Snapped to Attention

Niagara Falls has been visited, viewed, gawked at, paid tribute to, mooned over, swooned over and turned to profit. Photographed over and over because it was monumental and astonishing, it has for these same reasons been reduced to fit on plates and keychains and pillows. With our looking we’ve risked exhausting this phenomenon and only the knowledge that we’ve fixed it through endless reproduction lets us rest easy in this time of Nature’s diminution. Similarly we’ve brought Mount Rushmore home, table-top size: no longer a topographical reality, it’s a monument to America’s relentless imprinting itself on the landscape. “Well, for heavens sake, look what they’ve done to that mountain,” or “All that water—who would’ve thought.”

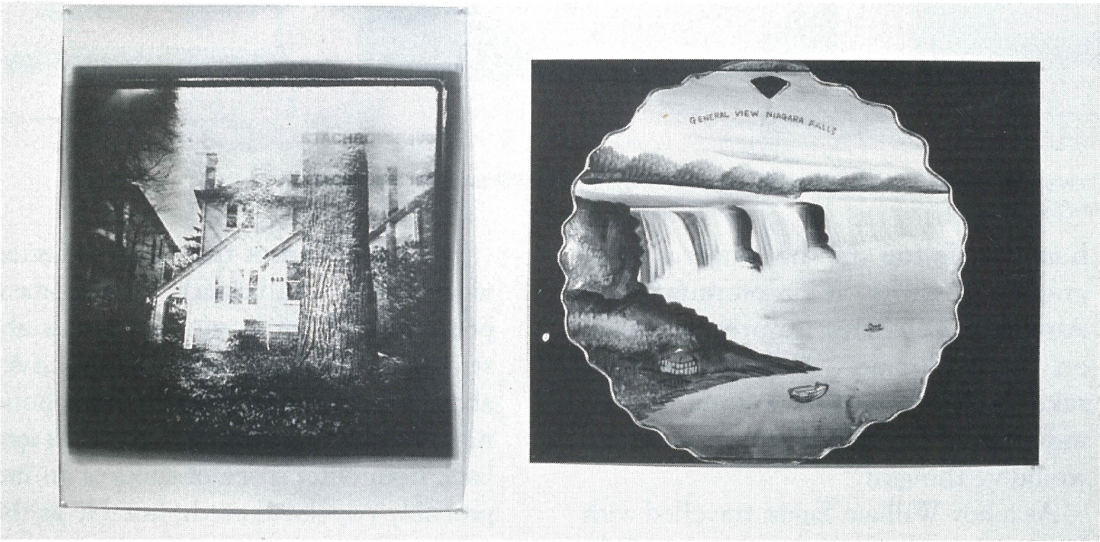

As a boy William Eakin travelled with his family on vacation to Niagara Falls and to Mount Rushmore. Powerful things, mediated forces of Nature and monuments to power were admired, were good things; it was assumed that these notions were shared and universal. William Eakin says he inherited these assumptions but he hasn’t held them and in recognizing they’re no longer valid he’s also recognizing their loss. There’s some nostalgia, he admits, even a little sentimentality provoked by looking back and letting go. But the sentimentality doesn’t wash into the photographs exhibited as part of Ace Art’s “Affinities,” a series of work by paired artists. Like Walker Evans’s American Photographs Eakin’s work is straight ahead and unembellished. The artefacts he photographs are garage sale, secondhand store, souvenir shop items, mass-produced and made of homely materials. Still, for Eakin they’re resonant and while he recognizes their lack of intrinsic value, he identifies what he calls a “stream of quality” in these objects. The photographs themselves are uninflected, a quality he achieves by neutral lighting, avoiding the manipulation of drama through this evenness. The drama, he says, comes from the objects themselves which are, for him, both heroic and autobiographical. They represent “not the good old days, just the old days.”

William Eakin and Sarah Crawley, “inside out,” installation,1995, Sarah Crawley; C-print, William Eakin; silver print. Photographs: Sarah Crawley/William Eakin.

In most instances the objects selected would have been brightly polychromed; presenting them as monochromes abstracts them. Shadowless, they hover above a deep black ground, a metaphoric night recalling the lunar photographs sent back from outer space or shots of an improbably populated earth, humble as the subjects Eakin chooses.

The exhibition’s curator, Sigrid Dahle paired a young photographer, Sarah Crawley, with Eakin for this show “inside out,” Crawley’s work being the “outside” into which Eakin’s “inside” could fit in loosely imagined narratives. She photographed worn and ordinary houses which could conceivably contain Eakin’s common, saved and decorative objects. Seeing them as metaphors for the self in that only the exterior surface is readily available, Crawley would walk up and down streets until some edgy quality, a feeling she described as uncertainty would call her to photograph a particular house. Whatever inherent merit or features drew her to her houses, what she did in photographing them was transforming.

Crawley used a Holga, a plastic camera fitted with a plastic lens (mail orders $14.99 USA). Essentially a toy, its rudimentary construction allows light to leak in and small epiphanies occurred from this technological short-coming. Flares as graceful as haloes resulted and there’s vignetting, with the light forming hazy brackets around the edges of the prints. Crawley says she manages these serendipitous effects through the editing. Sometimes the camera chews the film but the gift of enlightenment, this celestial quality, is something she pursues. Like Eakin, without dazzle or show, she elevates the quotidian and draws us in to look with fresh eyes at a world already over-represented.

Crawley’s printing is a multi-stepped process and with each stage there’s occasion for the images to become grainier, for the surfaces to be enriched by scratches and dust specks. Eakin describes her printing technique as an aging process which brings the physical manifestation of the print in line with the subject-worn buildings and burnished, discoloured prints coalesce. Both Eakin and Crawley describe themselves as painterly photographers in that neither pursues a reductive, formalist technique and while the work of both is based in reality neither is constrained or limited by it in a pure documentary sense.

Sarah Crawley, William Eakin, “inside out,” installation, 1995.

In a triptych Eakin’s is the middle photograph—a china plate with The Last Supper in an elaborate garland surround. He has cropped the top and one side, a subject too large to frame, reinforcing our awareness that it is a subject presented in a frame. On either side are Crawley’s photographs. One, an old greyed garage; the other a two-storey house with a chapel-arch doorway. A coherence of forms emerges: over Christ’s head in the centre photograph is an arched opening, on the left the garage’s gabled roof, on the right the gothic-arched porch entrance. Eakin’s subject is printed against a deep black ground; Crawley’s in a flare and blaze of light. Hers is a recessed space; his subject is pushed to the fore.

In another piece, a diptych, a mountain is altered to reflect a political hegemony and then further constrained by being imprinted on a china plate. Then Eakin crops it top and sides and still the breasts of the presidents swell with pride, barely noticing the fringe of pines that reach for their chins like arboreal whiskers. Crawley photographs a house that’s not special, not noteworthy—as modest as its photographic mate is grand. Self-effacing and almost obliterated by a flare of spongy light, its very ordinariness is a rational balance to Mount Rushmore’s intrusive and monumental kitsch.

While Eakin and Crawley had seen each other’s work, the real collaboration took place through the process of installing it. The pieces were edited and the numbers reduced. Loose poetic, formal and visual associations were made, and resonances and pairings emerged.

No one aspires now to the modernist directive to “make it new.” Photography itself is largely responsible for everything being over-recognized and too familiar—what can astonish us now? It’s unusual to find a contemporary exhibition of work which is uninflected by irony, which is neither quotational nor gratuitously self-conscious. In spite of the plainness of their subjects or perhaps because they’re unadorned and homely, the work in “inside out,” while not making it new, shows us instead that we can look anew. ♦

“inside out;’ William Eakin and Sarah Crawley, Ace Art, February 24 to March 18, 1995.

Meeka Walsh is the editor of Border Crossings