The Poetics of History: An Interview with Rebecca Belmore

One of the central concerns of Fountain, Rebecca Belmore’s performance-based video installation at the Canadian pavilion for the 2005 Venice Biennale, is water. Her recognition of its importance in our practical, political and imaginative lives is complex. “The power of water is something that we understand,” she says in the following interview, conducted the day before the vernissage opening at the Biennale. As Canadians, water is what we have in abundance, and what the world, including the United States, wants. Water is also a symbol for the rich cycle of life and death that frames human experience.

Fountain, 2005, Sketch No 2. Photograph: Raj Grainger.

Belmore brings to Fountain an acute awareness of her myriad roles as a performance artist, a woman, an Aboriginal person, a North American and a citizen of the world. The manner in which these identities overlap and compete with one another is among the more fascinating aspects of the work. As a North American Aboriginal person, she is aware that the fountain functions as an emblem of European culture and conquest, which places her appropriation in the arena of cultural politics. But as an Aboriginal woman, her transformation of water into blood is a potent occupation of a range of identifying positions running from essentialism to our attachment to a destructive primitivism. Fountain acknowledges the human predilection for brutality and violence at the same time that it acts as a mediating force in the troubled, ongoing relationship between Aboriginal and mainstream society. She insists upon emphasizing an indigenous viewpoint, which, she argues, is “too often dismissed as being trivial.” Her characteristic way of drawing attention to that trivializing tendency is to find a resonant dramatic gesture. In this particular case, she was aided in that search by Winnipeg filmmaker Noam Gonick, who directed the video sequences that form the substance of Belmore’s “performance” in Fountain: “When I hurl the contents of the bucket and it washes the screen with blood and I stare at you from one side and you’re on the other side, I think that really is the question: How long do I have to do this? How long do I have to say, ‘Look at us and listen to us’?” While not exactly a pair of rhetorical questions (the answer to which would be “forever”), they are interrogations coloured by the problematic history of Aboriginal/white relations. What prevents her from sinking into either rage or despair is her ability to build into the work a sense of beauty. “With art you can make beauty,” she says, “and at the same time you can address the ugly.” Her performances over the years are proof of how remarkably effective the work has been in elaborating this full aesthetic range.

In the following interview Belmore quotes the observation made by her friend and colleague, N. Scott Momaday, who says “we have no being beyond our stories.” Belmore’s own sense of being an artist is inescapably connected to a visceral sense of narrative, whether she revisits the massacre site at Wounded Knee in South Dakota, or ritually situates a sympathetic space for the women missing from Vancouver’s Eastside. She is an artist whose performances are characterized by a sense of restrained passion; the restraint emerges in her unerring sense of reduction. In this regard, her storytelling is a kind of performed poetry in which epic stories of struggle, pain, ecstasy and triumph are compressed into the simplest, most economical narratives. She says modestly that “I’m just here to mark things down,” and then adds, more accurately, “to make history.” When the story of Canadian art gets told, it would be safe to bet both water and blood that her marking will be end up being historic.

Rebecca Belmore was interviewed by Robert Enright on June 8, 2005. Fountain, which will be on exhibition through November 6, was organized by the Kamloops Art Gallery and the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia.

REBECCA BELMORE: We are part of nature, we are elemental, we destroy and we create, and I think that is what the work is really about. And it raises questions about how we’re going to deal with water in the future. That’s my major concern and what I hope people from the international community will get from the piece. I live in Vancouver, a fountain-obsessed city in which fountains are used as decoration and architectural enhancement. But at the same time, I know that fountains are from this part of the world. So for me as an Aboriginal person, to bring the fountain back to Europe is very meaningful. It’s saying, you’ve gone out and conquered, but now what are you going to do? What are we going to do? And it’s interesting because water is a resource in Canada. We’re wealthy with water. Maybe it’s more valuable than the oil we’re pulling out of the ground.

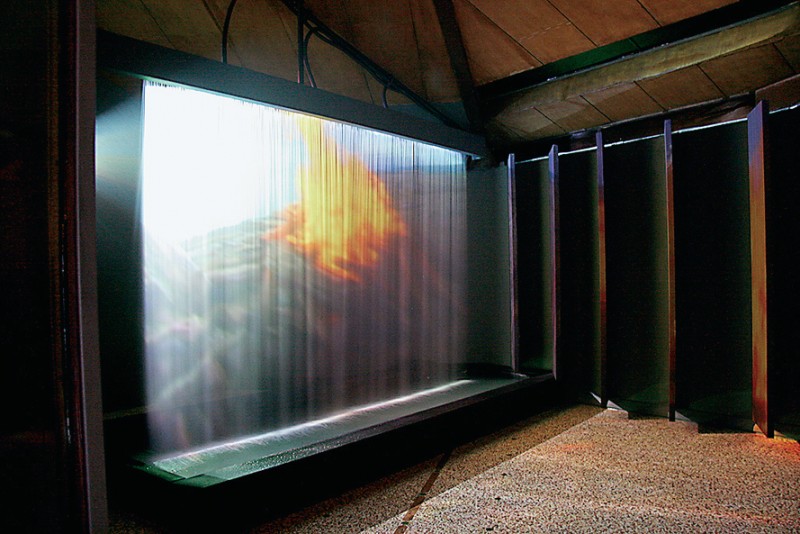

Fountain, 2005, installation Canada Pavilion, 2005 Venice Biennale. Photographs: José Ramón Gonzáles.

BORDER CROSSINGS: You said earlier that this piece isn’t political, but in the way you’re talking, it clearly has an implicit—if not an explicit—political message.

It does and so does a lot of my work. I try to balance it with beauty. I’m just a person and not an expert, by any means, but it’s my role as an artist to articulate the questions we should be asking. Without being obnoxious, that’s what artists should do.

You’re very specific about the sites you choose. What made you choose to do the video for Fountain in an industrial site?

It’s an amazing and totally charged site in terms of its history. Because at Iona Beach, you have this sewage, which you can see in the video, but if you don’t know what it is, you wouldn’t recognize it. For me, it’s significant to have it there because it’s a four-kilometre pipe that goes out into the ocean—there is a filtration plant and it’s pushed out back into the ocean. Then south is the airport, so it’s an international site. Then north on the beach, you have these abandoned, renegade logs from the logging industry. We all know how that affects the environment and the rain forests. Then beyond that and across the mouth of the Fraser River is the Musqueam Band—I think they’ve had a Longhouse there at least for a thousand years. So as a theatre for the video and a theatre for my thinking, that site was really intense.

Is it a curiosity for you to be working in a space—the Canadian Pavilion—that is often described as a tipi?

It’s a silly idea to think that it’s a tipi. That description is part of the whole trivialization of our way of living and our architecture. I mean, the pavilion is an horrendous architecture to work in as an artist. I’d rather work in a tipi.

Is it inevitable that your relationship will always be one of either benign or intense outsiderness with regard to mainstream culture? Will you always be on the outside looking in?

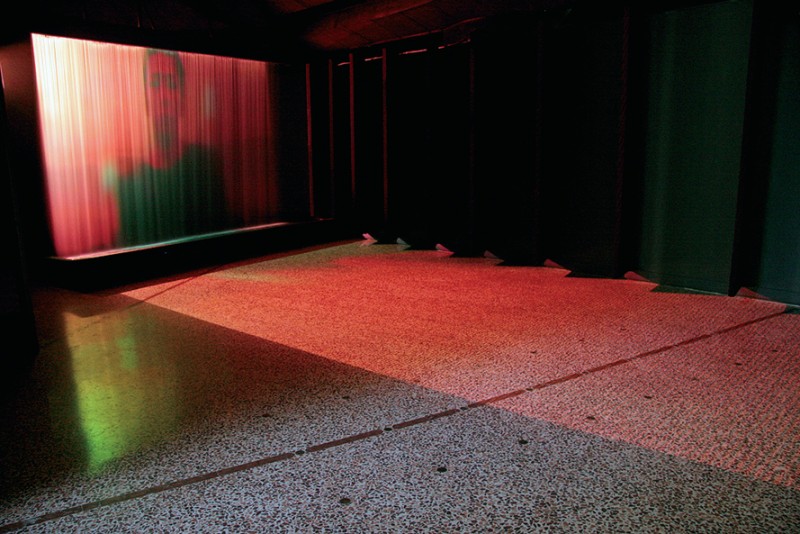

In Fountain, when I hurl the contents of the bucket and it washes the screen with blood and I stare at you from one side and you’re on the other side, I think that really is the question: how long do I have to do this? How long do I have to say, ‘Look at us and listen to us’? I think the Indigenous viewpoint in North America is often dismissed as being trivial. We’re nothing, we’re of no consequence. That’s insane. I am insisting we have a voice and a whole history, we have a point of view and something to offer. We are part of the global human consciousness. We’re not just tools for tobacco advertising and for tourism.

You have said that one of your impulses in your art is “trying to imagine where we’ve been.” I’m wondering what Fountain tells us about how we’ve inhabited that past.

We’ve always been violent and we still are violent. If you look at current politics, brutality and colonization continue to go on. So my idea is that between water and blood, we repeat all these acts against one another. It’s endless. I question how civilized we are. I question our civility.

What does this piece allow us to imagine with respect to where we’re going? Is there a prognosis?

Look at how fountains function in architectural space and how we live with water. I was in Milano at the train station and saw a fountain where the water comes out of a lion’s mouth and it’s so majestic and so powerful. So the power of water is something that we understand. Think of electricity. The United States wants our capability of generating that power for them. So I think water is power and I’m hoping that people will in some way think about this because of the work. I’ve used water a lot and I understand, respect and am fearful of it. Our mythology is one in which we came from water. And the planet is mostly water. I’m trying to deal with myself as a performance artist and as an Aboriginal woman and with my understanding of water. I grew up where I could dip my cup while I was canoeing and fishing, and now I’m here in Venice where everyone is drinking bottled water.

And you certainly wouldn’t want to dip and drink from the Grand Canal, would you? There is also the story about you canoeing around your birthplace to find where your mother was raised. You’re obviously rooted in a watered world.

Absolutely. And I think that how I deal with this notion of memory and this idea of my own Aboriginality is very conceptual, as I think it is for everybody. N. Scott Momaday, the Kiowa poet, novelist and artist—he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969—has said “we have no being beyond our stories.” I think that is great wisdom for all of us because we create our future.

Fountain, 2005, production stills. Photographs: José Ramón Gonzáles.

I’m interested to hear you mention “story” because while your work is narrative, I’ve always thought that its essential character is more poetic. You seem to go for the essential and poetry is an essentializing of language.

That’s a very nice comment. I think that poetry is lucid, fluid and open to interpretation, and that’s what I strive for in my visual and performance art. It’s not just about me or my people; it’s about offering an idea and a question to the global community and then, in turn, accepting other people’s ideas. When I’m feeling idealistic, I think that’s how we can create a better place, which we have to do. Because the world is getting smaller, we’re becoming too numerous and we’re depleting our resources.

Are you optimistic that making art makes a difference?

That’s a tough question. I fluctuate between thinking it’s a good thing and thinking it’s useless. Or about people thinking it’s useless. In the end, our society is so full of barriers and borders that I think as an artist and as an Aboriginal person I have found a way to be as free as I can possibly be. For me, art is freedom: to speak and to think and to question.

I don’t ask this naïvely, but I wonder, is your gender an even more complicating factor than your being Aboriginal? Does being a woman mean there is an additional hurdle you have to overcome?

Absolutely. I live with it in my country, where racism is a problem, and then, being a female Aboriginal, you suffer in another way. I’ve had to grow strong and be insistent and be assertive in order to survive. You can see it in the newspapers every day in Canada. It’s especially prevalent in the area I came from—northwestern Ontario—and in the prairies; it’s all my family. Native women have struggled and that’s why I live in Vancouver and why I’ve done work about those things.

You look as if you’re working extremely hard to perform the water ritual in the Fountain video. Do you recall how you felt when you did the fourth take, against the advice of the film’s director, Noam Gonick?

I was exhausted and frozen, but I was determined. I was almost in another state of mind. I think I knew I had to go there and I did it for the work. I wanted to do it another time but Noam said no. I was going for a fifth. I am a crazy woman and I can push it when I want.

That intensity has been talked about repeatedly in reference to Bury My Heart. When you say you go into a trance, do you go into a state beyond whatever acting you may be doing?

Absolutely. I never rehearse. I have a vague plan in my head, but I open myself up to all kinds of responses from the audience. I basically see it as myself doing things in front of people to try to figure out how to make something that is beautiful, poetic and visceral, and that creates a tension between myself and them. I’ve become more comfortable. I’m not actually the High-Tech Tipi Trauma Mama; I think I’ve learned to use basic elements, because that’s what people respond to. So I go out there with a basic understanding of the course I’m charting and then I just go for it. I enjoy myself in the moment. I see it as very similar to a painter painting, or somebody working with clay. It’s very much about material, and material, for me, is concept. It’s about people looking at me and over the years I’ve become comfortable in that space.

The stills from the video are very painterly, so it makes sense for you to talk about “material.”

Performance art is no different from anything else. You just employ what you learned in your first year of art college about opposition, tension, line, and then you do it in the physical, live element. I consider myself somebody who is just making visual images. People ask me what is the difference between theatre and performance art and I don’t have a good answer for them. I fall down because I just do things in front of people and try to make it really interesting.

Because the video performance wasn’t done for people—other than the film crew—was it more difficult to do?

It was, because I was working in a foreign medium with audio equipment and lots of people waiting around, and being self-conscious about that. But that changed once I started going in the water and by the fourth time, I knew I was taking it where I wanted it to go. So it’s about bending something to your own understanding of what performance art is. I was taking video into the visual as a performance artist. What happens here in the installation for Fountain is that the video is beautiful—when you see it on your television or your video screen, it’s really slick, high-quality production—but once you add the water, it’s organic and unpredictable. We controlled it as much as we could, but still it does its own thing, and what happens is that the water in the space becomes the performer and brings performance back into the edited video version, which makes me happy.

It’s a lovely notion that the water animates the video.

The water is the performer; I’m just the background. It’s weird and strange how it works, but people are responding to it in a positive way because they feel it’s visceral and primal and emotionally charged. I’m not performing but the water is performing. At two and a half minutes long, the video is very intense.

You use red and white a fair amount. It’s a palette loaded with implication.

Well, I don’t have to deal with black and white. If you look at the Venice Biennale itself and the fact that artists represent nations and our flag is ironically red and white—then you’ll realize that has worked pretty well for me.

Are you proud being there as an Aboriginal woman representing Canada?

Absolutely. I’ve had so many friends who are Aboriginal from both north and south of the border say that they are very proud and so it’s not just about Canada but about North America.

Why did you become an artist?

Because I didn’t know what else to do. I could have become a truck driver because I liked the road and the freedom of the road. I used to be a waitress in a truck stop. I think that art is freedom and truck driving is freedom.

One of the things I admire about Tomson Highway is that he didn’t know just his own culture, but also the white culture into which he successfully moved. I sense you occupy a similar position.

And to be generous in both is a good thing because it allows you more opportunities.

That partaking of two cultures is also a freedom?

I think it makes you more aware and more clever. You have to work a little harder and not get trapped. I think artists can be trapped because it’s all about categorizing and boxing people in. You have to be clever and learn how to navigate in two realities. But it can be lovely. For example, last night here in Venice, my husband, Osvaldo Yero, who is Cuban, went off with Cubans and I ended up at James Luna’s party, where we were all Indians.

In your work, you have been able to take tragic stories, like A Blanket for Sarah and The Capture of Mary March, and instil in them a deeply poetic quality. One of the dangers in living in the past is that we resign ourselves to living with elegy. Is that a problem for you?

No. In Fountain I think the whole history of colonization is told from my perspective as an Aboriginal woman and from the perspective of the women I find to make works about. It might be my time now, but I’m no different from those women; I’m just their contemporary, so if you look at the whole of Aboriginal men being driven outside Saskatoon by members of the police force and freezing to death, or if you look at Noam Gonick’s amazing film, Stryker, you see that it goes on and on and it hasn’t ended. So when I’m throwing the blood on the screen in this formal shape of a fountain and I’m bringing back the fountain to Venice—it’s like saying “colonization is a killer.” And it’s still doing the same thing in Canadian contemporary culture. My question is, when will it stop? It’s very complex figuring out what is my role as an artist and what do I have to say. I’m trying to do the best I can. I’m just here to mark things down, to make history.

And that interrogation is an ongoing and necessary process? The questioning doesn’t ever stop?

It will never stop. After the Oka crisis, I did a piece in which I strangled myself singing the Canadian national anthem, first in French and then in English. I think I could do that until I die and it will still be valid as a work.

How have you escaped rage?

I escape it through making beauty. We know that we live in paradise but we don’t appreciate it. With art, at least, you can make beauty and at the same time you can address the ugly. That’s what I want to achieve. I don’t want to get lost in something and not address reality or the time in which I’m living.

And that’s why your pieces look the way they do. Beauty is the tone that has to carry the message.

I hope so.