The Articulate Body

Carolee Schneemann in Conversation

Let’s get the bewildering part over with first. Carolee Schneemann is the most unfairly overlooked artist to have emerged in the United States in the last 30 years. The reasons why this enormously gifted New York painter, filmmaker, performance and video artist has suffered a range of suppressions at the hands of the art world-from outright censorship to calculated indifference- are the stuff of nasty fairy tales and power games. Schneemann is, and has always been, just too much for a world in which attitudes are predicated on notions of taste and decorum. The artist herself has quipped that “they’re afraid I’ll pull down my paints” and somewhere in that joke is the root of the problem: Schneemann is unpredictable and uncontrollable. Her recollection is, that from the crib she “decided that my genital was my soul.” Whether this is true or not is less significant than the fact that it is the origin of the profane song of herself she has been singing in a range of media since she first burst onto the art scene in the early ’60s. Her major works in that tumultuous decade -Eye Body, Meat Joy, Viet Flakes and Snows-have become legendary, as has the artist herself. The dilemma created by such a status is that it locks Schneemann in the past when her work- then and now -is so insistently of the present.

Dream activated pre-performative drawing for Interior Scroll, 1975.

I don’t want to give the impression that I’m the first critic to remark on Schneemann’s marginalization, at the same time it’s important to more clearly state what has been its nature. From the beginning she has had her champions, critics who observed that her full-frontal attack on the essential puritanism of American society was both outrageous and healthy. The praise has continued: her survey exhibition called “Up To and Including Her Limits,” at The New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, was chosen as one of the three top shows in the U.S. in 1997. In February of this year she recreated a major installation for “Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979,” an exhibition at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and will have significant exhibitions in Vienna, Barcelona and Tokyo through 1999. She is also preparing a pair of books for publication, The Body Politics of Carolee Schneemann (a collection of unpublished essays, notations and performance scripts) for MIT Press and a selection of her vast correspondence that is being edited by Kristine Stiles for Johns Hopkins. Schneemann, with characteristic expansiveness, describes her correspondence as “… a monster through which the whole history of culture passes” and I’m inclined to believe her. “Excuse my absolute freedom”- she is quoting Artaud with uncontained enthusiasm - ” I refuse to make a distinction between any of the moments of myself.”

Up To and Including Her Limits. 1973-1976, performance/ installation, crayon on paper, rope, harnass, video, Super 8 film relay.

Many of those moments have been ecstatic. In February 1964 she wrote a letter to Jean-Jacques Lebel accepting his invitation to participate in his Festival of Free Expression in Paris. She offered a “Happening” called Meat Joy, which she explained was one of several works “moving in [her] mindseye.” Her description of what her mind saw was what audiences in Paris and New York were also able to see: “Meat Joy shifting now, relating to Artaud, McClure and French butcher shops-carcass as paint (it dripped right through Soutine’s floor)… flesh jubilation… extremes of this sense.”

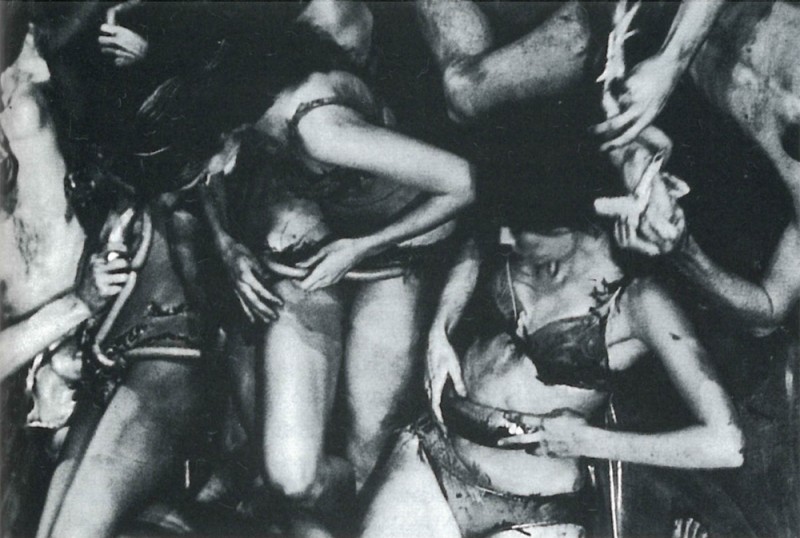

She’s got it right with flesh jubilation. What strikes anyone looking at the existing fragments of the Paris happening is how much fun the performers are having as they variously paint and smear chickens, fish and sausages over one another’s bodies. Looking at the film you can almost smell the room and you can certainly feel the visceral contact of skin on skin. Schneemann believed in the privileging of the body’s sensate and immediate experience over rational processes, and everywhere in her work (in all media) is evidence of that celebration. By the time she makes Fuses, the second in a trilogy of films produced between 1964 and 1978, she is involved in unrepentant fucking for the camera. This film has elements that are erotic and raw but they are too intelligent to be pornographic (this was not a view shared in Russia where Fuses was censored at a Moscow screening). Reading through her descriptions of both what should happen in her films and performances, and why these things are happening is a delight; Schneemann’s body was a body politic and it was always thinking. While making her fine painting/constructions in the early ’60s, Schneemann had begun to think of her body as an integral part of the art- making process both because it originated the aesthetic gesture and because it could be an extension of the painting itself. In Eye Body she enacted and documented a series of “physical transformations” in which she covered herself in grease, paint, chalk, plastic and ropes (and some snakes). “Not only am I an image-maker,” she says in More Than Meat Joy, “but I explore the image values of flesh as material.” Her inscription of the body-“marked, written over in a text of stroke and gesture”-sounds like any number of contemporary women artists for whom Schneemann is the unacknowledged leader of the pack. She is the woman who the wolves run with.

Her intention then, as it is today, was to use the nude “as a primal, archaic force” and to some degree the unapologetic essentialism of this position has squeezed her out of hardline feminist discourse. At the same time, it has made her essential to anyone who admires the body’s inescapable and dramatic beauty. Lucy Lippard is right to characterize Schneemann as “an emissary from the Goddess” who “bodes no good for the tightassed backbiting esthetic status quo” but she was also an emissary of sexual power. When we look at her friend Erró’s photographs from Eye Body today what is so startling about them is the artist’s allure. There’s no other way to put it. Schneemann was too good-looking to be taking off her clothes in the name of art, and she must have been aware of it. Certainly in her lectures as an art “‘istorian” she took pleasure in confounding the audience by asking a series of perplexing questions: “Does a woman have intellectual authority?” and “Can she have public authority while naked and speaking?”

Up To and Including Her Limits. November24 to January 26, 1996. The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York.

Schneemann has always delighted in posing vexatious questions. While they have often been cushioned in good humour, we shouldn’t lose sight of their indelible seriousness. In her most recent work, like Mortal Coils and Plague Column, she focuses on the tone of elegy that she has played, along with a full song of celebration, throughout her amazing career. The three-minute video collage called Known/Unknown from 1996 is a moving and uncompromising look at the intersections of health and disease that she loops through mind, body, nature and society. It is almost impossibly layered and every frame counts. From Viet Flakes (1965) on, Schneemann has been one of the most poetic and economic filmmakers working in the U.S. and her most recent work continues that intense, inescapable focus on issues and images that are of consequence.

In 1977 at the Telluride Film Festival, Carolee Schneemann read a counter-statement in response to the image on the film poster that was used to advertise the event. At the end she speculated about how the new erotic woman would be seen: “perhaps as primitive, devouring, insatiable, clinical, obscene”; then she took a writerly breath and added, “or forthright, courageous, integral.” I can’t speak for her on the issue of how far we’ve come as a society in realizing the eroticized woman she wonders about, but I can say with certainty that those last three words are perfectly suited to the uncommon power and intelligence of the work — and the being — of this utterly necessary artist.

The following interview was conducted by Robert Enright in August while Carolee Schneemann was in Winnipeg to give a performance at the St. Norbert Arts and Cultural Centre.

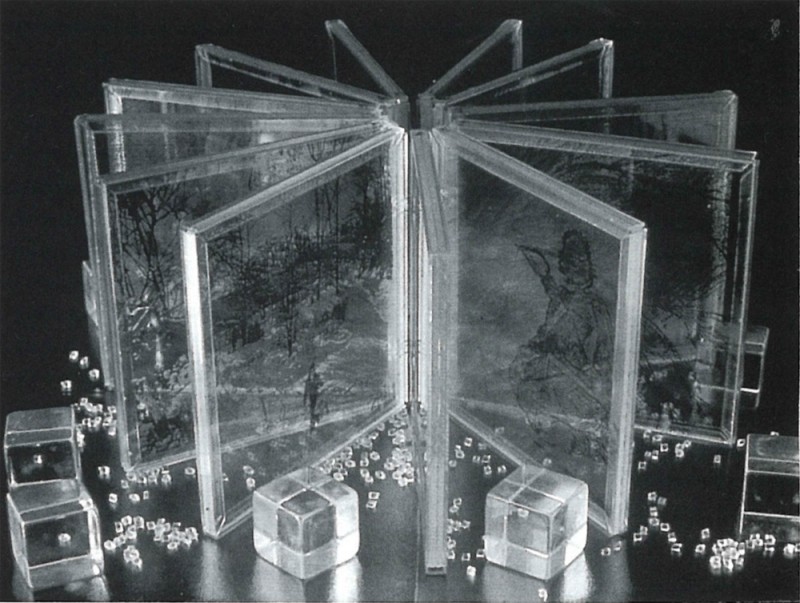

Venus Vectors, 1986-1998, plexi panels, 42” x 50” radius 6’, sculpture/installation, acrylic, aluminum, video mmonitors, 2-channel video of Fresh Blood performance, photographs on mylar.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I know very little about your early life growing up in Pennsylvania, although you have talked about a Quaker education.

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN: Well, it was a terrible, semi-rural German Mennonite world. All these sects were around — Amish and even more obscure ones that I can’t remember. My father was a country doctor and most of his work was traveling into outlying areas. My pleasure was to go with him, just to leave home. I learned to sit for a very long time in all kinds of weather, because if you got cold or had to pee, then of course you wouldn’t go along. So that was an important discipline. And as a child I was always making images, quite obsessively. It was considered something that had charm, something special.

BC: Making images was something that pleased your family as well as yourself?

CS: Yes, because they were pretty amazing. Some of the very early drawings were done on my dad’s prescription tablets. When I was five years old I became obsessed with the image as something fractured in time, so that each page was treated as a moment and it would take five or ten pages before the image came together. The first page would have a point coming in from the left, and another little triangle coming in from the right and then you’d flip the page and there’d be more of them and then you’d flip it again and there’d be two hands. And you kept going, and there’d be arms attached to the hands and pretty soon there’d be two bodies face to face.

BC: You were five when you were going through this process? You must have been precocious?

CS: But my family didn’t know I was precocious. I was the eldest of three kids, and there really wasn’t any precedent for having an exceptional child. And I was exceptional in odd ways. I was a very easy, angelic child and then I developed into what my father, in despair and aggrieved anger, would see as this conformist non-conformist. I began to seem dangerous once I was 11 or 12 years old and wouldn’t stop drawing. You know I cleaned the house, I did everything I had to do and then I had to be alone. I would disappear into trees with all these pieces of paper and crayons. I just had to make images or I would feel very bad. At one point when I was 12 I took my babysitting money, got on the suburban train, and went all the way to Philadelphia and wandered into the museum. I don’t know quite how I did this but it was just like falling into a kind of heaven. I couldn’t believe it. Nobody bothered me and I just wandered around these long, long corridors. On dark walls there were angels and Christ figures and still lifes and landscapes. And then I got into the basement following the intoxicating aroma of turpentine, until I came to rooms where people were putting colour on cardboard and canvas. And I remember feeling that I would just expire with ecstasy. I hovered by the door listening to a man teaching his class. He told me to come in and asked what I was doing. I said, “I just wanted to watch,” and he said, “Why don’t you sit in the back, I’ll bring you some crayons and a piece of paper.” It was all grown-ups and I don’t know exactly what I was doing. At one point Blackie (Morris Blackburn}—that was his name— interrupted the class and said now everyone come here and stand in a circle, I want to do a demonstration. And he took a paper bag, shredded it up and threw it on the floor. “Now this is a Gestalt,” he said, “I want all of you to think about this and tell me what you see.” The grown-ups looked non-plussed. I stared at it and said, “Well, it’s about how everything fits together and those little pieces are all exciting to each other.” He was so thrilled he let me come back.

BC: That’s a formative moment; the fragment, collage and tearing, and the recognition that out of these pieces things could be made. It’s what Joyce would call an epiphany.

CS: There were several. My parents had a friend who was a commercial illustrator, which they thought was an artist. When I was nine or ten he bought me a big packet of coloured pencils and a razor blade. My parents said, “We don’t want the kid playing with razor blades.” And he said, “This is a tool that she has to learn to use.” So I was taken into the arcana of the pencil that could only be sharpened with a razor blade, so that you made four cuts and you had the narrow edge and the flanged edge, and that’s how you could shade and make a good line. I did perfectly horrible drawings with these beautifully trimmed coloured pencils. At one point other friends of my parents said she’s exceptional and she’s having real trouble, she can’t do arithmetic, she can’t do long division. She should go to a different kind of school. Public school was a nightmare, with disgusting little white-faced, sweaty boys looking at National Geographic and shrieking over the naked nipples of African women (I was constantly horrified). And tying girls to trees in the autumn and piling leaves around their feet and setting the leaves on fire. That was a local game. They’d only pick on someone who wasn’t okay, like Mary who had a neck injury and whose head was always on her side. I had a deep sense of being embattled with the evil masculine. Anyway, these other friends made an intercession at some point and suggested they send me to a small private school. I remember a terrible battle about it because my mom needed a coat and her friends were saying you can get a coat later. So I’m taken to a small special school, which is also the school that Noam Chomsky went to. It was run basically by an older woman with braids around her hair named Rose Wachter. The school had three grades—six, seven and eight. We had English for four hours a day. The day began with us sitting in a circle, like at a Quaker meeting, with Rose reading a poem from Tennyson or Wordsworth or Dickinson. And then you had to write and read something twice a week. It had to be something that you saw, something that you thought about, something that you looked up. It could be less than a page and then you had to stand up and read it. So we were constantly thinking about listening and about words and language. The punishment if you didn’t bring in your writing was to be sent outside in the woods to play: a pitiful solitary figure, alone with the balls and the swings outside the window.

Known/Unknown- Plague Column, 1996, installation detail, floating oranges with hypodermic needles, mirror, glass balls.

BC: Your father was German and your mother was Jewish. That’s a pretty interesting combination.

CS: It’s an American combination. My father is very optimistic, idealistic. He could take these odd risks without believing there might be consequences that would complicate everything terribly.

BC: How did you develop such a ferocious clarity about the value of the body in that world? Was that something you actually had to develop and work at yourself?

CS: No, I didn’t work at it at all. I was very lucky to see that my sense of physicality wasn’t interfered with. For a female child it was always a set of narrow escapes. I had a very anxious, suppressive mother and all I wanted to do was defeat and rebel against her. But I realize now that she protected me. Many of my other friends weren’t protected and were abused by fathers, uncles, brothers. And in counter-distinction to my mother I was peering through the keyhole into my father’s office and seeing him with ladies with their legs in the air and asking them things that I knew were really important. Like when did you last menstruate, whatever that was. And then I would sneak in the office to dust the surfaces and look at all the bottles and jars and pills and books that had body parts in them. Then I worked on the farms and did artificial insemination. When the pigs were castrated girls weren’t allowed to be near, but you could hear them screaming and all the guy jokes were heavily sexualized. If you were mowing and haying in the field all day long you just jumped in the river. Nobody was thinking about what sex you were. You were red and stinging with the heat of the hay on your skin and in your nose. And you looked at each other like lively exciting animals. When people weren’t like that it was always so bewildering. I remember I met a five-year-old Catholic girl who informed me that she peed from under her arm. I wanted the physiological proof, so I squatted down and said here’s how you pee, from in there. She just kept shaking her head and saying that’s not how she did it. That early mystifying denial of the body is indelible for me.

BC: At any point along the way did you decide you wanted to be a painter?

CS: Always. I was always in contention with the teachers but some of them adored me and helped me. There was a drawing teacher at Columbia named Andre Racz who would take me back to a garage where he lived. He was Hungarian and he lived in this glamorous garage, and heated his place with an iron stove. There were drawings everywhere. He never made a pass at me or anything, he was just my best friend. And I drew from life five or six hours a day. I wanted to be saturated with form, I wanted to be able to see acutely, so that the information between hand and eye would be immediate and accurate and true to its complexity. One day when the model didn’t turn up I could see her anyway. That’s what I had been wanting to find. I also took some very obscure courses in art history. That was an adventure. At the New School I took Greek pottery, taught by two German Jewish immigrants with fascinating accents. And, of course, New Criticism and the seven levels of ambiguity were being taught at Bard College where I had a scholarship. It was very strong on literary issues.

BC: You could argue that New Criticism-with its attention to a close reading of the text-was the literary equivalent to what materiality rep- resented in the visual arts.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions, 1963, Action for camera. Photographs: Erró.

CS: There was that sense of the word and the phrase as active objects. I was most influenced by that sense of active metaphor; how it led into realms of association which would be determined by the formal apparatus of the moment. It was also the moment when an archaeology of image and word was current, the kind of things Charles Olson and the Deep Image poets were involved with. I had become very involved with these poets.

BC: Did you know Creeley and Olson, or were you just reading them?

cs: I went to meet Olson on a pilgrimage because his work was so important to me. I built a big piece called From Maximus to Gloucester. But I have to give you the irony, too. Jim Tenney and I wrote a collage letter to Olson, a humble appreciation, hoping that we could go and meet him for my 23rd birthday in October. And we get a note back saying come on along, ‘so we drive and drive and get to Gloucester. Now Olson was immense and he’s in this small, cramped apartment and there’s an easel in the corner. He says his wife is a painter, but when I go over to the paint brushes they’re totally dehydrated and the turpentine is evaporated. It looks like the same old thing; she has to be devoured so that he can flourish. But he had this little grin on his face the whole time — and he brings us in to his tiny studio, and there on the wall are blown-up maps of Gloucester. And he says to Jim, “It’s very good that you’ve come back to your source.” Jim looks a little bewildered and Olson says, “Well, look right here. Here’s the Tenney Graveyard, the Tenney Path, here’s the old Tenney farm homestead.” Jim’s ancestors had landed in Gloucester in 1618 or something and his progenitors went west and ended up as Mormon dirt farmers fighting Pancho Villa. The ones who stayed east owned most of the Massachusetts coast line. Olson is researching all this and here comes Tenney walking into his own lost history. But let me tell you one more thing about Olson. Like many huge people he’s a gentle giant. He doesn’t want to hurt anything, but he’s extremely hurtful to me in a way that becomes one of the early contradic- tions where influence is toxic. We were walking along the beach together and I’m gathering lobster traps and debris and carrying it along, and he asks me what I do. I say that I’m a painter but I’m going to use space as time. I’m going to put things in there that don’t necessarily belong. And he said, “What, even speaking?” I said yes, possibly even speaking. And he said, “Well, just be aware that in the history of the Greek theatre, when the cunts began to speak the meaning was ruined.”

BC: Was that meant to be deliberately hostile?

CS: No, it was a friendly paternal piece of advice to a young woman. Just be aware that if you really imagine you could do such a thing, that you’ll mar it, you’ll mark it.

BC: The painting that you named after him is quite beautiful. Was it done before or after this encounter?

CS: After. But I’m not responding to that implication, I’m doing a beautiful painting and remembering that wherever I go, there’s going to be more danger. Why did he have to tell me that? I’d already been reading de Beauvoir— this is 1962 or 1963. I read The Second Sex and it was a revelation for me. I’d read Artaud and that was provoking the direction of the work. Jim Tenney and I had been reading the writings of Wilhelm Reich, trying to understand where the malaise locates itself.

BC: You’re reading Olson and Creeley and you marry a composer. So music and performance and poetry are all part of your intellectual apparatus by this time. W as that an accident or because you were interested in an aesthetic commingling?

CS: It’s just an historic moment. Jim Tenney is born in Silver City, he grows up in Colorado. In high school his best friend is Stan Brakhage. He writes the piano music for the first Brakhage films. I mean they’re kids. Tenney and I meet in New York the year that I’ve been kicked out of Bard. It was just pure, perfect recognition.

BC: You’re in two of Brakhage’s early films, aren’t you?

CS: Yes, and we’re very close with Carl Ruggles, I become Varese’s secretary just to keep us from starving when we move to New York, because Tenney wants to study with Varese but he can’t pay him. So Varese looks at Jim’s scores and I have a job. Varese was called “Goofy” but he was this incredibly sweet, dignified man. And there was a man who was not a misogynist. He had a wonderful wife. And I meet all these immense historic figures. Ian Hugo, who was the husband of Anais Nin, and of course Ruggles, the composer in Vermont. He’s an old man and he tells dinner party stories about Strauss and Stravinsky and Schoenberg fighting in an elevator in Hollywood, going to Lady so-and-so’s dinner. We were getting critical historic lessons about how work survived and how these artists sustained their lives. It was usually through rich women actually; that’s one of the lessons. But we have this nexus and there’s a moment I remember when we’d sit down and argue over a bowl of spaghetti that Jim would be the future of music, Brakhage would be the future of film and poetry and I’m the future of visual art and movement. We’d be teasing but it was something we were really thinking about.

BC: Were you paying attention to what was occurring within the combined areas of the Happenings and what the Fluxus artists were doing?

CS: I didn’t know about it until I was in the University of Illinois and I read about Kaprow’s work. So I wrote him a letter care of a gallery and it got to him.

BC: You wrote letters to everybody, didn’t you?

CS: I was shy. I was scared to do these things but I was so isolated. There’s nobody there and there’s no way out. Just fields of corn and then empty fields of ice the rest of the time. So Kaprow sends a letter back, and says, “Sure I’ll be happy to meet you. During the school break call me.” So we met in a delicatessen on 8th Street, very exotic. And he says the immortal words, “Well, kid are you buying or selling,” which perplexes me forever. Buying or selling. I’m used to Brakhage, to Olson, to Joseph Cornell, to Varese, to all these people who speak in metaphors of the spirit.

BC: Do you know what he meant to this day?

CS: He meant do you want something from me or are you going to give something to me. But we had a conversation where we ended up having a fantasy Happening, in which we would invite the audience to an ocean event and they would all go on this barge. We would row out in the middle of the ocean, then we’d cut the cords and we’d row back. That was the piece, our first idea for a collaboration.

BC: Had you seen any of the performances that Yoko Ono was doing?

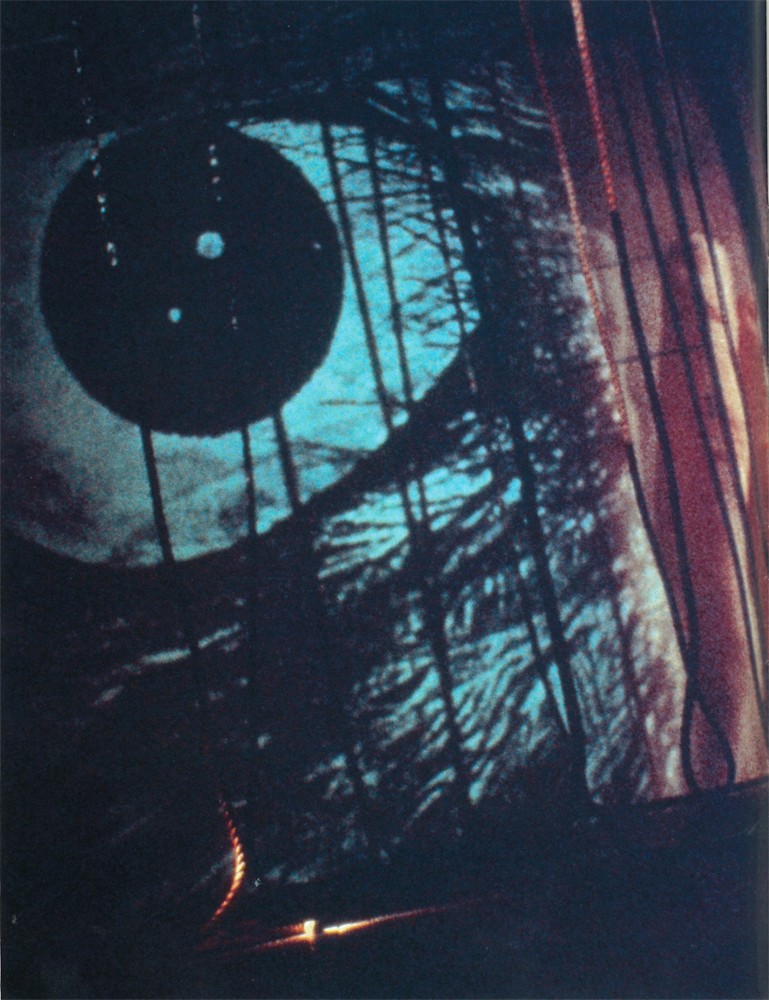

Snows, 1966-1967. Performance detail, Viet Flakes, 8mm film.

CS: I did as soon as I got to New York. She was in the Avant Garde Festival that Charlotte Moorman organized and I’d become very devoted to Charlotte. She needed a lot of help and I helped sometimes, although not as much as she needed. No one could. Then Nam June Paik arrived, not speaking any English, very charming, always smiling. He just wandered around doing odd things like slitting off John Cage’s tie and then sitting back down in the audience. There were just a lot of crazy, interesting experiments happening. I started working with a group that would become the Judson Dance Theatre and in a matter of moments after arriving in New York Jim was at Bell Telephone Labs as the Experimental Composer-in-Residence. It was a miracle he got this job.

BC: You knew Cornell didn’t you? Did you write a letter to Cornell, too, as away of introducing yourself?

CS: Cornell was on the prowl for nubile innocent — looking young muses. And Brakhage said, “You’d be perfect. He pays four dollars an hour and he might give you a job sorting his papers or something.” And in those years I was a dog dryer and an extra in porno films. I’d hold a cocktail and stand around in a tiny dress. The hard work was done by serious young women who wanted to be porno stars. The extras never got in the bedroom but we got fifty bucks. And I taught Sunday School.

BC: That’s quite a combination; acting in porno films and teaching Sunday School.

CS: Yes. All that was happening when I went out to meet Joseph in Utopia Parkway.

BC: Did you know his work before going?

CS: Somewhat. But Cezanne was always the force field that was pushing me optically into the fractured plane as an event. Then the overall field of energy becomes completely physiologically determined with Pollock. If you don’t look in a muscular way you’re not going to see Pollock at all. You’re nor really going to read de Kooning. It’s de Kooning’s dimensionality of the fractured plane coming right out of Cezanne that’s really activating how I’m seeing. I’m thinking about the frame of energy.

BC: When people look at these paintings you were doing in the early ’60s, they must have been trying to find the antecedents; here is Cornell , here is Rauschenberg, here’s de Kooning. Did you consciously decide that you were going to use your body in Eye Body as a way of extending the painting because you were tired of your work being read through someone else’s vision?

CS: Yeah. First I use machinery. The one thing the guys haven’t done at this time in 1962 is to motorize, to take the energy of the pictorial surface into actual literal movement. I’d already done pieces on wheels when I was in Vermont. I was working to music all the time and working out before I painted so the energy of my body was completely connected to the stroke.

BC:It’s the beginning of the process for you, isn’t it? The body being energized before you begin.

CS: Yes, but you can go back to the four-year-old girl who drew all these ice skaters and things falling through space. They’re dancing - there’s a lot of dancing. I motorized the pieces and the literal motion of the objects and the painting constructions opened the way for the body to interact as another actual dimensionality.

BC : It’s interesting that you would have come to the body activated in space by way of technology, when in Snows you build the film around an agrarian society’s resistance to a technological society.

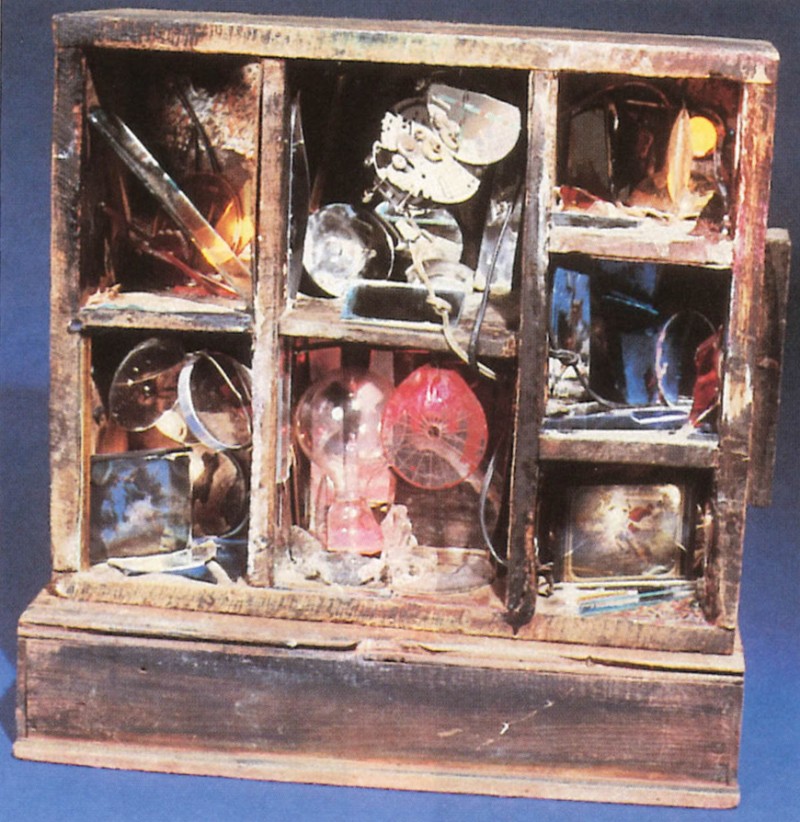

Pharaoh’s Daughter, 1966, construction in box, motors, lights, slides, 20 x 19 1/2 x 10”.

CS: Right, the technology in Snows is driving the whole piece. The audience’s seats were wired with SCR conversion signals, so it was highly technologized. That was a collaboration with Bell Telephone Labs. I have all these complex electronic switching systems working and it will be slowed down or speeded up depending on the motion of the audience in their seats.

BC:I remember reading a review from The Village Voice of that piece in which the critic is astonished by the beauty of the Martinique Theatre and the way you designed it. He describes it as if it were a painting in three dimensions. You’ve described your performances as “exploded canvasses.” I gather painting has always been at the core of what you’ve done and continue to do?

CS: I’m trained as a painter. Also as a landscape painter where everything is constantly changing. So what does that mean for me? I’m part of the weather, I’m part of every momentary shift, of flight, of wind, of aroma. I wanted to paint in rain; I would paint in snow storms. I wanted to be enveloped by what I was seeing so that there was less separation of me from it, and yet at the same time I realized being optically perceptive means that you have to hold the larger form and how it’s changing at all times, as well as be able to respond to the smallest units of change. That’s how I run my home and my studio and my teaching and why everything I do is in proper proportion to what’s needed. It all comes out of sitting like a cat waiting for the spider to give birth. Just watching and paying attention.

BC : A couple of nights ago, after your performance in Winnipeg, you said you were nervous because you don’t like to be in front of people. Now you’re known as a woman who radically broke through in the area of body and performance art. When you first decided to use your body, was it natural and easy for you?

CS: The first works I choreographed at the Judson Dance Theatre Group. I would have a mask, a whistle and a stop-watch and crawl on my hands and knees on the perimeter of where the actions I had released were happening. I was afraid to stand up. I was only able to go into performance because I had to teach people the posture, the energy, the presence, the interrelationship of what I had seen visually in my drawings. So the drawings forced me to perform.

BC : But you did it with some degree of anxiety I assume?

CS: Yep, but then it turned into an immense, ecstatic, overwhelming experience. You don’t know what is happening or where you are and you’re using everything you’ve got. The way a long-distance runner runs or a singer sings. When you go into that material, it’s magical, and as close to an ecstatic ritual as this culture can get.

BC: In a conversation you have with Amy Greenfield at the American Film Archives, you refer to the transformative power of performance, and about the incredible energy that it generates, especially if the performance is in the nude.

CS: She and I both knew that. And it raises a whole other issue about the power of the body and permission to make explicit things that are suppressed and contrived in this culture.

BC: I’m intrigued by how you arrived at that sense of self-permission. You talked about how debilitating it was when you modelled for painters because of the conventional poses of modesty and chasteness you were obliged to assume. Even when you were modelling nude, the male gaze was not inquisitive. It sounds like you wanted to go further but were being constrained even in your nakedness.

CS: That’s right. Maybe the first self- portrait I ever did was at Bard, as a freshman, in front of the mirror with my knees up and my legs open. I’m going to give you the whole thing whether you want it or not. And it wasn’t just the gaze but the control of propriety. There were these strict delineations of decorum. Of course, the male models couldn’t have that, they had to wear little jock straps or be completely naked. But the fact was we were absolutely forbidden to open up our legs because we would lose decency. Although as soon as you put your robe on they were trying to get between your legs in the back room.

BC: So you had no difficulty using your body as an instrument? Nobody else is really doing what you’re doing. Yoko Ono does her bag piece, but the sexual activity inside — if it even happened — was done covertly. And even in the piece where her clothes are cut off, it’s still a relatively modest moment, although a terrifying one. I’m sure that an event where a woman is the subject of real danger must have been alien to the things you were doing in your celebratory pieces.

CS: It’s not alien at all, it’s sister work. It relates to the man coming out of the audience in Paris and trying to strangle me in the middle of MeatJoy. I had just done some very vigorous interaction with my male partner and we ended up at different parts of the space. Before I could go back in this crazed man came at me and he had his hands around my throat. I couldn’t speak or move and there was all the chaos of the performance going on. And I thought I’m going to be murdered in the middle of this erotic, celebratory performance, and no one will even know what happened.

Meat Joy, 1964. Performance: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, rope, paper, scrap.

BC: Because the audience thought it was part of the performance?

CS: Yes. Fortunately two women in coats who were just on the edge and not into it, turned and saw what was happening. I was looking at them and struggling to get his hands off and they came running over and banged on the guy, slapped him and pulled him off me. I was saying thank you, thank you, in French, and then I went back out. After that I always had women holding little staffs with ribbons on them and they were trained in how to control the people who went crazy. I have a recent work called Ask the God- dess which I did for the first time in Canada at Owen Sound, six years ago. I keep developing this performance because it’s the only way to concentrate and release the suppressions and taboos that are still latent around femininity and genital sexuality. So Ask the Goddess is a work that risks putting myself in a position where the audience can ask me anything they want about the body and sexuality. And in order to inhabit that guise of availability and responsiveness, I feel exposed in a way that terrifies me. I wasn’t terrified when I performed it initially in Canada, but subsequently I’ve felt that I might be murdered. I’d go around feeling that just because of one maniac in New York City, you could be raped, you could be shot, you could be chopped off. So there are times when I internalize the rage, fury and repulsion that’s in the psychosis of the male sexualized imagination; times when I’m so aware of it that I can hardly move my knees. Always before a performance I have very bad physical symptoms, I think there’s something wrong with me and then my mind says it’s okay, it’s just taking all your energy away.

BC: How have you been able to maintain a healthy sexuality given that relationship with the male world? Is it because you understand that there are various degrees of male sexuality as well? Part of what’s been so remarkable about your work is its pervasive sense of joy and intelligence.

CS: I guess I’ll do anything unconsciously that I have to do to preserve, discover or nourish a stable, loving, sexualized relationship. I really have to have a partner so I know who I am, to be able to let the work go out in its riskiness.

BC: I want to go back and talk about MeatJoy because it’s such a significant piece. You must have been aware of Yves Klein’s performances in which he used women as paint brushes. Was part of the dynamic of your work a response to the female body being used as the instrument of paint-making by a male?

Meat Joy, 1964. Performance: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, rope, paper, scrap.

CS: Constantly, I mean Fuses was a response to Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving, where instead of the woman giving birth, the camera gives birth. Once again the camera is the higher agency. So I wanted to position the fuck and have the camera’s eye be my eye. The question was will this look different, will this be different? Yes, it’s incredibly different. I didn’t know that at the time. With Meat Joy I was looking for a way to somehow bring forward the suppressed unconscious sexuality. And out of my own pleasure. It’s got to come out of that ecstatic strand that you find aspects of in popular music, where the body is allowed to move expressively in the culture. So ritualized dance forms — square dancing and country-dancing — are very important early influences for me. Because everyone is allowed equal public pleasure. Those dances are so stylized; you start with your partner, then you lose your partner eight times, and you do everything equally with each other’s opposite partner and then you return to your partner. So all morality is in place, and you still have these repetitious, ecstatic little pleasures through the group.

BC: You’re not suggesting the square dance as a paradigm for group sex are you?

CS: I wasn’t thinking of it as group sex but just for the body in heterosexual, acceptable high pleasure. We don’t have anything else. But I it is ancient; maybe it used to be the dance they all did together after group sex.

BC: There is a point in Meat Joy when the paint comes out. The men paint Egyptian, linear faces on the women and then they paint their bodies. Your description of it is that they paint “thoughtfully.” The women put up with this for awhile and then they grab the paint cans and throw paint on the men. That seems to be a direct response to what Klein had done.

CS: But the first painting sequence in Meat Joy is when my partner yields to being knocked over. He’s knocked over on the paint table and laid out like the Maja, and I paint all over his body very slowly. I create him out of my brush strokes.

BC: So, the woman does the initial painting then?

CS: The beginning of painting.

BC : What was the history of your being invited to that performance festival in the early ’60s in Paris?

CS: Erró was the Icelandic painter who did the photographs of Eye Body. I was in love with Jim Tenney and lived with him but I had this enchantment with Erró based on two things. One: his aroma, he smelled absolutely intoxicating, and two: he had a wife who was a painter and he was completely for women. He was like this really good buddy and I could trust him. He had other girlfriends and his wife in Paris, and we did wonderful work together.

BC : Were you lovers?

CS: Just for awhile. I used to get obsessed with all these different guys and being lovers was a way to understand who you really were. That was part of a life-long research; you had to put your body where your thoughts were. And he said, “Lebel is having this festival and you just have to go.” So I sold a beautiful, important painting/construction to Arman, which subsequently was destroyed in his house. I have photographs of it. He paid me exactly the air fare on Icelandic Airlines to go to Paris — $150.00 — not any more or less. I was at the beginning of being a stupid jerk about money. Then my father said he would help me and he gave me a whole package of money from Martinique. So I arrived in Paris at 2:00 o’clock in the morning with a pile of money from Martinique. I couldn’t speak French, the money was all wrong and Jean Jacques Lebel hadn’t known I really was going to turn up.

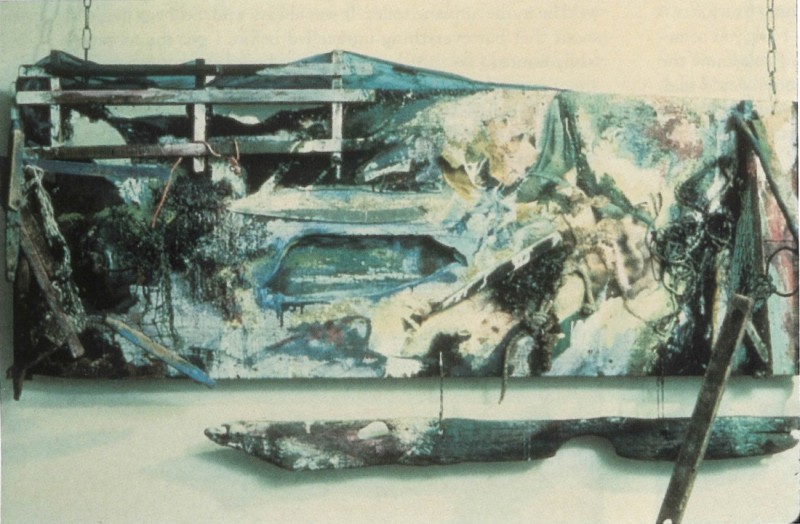

Maximus at Gloucester, 1963, construction on board, paint, photographs, fabric, lobster trap, nets, glass, 29 x 73 x 15”.

BC: But you had described the piece you wanted to do in a letter, so he knew what Meat Joy was?

CS: Potentially. Then I had to find people and make rehearsal time and he said he would help me. And he put me up in La Lousianne which was fabulous. And I became very close friends with the widow of Yves Klein. That’s who took care of me. She was a young woman, barely older than I was, and I hung out at her house. She found me my lovers. What do you need, do you need something to eat, do you need a lover? I’ll lend you a sweater.

BC: Oh wow, a pullover and a lover,I guess they amount to the same thing — something warm and woolly.

CS: No, they don’t amount to the same thing at all. Not at all. I can do without the sweater if I have to.

BC: You’re so outrageously open. How did you become that person?

CS: A woman with a declared sexual appetite is still very shameful.

BC : Were you made aware that what you were doing was transgressive?

CS: Yes. Because people kept trying to stop me and I was obviously only doing the right, good, next useful thing. Everyone definitely wanted to know about this. And then they’d censure Fuses and they’d take my work down off the walls.

BC: When you were making Fuses I thought there was a cameraman involved, but there wasn’t.

CS: No, that’s the most important thing. I used a wind-up Bolex.

BC: Thirty-second intervals and then you’d have to reload?

CS: Well, we wouldn’t reload. We’d just keep going, the camera would run down and then when we were ready we would wind it up and do something else. That was hard. I remember weeping over the sink doing the dishes one morning and Jim askihg what was wrong, “Well, I really don’t want to go back to bed and do some footage of Fuses,” I said. “It seems so mechanical but it’s snowing and the light’s just right.”

BC: Fuses seems an attempt to work through an iconography of the body in film. The postures and the gestures are those you could see in everything from hard-core pornography to romantic films? Were you conscious of trying a series of styles? In looking at it now a vocabulary of erotic film actually emerges from it.

CS: I just wanted to see what the camera would capture that would look like the ordinary things we did. Some of them I couldn’t get very well. I never really got a beautiful cunt shot in Fuses and I’ve been working on that ever since. We didn’t have good close up lenses.

BC: So it was a personal, autobiographical domestic film?

CS: Domestic is what it’s about. It had to be ordinary. That’s why there could be no other person shooting, that’s why the camera was treated the way women are treated in porno films. The camera was tied up to a light fixture; it was kicked off the book stand.

BC : So technology takes a back seat to intimacy?

CS: Absolutely. And that’s what makes it all desperately driven because I’m always thwarted with my technology. Nobody came forward with the right lenses, the right camera, with the right tripod. And half my film stock was offcuts from people. I never knew who would be all orange or green.

BC : Were you aware while making Fuses that it could cause trouble?

Mortal Coils, 1994-1995, multimedia installation, 4 slide projector units with motorized mirror systems, 17 motorized manilla ropes, “In Memorium” wall scroll text.

CS: Yes and no. Yes, because film was being confiscated. Anything that had erotic content could be confiscated by the FBI and you could go to jail. And the film labs would be heavily fined and closed down. So even with my pitiful hundred-foot reels I would go trembling into the lab. I didn’t know this lab had a porno factory in the basement. All I knew was that I was told these two guys, Vinnie and Frank, would print my film for me. They would do 100 feet as it came through. After I’d been doing this for two years, Vinnie, the shy one, says, “Uh, Miss, can I ask you something?” And I said, “Sure Vinnie.” And he said, “You know the blue part. Does she like what he’s doing to her there?” And I said, “She likes it very much, otherwise she would have asked him to stop.” And he says, “But if I came home and tried that on my wife, she’d say, “Vinnie, where the hell did you get that idea?” And these guys have got a porno lab in the basement! They’re gangsters. It’s so cute.

BC: The intriguing thing about Plumb Line, the sequel, was that it seemed a more radical film than Fuses. The way you handled the subject matter is actually romantic; it’s got shots of the couple in the basement; there are bathing suit shots; there are romantic running shots. Relative to the way the content is treated in Fuses, it’s the difference between hard-core and something positively romantic. Was that a conscious choice to shift the reading of domestic experience in that second part of the trilogy?

CS: Plumb Line is a beautiful structure but it’s just layers of failure within a film. I didn’t get the footage I wanted. It was going to be the really hard-core sex film. It was going to be an unimaginable extension of the sex in Fuses. Because the erotic relationship with the man in_ Plumb Line_ was extreme. I mean sex was his gift. It was a relationship that was very mystifying because it was such an intense and daunting sexual communication. I had naively believed that everything else in life would form in harmonious proportion around it. But I had never been with a diabolical fiend before, and this was a diabolical fiend of a man.

BC : In every way, or just sexually?

CS: In every way but sexuality was his real expressivity. And that’s where his real power was. Once we were in bed I couldn’t even wind the camera up. We wouldn’t be in bed; we’d be under a table; we’d be behind a shrub, we’d be in the back of somebody’s car, we’d be in the airplane toilet. It was always wild. So I was going to shoot that but everything unravelled before I got the footage I really wanted.

BC : A phrase you’ve used about your experience in the ’70s was that you “flipped out.” What happened?

CS: Anybody really sensitive seems to have flipped out by the end of the ’60s and early ’70s. The Vietnam War had been driving all our transformative energies. It never ended. We never stopped blowing up these other people and our own selves and lying about it. And towards the end of the ’60s, our major political figures had been assassinated. I was in bed with the Plumb Line man and you could hear the city of New York blowing up around you. I could feel screams in the air. Couples left each other, communes broke apart, people were fleeing to Canada, guys who hadn’t already left were giving everything up and moving to Europe and Scotland. There were spies everywhere, phones were tapped and mail was opened. Political actions were stopped before they were started, even when there were only three friends involved and no one had spoken on the phone. This country was polarized. Today all the codes of appearance are completely mixed up, but in those days if you had a ring in your ear and hair below a certain level stones might be thrown at you or you’d be in a diner and some guy would try and put a fork in your hand because you looked like a commie pinko-dupe. It was constantly volatile and potentially violent. And I was teaching everything I had developed, from Kinetic Theatre to action resistance in the streets, so we could work as a group instead of being mauled by the formations the police had determined would be effective against a milling, open group. But the break came when I split up with Tenney because he was the bedrock relationship of my life. He had been a companion, soulmate and partner. I just fell apart.

BC: But you were able to piece yourself back together. A different kind of collaging had to go on.

CS: It wasn’t like piecing together, it was like a slow coiling of some material that re-integrates itself.

BC: Yet out of this you made Viet Flakes, which seems to me to be one of the most effective indictments of the Vietnam War ever made.

CS: It’s a great help to hear you say so.

BC: The soundscape was very effective. None of the melodic or lyrical lines come together except when you get through the piece.

CS: I wanted to pick fragments that characterized this historical period, including Vietnamese chants and religious music, but to have it so fractured that it could not be a coercive narrative. It could only be cumulative. I had a good camera, but again I didn’t have close up lenses. I was in a state of the most immense formal desperation. You know what it’s like when you don’t have your equipment.

BC: Snows gets pretty ferocious. Was that a reflection of your anger at what Vietnam represented?

CS: Completely. We were outraged because we belonged to a culture that had this gratuitous violence.

BC: Did you consider Snows a major breakthrough as a political statement? Today it seems remarkably powerful.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions, 1963, Action for camera. Photographs: Erró.

CS: Everything is such a struggle that you don’t know if it’s a breakthrough. You just have to do it. And the magic that was happening with it was incredible. The owner let me have his theatre, and he kept it dark for 10 days so that we could build this crazy stuff. I wanted to build a complete snow environment.

BC: Did you want it to be beautiful?

CS: Oh yes. It had to be breathtakingly beautiful, embedding all this horror. But here’s what happened. I went to Gimbel’s at Christmas and asked if I could have all these snow branches. I found the Decoration Manager, and he said by law we have to destroy everything. So along the way I met one of the minions and said, “I’ll let you come see this piece if you call and tell me when they’re throwing everything out.” Which he did. And a whole bunch of us ran there and we were carrying all these huge white branches and it was snowing on the snowy branches. I took them into the theatre all wet and covered with snow and began to build. And I would dream stuff. For Chromalodeon I had a dream where I needed a whole box full of velvet ribbons-blue and magenta and rose. And they were out there in the morning.

BC: Has dream played a role in your work a fair amount?

CS: It’s all dreams’ fault. I have nothing to do with anything I’ve ever done, it’s all just dream-sent. I’m innocent.

BC: You said something interesting about one of Jim Dine’s performance pieces that you saw-in the ’60s in New York.

CS: It was a solo where he sat alone and did very limited movement within the space. He concentrated the space as if you were in his unconscious and then he made some lateral motion. It was a piece about his encounter with the deforming, reconstructing power of the father. And it was certainly the first time that a male artist dealt with suppressed taboo. It was real stuff. I was very moved, very heartened and then shocked to hear the reactions of our friends, particularly the men who thought it was the worst thing he had ever done, that he had put himself in a stupid corner, and that it was bad work. I knew they were lying. But I’m very happy to talk about it with you because this is the sense I’ve carried with me. I haven’t spoken about it since 1965.

BC: Was your experience in New York in the ’60s pretty exciting?

CS: It was thrilling. You felt you were on this rising crest of energy and change and determination. We were all suddenly interconnected and there were only about 300 artists. You could invite Cage and Cunningham to your first performance at the Living Theatre on their dark night and they would be there. At the first party I gave in New York — Oldenburg called it my debutante coming out party — Whitman was there, Oldenburg was there, Dick Bellamy, Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti, Bob Morris, all the musicians, Philip Corner, Malcolm Goldstein. Some Fluxus types. It was wild. And Neil Welliver and Chamberlain got into their usual fight and hit each other over the head with whisky bottles. Someone jumped out the window into the garbage cans in the alley. Oldenburg and Whitman were smashing holes in the wall and I said, “Don’t do it, the rats will come out.” So they picked up my brushes and paint and in the morning they had written rats, rats, all over the place.

BC: What made you play Olympia in Morris’s Site, by the way?

CS: It was a mistake. We were collaborating on something very physical where we were trying to develop my ideas and his resistance. We were pushing each other around and introducing malleable materials as we would move. We had been practising things in the basement of the Judson Church and Bob came up to me one day and said I have a completely different idea, I really want you to try it. I’ve built a little something in my studio on Grand Street. So we went down there and he had built this tiny little wedge into the wall that I was to balance on. And then he had three six- by-eight feet pieces of wood that he was going to put in front of me. I would be disappeared and as he moved the three of them, I would suddenly appear there.

BC: As Olympia?

CS: I guess Olympia was there from the beginning, I’m not sure. I was not happy about the little cat collar that was going to go around my neck. But it seemed to me that this was a chance to inhabit a stark image in a new figuration. And I would risk it the way I had risked being in Brakhage’s films, which were a disaster and a nightmare for me, in which I saw only deformation, distortion, projection, imposition and cutting away what my real occupancy of the space was about. Here we were again, and of course I was historicized and immobilized. But I was famous for that in those days. No one cared about Fuses or Meat Joy or anything else I was making. They said Site was exciting.

BC: A beautiful woman taking off her clothes was enough for them?

CS: It was more than enough. You didn’t have to do any of your own stuff. That was the message. Eye Body was despised as a set of images when I took it around, because they said if you want to paint, paint, if you want to take your clothes off and run around naked, then don’t bother the art world with it. If a man takes your clothes off, then it’s seen as having value. But if you do it yourself within a context that hasn’t already been clarified by male art historical definitions, then you’re confusing the issue and you’d better stop.

BC: Did you get pissed off?

CS: I was enraged. But I’m a double Libra so we don’t work out of rage. It’s just one of the ingredients. You don’t stay with it; you give it its proportion. Otherwise it’s too didactic or too eroding, and there’s not enough pleasure in it. But it’s a terribly valuable key to where you have to fight. I wouldn’t give up my rage for anything.

BC: In fact, much of your work has been a very intelligent way of fighting the resistances that you’ve encountered?

CS: You have to creep up. I mean, if I attack something in my culture I have to sneak up on it. I can’t hit it over the head with a hammer which is why all that smashing is going on with the full weight of the body in my early works.

BC:That’s a gesture too isn’t it?

CS: Yeah, it’s wonderful.

BC: It’s mark-making. You are a painter.

CS: It’s also about fixing and healing and changing. If you’re a painter and something’s wrong, we all say to ourselves, “There must be a way to paint it right.” •

Ice Box, 1963, construction in wooden box, paint, mirrors, glass, motorized fan, twigs, 27 x 40 x 18”.