Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Surfaces and Distances

Christina Arza, Maude Arsenault, Mikael Levin, Linda Troeller

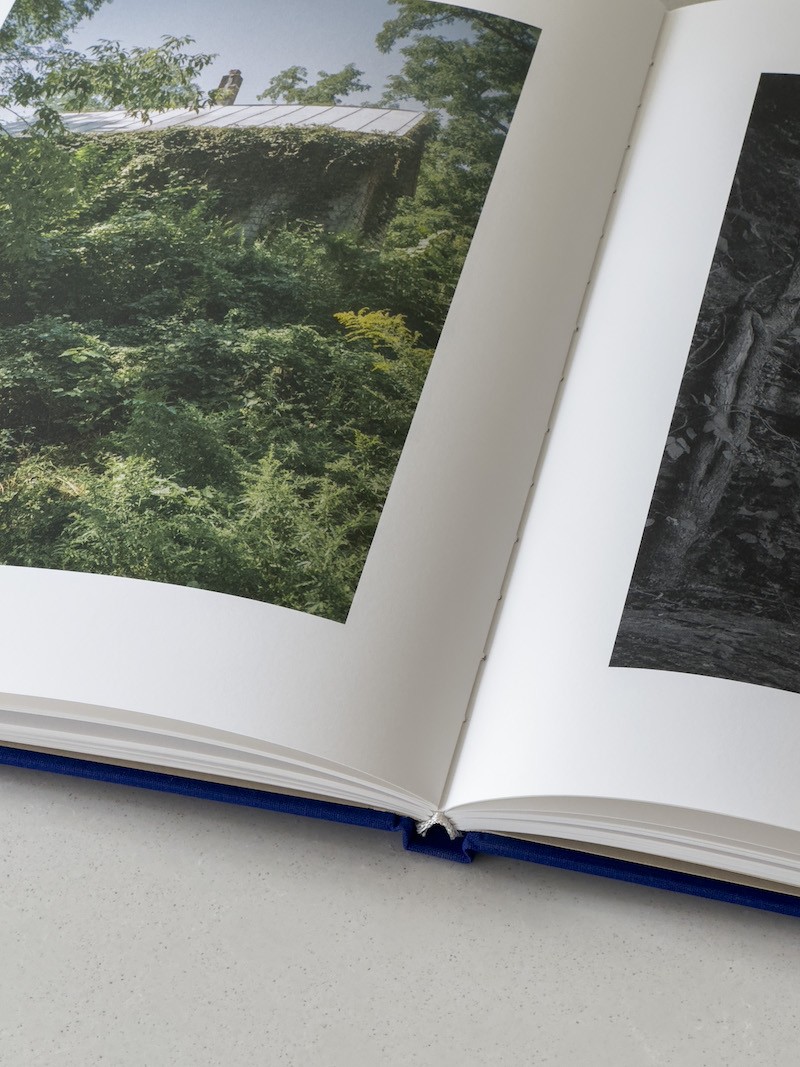

Imperfection has its poetry, which is also to say: It can be a form of perfection. In fact, we perceive everything so imperfectly, don’t we?—and then we create machines to make up for our imperfections. But the machines have their own imperfections, and all the more so do our uses of them. That’s true of the camera, maybe, more than of other machines. Or so I began to think as I wandered through slowly, tenderly, the first book by New York-based Cuban- American photographer Christina Arza (self-published, 2024, edition of 500). The hardcover book comprises 92 images followed by a letter from curator Arden Sherman and a conversation with Julie Dayer. I wandered through the book, I say, meaning the pages took me along no determinate path through a daily life, almost anonymous, that takes place mostly in Europe or upstate New York and a little bit in Florida, though place does not seem the concern; their sequence always seemed to make sense but did not impose itself, and I found myself proceeding just as the title promised, slowly and tenderly.

I speak of imperfection, in this case, because so often, in looking at Arza’s images, my attention is drawn to their grain, to a slight blur or to some compositional quirk that throws me off balance, as much as to the ostensible subject. A little girl stands on tiptoe, exposing the dirt on the bottoms of her socks, to contemplate the greenery outside a misty window, which she touches with one hand like Doubting Thomas, but it’s the film of condensation that fascinates me more than the girl or the room she inhabits—and in that, I’m just like her. Another picture looks down from above at someone, a woman, if the top of someone’s head gives a clue, gazing through binoculars at the surrounding darkness. No idea of what she might be looking for, but who cares when I can dwell on the light reflecting off the part in her dark hair?

But I want to go back to the beginning and linger for a long while on the first image, one of the few in black and white: in the background, an overcast sky over Parisian rooftops and buildings more clearly delineated than the figure that occupies the extreme foreground, a woman looking away and down at the urban scene as she extends her right arm, crossing the frame from lower left to upper right. The arm looks weirdly stretched out, elongated, as if seen through the eye of El Greco, and flattens out from volume to shadow as it goes. It’s as if the arm is trying to curve around to the viewer’s side of the picture.

The pictures are full of people but not their faces. When one shows up—the photographer’s, in a mirror—it almost comes as a shock. In one picture, she touches the mirror with one hand while, with the other, she holds the camera away from her face, as if more intent on seeing her own eyes in the mirror than in seeing what the photograph will show. The photographer’s gaze does not determine the image but is reflected in at some angle to that of the camera’s. That discrepancy makes for the beautiful imperfections that emerge, yes, slowly, tenderly, in Arza’s book.

Christina Arza, slowly, tenderly, edition of 500, self-published, 2024.

Christina Arza, slowly, tenderly, edition of 500, self-published, 2024.

Christina Arza, slowly, tenderly, edition of 500, self-published, 2024.

Christina Arza, slowly, tenderly, edition of 500, self-published, 2024.

Christina Arza, slowly, tenderly, edition of 500, self-published, 2024.

Christina Arza, slowly, tenderly, edition of 500, self-published, 2024.

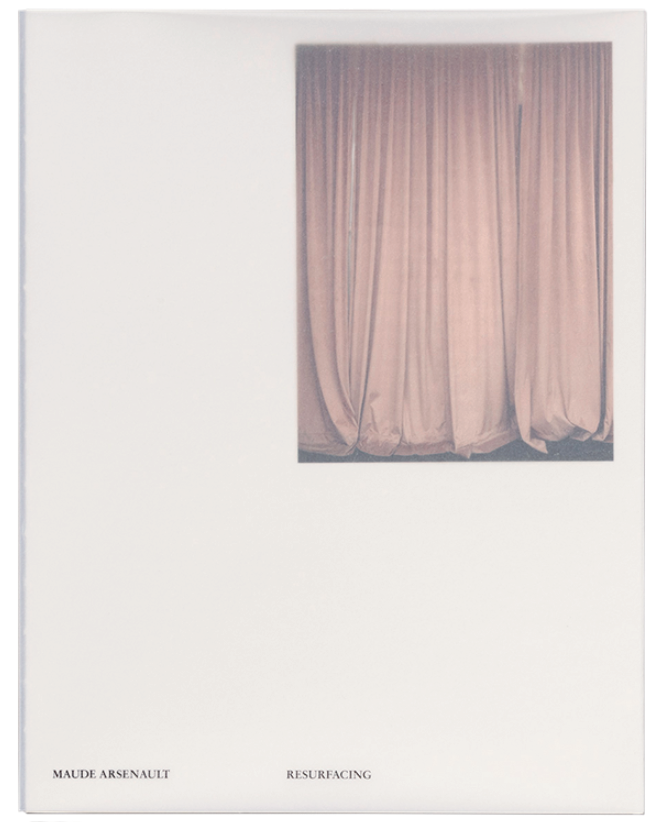

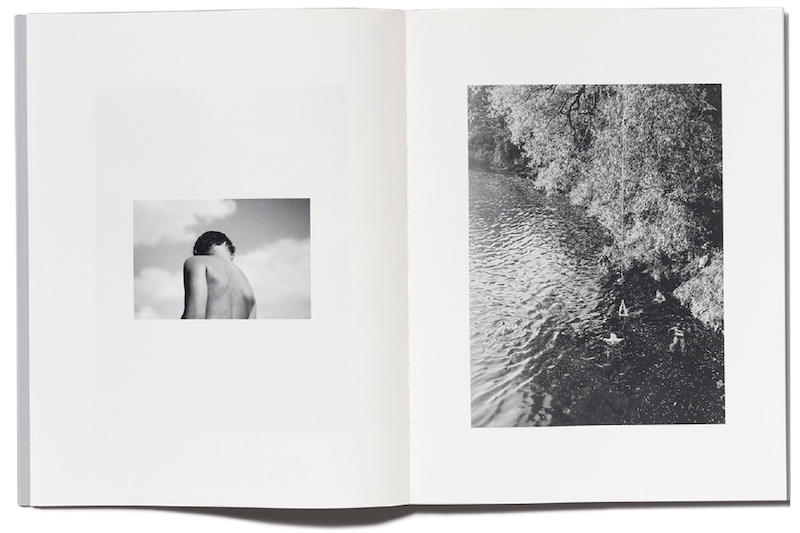

A similarly slow immersion into everyday life takes place in Resurfacing, the most recent book by Montreal-based artist Maude Arsenault (Deadbeat Club, Los Angeles, 2023). But in her photographs—more often monochrome than colour, and with the chroma often tamped down to such a degree that the difference between grey-scale and colour often becomes vague—she casts a cooler eye on things than Arza typically does. Again, the title tells the truth: the surfaces of things count for more here than depths. A distant view down from a height of four kids swimming in a river under overhanging trees becomes a single inflected plane of unbelievably variegated dapplings; the evident spatial recession is overcome, and compositional drama crystallizes around the pictorial seam that is a rope hanging from, presumably, a branch that would be jutting out just above the edge of the rectangle and pointed to by the arms of one of the young bathers—at first I thought he was holding the rope, but, no, it comes to its knotted end somewhere above his extending arms. It’s the photographer’s observational fortune that made the boy seem to play the part of an anchor, putting tension into that slender white line that is in fact dangling quite freely.

Texture is everything in these approximately 70 pictures, but what is texture other than the light that reveals it? In an interview with Tracy L Chandler, Arsenault speaks of her recent work as a reaction against her earlier profession of fashion photography: “I’m interested in the cracks, I’m interested in the scars, I’m interested in where beauty can reveal itself through the folds.” Things and people are seen at oblique angles—the gaze rakes across them, so to speak. A scrunched-up mass of tulle fabric with some light playing across it or the wrinkled skin around a shut eye are as much landscapes as a canopy of trees seen from above, and all are equally manifold surfaces. The minute level of detail in many of these images conveys a vivid sense of the world’s vastness. The word “resurfacing” can also mean something like “re-emerging,” and that’s the feeling that book leaves me with: of someone suddenly lifting their head above water and being astonished that things are as they are. The book’s only text other than its colophon information is a brief poem in French—a sort of prayer of gratitude for freedom.

Maude Arsenault, Resurfacing, published by Deadbeat Club Press, Los Angeles, 2023.

Maude Arsenault, Resurfacing, published by Deadbeat Club Press, Los Angeles, 2023.

Maude Arsenault, Resurfacing, published by Deadbeat Club Press, Los Angeles, 2023.

Maude Arsenault, Resurfacing, published by Deadbeat Club Press, Los Angeles, 2023.

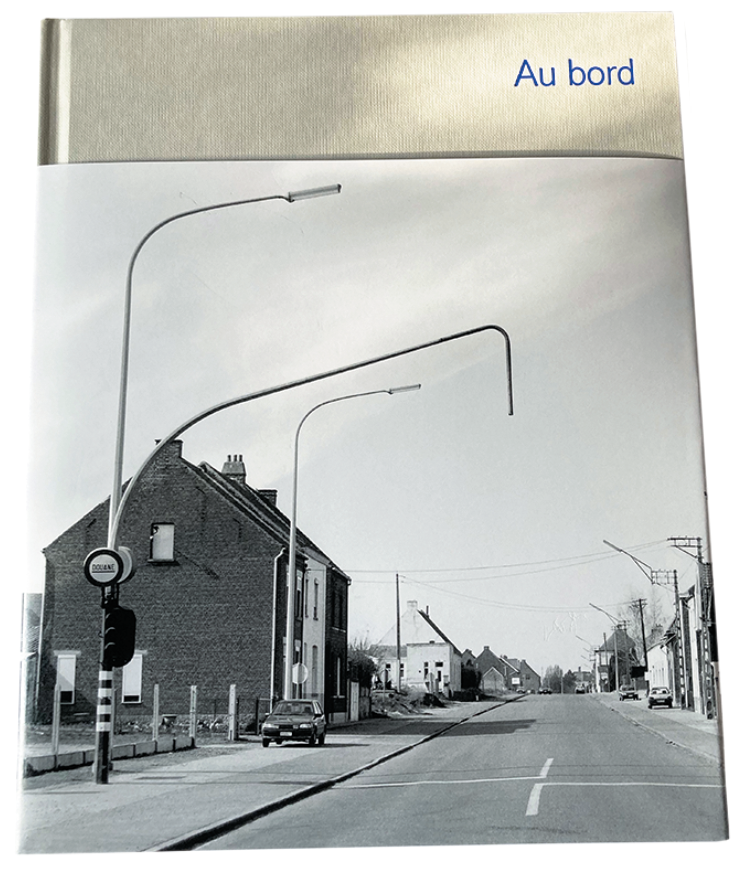

A more disillusioned and ironic view of freedom emerges from Mikael Levin’s Au Bord (Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022). In an introductory note, the Long Island-based artist explains that the 90 or so black and white images that make up this project were taken in 1993, just after the Schengen-mandated opening of France’s borders with its eastern neighbours. The book traces his travels from Bray-Dunes on the border with Belgium, which Wikipedia informs me is the northernmost point in all France, down to the Alsatian town of Chalampé, just across the border from Neuenburg am Rhein, Germany (and near Basel, Switzerland). His mission: to photograph all the recently abandoned control posts, on both sides of the line, along the way.

“There was a lot of optimism about … the free passage of people and goods between member states,” Levin writes, and besides, if it were the case, as some claim, that everything in the world has been photographed, these structures might be a sort of exception: No photography was allowed there when they were in operation. But Levin adds, wryly, “Later I found numerous old postcards of border crossings.” In any case, the optimism of the early 1990s has waned, and, the photographer reflects, what these images now show “is not so much the abandoned border crossings as our abandoned ideals.”

Maybe. For me, that idealism is hard to locate in these austere pictures—very straight, very clear. I’ve never seen a less Romantic vision of Europe. It is indeed a sense of abandonment that predominates but in a particularly eerie way: these structures do not look out of date, they are not in ruins—they simply look as if they’d been deserted from one day to the next. And not just the buildings but the terrain around them: the roads are empty of cars (though there are some parked here and there) and one catches sight only of a few rare human inhabitants, always at a distance. I have to imagine that Levin went out early in the morning, just after dawn, before people began heading to work, to find this unnerving emptiness. Some of the pictures encompass great distances, as if the camera were seeking out signs of life it could not find close at hand. Think, maybe, Giorgio de Chirico and Walker Evans collaborate with Rod Serling on a special episode of The Twilight Zone. So it’s a little unsettling when, in the book’s concluding essay (in French only), architect and theorist Luc Baboulet observes that these 30-year-old images “display the physiognomy of our present” and “also the conditions of a possible future.” Yes, it’s at the border that we have to answer Gauguin’s questions: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

But titles. I seem to be caught up, these days, in noticing how a word or two—On the Edge, Resurfacing, slowly, tenderly—can guide the eye through a book. So how could I resist with a title like Sex. Death. Transcendence.? I couldn’t help but think of Walt Whitman’s late word “A Clear Midnight”:

This is thy hour O Soul, thy free flight into the wordless,

Away from books, away from art, the day erased, the

lesson done,

Thee fully forth emerging, silent, gazing, pondering

the themes thou lovest best,

Night, sleep, death and the stars.

Mikael Levin, Au Bord, published by Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022.

Mikael Levin, Au Bord, published by Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022.

Mikael Levin, Au Bord, published by Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022.

Mikael Levin, Au Bord, published by Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022.

Mikael Levin, Au Bord, published by Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022.

Mikael Levin, Au Bord, published by Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 2022.

But Linda Troeller’s transcendence, her flight into the wordless, is more determinedly earthbound, more corporeal than was that of the “good gray poet,” her fellow New Jerseyite. The most recent of her many books over the past five decades, Sex. Death. Transcendence. is yet another beautiful production from Oakland, California’s, blessed TBW Books (2023). I am tempted to call it a book of self-portraits, but it might be more accurate to think of it as a single self-portrait in some 60 images: a portrait of the artist as a young woman and as an old woman, all at once, for the old contains the young and the young augurs the old. The middle, maybe, is missing. No chronology is given for what we see, though we can make our guesses. “Linear time, as well as categories of before and after, are disregarded,” as novelist Darcey Steinke writes in a concluding essay.

There is plenty of humour in Troeller’s anatomization of her own appearance, and of her odd fit with social roles. The knowingness is there in the eyes—when she shows them—the eyes that always say: There’s more to me, more to us, than this. Sometimes this is expressed through funny doublings (Troeller half-hiding, peeking out from behind a stone angel, only how can you hide behind something that already looks just like you?) or less funny ones (an elder Troeller with a terribly bruised eye staring out from below a painted portrait of the young one). And then there are concealments: the elder Troeller in the bathtub in a plastic hair cap and a paper mask that turns her into a sort of cubist portrait of herself, or the young one with big dark glasses and a spiky wig throwing deep shadow over much of her face as she poses, oddly, in front of a poster for missing children. What the eyes, when we see them, say: It’s that every appearance, even the one we might think to be the true one, is a mask—that something seen only through the eye, not of faith but of skepticism, transcends all this. ❚

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition “Jeff Wall” at Glenstone Museum, 2021. His new collections of poetry are Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022) and Water from Another Source (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2023).

Linda Troeller, Sex. Death. Transcendence., published by TBW Books, Oakland, California, 2023.

Linda Troeller, Sex. Death. Transcendence., published by TBW Books, Oakland, California, 2023.

Linda Troeller, Sex. Death. Transcendence., published by TBW Books, Oakland, California, 2023.

Linda Troeller, Sex. Death. Transcendence., published by TBW Books, Oakland, California, 2023.

Linda Troeller, Sex. Death. Transcendence., published by TBW Books, Oakland, California, 2023.