Gillian Wearing: The Art of Everyday Illumination

Gillian Wearing, Me As Arbus, 2008, bromide print, 60.625 x 51.25” framed. All images courtesy the artist; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; Maureen Paley, London; Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Gillian Wearing’s most recent one-person show at the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in May and June was called “People,” not a surprising choice for an artist who has located human stories at the centre of her practice throughout her career. Her first New York show in eight years, “People” was conceived as something of a mini-survey that included both new and old work in various media: video, photography, installation and now sculpture.

The oldest work in the exhibition was Snapshot, 2005, seven videos for framed plasma screens that dealt with the evolution of still photography and also voiced an elderly woman’s bitter and poignant narrative of disappointment. In a version of Wearing’s confessional mode, the woman describes an inventory of frustration and anger at the way her life has turned out, while the framed photographs present us with a female version of the Seven Ages of Man. It is a telling focus: there has always been something both common and tragic in Wearing’s work and Snapshots continues that doubled duty.

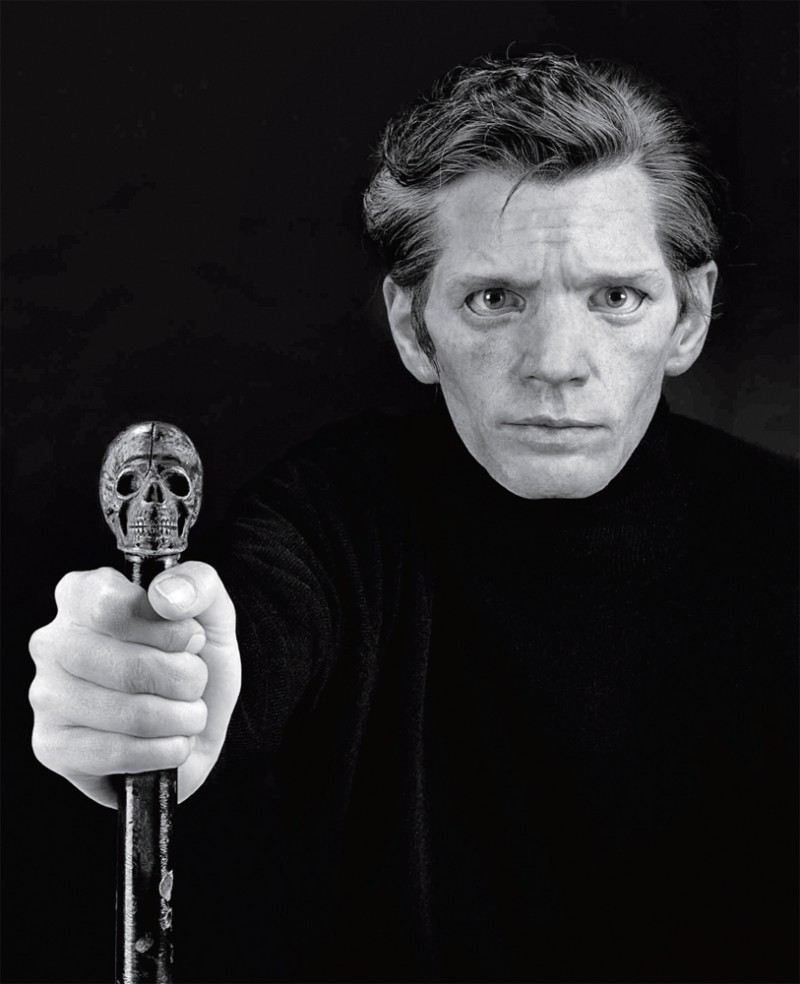

Me as Mapplethorpe, 2009, bromide print, based upon the Robert Mapplethorpe work: Self Portrait, 1988. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. 62.25 x 51.25” framed.

The exhibition also included three self-portraits in which Wearing paid tribute to an unholy trinity of artists for whom she has considerable admiration: Me As Arbus, 2008, Me As Mapplethorpe, 2009, and Me As Warhol in Drag with Scar, 2010. They are extraordinary, both in the accuracy of their portrayal and in the way they engage the layered history of portraiture in photography. This trio makes obvious connections to earlier of her works, like Confess All On Video, 1994, Trauma, 2000, and Album, 2003, in which masks were a2011device that offered to her storytellers a necessary combination of disguise and freedom. Wearing has always been interested in creating what she calls platforms that allow her subjects to articulate the “plethora of stories and experiences” they are waiting to tell.

In this sense, her work functions therapeutically in a healing arc that moves from the private to the public, from the individual to society. Wearing’s subjects (she likes to think of them as collaborators) tell stories that can be disturbing: there are narratives of all manner of sexual abuse, planned murders and suicides, ghoulish activities and criminal acts. But despite the bathroom cubicle and tabloid tone of Confess All On Video. Don’t Worry, You Will Be in Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian, her 1994 call for participants, there is nothing salacious or tawdry about her videos. Whether her subject is an uptight executive stuck in a 20-year-old voyeuristic memory of sibling transgression, an enraged and politicized gay man exacting a particularly unsavoury revenge on his boss in a pizza joint, or a cluster of inebriated street people demonstrating in equal measure their care and foolishness, she has an unerring ability to wrap a compelling story in a compassionate blanket. The achievement of her art is that everyone involved—subject, viewer and artist—emerges from the experience better informed and more empathetic than they were before their engagement. Wearing’s art is inclusively democratic. “I really do believe in the universal person,” she says in the following interview, and evidence of that uncompromising humanism is everywhere in her work.

The piece that provided the name for her New York exhibition was a bromide print called People, 2011. It is her most recent photograph and the first of what she intends to be a series. Based on Bouquet, a Jan Brueghel the Elder oil on copper painting from 1606, People is a careful re-construction of the Flemish master’s still life by way of silk flowers and leached colour. There is a hint of the commemorative in the genre; floral arrangements play a central role in our recognition of significant events, whether funerary or celebratory. (In this sense, People connects to her trio of tributary self-portraits.) But Wearing wants to use the still life as a hinge—it is still and alive—and Brueghel is her perfect collaborator. His appreciation of the individual character of each flower, and his ability to fit that unique nature into an overall composition, is what Wearing does specifically in People and in her work as a whole. Whether she is asking passersby on the street to write something they want to say on a piece of paper, organizing 26 individuals dressed as London policemen for a still-life video, or choosing the cast for a feature-length film, Wearing is involved in a process of gathering people together and in composing them, giving them composure. Out of that social construction she finds both the form and the content of her dignified art.

Installation view of Gillian Wearing’s exhibition “People,” 2011, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

The following interview was conducted by phone to the artist’s London studio on July 19, 2011.

Border Crossings: Was Dancing in Peckham a piece that was true to your authentic self?

Gillian Wearing: It was close to my authentic self. I had seen a woman dance in the Royal Festival Hall, and when I see something that inspires me, I don’t know what to do. I got frustrated because I was too shy to ask her, but then I thought, “What would I ask her?” It might be a bit of a shock to be approached by somebody who doesn’t really know why they want to talk to you. I think it was through that frustration that I started thinking about how could I take what I found inspiring and turn it into something else. And I do love dancing.

Did you just have the songs in your head so that this was a conceptual exercise as well as one in kinetics?

Yes. I’m not using headphones or anything. I created a tape at home on which I put snippets of all the songs I really loved. I thought if I could remember the sequence I wouldn’t dry up. The work became about things other than having watched that woman; it became about not feeling inhibited in a space where you are meant to behave in a certain manner. It was a practical shopping centre, not the centre of London where you get buskers or other street entertainers. This was a place where, if you did something odd, people would find it surprising. One old man who passed me said, “What’s the world coming to?” Other people, once they passed the camera, did a bit of dancing themselves. But on the whole, people would either walk past and accept that I was dancing, or ignore me.

Masturbation and “Take Your Top Off” have a certain edge to them. Were you conscious in that early work that you were putting pressure on the audience?

I’m not sure I was thinking about how society would view me. In “Take Your Top Off,” I was interested in people who were changing gender, who were being reborn in a way. Since I was photographing them, I thought how would I be imaged in the same picture? I was much more shy than they were because for them it was a new identity. Which comes back to the mask: it’s liberating when you can be someone else, and of course, they were going to be someone else for the rest of their lives. So they were quite proud, and they felt more confident than me in those photographs. This was after doing the “Sign” series, when I was questioning my own work rather than asking questions of how I fit into society.

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (I’M DESPERATE),1992-93, C-type colour print; (HELP),1992-93, C-type colour print, 48 x 36.25.”

Both of those bodies of work literally deal with the body, either your own or someone else’s.

With Masturbation, I had the idea of the mirror image going off into the distance before I had the idea of masturbation, so I was thinking of someone being self-involved. It wasn’t necessarily about body. The metaphor was really much more about psychology.

Many of the works prior to 1994 dealt with music. Has it played a fairly critical role in your life?

Yes, but I’d say inhibition has played a critical role. It was because I really didn’t speak at all; I couldn’t make a sentence. I left school at 16 and was an office junior at an insurance broker and didn’t realize at that point how anyone perceived me. There were two women at work who always hoped I would go to the counter because they wanted to see if I could actually speak. I would get out two or three words and then I’d give up. Then I would go on to the next sentence. That followed me for quite a few years, even when I was at Goldsmith’s, where a lot of people drew attention to the fact that I was inarticulate. I gave up reading books when I was 11 until I was about 29, and I wasn’t picking up verbal skills anywhere else, so I had to work quite hard to speak. Maybe that makes my work about the voice as well. I think it comes from the fact that I didn’t have a practical voice myself. It’s almost like a part of my brain doesn’t function correctly because I wasn’t taught to properly speak as a child. My brother and sister are certainly more articulate than me.

You don’t seem inarticulate now, so some distance has been covered

Well, some distance has been covered, but if you knew me back in the ’80s and the ’90s you’d have a different view. I remember I did one particular work at college where I cut up books. We had a seminar and someone asked me why I did that, and the only words I could say were, “I didn’t like books.” I couldn’t say anything else and that was the end of the seminar.

It would be easy to draw a connection between your own muteness and your unusual sympathy for people articulating their concerns. In some way, they are surrogates.

I wouldn’t say they are surrogates, though I am saying we learn a lot from listening to people. What interested me from the early days of doing the “Sign” series is that a lot of voices are not heard, and if we bother to stop and talk to people, they can break down our perceptions of them. But words and language have always been important to me, and I think that stems from my own sense of not being well educated and not being particularly verbal for so many years.

In some of your series you have gravitated towards work that is totally unlike you. In the “Pin-Up” series you move into glamour and extroversion. It’s as if some process of vicarious inhabitation is going on. Do you live through the experience of these people in having them articulate their anxieties or needs or desires?

I think everyone has needs, desires and dreams. We none of us are different in that. On the whole people are incredibly unique, but all their fears and dreams are shared. From the very beginning, particularly in “Signs,” I was looking outside of my own experiences. If the subject matter interests me, then I’ll try and make a piece of work around that.

1-4. Film stills from Sacha and Mum, 1996, black-and-white video projection with sound, 4 minutes, 30 seconds.

A lot of critics have talked about the ordinariness of the people in your work. But they bring revelations about murder threats, planned suicides and all manner of physical and psychic damage. So the conclusion I draw is that no one’s life is ordinary, or that the ordinary is inherently dramatic.

I don’t know where the term “ordinary” comes from because everyone is extraordinary, and if you engage with anyone they have a whole plethora of stories and experiences.

In Trauma, you run through a series of stories that are pretty bleak, a boy who planned to kill his father and a sexually abusive grandfather, and then you get to the woman who talks about her incestuous relationship with her brother in a way that makes it sound acceptable, almost a normal extension of her fraternal love. She’s apologetic in a very intelligent way. Then the final story comes from the abused kid who talks about the need for forgiveness. Is there a larger story about reconciliation that overrides the discrete stories in that particular piece?

In the confessionals, everyone brings a different take on what is in some ways a similar subject. They all have to deal with their trauma in a very unique way. I never set out to make a narrative arc with the traumas because they are on a loop in the gallery,and the viewer may come in on any of the stories. What I find with the “Confessions” is that they are told without someone else being the judge, or without having a voiceover telling you what to think. Obviously with Confess All, or even with Secrets and Lies, there are so many ways that people deal with what they’ve gone through in their lives. Who is to say what is the right way to do that? What is so incredible about those people is how articulate everyone is. Surprisingly, everyone was able to create something that had a beginning, middle and end. If I were to hear an anecdote, or if I were to tell the story of my life, I’m not sure that I would be able to do that. Maybe I’ve just been lucky in that the people who have come forward are able to give monologues. Nothing is tweaked and nothing is rehearsed.

It’s clear, though, that they have been thinking about it for a long time. You sense this has been rehearsed in their minds well before you showed up?

Absolutely. They are turning out a monologue that you would have heard in their heads. Maybe it’s something they have been able to put away for a moment, but then it comes back and they have to work it through.

What was your interest in the air guitar performers who appear in Slight Reprise?

I was interested in the passion of music fans and finding people who would bring that passion to what they do. You have an image of air guitar as being a cliché, but people bring so much thought to how they’re doing it. It’s also about a lack of inhibition to go off to this other world, as if they were being transported, but they’re actually in their own room. It’s how music can lift you into that different realm.

Do you envy people who have fewer inhibitions than you?

I do. Some people are not held back by genetic or cultural restraints. They are able to be quite open and gregarious, and it seems to come naturally to them.

Installation, Drunk, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

In Trauma and Confess All, why do you think people are so open with you? You have said that one of the things you admired about Diane Arbus was her ability to create a relationship with her subjects. Over the years you seem to have developed that same skill.

When I did the “Signs,” I was incredibly shy and stopping people was hard. In London, particularly during the ’90s, there were lots of people with clipboards doing personality questions, so it could be quite annoying to be stopped on a busy street. People just wanted to walk on, to go by as quickly as possible. But after they got out the first few sentences, they actually liked the idea. It wasn’t because of me; I think the idea was very appealing. It’s a question of finding platforms for people who want to speak. I don’t actually perceive myself as having any particular talent, though I am properly more versed in how to do it now than when I first started. I’m certainly not one of those people who other people come up to and start telling things about themselves.

I suppose in certain ways your practice of allowing people to wear masks opens up further possibilities. Even though they may be speaking their authentic selves, those selves are not visible to the audience.

Absolutely. I think people felt empowered by that. Because they wouldn’t be recognized, they could actually be more truthful. They could be themselves in their talk, but their outer body wasn’t being judged. When anyone talks, particularly in front of a camera, they are very aware of their self as a physical being. In “Confessions” you have a way of completely taking away all the evidence of who you are, but you can still say your story.

The mask is a very complicated device. The masks in Trauma are odd, and I know you wanted them to represent the person when the incident being recalled happened, even if it is 30 years earlier. Did you ever worry that they were so preposterous that they would get in the way of the story?

With Confess All I didn’t know if they would at all. I bought these joke-shop masks and moustaches and wigs. The advert had said that you could be in disguise, so everyone knew they would be wearing one. I thought masks would work because people often wear masks when they’re engaged in criminal acts. So it was just an off-chance idea. But even though most of them were joke-shop masks, they went beyond that, and a sense of power came through because of the integrity of how people spoke and the honesty of their stories. It broke down what that mask was meant to represent.

And in Trauma, the eyeholes give everything away. It’s the idea that the eyes are windows to the soul. When you see them, you know how much pain these people have gone through.

Yes, and because Trauma was a very sensitive area, I didn’t want joke-shop masks. So I had masks made, and they were like those in Greek theatre. They have a neutrality, and there is a kind of neutrality to young faces as well. So you have this almost neutral face and these pleading eyes telling the story. When you talk about eyes to the soul, that is exactly where you see the soul of that person.

You must have been moved hearing these stories. Were you often involved in an emotional way in what was going on?

Yes. In the work I do I empathize with people.

There are different ways for artists to act out their empathy. We found out later on that Arbus’s relationship with her subjects, with the dwarf for example, was that she wasn’t just photographing them but sleeping with them as well.

Her life was incredibly different from mine, and I keep a respectable relationship with people and would never be involved like Arbus. You can see from some of the work that she crossed that line. With my work I try and explain as much as I can to people, so they know exactly what we’re working on. Normally they just come on the day of the filming, and particularly if they have a confession, they’re filmed for a very brief moment.

The phrase “crossing the line” is an interesting one. Do you have ethical boundaries that you have set for yourself?

I think when you are doing anything with documentary you instinctively know what you shouldn’t do.

How influential were those television documentaries in the ’70s, like Michael Apted’s 7 Up and 2011 even the Mass Observation project from the late ’30s. Were you aware of the tradition of social documentary projects that had come out of Britain?

It’s interesting how you are shaped by the media you live in. We had lots of great documentaries in the ’70s and Michael Apted’s was incredibly seminal. It was one of those programs that everyone watched, and you’d have discussions at school with your friends. It was the sort of thing that got everyone talking. So being the only media and culture I knew, I didn’t realize that a strong documentary culture was particular to Britain.

Installation view of Bully, 2010, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, video for projection, 7 minutes, 55 seconds. Preview copy.

So did you think of yourself as a documentarian? Was that a tradition you considered yourself a part of?

In art school I was painting and drawing and doing installation, and it was only when I left that I picked up a camcorder. I had thought about going to the National Film School, but I had already done five years of education and I couldn’t bear to do anymore. So I borrowed a friend’s camcorder, and whilst I didn’t know what I wanted to do in the beginning, I knew I didn’t want to do television and I didn’t want to copy anyone. The one thing you learn at art school is that you should always have a unique voice. But I never really feel I’m a documentarian. There are elements of documentary in my work but it is not straightforward. I think if I’d gone to film school I would have been taught how to make things in a very traditional way. But a lot of those things have gone out the window because the way people make documentaries now is very different than the way they were made 20 years ago. Every one has had to adapt to the way technology and the world has changed. The audience has grown more sophisticated, and when the audience changes, you can’t continue doing things the same way. I think 7 Up has probably suffered in the long run. When they showed the last one, which I think was 49 Up, it got quite a small audience. Even though the subject remains interesting, people no longer relate to that old-fashioned format.

There is a distinguished documentary tradition in Canada as well through the National Film Board. The man who was instrumental in its formation was John Grierson, a Scot who emigrated to Canada to make documentaries to help the war effort. His definition of documentary was, “the creative treatment of history.” If you cast your emphasis within that definition on “creative” rather than on “history,” it gives you a lot of leeway to make art out of documentary. You have raised this distinction in your Homage to the woman with the bandaged face who I saw yesterday down Walworth road, when you say her mask was “more aesthetic than practical.”

I think with my own work, the film/photographic structures wear their metaphors on their sleeves. It shows why it is different from documentary; it shows you that I am replacing the woman with the bandaged face, I’m just filling shoes and trying to experience what it would be like to be that person. So the structure was very evident. There were a lot of problems in the ’90s in this country where real people were paid to re-enact something, but the audience at home wasn’t told they were re-enactments. I don’t think Grierson would have accepted that concept of creative play because it was actually pulling the wool over the audience’s eyes. If you creatively play with documentary, I think it is very important to show the structure.

Which you do in Family History, where the audience is made aware that what’s going on is both a re-enactment and a re-visitation through the interview with Heather many years later. You consciously bring a structure of awareness to the audience.

Yes. The audience knows what it is and the people who are being interviewed also know. So everyone is involved with the creation of this new structure.

Family History is interesting because the television journalist’s interview with Heather is innocuous, mostly informational, until the moment when she recalls her encounter with the psychologist and the career counsellor, who basically treat her as if she is lower class and won’t amount to anything. Decades later you can still sense Heather’s tension and anger.

Yes. Heather is just slightly older than me, and we would have come from a generation and a background where no one would give you any chance, and no one would expect anything of you. No one ever expected anything of me.

They expected you would either fail or be mediocre at best?

I can talk for myself coming from Birmingham, where you were either going to be a junior office clerk or you would work in a factory. Those were your only two options, and they wouldn’t have entertained anything else. I remember my career advisor looking so bored that she couldn’t wait for me to leave the room. But it was also an era where the majority of people would have been either working class or lower middle class and aspirations were few and far between. You couldn’t have too many aspirations because there were no opportunities. Now there is a plethora of choice, but then, there was really very little choice. A whole generation of us had the same career advice. It wasn’t career advice—it was just telling you that’s your lot, so get on with it.

Did you come from a working-class family?

Yes. I went to a comprehensive school and left at 16 with no qualifications. There were no books on art. I gave up art in my third year of senior school at the age of 13. I did pottery in my final year, but I failed that as well because my methodology was very weak. I had air bubbles in my pots, and I blew up my classmate’s pots. They had to re-do theirs, but I was just disqualified.

You have said that all your work is about portraiture, and I wonder what is the nature of the portrait? Does it add up to a view of what Britain is, or what your generation is, or the class you came from?

I would hope it is as universal as possible. Sometimes people perceive, like in “Confessions,” that the subjects are working class, when there are also upper-middle-class and upper-class people. Actually, the majority is middle class. I don’t know where that perception came from, but I think it has to do with the history of documentary in Britain, which has primarily been watching working-class families and working-class life. I tried to include everyone. Until the day of filming, I don’t know what anyone’s background is. You can normally tell by someone’s voice, or they sometimes tell you their occupation. One of the people in “Confessions” was a senior executive in a large company. I haven’t gone out of my way to make class-conscious work. I really do believe in the universal person and that, regardless of our background, we share a number of things.

In “Snapshot,” the older woman who is narrating the story is essentially mean-spirited; at the same time, hers is such a poignant story. She admits to so much. It is an amazing tract of inadequacies.

Yes, it’s very difficult being old. The sense of it is that you go through a whole life and, at the end, all the things you might have gained are gone because no one is there to actually support you. The loneliness and the anger is what comes across most powerfully. After all those years, no one wants to talk to you, so you go and talk to the shop assistant in the supermarket.

You say the camera lies. Is there a way you can exploit the discrepancy between the camera’s truth and the truth of the articulated voices?

When I said that I probably wasn’t thinking of a lot of my work because, obviously, when people speak and they are not edited, then that is a truth and there is nothing you can say against that. So the camera is not lying when it is locked off and someone is talking. I think when you are doing a highly edited piece of work you can go back to Grierson and the idea of being creative with the truth. That’s when there is a sense that another truth may be evolving. When I was doing Broad Street I had reels and reels of footage and made only a short film. So there was a lot of stuff that was not in the final cut; only the elements that I felt worked together got included. It’s in that sense that I was discussing lying as being editing. It’s not really a lie, it is an edited truth.

1-3. Trauma, 2000, film stills, back projection, 30 minutes.

There are photographers like August Sander and Richard Avedon when he went to the American West for Rolling Stone. They were systematically documenting a culture. Have you ever felt the need to be more systematic?

No, I don’t think along those lines. That kind of photography has become a genre in itself, maybe created by Sander. At the same time, you can see that his portraits are highly standardized. Everyone seems to stand in a very austere way, and if you go back to photographs from the same era, people would never pose that way. So there is a look that is very personal to him, and he has since influenced so many generations of photographers. It becomes a technique, but it is only one technique for documenting the world. There are others.

In your portrait of Lily Cole you take her extraordinary face, then you have a mask made, and then you bruise the mask. I couldn’t help but think of Rimbaud’s poem, “One evening I sat beauty on my knees/ and I found her bitter/ and I abused her.” What was behind your notion of taking that face, obscuring it and then messing with it?

A mask can be quite scary and eerie, but in this case you have sympathy towards it. At the end of the day it is just a mask, but I was playing on this sense of the Victorian doll and how touching something is when it is physically damaged. Also, Lily Cole has the features of a Victorian doll. But it wasn’t that I was damaging beauty as much as re-appraising the mask and asking if you can have some kind of empathy for it if it slightly damaged; does it feel somehow real because it is broken?

I can’t resist asking about you and masks. When you do your _Self-Portrait _in 2000, you put on a mask of you.

I thought it would be good to wear a mask of my own face as it was then, and on a whim, I thought I’ll take a photograph of me wearing it. It ended up being a very striking image. What I didn’t realize, and this happens a lot in my work, is the double take. People have to look again. You think you know what you’re looking at but you don’t. I think the Self-Portrait with the mask works quite well because I managed to make my hair look quite wig-like, and from a distance, because the colouring of the mask is very similar to my neck, you think it a face with a blank expression. It’s quite enigmatic as an image.

Where did the idea come from for “Album,” where you cast yourself as members of your own family? Was that unusual territory?

Well, it was new territory. I was going through some old photographs and found one of my mother. I had fixed the photograph in my head. It’s an old-fashioned haircut, and not many people have a set hairstyle. When I was a child and looked at this photograph, it really was of an older woman. When you’re flicking through photographs you don’t really look at them. So over the years, in a Dorian Gray kind of way, I started aging it. If I was thirty, she should have been maybe 60. Then when I found the photograph again, all of a sudden I saw a young woman of 23. I got quite scared and realized that I was an older person and that this young person was my mother before she met my father. She was younger than me, and so I felt slightly more protective towards her. Then I decided, because I looked most like my mother, that it would be interesting to try and be that optimistic young person. That’s when I had a mask made.

Then did you realize you could do your immediate family in the same way?

Yes, I thought I’ll create my whole family. But it was one of those things when you start out you ask yourself, how should I do the mask? should it look very realistic? should I just put on a wig and wear makeup? I wanted it to be as close to the original as possible. Again, going back to the eyes being the important thing, there would be these false features and my real eyes.

Confess All On Video. Don’t Worry, You Will be in Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian…, 1994, colour video with sound, 30 minutes.

Let’s talk about your three-part self-casting as Warhol, Mapplethorpe and Arbus. They are extraordinary images. Why was verisimilitude so important?

First of all, the work of all three artists has a lot to do with masks. When I was thinking of Warhol, the images that stuck in my head after all these years is the one Avedon took where Warhol is showing his scar (it’s quite shocking, but he also looks quite cool), and the other one was the Christopher Makos image where Warhol is in drag. He does similar poses in a way, and both have this sense of him being very much in charge of his image. It was all about reference, because Makos is referencing Duchamp doing Rrose Sélavey. I was referencing Makos; Warhol was referencing Duchamp; and then there is Avedon as well. So all these different photographers are trying to capture this enigmatic person. To a certain extent, Warhol was someone who was always in disguise and who always enjoyed playing with it as well.

In the Mapplethorpe, you inhabit the portrait he did when he is dying of AIDS and is holding this death head cane. That must have been a very conscious choice about when to pick up his life. You could have pictured the Patti Smith vibrant, sensual days when he looked like a beautiful biker.

But that final portrait is just amazing, one of the most powerful self-portraits I’ve ever seen. It’s up there with Rembrandt. It’s that moment when he is facing death, so it’s like his death mask. I don’t know how any viewer cannot have some engagement with that image. We all think about mortality, but how do we deal with it? As an artist he dealt with it so frankly by creating a beautiful and powerful image. I couldn’t shake it out of my head.

And when you do an edition for Parkett you essentially do a death mask?

Yes.

What is it about Arbus that has her riding on your shoulder?

I think because she built a powerful body of work with amazing images that were identifiably hers. I wouldn’t want to step into her shoes and do her work, but I really admire it. I actually didn’t know much about the work until I did “Signs” and someone pointed out that our work was similar simply because I went up to people in the street. But some of her photographs are just sublime, and there is a very strong aesthetic that goes with her work. They are not really of this world. In the same way that Sander made a picture that looks like a Sander, she was able to do that through editing. We realize now from her contact sheets that a lot of the photographs look like anyone, but then she finds that one right image. Another thing that we have in common is the eyes. Whether they’re thinking of something or whether they’re daydreaming, they look hypnotic. They’re all haunted in some way. That’s how you enter her work. My work is always about interior. I do also work with the exterior, but that is where you enter into the interior. You can trace that back to the “Signs”; what the people are saying is interior, even though the words are on the outside. It is really what they are thinking inside at the moment when I photograph them.

Self-Portrait, 2000, C-type print, 67.75 x 67.75.”

Did you ever worry that you were a kind of clinical ethnographer? So with Drunk, for example, you place these people in a situation and you observe them and film that process of observation. Were there ever questions about should I be doing this, or should I be doing it differently?

When I was working with street alcoholics, I made sure that I got to know the people very well, so that took a two-year period. Most times when we would meet, everyone was already inebriated. Of course, there are moments when a sense of sobriety would come over them because the body can’t be in a perpetually inebriated state twenty-four hours a day. To me what the work was strongly about was going back to this sense of being inhibited or not inhibited. We drink to be outside of ourselves, to lose our sense of rationality. Even if it’s young people going to clubs, we sometimes want to escape the sense that we are constrained by the society around us. Obviously, I couldn’t do that with people who wanted to be anonymous. Street drinkers are very honest about what they are. It was really important to me to film the effects of drink, and so that’s why I got to know the people. They would come to my studio and I would film them, and all along the line they knew exactly what it was we were doing. I found it to be a very beautiful piece. It goes through all the emotions—it’s not just about losing control. It’s sad that people drink, but there’s a lot of love and affection in there. I was creating this portrait almost as if it were a drawing or a painting; that’s why it’s in black and white. When you take away all the effects of a home and put people in a studio, then it becomes all about the person. It is about people losing their inhibitions. It’s really about the human condition. I thought about the piece long and hard, and that was why I spent so much time doing it. I felt that Drunk was an important piece to do and I feel really close to it.

Self-Portrait at 17 Years Old, 2003, C-type print, 45.5 x 36.25.”

I want to talk about emotion in the work. In 2 into 1, re-inhabiting the voices creates a real tension. When the mother says how close is the line between love and hate, it draws attention to the fact that a lot of your work recognizes the complications of emotion. Certainly I Love You does that by returning to the phrase that is articulated in so many ways—from a scream of hatred to the declaration of a need to be cared for. Is one of the things you want to exploit that range of emotion about the line between love and hate?

I suppose I want to show how complex relationships are. There is no one state that anyone ever is in in a relationship. I remember reading years ago that the elastic band breaks the closer you get to someone. But all relationships are complex, and so I wanted to find people who could be very honest about that. When I went to interview Hilary and her two sons I didn’t prescribe what they should say. The interviews with all the family members were done in an hour and they were so open. Even though that is a very particular relationship, because she talks about her sons and they talk about her, I think a lot of people relate to it. You could take a sense of what they say and talk about a relationship between two adults, or whether they were partners or siblings, in fact any close relationship. I was trying to create that honesty and openness. When people are that close, some of the opinions have actually come from the other person and some of them are people striking out with their own identity. In Sacha and Mum, I was thinking about relationships and the closeness of love and hate. But it’s more ambiguous than in 2 into 1 because you can’t really tell what the relationship is in Sacha and Mum. Is the mother restraining the daughter because the daughter is wild, or is the mother the nasty perpetrator? But it was really a metaphor. I didn’t want it to be literal, and that’s why I liked having two women actresses playing the parts. It would be easier to understand the violence if it were male, but having it be two women is much more interesting and complex. What I wanted was that you couldn’t explain it completely; there’s obviously love involved and there is violence involved, and it is quite disturbing to watch. It is domestic and it looks very cozy at the same time. There is a moment where you think the mother is being very loving, and then all of a sudden she changes.

The thing that is so captivating for the viewer is this sense of the unexpected, which you addressed earlier, so watching those videos involves a disjunction between identity and voice that the viewer has to deal with.

To me it is more about voices coming from the person who is not saying it. First of all, you can see the apparatus straight away because you can tell that voice doesn’t belong to that person. So you can actually illuminate a truth—not the truth of what people are necessarily saying, but the truth about the way we live.

To illuminate the truth is a lovely phrase, because it carries with it a range of metaphors of its own. Do you sense that one of the things you’ve been able to do in your work is bring out a sense of illumination and, with it, a tremendous sense of empowerment for the people you talk to? Is there a larger ethical and social purpose in your work?

Definitely in that sense of empowerment. Again, I didn’t know this when I was first doing the work, so I didn’t know what it entirely meant when I was doing the “Confessions.” But I got a sense that when people came away, they felt something had been lifted off their shoulders, and that went through into Trauma and other works that I’ve done, even in Family History with Heather. What people want is to tell their stories. In Heather’s case, she wanted to re-tell her story from where she is now. But particularly with the confessional work, they want to tell their stories to a wider audience to get some degree of understanding. Also the fact that they have spoken the words actually makes them feel some kind of relief. People thanked me because they were relieved to tell their stories without the consequences of telling someone else. They can’t tell their loved ones because the story is too tragic.

Self-Portrait as my Mother Jean Gregory, 2003, black-and-white print, 59 x 51.625” framed.

A critic of your recent show in New York says your work is psychologically rattling. You must think of it as being closer to psychologically illuminating.

Let’s look at reality; let’s look at the truth of people telling their stories. As I said before, it’s one aspect of the truth. We learn a lot when we listen to people and also listen without someone telling you what to think. I try and treat both the participant and the audience as intelligently as possible.

That would explain why none of your work makes judgments about the people and their stories. Clearly you have no interest in playing moral arbiter in this world.

Not at all. But we can all be judged, and I think a lot of people have had plenty of judgment applied in their lives. I don’t want to put in more. What is particularly interesting is that I find the audience will give empathy when no judgment is being made. They may not always agree, but they are able to understand because of the way the story is told.

It frees everyone up. It’s a generous way of making art. Do you think of the people you work with as subjects or collaborators?

I’d like to see everyone as collaborators, but obviously, collaboration operates at many different levels. People are coming in and giving a lot of themselves; they shape their narratives and bring ideas to the plate, so I see them as collaborators as much as possible.

What generated the move to a feature-length film? It is consistent and logical, but it is also a pretty big step to make Self Made.

Self-Portrait as my Father Brian Wearing, 2003, black-and-white print, 64.625 x 51.375.” 49376txt.

I’ve been entertaining the idea of making a feature-length film for many years, actually, and I had been putting in applications back to the mid-’90s, clearly without much success. I really applaud people who are filmmakers all their lives and who stick it out, because a lot of it is struggling to get funding. The great thing about art, even though you can make it more complicated and expensive, is that it can be produced for very little. I made a lot of my early work for about £500. But the application processes you have to go through in film can really thwart your confidence at times because you’re constantly being rejected. But I stuck it out because I wanted to do a long-form film. It was a process of elimination, where 10 or 20 artists were asked to put in an idea, and it was a whittling down process. As the ideas got developed over the course of two years, they chose me to make the final film.

Is this the first time you have actually worked with a playwright?

In I Love You and Sacha and Mum, I worked with actors, but I’ve never worked with a playwright. Feature-film is a collaborative process anyway, and so I worked with a playwright, Leo Butler, and Sam Rumbelow, a method-acting coach. I also had a script editor, and so I was working with a lot of different minds. It’s great to have someone to talk with about ideas and it gets things done; your mind works quicker when you’re talking to someone else rather than yourself because, if it’s just you, there is no one filtering your ideas.

What criteria did you use to select the seven people who appear in the film? Was it their susceptibility to being able to work with Sam and his method?

First of all, I chose people that I liked and who had good stories. I had found 12 people from London auditions, then we did a trial workshop in 2008 when Sam came on board, and we decided on 4 people from that 12. He was also involved in the second tier of auditions that were held in Newcastle, where part of the funding came from and where the filming occurred. For this audition, Sam tried method exercises with each person, so it was very much how they could work with his method.

Film Stills from Secrets and Lies, 2009, video for monitor with sound, edition of 5, 2AP. 53 minutes, 16 seconds.

You have said that all life is partially fictive and also authentic, and how we decide upon the division between the invention in our lives and the actuality of our lives is difficult to determine.

There is a great quote that man doesn’t live in reality, he lives in dreams. What partially keeps us alive is that we live in our dreams and in our hopes. The sense of living in the now is the hardest thing in the world, and what method class teaches you is to be in that moment because you can be very creative when you’re there. But we all live in fictional states because we are all living in what we hope for and what we want to gain in life, whether in relationships or in work. We try and think of the future a lot and we’re living in the past, so it is very hard living in the present. All our lives are a mixture of past, present, future, hopes and dreams.

Back in 1998 you said in an interview that you weren’t into “nicely finished-up stories.” Are you now more interested in a sense of resolution in your narratives?

Did I say that? I can’t quite remember. There is something about resolution that is very satisfactory. We’re drawn to endings; we’re drawn to knowing what an outcome is. I don’t know if I’m going to do more of that, but I’m very conscious of it. There is a lot to be said about having something that gives you a summary at the end. I’m having a show at Whitechapel and K20 in Dusseldorf next year, and I’m working out an idea, which keeps metamorphosing. It could be totally written or something that is not written at all. It’s up in the air at the moment. The hardest thing when you have so many thoughts is to try and simplify something.

You’ve said in the past that you are interested in how other people put things together because they can say something more interesting. Do you trust that you also have some interesting things to say? Have you broken the silence barrier? I don’t know. We’ll find out. ❚

Film Stills from Secrets and Lies, 2009, video for monitor with sound, edition of 5, 2AP. 53 minutes, 16 seconds.