Sylvia Matas

In Sylvia Matas’s exhibition “Stop the Clock and Open Every Window” (YYZ Artists’ Outlet), the walls of the gallery space divide the work into four neat groups. This distinction appears at first to replicate divisions among media (drawing, photography, text, video, paper cut-out), but each wall elides such neat categorization. The divergence between inside and outside (both nouns and prepositions; a building, time, a universe) is understood as a shift among multiple modes of perception and figured in architectural forms and clock faces, among other remnants of the world.

In her 2019 book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, artist and writer Jenny Odell describes how attention can operate as a mode of resistance to a culture of capitalist productivity in which our very capacity to pay attention (to art, to nature, to each other) has become a commodity. Odell argues that it is not simply through retreat that we might rebuild a mental bandwidth for staying with ourselves but also a retraining through refusal. Allying an “I would prefer not to” to an ecological framework of care and attention can bring about a shift in perspective.

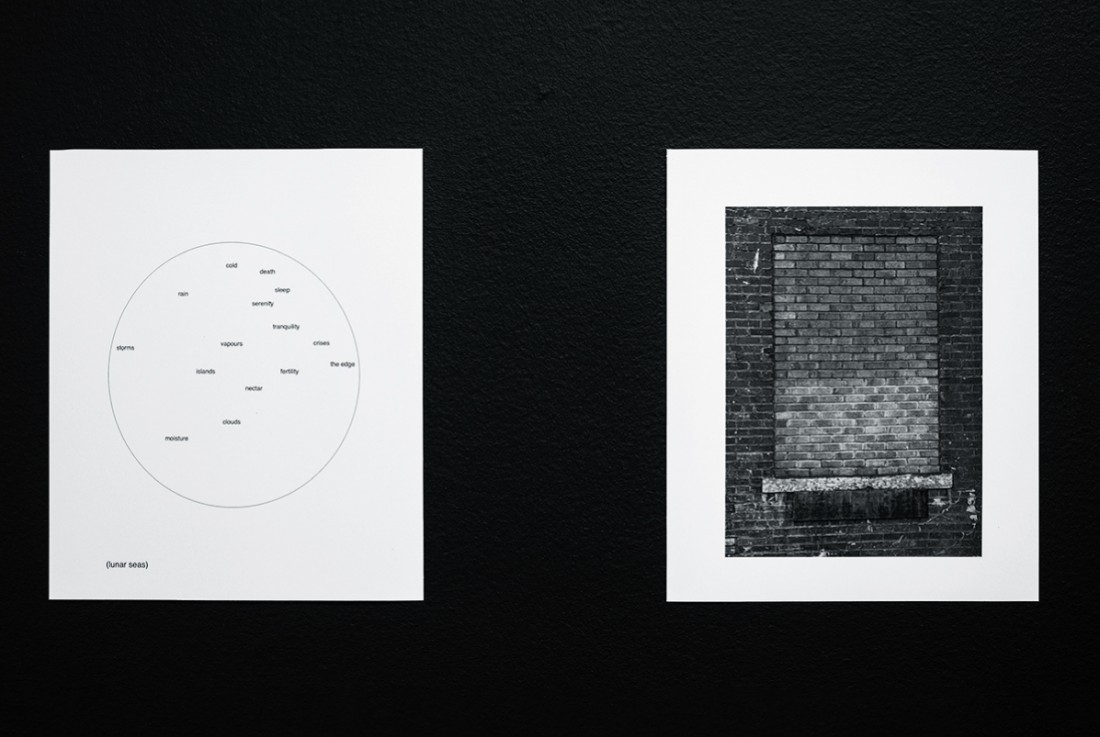

Sylvia Matas, A Reversal of Winds, 2018, bookwork (deconstructed), 8 x 9.5 inches, 20 pages. All photos: Yuula Benivolski. All images courtesy YYZ Artists’ Outlet, Toronto, ON.

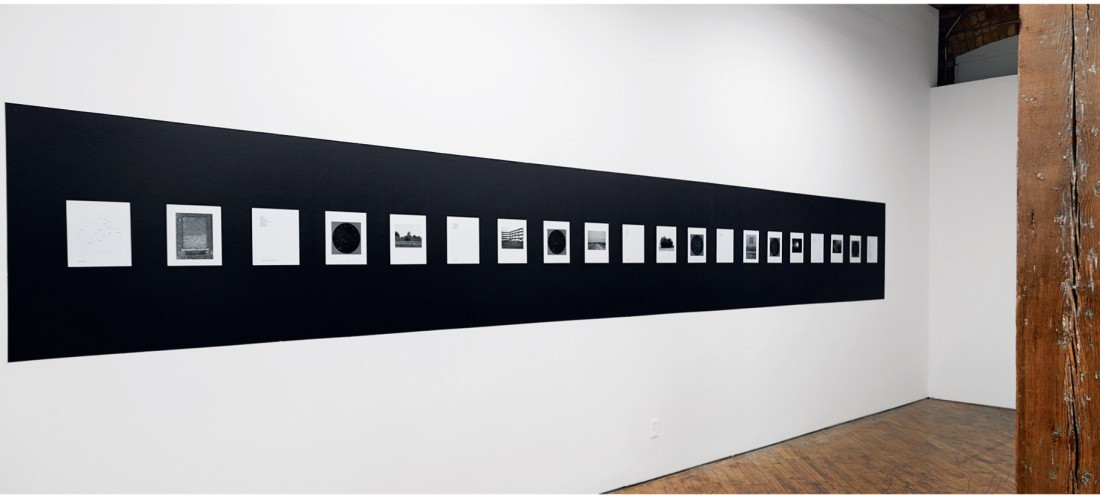

It is to this shift in scale that Matas has turned her attention. A wall of magazine pages are cut out to leave behind only words indicating the passing of time. Word diagrams (sometimes taking the form of poems) are interspersed with what appear to be images of constellations at different magnifications and photographs of architecture in slow return to a different state of being. Two evenly spaced wall-mounted monitors sit across the rectangular space of the gallery from the cut-outs, which in their solidity and material weight fill out the fluttering frame of the paper. A car cresting a small hill is frozen (at 50 kilometres per hour) while a tree branch wavers in a breeze. Framed artist books hold drawings that alternate between clock and built form.

For this interpretative mind, it is hard not to hold words to account for images, but to do so in this context would be a failure to acknowledge the absences so prominent in both Matas’s text and visual formulations. “bell-like/ soft-pure/sometimes short/hear for miles/hollow, haunting, flute-like/ high-pitched/chattering/dismal shrieks/silent in winter”: in Matas’s words these are the vocalizations of extinct bird species. Paired with a bricked-in window, both sound and brick trace between interior and exterior what was once an avenue for life and interaction. Architecture stands in for the passing of time but not simply, in the way building materials might experience time differently from birds (extinct or no).

The concurrence of detail and scale (the sound of birds and the shape of the galaxy) underlines a less abstract relation between time and space. In Matas’s narratives,insofar as they can be understood as narratives, time passing (an extinction) is correlated to an expansion of visual perspective on the universe. This connection is made explicit in a list labelled “notes on stones.” Matas writes “to see the future/to mark the path/to protect from the sea/to bring good luck/to see the stars/to remember.” Seeing is articulated as something beyond just an experience of the present, the visual positioned as a way to recall the past and divine the future. Of the list of “methods of divination,” included among these other inventories of words, the strategies for seeing beyond the present offer a distinct model for perceiving the world and one in which sustained attention is required to make sense of the portents along the way.

Installation view, “Stop the Clock and Open Every Window,” 2020, YYZ Artists’ Outlet, Toronto, ON.

Combining electronic clock face and architectural fragment, the framed drawings appear to enact such a process of divination. To return to the title of the exhibition, stopping the clock and opening every window offers the possibility of interrogating the relationship between the experience of time and perceptual possibility. Is stopping the clock a denial of the passing of time or is it simply a losing track of time? Is misplaced time akin to a decaying building, something constructed with purpose yet out of sync with the present?

These perceptual possibilities are also figured in the empty space of the cut-out, with material removed to leave the passing of time in relief, not unlike a decaying architectural structure. In calling our attention to such signals in the physical world, Matas parallels the many media she rallies to her cause with the different modes of attention required to perceive nuance in the world around us. But what of people? For all the relations proposed between the observer and the objects pictured, I wondered what cadence of communication was proposed for human relationships. There seems to be the possibility that the observer (and the community they carry within and around themselves) is lost somewhere among bird, building and cosmos. Are human observers simply marking time? Both window and clock (stopped and open) imagine a fixed subject position that may need to be unmoored from simple affiliation with past and future and newly situated in the present. ❚

“Stop the Clock and Open Every Window” was exhibited at YYZ Artists’ Outlet, Toronto, from January 18 to March 14, 2020.

Emily Doucet is a writer, lecturer and PhD candidate in art history at the University of Toronto.