The Incredible Rightness of Mischief

An Interview with Kent Monkman

Kent Monkman’s revisioning of the Canadian artistic, social, political and sexual landscape is the most radical rethinking of the way our society functions any artist has accomplished in the 150 years since Confederation.

He works inside a lengthy history that regards 1867 as one kind of benchmark moving forward; he also drifts back to New France, the period 150 years before Confederation, when Indigenous peoples were major players in the fur trade that drove the North American economy. His extensive inquiry is provocative, exhilarating and profound.

Kent Monkman, Iron Horse, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 84 x 126 inches. All images courtesy of the artist.

When you see “Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience” and actually take at face value what the exhibition is telling us, you cannot be the same person coming out as you were going in. (The exhibition, organized by the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, opened in January of this year and will travel to eight Canadian cities through October of 2020.) Monkman calls “Shame and Prejudice,” which he curated and largely made, “a project.” My projection is it will emerge as the most important exhibition organized by any Canadian museum in this anniversary year.

Monkman’s view of history is the Trickster’s view. From that perspective he looks at historical events and asks the most subversive question of all: “What if … ?” What if things happened a different way and other people were involved? For him, the Trickster is “the creator who also bungles everything, who looks at the world as something beautiful but also flawed.” Monkman has included his Cree character, Weesageechak, in a specific painting in 2010 where he “teaches Hermes how to trick the four-leggeds,” but his general spirit operates everywhere in Monkman’s work.

The most disruptive and transforming figure in these reimagined narratives is Monkman’s alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, the glamorous two-spirited time-traveller who redirects the national narrative in radically different directions. Her name encourages a close hearing: “Eagle Testickle” is an approximate homophone for “egotistical,” a word that points to Miss Chief’s occasional misreading of settler motivations (she realizes too late that the Iron Horse is really a Trojan Horse, and she admits to being silenced in the face of the Indigenous children kidnapped into the residential school system). Her other name is compensatory: an equivalent hearing of “mischief,” the attitude she holds towards pretty well everything. Monkman’s description of her nature embraces both soundings. “She’s an anti-hero,” he says approvingly, “and kind of a hot mess.”

Installation view, “Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience,” 2017, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkensheid.

Miss Chief, as she tells us in one of the excerpted memoirs that constitute the text for “Shame and Prejudice,” is best when she is naked. True to form, she comes to the meeting of the Fathers of Confederation wearing only a teardrop earring and black high heels. Her presence is transformative; the Founding Fathers—she calls them The Daddies, 2016—are variously dumbfounded, angry and captivated by her presence.

Monkman is asking what Miss Chief’s attendance would have added to the fabric of the national narrative had she been in Charlottetown in 1864 and subsequently turned up in Robert Harris’s commissioned painting 20 years later. In Harris’s painting there is an empty footstool in the foreground, across which is thrown a common coat. Monkman views the innocuous piece of furniture as a stage and replaces the coat with a Hudson’s Bay Company point blanket, on which she positions her naked derrière. The iconic multi-striped blanket is a versatile prop in his historical retelling: it billows behind a pair of bow-and-arrowed warriors on horseback who are executing some form of mischief in Wedding at Sodom, 2017; it is a symbol of betrayal in The Subjugation of Truth, 2016; and in his indigenized reworking of the bull fight in Seeing Red (2014), it functions as the toreador’s cape that lures the Picassoid bull to its death. For Monkman, the ubiquitous blanket represents “the imperial powers that dominated and dispossessed Indigenous people of their land and livelihood.”

Recontextualizations of this kind are central to Monkman’s aesthetic strategy. He reinhabits earlier painted narratives and fills them with his own content. The stories come from the Bible, classical mythology and from both Renaissance and modern art history, so time frames tumble one into the other. In God and Man, No Religion, 2012, a Yeti joins Umberto Boccioni’s futurist sculpture in a brisk constitutional through a luminist landscape; in Struggle for Balance, 2013, Titianesque angels hover above street fights and burning cars in Winnipeg’s North End; in Teaching the Lost, 2012, figurative sculptures by Ossip Zadkine, Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore and Picasso are instructed in a landscape classroom that could have been designed by John Constable or Nicolas Poussin; and in Sunday in the Park, 2010, Seurat’s fancy Parisiens are replaced by even fancier Dandies.

The Dandies, the berdaches and Miss Chief are of the same tribe, and they embody Monkman’s celebration of “the plural sexualities that existed in pre-contact North America.” Their spirit is, again, fleshed out in his recent “Rendezvous” series; in Wildflowers of North America, 2017, trappers, traders, mountain men and Indigenous nations gather together in the 19th century to celebrate the arrival of spring. And Miss Chief is there as the party planner, free to tease out connections across gender and time, both of which she bends in her personal stories of libidinous intent and revolutionary content.

Kent Monkman in collaboration with Chris Chapman, Jezebel, 2017, archival Giclée print on archival paper, 16 x 19 inches, from the series “Fate is a Cruel Mistress.”

In putting together “Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience,” Miss Chief said she “wanted to activate a dialogue,” and that her “mission” was to authorize an experience that had been excluded and erased from the canon of art history. Her “authorizing” makes a persuasive connection between author and authority. She is the teller who tells the tale of power.

There is the old saw that history belongs to the victors. Kent Monkman has a painting with that name. History is Painted by the Victors, 2013, shows Miss Chief at her easel, eyeing clusters of naked men swimming in a lake. The men look as if they have left Thomas Eakins’s swimming hole to frolic in a much bigger, luminous liquid body. If the title of the painting holds true, then all the battles settler culture thought it had won are being refought. In Kent Monkman’s retelling of Canada’s foundational narrative, there is a new culture of victors. It is led by Miss Chief, and, after her mischief, nothing will ever be the same.

The following interview was conducted by telephone to Prince Edward County on June 27, 2017.

Border Crossings: I want to talk about “Shame and Prejudice.” You frame the exhibition as a story and you transpose the title from Jane Austen’s, Pride and Prejudice. How do the narratives intersect?

Kent Monkman: When I realized that I wanted to have this story told in Miss Chief’s voice, I imagined her like one of the Bennet sisters, wanting to improve her lot in life and bag herself a rich daddy. So I decided to lift the title from Jane Austen, and because it fit Miss Chief’s time-travelling, it went on from there.

She is a young woman who’s always on the lookout for something that will improve her condition. At the same time you dedicate the exhibition to your grandmother, so is there also a personal dimension?

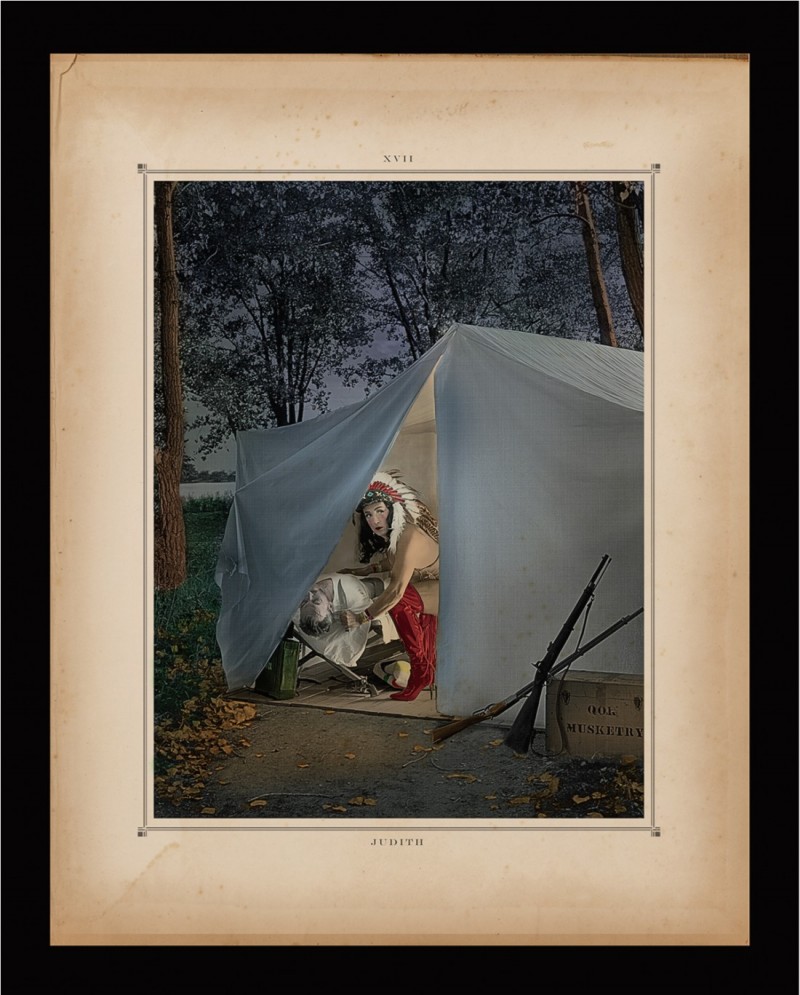

Kent Monkman in collaboration with Chris Chapman, Judith, 2017, archival Giclée print on archival paper, 16 x 19 inches, from the series “Fate is a Cruel Mistress.”

Absolutely. With Canada celebrating 150 years, most Indigenous people are thinking, what does this mean to us personally? What does it mean for our families and communities to be inside a country that has perpetrated a genocide against us? That was my main thinking about this exhibition. I tried to make it as personal and human as possible. I wanted it to resonate on that personal level because sometimes people think of these things in an abstract way and don’t connect it to real lives. I wanted the audience to connect to real people; and Miss Chief, through her didactic narrative, talks about those bonds of family and community.

Miss Chief has special powers that she can use to actually play Wolfe and Montcalm against one another with the beaver as a trophy.

Exactly, and because she’s a time-traveller, she can make historical lives seem real. That was the point I wanted to drive home. These are real lives and we’re talking about relatively recent history. My grandmother survived the residential schools but her mother, my great-grandmother, was born in St. Peter’s, Manitoba. Before it was converted into a reserve, it was an Indigenous agricultural community just north of Winnipeg, and there was an agreement that the land was supposed to be guaranteed in perpetuity. But the settlers and the township of Selkirk pressured the government and they eventually forced everyone out of their homes and relocated that community. The dispossession of the land makes a real connection. The first 10 years of her life were in turmoil because it was the time of the 1885 resistance. Because I had a relationship with this amazing person for the first 10 years of my life, I feel connected to this history in a very personal way.

The planning and the execution of your show actually coincided with the Truth and Reconciliation hearings. In your own view, how important was that process of having a people be able to speak about their experience?

Important and essential and groundbreaking. It communicated truth about the horrors that had largely been silenced. This information is now available widely to everyone and it represents a turning point because so many people had never had their stories heard before. So there’s acknowledgement, but we still have a long way to go in order to reach the next point, which is restitution. Canadians need to come to reconciliation about their own history and about what happened to Indigenous people through the colonial policies of the Canadian government.

It’s telling how powerful language is. In the epigraphs that you incorporate into the booklet that accompanies the exhibition, Duncan Campbell Scott and his colleagues in the Department of Indian Affairs talk about “the final solution.” It’s absolutely shocking to come across that language.

Installation view, “Fate is a Cruel Mistress,” 2017, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkensheid.

That’s what I wanted to communicate. Most Canadians have no idea that their country was founded on dispossession and a genocide perpetrated against Indigenous people. There is no soft language to counter the hard language of the colonial autocrats who executed these policies.

The chapter in Miss Chief’s story that causes her to go mute is the one that describes the forcible transfer of children to the residential schools. She says there’s no way to talk about it. Does that parallel your way of thinking about this particular event as well?

There has been no image in our history to communicate or to portray this extraction of children. I wanted to rely on the power of the painting to communicate the layers of emotion and horror and the depth of what that experience could mean to people, and I was relying on history painting itself. I worked with Gisele Gordon, a writer with whom I’ve collaborated for many years, and she wrote the text after much discussion about the content of each chapter. We decided that it was better and more powerful to let the images speak and let the room speak through the cradleboards.

Does the idea of the painting come first or was there a text and then a painting had to be made that would correspond to the implications of the text?

All the images came first, as did the structure of the exhibition and the curation of the objects. Miss Chief’s narrative came at the end. When I set out to create the exhibition, I knew it was going to be framed through her point of view, but I had a very loose idea about it. Then I realized that the didactic panel in each room needed to be in her voice, so the texts were drafted right before the exhibition. Gisele wrote them and was able to get inside my brain and unpack all the layers and intentions behind the work. I struggled with trying to write those chapters myself and eventually realized that it was beyond me because I’m not a writer.

Bête Noire, 2014, painted backdrop (acrylic on canvas), mixed media sculptural installation, 192 x 192 x 120 inches.