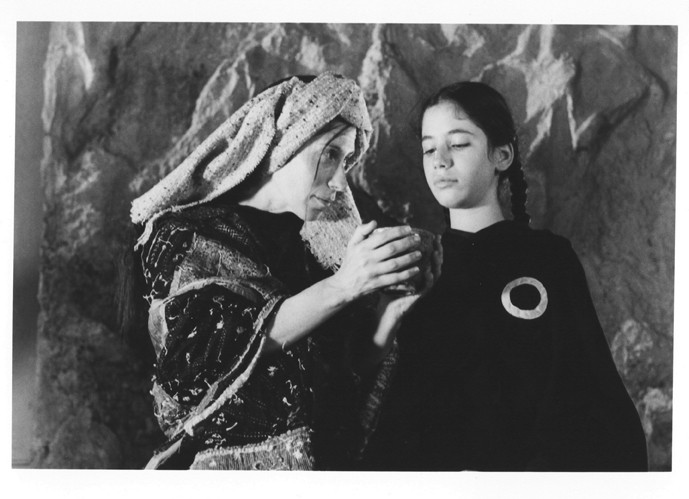

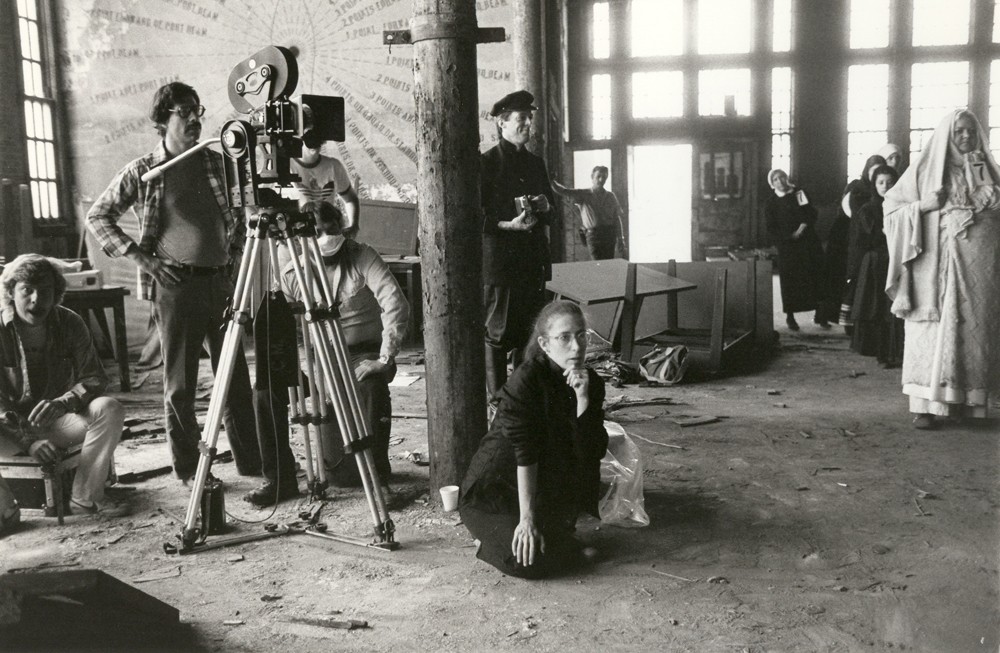

Crowd Scene from Book of Days, 1988. Photo: Jerry Pantzer.

So you would have been more interested in kinaesthesia than synaesthesia?

Not really, but I did come from a different background than the other children in Dalcroze. They were learning music through their bodies and I was learning my body through music. I came into the classes feeling confident about music and rhythm.

You said that you felt somewhat awkward because movement didn’t come naturally to you, so in some senses you had to learn more about it than about the capabilities of your own voice?

Exactly, because I have strabismus, which is an eye condition where I can’t fuse two images. Most of us look out of two eyes and we fuse the two images into one that has three-dimensions. I’m actually looking out of one eye at a time and my brain compensates for that. So if you close one eye that’s what I am seeing. I’m seeing distance but not that curved, three-dimensional aspect of an object.

And yet you talk about sculptural space.

The irony is that I have always dealt with space. Another thing about Dalcroze training is that it is music in space. Space is an ally. I always talk to singers who come from the classical tradition about that because they were never taught about space. Dalcroze was interested in a three-pronged pedagogical system—one was rhythmic training, one was solfège training and one was improvisation, so in a sense it was very synaesthetic. For example, we would sing the “do re mi fa so la ti do” scale but then we would delineate it with our arms in space and also read it on paper. Perhaps this is the synaesthesia you were talking about earlier. I didn’t realize how much that had influenced me until many years later when I was working on ATLAS, an opera for the Houston Grand Opera. The Western classical system is not that complex rhythmically; rhythmic articulation is not actually in the forefront, it is more about line than rhythm. So I would show the classically trained singers a piece of material and then I would sing it and they would ask, “How are you going out into all those rhythms and then coming back around again?” I would say, it is very instinctive and their response was, “It’s that Dalcroze training.” That’s when I realized it was more of an influence than I had thought.

You’re only 21 years old when you come out of Sarah Lawrence, and you seem fairly precocious.

My first piece in New York was called Break. I performed it in the Washington Square Galleries. I had been very influenced by cinema. It was a solo piece, and for me every piece has a question. When you find a question you are on the right track; the question for Break was: how do you do a solo form that has some of the syntax of film— fast cuts, perceptual changes, changes of persona, discontinuity and disjunction—and how do you do that as a soloist? The piece was very gestural, it had some voice, a few words and it also had a soundtrack. I made a multitrack soundtrack— fragmented collages of car crashes—by using two tape recorders and building tracks by taping from one machine to the other.

Scene from Book of Days, directed by Meredith Monk, 1988, left to right: Toby Newman, Pablo Vela. Photo: Dominique Lasseur.

Had you been following what was going on at the Judson Dance Theater before you came to New York in 1964?

The Judson Dance Theater started when I was still in school in 1963. I remember coming into New York in the summer and seeing some of those first concerts, which were really wonderful. What was interesting about Judson was the artists were coming from all different disciplines and they were trying to break through the boundaries by trying another discipline. Most of them went back to their original discipline but they had increased their vocabulary by working in another form. Those concerts were disparate because people’s approaches were so diverse. I think that critics always think of Judson as having one particular sensibility, but there were actually many people with a wide range of approaches. The concerts were very long and you never knew what was going to happen next. I loved that “anything-is-possible” mentality and even as a student I was trying to find new things for myself before coming into New York. By the time I got to New York the Judson Dance Theatre no longer existed as a group but the Judson Church was available. I did do a few of my performances there because Al Carmines was very open to having young people perform.

You have famously said that you work “between the cracks where the voice starts dancing and the body singing.” Was that a natural place for you to be where you recognized that the various art forms could be part of the same sensibility, or was it something you had to work on to develop?

I think it was a necessity for me. Through my childhood and adolescence I did have these different interests and talents, and weaving together perceptual modes became an urgent quest because it was a way of integrating myself as an artist and a person. After a few years of working that way I started thinking about how art forms in the Western European tradition were separate; singers just sang, musicians just played instruments, dancers just danced and actors just acted, whereas in ancient cultures those performance forms were integrated. There wasn’t this specialized way of thinking about things. I realized that weaving together different elements could be an antidote to the fragmentation that we had in our society.

Robert Rauschenberg said that he operated in the gap between art and life. Did you have anything in common with his notion about the source and location of art?

We were all thinking in those terms. His style was different from mine and he came from a different generation, but I think we were all contemplating what art really was and how that related to our lives.

Yvonne Rainer has the notion that you can get magic out of the ordinary, and a lot of what was going on in New York in those days was a recognition that the quotidian could be magical and could be lifted into art.

I think so. The Fluxus people, like Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles and Geoff Hendricks, were always very concerned with that. I remember one of Alison’s performances was just making a salad, and I think she still does it. Joseph Beuys was very much into that as well.

Meredith Monk and Toby Newman, Book of Days, 1988. Photo: Jerry Pantzer.

There is a European model for this, although he comes out of a completely different sensibility, and that is Antonin Artaud and his conception of the all-encompassing environment. Were you aware of his writing or was that European sensibility outside of the American experience?

I’d love to talk about Artaud but there is one other person who comes to mind and that is Duchamp. His work was very revolutionary in that ordinary objects, just by the context or the bracketing, could be called art. A lot of that thinking started with him and then it went to John Cage and from there to the following generations. I had been in New York for a year and a half and someone said I should read The Theatre and Its Double, which I did. I appreciated and was encouraged by it because I was coming from a non-verbal tradition and was working vocally and wasn’t using text. His critique in The Theatre and Its Double was about the naturalistic play tradition and linear narrative. He had been inspired by seeing Balinese theatre, and of course I felt very close to the idea of a multi-perceptual performance form, but had found it in my own way and in my own time.

It must have been a terrifically exciting time.

It was. I talk with young people today and they have a longing for that world because survival was possible. I could teach children’s music classes, model for artists and could live in an apartment by myself. I lived in a little garret attic apartment in a West Village brownstone where people had to bend down to get in the door. A lot of people were living in tenement buildings and they can’t do that anymore. If young people come to New York now, they have to live six to an apartment and have a regular nine-to-five job in order to survive. Our impulse to make art was coming from a place of sheer love and devotion and I think people long for that right now. They will find ways to do it. I think of art as an antidote to what’s going on in this world and it does offer an alternative. We need it and our souls need it. It’s a sad, dark time.

16 Millimeter Earrings (1966) is such a rich piece and one of the things it does is quote Wilhelm Reich on “the excitation of the sexual zones.” His writing was influential on Carolee Schneemann and James Tenney in Fuses. Were you aware of what Stan Brakhage or Carolee were doing in film in the mid-’60s?

I wasn’t aware of their film work but the other morning I woke up thinking about Meat Joy. Carolee was part of an older generation but I remember being especially impressed by that piece. It was sensuous, almost like seeing the energy of an abstract expressionist painting in three dimensions, but transformed by her unique sensibility.

I gather you were interested in surrealist film?

Absolutely. Around the time of 16 Millimeter Earrings there was a big show of Surrealism. I never saw the show but I remember Artforum devoted a whole issue to it. I was interested in modes of perception and also psychic landscapes. This way of thinking was very rich for me at the time.

Your imagination was like a sponge; you were absorbing ideas from everywhere.

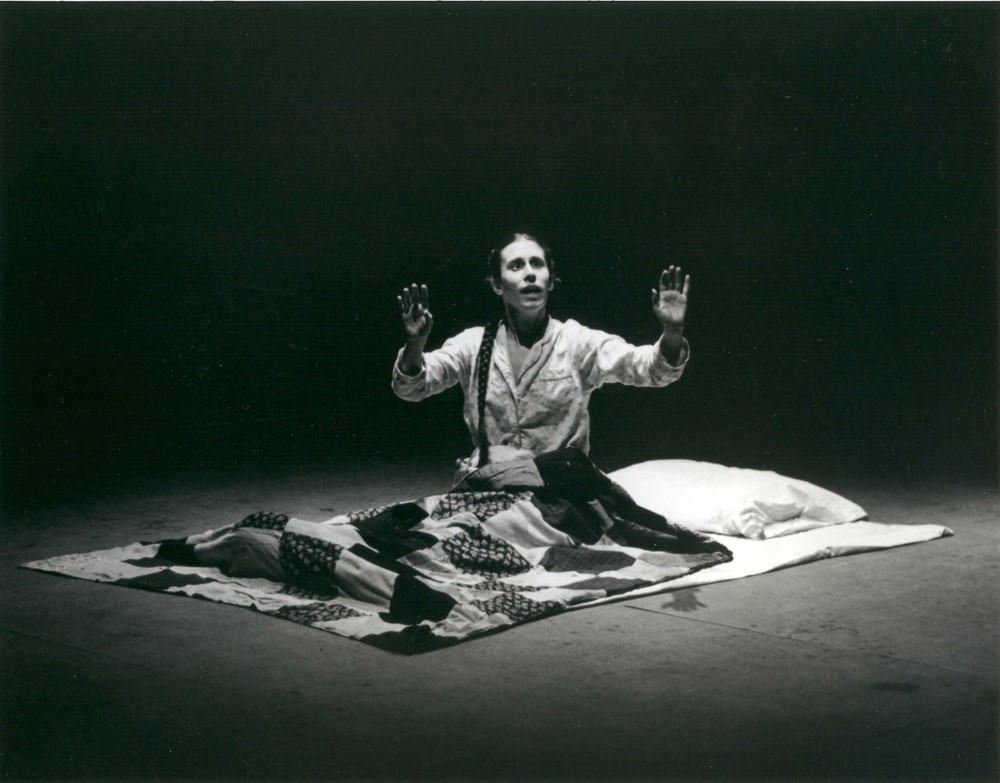

Meredith Monk directing Book of Days, 1988. Photo: Dominique Lasseur.

I was 23 years old and I was reading and seeing a lot but I was already sifting it through my own sensibility. I feel that’s how you come to something unique and authentically yours.

Let’s talk about uniqueness and ownership. When did you realize what an extraordinary voice you had? You talk about recognizing that the voice could do practically anything; was it your particular voice that could do anything more than anyone else’s?

Because of my family background I had a voice that had a wide range to start out with, I was musical and had good intonation. Soon after I came to New York, I had a revelation that I could work with my voice as an instrument and that it did not need language because it was a very eloquent and ancient language in itself; that within it were male and female, different ages and landscapes, characters and myriad ways of producing sound. From that point on, I began exploring what my voice could do. As a young artist identity is a life-and-death issue, and when I had that revelation about the voice, I knew what the core and heart of my work was going to be.

Brakhage and Schneemann were being autobiographical in their film work—in Fuses Carolee and Tenney actually make love, Window Water Baby Moving was a record of the birth of Brakhage’s child. You end up using autobiography but in a less direct way. Were you staying away from your self as material in your work? I’m interested in how you used your life in your work.

It’s a wonderful question. In 16 Millimeter Earrings I did have the thought that I could use anything in my life as material, whether it was an object, a physical part of my body or something I was reading. But my impulse was not to stop there; I wanted to make something that was universal and that went beyond me. Maybe that was a slightly different impulse.

Did you come up with the description that what you do is duets for solo voice?

Yes, there’s a song called Click Song #1 where I am singing a melody and producing clicks in irregular rhythms simultaneously, and another called Hungry Ghost, which is a dialogue between different vocal qualities. They are both from a song cycle, Light Songs, that always has more than one thing going on within the voice in each solo piece.

And because you have a three-octave range you can be more than one voice?

Yes, you can hocket with yourself. With the “Click Songs” people ask, “How are you doing that, you’re singing this melody and then you’re clicking these different rhythms on top of it?” For me it seemed quite natural and not at all difficult, but I can see that just hearing it may make it sound quite complex.

Ping Chong, Meredith Monk, Paris, 1974, Festival d’Automne, Paris. Photo: © Beatrice Heyligers.

You’ve said that you want to put yourself in a position of risk, and to do that you never want to use the same formula. You’re talking about placing yourself in a condition of vulnerability. Do you still feel vulnerable?

That’s the beauty of performing. Performers are on a tightrope and the audience can feel that. You’ll see in the Quartet Concert, Katie Geissinger and I will sing a version of the hocket from Facing North, and that is one of the most vulnerable pieces to perform.

You did it with Robert Een, didn’t you?

I made it for Robert and myself and then I sang it for many years with Theo Bleckmann, also a wonderful singer. Katie and I do a version for two women.

So is that particular piece anxiety-producing?

You’re throwing these notes back and forth and it is very, very precise and fast. It is also completely interdependent. If one person makes a mistake or falls, the whole thing falls. After performing it so many times we have learned how to get back, so if you’re leaning off the tightrope and are about to fall, you can get back on. That’s part of the technique of that piece. It’s like a moving meditation; if you’re thinking; then you miss. You’re going so fast and it requires such coordination between two people that if you have a thought, it gets in the way. But if there is a mistake, both people have to decide, are we moving forward or are we going to actually go back and correct our mistake? Oh my goodness, there have been some very wild solutions on stage.

Have there been times when, instead of trusting the emptiness and uncertainty that you talk about as being at the core of your approach to composition, you have doubted the doubting? Has the doubt seemed less a gift than a curse?

Sometimes I say to myself, “Shouldn’t it be easier after 50 years?” But I try to start with beginner’s mind each time and not take anything for granted. The beauty of it is that the fear at the beginning of the process, little by little, starts turning into curiosity. How could it ever be comfortable hanging out in the unknown? So you learn how to tolerate it and be playful with it.

There is also a deep sense in your work of what I want to call the spiritual. It is not an attachment to any particular religion but rather seems an aspiration towards the transcendent. At the same time, there is something profoundly primordial about your sound. It’s almost as if time doesn’t matter, or that you somehow occupy all times simultaneously.

That’s exactly what I’m trying for and thank you for saying it so eloquently.

Is that because you believe the primordial origins were a couple of people standing and grunting at one another, and in recognizing utterance as the key to communication, you see that is where music comes from?

I think probably music came before utterance. There is a wonderful book by Oliver Sacks called Musicophilia, where he writes a lot about utterance. In it is a fascinating account of ancient people. Apparently, everybody was born with perfect pitch in ancient times, and then when language came in, people lost that capacity. So you could say that a person who has absolute pitch still has that part of their ancient brain. And of course, scientists have done studies with pitch languages like Mandarin, for example, where someone will say something and a week later say exactly the same thing and it will have the exact same pitch. It is difficult to know whether utterance or music came first, or whether they are both the same thing. I don’t think utterance was just grunting, but a very nuanced set of sounds. I think music goes deeper than language. That is why I have had the privilege to do my music all over the world, because people don’t have to go through the filter of language to understand the music or respond to it emotionally.

Dolmen Music is a wonderful piece in this connection. Was it inspired by seeing the Fairy Rocks in Bretagne?

Yes, but I didn’t make the connection with that experience until after I had started working on the music. I saw the fairy rocks while performing in Rennes, when a few of my ensemble members and I went into the country and came across these dolmens. Somebody who had grown up in the area told me about them. I was astounded; there was some kind of mysterious energy there. You’re right in the middle of farmland and then all of a sudden you’re in this place that has so much energy. The standing stones are huge and there is also this gigantic slab, and you wonder how they got it up there. I’m sure it can be explained by levers and some kind of rolling platform but the mystery of it was what appealed to me. We went inside the dolmen and sang a canon from Quarry.

Dolmen Music is a classic example of your music sounding old and futuristic at the same time.

Old and futuristic is exactly what I’m trying for. I’m after a circular sense of time.

As a Buddhist, the notion of circularity rather than linearity is a more appropriate way of thinking about time.

It’s just much more spacious.

There is a moment in Dolmen Music when Robert Een is bowing the strings on the cello and you lean over with some sticks and play a little percussive riff. It isn’t Bang on a Can, but it is very catchy. Was that planned or improvised on your part?

That was definitely part of the piece. It uses the vibration of what he’s doing with the bow in counterpoint to what the person playing the chopsticks is doing. Sometimes that person just places the chopsticks on the strings and the vibrating strings make that little sound.

Impermanence, left to right: Katie Geissinger, Ching Gonzalez. Photo: © Michael Cooper.

When I first listened to the unrecognizable language in the piece I thought it was language deteriorating, but then I realized I might have it all wrong. It could be the invention of a new language.

If you don’t know the language or you’re hearing it from far away and barely making it out, it can seem like another reality. I think some of my pieces really do occupy that space between language and abstract music. So in something like Porch you almost can hear words but you don’t. I love that ambiguity. It’s like another crack. I love those places because I think you find things there.

Quarry (1976) seemed to be your entry into a place where history and myth and archeology intersect. What were the complications of doing that piece from a personal point of view?

When I did Juice, I was trying to subvert notions of time and space in a performance. Juice was performed in three spaces beginning with the Guggenheim Museum, and ranging over a month. Now people are calling it durational performance but at that time there was no name for it. I wanted to break the habitual pattern where you go to a performance and you have coffee and you talk about whether you liked it or didn’t like it and then the next day you don’t even think about it. I also wanted to have memory be part of the experience. With Quarry I wanted to make a poetic documentary form, taking real history and real events and abstracting them in such a way that they became more universal. On some level it does have that personal layer because I come from an Eastern European Jewish background. I always think what would have happened to me and what would it have been like, say, to be in Paris if my neighbours and I had been taken. Even before Quarry I’d been a student of World War II.

Did you shoot the haunting footage in the Vermont quarry?

Yes, I directed it and my good friend David Geary shot it. Do you want to hear something that is really haunting? I love working with scale and with the disjunction of space that you can get in film but can’t get on stage, so I shot that film. I already knew that the piece would be called Quarry. Then a few months later we were doing a tour of Education of the Girlchild at the Venice Biennale and we came up to Amsterdam and then to Paris. I had heard there were extensive World War II archives in Paris. I can’t remember the name of the museum but I vividly remember the archive. I was looking through photographs of people in concentration camps when I came across a group of photographs of Jews hauling big stones in a quarry. I was floored. They could have been frames from the film we had shot in Vermont the previous August.

In the past you have used the phrase the “collective unconscious,” which is a Jungian term that incorporates the idea of the archetype. I gather you subscribe to that notion as a structure of human experience?

Jung was very important to me. Today a lot of people are anti-Jung and anti-archetype because the feeling is that he had a racist basis for these ideas. My understanding of archetype is different; I think of it as recognizing that there are existing forms in every culture. There was a period where I was making what I would call archetypal song forms. For example, a lullaby would be an archetypal form because it exists in every culture.

Quarry: An Opera in 3 Movements, 1976, La MaMa ETC, New York. Photo: Nat Tileston.

Quarry has a sound bed of music throughout, except for the section in the quarry. It made me think of Theodor Adorno’s lament that after Auschwitz there can be no poetry. I wonder if in certain ways events like the Holocaust cancel out the possibility of aesthetic articulation.

That was definitely my question with Quarry. There was music from beginning to end and the underlying source was World War II but I tried to make it wider, more a meditation on war. For example, Ping Chong played the Dictator and we really worked hard on making a kind of composite dictator. He could be Hitler, Mussolini, Mao Tse-tung, or Pol Pot. They all destroy themselves in the end, but I wanted to understand the dictator mind. I remember some rehearsals where all of us made our own dictator character as a way of exploring the notion that we all contain that possibility within us. We could inhabit that aspect but we choose not to descend to that level of megalomania and psychosis.

There are dark moments in your work, but On Behalf of Nature seems to counteract the darkness with humour.

I love humour. I would hate to do any piece that doesn’t have humour in it. Shakespeare had funny scenes even in the darkest tragedies. I remember a number of years after I had done Quarry, I saw Roma, citta aperta (The Open City, 1945) by Roberto Rossellini. There is a scene where an old man is in bed and the Nazis are coming into the building. I think it’s Anna Magnani’s father or grandfather and they are afraid he will start talking and give them away, so the priest hits him over the head with a frying pan to knock him out. You actually laugh at that moment. The timing and juxtaposition make you realize what a genius Rossellini was. You have to have these moments of relief in tragedy. I have also done works where overall the piece has a comic quality but within that there are poignant scenes.

Quarry: An Opera in 3 Movement, 1976, La MaMa ETC, New York. Photo: Nat Tileston.

Did the soundtrack come before the images in Ellis Island or were they made to suit the mood?

The images came first and then I added track afterwards. You know, working as a composer and a filmmaker is very interesting. It creates a dialogue between the director part and the composer part within the same person. That really applies to Book of Days, where I worked on both the music and the film simultaneously. The first manifestation of Book of Days was a music piece I premiered at Carnegie Hall in 1985, but I was thinking about the film at the same time. There were points in Ellis Island and Book of Days where I wanted to develop the music further because my forms had become much more complex musically. But then the filmmaker part of me would say, we only need 60 seconds of this music. So it can create an odd dialogue when you’re doing both things.

If Gertrude Stein were a singer I think she would have written Insect. And the movement in that piece looks like a crazed semaphore.

Insect Descending has the movement you’re talking about. The inspiration came from being focused in on watching a fly washing itself. I was looking at how strange those movements were.

Is form primarily found in the making for you?

Yes, that is usually the way I work. Finding new forms is very exciting for me, so I usually begin without knowing what it will be. But with film you can’t work that way, because of the expense. I storyboarded with Book of Days with my collaborator Yoshio Yabara. It was a one month long feature-length film shoot, so there was no way I could wing it; I had to be really prepared. But when something comes up in the moment you still try to pay attention. And mistakes are always good because you learn a lot from them.

The trouble is once it has become a form then the possibility of those accidents and mistakes diminishes.

That’s the difficult part of both recordings and films and why I continue to do live performance. I love the organic nature of live performance. It’s born at a certain point and you’re not sure what it is until it is born and then, little by little as you perform it, you find out more and more about it, and it grows into a toddler, then it’s an adolescent and then an adult. It always has the possibility of change and modification and that is the aspect I love.

Has the work moved away from conceptual notions to something closer to a kind of sound phenomenology?

Yes, I think it has become less concept and more working directly with the materials themselves and letting them lead me to where I’m going.

I wonder why that has happened? Do you trust the process more than you did when you were younger?

I wonder that myself. When I was a young artist, concept and ideas were so important. I remember reading something by John Cage when he said that one can have too many ideas. In those days they were very important. It’s not that I don’t have ideas now, but I guess I dig down more into the material that comes up and try to find my form from that.

The delicacy of the lyrics in the between song from impermanence is very moving. I mean, “between the seed and the dirt” is about the most economical journey from life to death you could come up with. That song was written by a close friend of yours who died, wasn’t it?

Yes, it is mostly Mieke van Hoek’s text. We’ll sing it in Winnipeg. I found it in her notebook after she died. You know, only Mieke would be sitting in a café thinking about what is “between the rug and the floor.” Who thinks in those terms? I changed her English a bit in places because she came from Holland and some of the lines didn’t scan easily, and I added “between the lipstick and the lips” and “between the seed and the dirt.” She was working on the idea of boundary in a physicalized way.

You construct an equivalently beautiful formulation in The Soul’s Messenger, where your voice is wings and also your pick and shovel. Those wings are about transcen- dence but it is also about hard work. Inspiration is one thing but you also better be a good shoemaker.

Meredith Monk directing Ellis Island, 1980. Photographer unknown.

Exactly. How many times do you get that inspiration, and what happens if you don’t? You have to keep up your craft.

Does the shoemaker have to work harder than the wings that will carry him away?

It is all hard but rewarding work and has a lot to do with discipline. I have to be disciplined to keep my voice healthy and strong and the same with my body and hands for playing. It is a lot of work just to keep the instrument going and then the composing is another aspect. But I love the discipline; it is a wonderful thing.

In On Behalf of Nature you talk about wanting to conserve the world, which moves you in the direction of bricolage. Was that an ethical decision?

Yes. Here we were making a piece about ecology and so if I pushed it, how would the process of making have the same principle as the idea of the piece being made?

Were you looking for a different kind of balance between voice and instrumentation? There are a cappella pieces and many that are instrumental.

I’ve had the good fortune to work with a brilliant ensemble over many years. I love making pieces with the same people and then trying to find new musical possibilities each time. In 2003, I made my first full orchestral work for the New World Symphony. Michael Tilson Thomas tried to convince me to do it for years and I finally gave in. It took me five years to complete. Before that I always felt that the voice was everything, and I wanted to keep my instrumental writing simple and transparent, so that the voice could be free. But then I got interested in how I could make my instrumental texture a little richer and that opened up other possibilities. After writing some orchestral and chamber pieces, I could go back to the three instrumentalists in my ensemble, John Hollenbeck, percussionist, and Allison Sniffin, singer and multi-instrumentalist who plays French horn, keyboard and violin, and reed player Bohdan Hilash, and expand their parts. Bohdan plays everything from a tiny Asian flute to contrabass clarinet and saxophone. The three of them are a wonderful band within the larger group, and I wanted to make some instrumental pieces that they could play.

I was a bit perplexed by Water/Sky Rant; there is the insistent harp, and what sounds like baby noises, and a woman’s voice that seems to be fighting for breath. I can’t tell if the baby is excited or agitated or crying. I was trying to understand the language in that particular piece.

Impermanence, 2006, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, left to right: Theo Bleckmann, Ching Gonzalez, Katie Geissinger, Meredith Monk, Allison Snif n, Ellen Fisher, John Hollenbeck, Bohdan Hilash. Photo: © Michael Cooper.

What I was working on in Water/Sky Rant was a kind of Cassandra shaman character, and the rant is a warning to wake up. The piece also is a lament and a lullaby for the world.

The final two pieces, Ringing and Spider Web Anthem, which is a complicated web of sound, constitute what you call an “extended coda” that suggests the resiliency of the world. Are you hopeful?

I guess I do trust that something will go on living, even if human beings are totally ignorant, destructive, careless and not appreciative of what we have. We’re just asleep. But I have confidence that the world will somehow go on. The spiders will keep on spinning. I made Recent Ruins in the late ’70s, which included the very last section of Dolmen Music as the end of that piece. In a totally dark space I had people who were wearing portable light belts like they use in film. They are battery-packed and are very bright. There were giant spiders on sticks and huge turtles with remote-controlled cars inside them moving across the space. The structures of those insect and reptile forms have remained the same for millions of years, so they may outlive us.

Is Panda Chant II just fun?

Panda Chant II is really fun to perform. The strange thing is that it was originally made for a piece called The Games, an ominous science-fiction opera. Ping Chong and I collaborated on the libretto and I composed the music. It’s a pretty apocalyptic work. We made it in Berlin in late 1983 when missiles were pointed from East Berlin into West Berlin; it was right before the 1984 Olympic Games; and it was going to be “1984.” In the opera, the world has ended and a group of survivors is living on another planet, or in a spaceship, and the community slowly evolves into a mirroring of what happened on Earth; it becomes a kind of fascist society. So Panda Chant II in the context of The Games is quite frightening. The Gamemaster becomes a dictator—at first he’s a rock star, and then gradually you realize he is a truly sinister demagogue and his followers perform a kind of fanatic chant for him. But over the years Panda Chant II has turned into a joyful, celebratory piece. We’ve done it with hundreds of people and it’s wonderful to perform. Were we to do The Games again, I’m sure that we could restore that sharp, relentless quality but I love that it has evolved into a different piece. What is so beautiful is that music is a live form that can keep on changing and growing. ❚