Sexy Boy

The Art of Cliff Eyland

Cliff Eyland is an art-world Imp of the Perverse. In Edgar Allen Poe’s formulation, the imp was “an innate and primitive principle of human action, a paradoxical something, which we may call perverseness.” The fit is a good one, as long as you understand that the term primitive has nothing to do with a lack of sophistication. It comes closest to meaning ungoverned, or, more accurately, ungovernable. As he says in the following interview, his attitude has never been to get people to accept his work, but rather, “try to stop me making this stuff.”

The stuff he refers to is a rich and varied aesthetic practice. Eyland is also promiscuously productive; he draws or paints every day—he has been known to complete 100 drawings in a single day—and now claims that he can make art as fast as he can sign his signature. He will also make art out of any subject for pretty well any purpose. He has placed over 1000 of his drawings in the Raymond Fogelman Library at the New School for Social Research in New York (the 1997 exhibition was called “File Card Works Hidden in Books”); he has done monochromatic “Brick Paintings” that look like what they’re called; “I.D. Paintings,” which include identification cards collaged into mixed media works; “Untitled Book Paintings,” which are painted to resemble small antique books with marbled covers and spines; and, most recently, computer drawings produced with the help of Adobe Illustrator. His subjects are as varied as the materials and media with which he chooses to work; there are fragile landscapes and A-Bomb paintings, classical figure studies and wildly erotic couplings, fantastic and surreal creatures of an unnamed future done in the same breath as demure and elegant ladies from an undetermined past. The only predictable thing about his work is that it is drawn or painted almost exclusively on blocks of pre-cut wood, or on filing cards that are 3 by 5 inches, a format he began using in 1981. Inside that consistent scale is a visual world of infinite, and sometimes bizarre, variety.

“More and more artists are becoming eccentrics,” is his comment on the art of Matthew Barney. If you take the meaning of the word as “being out of centre,” then it’s a description that suits Eyland’s own attitude towards art and art making. In all his activities connected to the art world—including his critical writing, curating and his catalytic role in the Abzurbs, the art band that almost never performs—Eyland regularly attempts to keep his various audiences surprised and off balance. He is genuinely attached to the eccentric. But beyond this willed instability, his attachment is to something else. In the following conversation he talks about the need “to exercise the lonely impulse of delight, which is so powerful that it will make people do the most amazing things.” This is criticism doubling as autobiography. Out of it emerges an image: Cliff Eyland, alone in his small studio, surrounded by 3-by-5-inch pieces of wood and paper filing cards, involved in the transformative activity of amazement and self-delight that we have come to call art making.

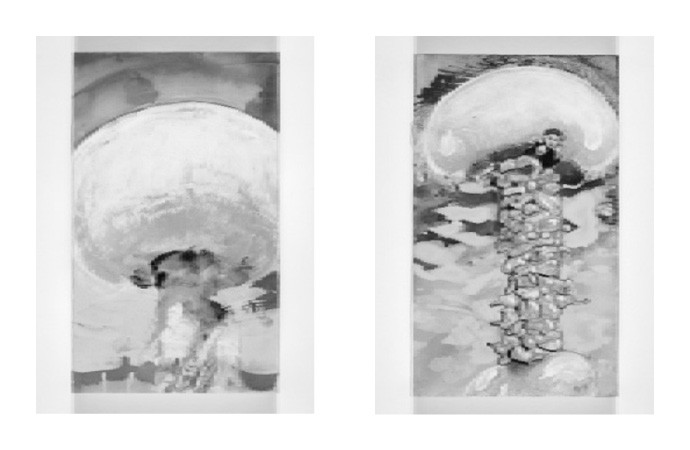

left: BRCR01, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”.

right: BRCR02, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

Photographs: William Eakin. Courtesy Leo Kamen Gallery, Toronto, and the artist.

Border Crossings: Tell me about the art band of which you’re a member.

Cliff Eyland: We have a band called the Abzurbs. I’m in it, and so are Dominique Rey and Tannis Van Horne, who are both artists. We’ve only played twice so far, once at Gavin Brown’s Bar in a spontaneous performance, which was really a picture-taking session of Tannis dancing on the bar—she’s a professional dancer—and more recently at aceartinc., where Dominique cut my hair.

I keep forgetting how varied is your artistic career.

It’s inevitable that you participate in all kinds of things because it’s a multi-media world out there. But the performances are not really part of my work. They’re a hobby. Mostly I make paintings. At one point when I was younger, I thought I’d have to give up art for painting.

Let me get this straight: the larger world is the world of art, and painting is a subsection of that larger world?

That’s the way people think of it now, but in the culture wars when I was a kid in art school, there were people who were fiercely committed to painting and if you had a talent for painting and drawing, you’d work with them. But their generational expectations of what was your commitment to painting was unsustainable as I was growing up. I’m talking about the ’70s. If you were a painter you would admit to yourself that painting wasn’t everything and maybe it was nothing. But I never had the resentment about painting that many of my generation had. I never had a chip on my shoulder. It really is just one medium among many. The only claim painting can make is that it’s immediately recognized as art by people.

Was there a point where you consciously decided that you wanted to work in opposition to the expectations of what painting was? If painting was big, you would work small; if painting operated out of a studio, you would work wherever you happened to find yourself.

Certainly the notion of an artist having a studio was something that everybody resisted. But there isn’t anything that I would have dealt with in my painting that had not already been established by the ’70s. All the questioning had been done by then and many artists—like Eric Fischl and Tim Zuck, who were around when I was a student at nscad—were approaching painting as if it were a blank slate. Certainly in terms of their skill level, it was a blank slate. I mean, these guys taught themselves how to paint and their painting is richer for it.

When you say blank slate, do you mean that they were engaged in a defensive strategy, that they weren’t prepared to deal with the implications of the debate about painting?

The blank slate is a reference to minimalist art. People felt that art had been stripped down to some essential level and they were going to start over again. When you do that, it makes for a lot of confusion because starting over always means that you have to deny the existence of related art movements or other vernacular forms—like folk painting—that are already doing whatever it is that you’re doing. The classic example is the effort by conceptual artists, not exactly to erase the history of Fluxus, but certainly to distinguish themselves enough to claim they were doing something new. The debate around postmodernism has made all these issues extremely complicated, and to unpack them I think you’d have to be an historian with a very good eye and a very fine ear. From my perspective, these things are pretty confusing to look back on. For example, how can you make cultural chronologies anymore? How do you pick a chronology when so much is happening? Maybe you can say that the conceptual artists and others responded to a panic by making claims they were starting from scratch. Maybe the conceptualists had to deny that George Brecht and Yoko Ono and the Fluxus people had preceded them. Maybe that’s a kind of panic reaction to the immensity of the world. I think that’s another reason why artists tend to identify themselves with abject characters; it’s very hard to sustain a monumentalizing myth about yourself. Or even to believe it. You know, our little strategies in the art world don’t often acknowledge the fact that there is the wider world, and that within that wider world the mythologies of the creator and the individual artist are so strong that they can’t be erased. These myths—like the myth of the struggling, individual artist and the cult of the genius—run deep in the culture.

left: BRCR03, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

right: BRCR04, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

I like the word you used earlier: unpacked. You make a lot of work and I wonder how you’ve unpacked the inherited complications of painting.

Well, I don’t have the baggage of the genius painter. Perhaps that was characteristic of my generation. I’ve never had the problem of agonizing before a blank canvas. And there’s this added idea from my art school Marxist youth that you’re “engaged in production.” So don’t get so uppity about your work. The other thing I’ve learned as a curator who has been able to visit vaults is how prolific some artists have been and how prolific you probably have to be. Think of Leonardo. You see a show and you see the 17 or so paintings that exist and you think, my god, his production level is so low, how could he produce so few things? But if you’d had a chance to see the Met’s show of Leonardo drawings, you’d be astonished at how prolific he was. He could make art as fast as he could make his signature. Me too, I’ve compressed my signature, which is a squiggle—and I think I’ve done that so I’ll take at least as much time making a piece as I will signing it. But I do have different kinds of work; some of them take a long time, some are dashed off. They also have different values and I’m interested in questions of value because some things I do sell quite well and are worth a certain amount of money, and other things I give away. I’ve realized that it doesn’t make a difference.

What do you mean, it doesn’t make a difference?

It doesn’t make a difference to the art market. I had this theory when Netscape came out—which has since been contradicted by the fall of Netscape—that you give some things away and you sell other things; I think that was Netscape’s model. I’m not clear whether that actually happens in art. There’s some weirdness about value in art that can’t easily be sorted out. It must give economists a lot of difficulty.

Does that mean that you don’t distinguish between a painting and a quick drawing you might insert in a library book, or leave on the street, or give to someone?

I suppose I could avoid that question by saying that the world out there is going to determine these values. But there are some conservation issues around my quick drawings on acidy paper with felt markers that will assist in that determination, whereas other works are more substantial and they’re done with archival materials. One thing about everything I do is that it’s made by hand. It at least has the look of art— and actually is art. Not only is it art but it’s immediately recognizable as such. So that’s a way of ensuring its survival. A tiny drawing that someone comes across in a library book might be preserved because it looks like a work of art. In the case of the paintings, it’s undoubtedly a work of art because everybody knows a painting is art. Sometimes I think of my work as being like that mole or shrew that sticks its head out of the ground once every 13 days as a way of avoiding the predator who’s looking for food every 10th day. Maybe it’s a matter of hiding enough, distributing enough and selling enough so that there’s enough material out there to be revived. Because, as a curator, I know it’s essential that enough actual work has to exist in order for an artistic reputation to exist.

And does reputation matter to you?

left: BRCR05, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

right: BRCR06, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

Obviously I don’t control that completely, but I do understand very well the mechanisms by which reputations are made, and know the certain dangers of the fabrication of a reputation. Artists are very clever about this stuff. What I’ve always wanted to do—and this might surprise people—is hover a little bit below the radar. Robert Hughes complains about Australia’s tall-poppy syndrome, and there’s a bit of that in Canada too. There’s a resentment of anyone who pushes too hard. Then, on another level, I want to be a civic and civil person, I don’t want to take up all the oxygen. It’s not necessary for me to do that. From the beginning I have deliberately rejected a certain kind of artistic persona: the one who is not engaged with other people’s art, who is involved only in writing about himself.

You’ve gone further than merely rejecting it; you’re a serious player as a writer and curator. You occupy space in all the areas of Winnipeg’s cultural production in the visual arts. Is that a reflection of how you feel an artist should operate, or is it simply an inclination of personality?

I think it boils down to painting and writing and all the applications of those things. There are lots of things people think are essential to current art practice, which I don’t do. I don’t make videos, for example. One thing I do that has become artistic practice is curating. But even there I came to a certain crossroads and decided that in my curating I was not going to be an artist. I was going to be outside the work looking in, and I was going to write about the work from the perspective of every person. Although I admire immensely impresario curators like Wayne Baerwaldt or curators like Andrew Hunter who are artists, I’ve decided I’m not going to do that.

You see curating in a more limited way than I do. When you curate—regardless of what is your attitude towards the act of selection—you’re making judgements that can have a profound effect on the career of another artist. Whether you have a disposition towards power or not, the curator’s role is extremely significant.

It is. The curator is an artist who uses actual artists as their artistic materials. Much to the frustration of artists, that’s the way curators think today. I have noticed, though, that artists with real status in our society can choose not to get that treatment and not to participate in a curatorial idea, and many of them do. I remember being shocked in the early ’80s when I heard that Jeff Wall had turned down participation in this New York show. I thought, what’s he thinking? But he was already at a point where he didn’t have to submit to curatorial conceits. So when I say that curators are artists, I’m saying they can only really treat emerging artists, or artists who are willing to submit. A curator who is an artist can’t do a Richard Serra show and decide he’s going to show the work submerged in a pool of water, or at the bottom of the ocean.

Unless he’s Matthew Barney.

I think Barney is a peculiar kind of genius, though. More and more, artists are becoming eccentrics and Matthew Barney is the ultimate eccentric for a certain generation.

The literal meaning of eccentric means to be out of centre. That’s just another variation on the kind of romanticism we were talking about earlier when the artist was the heroic outsider. Eccentricity seems to be a cut from the same bolt of cloth.

It is a myth and it’s only a matter of perspective. Myth still operates in the wider world and the myth with educated artists is material to be manipulated, because artists now understand media. Even kids coming into school are aware of what media is and how to respond to its tropes, its forms and its stereotypes.

Let me shift a little and talk specifically about your work. There are subjects that seem to appear consistently and I wonder if you’re aware of what they are and why they’re there.

I think I started really getting passionate about drawing as an adolescent because it was a way to see girls without their clothes on.

It was that straightforward?

I think maybe that’s true with a lot of het males. But, of course, the kids now have access to so many naked women you wonder if that impulse could drive someone to an art career. So an obsession with drawing for me is a metaphor for touching bodies, which you’re not really allowed to do. You can’t be like Rodin, you can’t twist your models out of shape and put them on a plinth. But the metaphor is still active. I’m always curious about photographers because I wonder how they deal with that tactility of flesh.

You raise the distinction yourself when you talk about the act of mark making as an equivalent to touch. For the photographer, it’s the eye that’s doing all the touching. So tactility isn’t really an issue.

Well, they do get to press a button, and when they’re surfing porn sites, people do click a mouse. So I would locate the eroticism of photography and of porn-surfing on the Net with the touch of a button by the index finger, which is bizarre because it would actually be so easy to track.

Is it a turn-on for you to make the drawings?

Absolutely. I’ll tell you why. As I get older, access to certain kinds of flesh becomes limited, but, like many artists, I can visualize three-dimensional beings in front of me without much problem. I rarely use models, but I can draw bodies without reference to them. So it becomes a weirdly interior world and a strangely masturbatory engagement, which is made real by painting. This metaphor of mark making as a sexual act is something that’s been going on for a long time. It’s ancient.

I didn’t realize making art was that physical a sensation for you. The work seems casual and that’s clearly not how it operates emotionally for you. Or is it just that you’re into group sex in a metaphoric way?

Yes. I’m always into group sex but only in a metaphorical way. This is the thing about our culture: no painting is going to have the erotic charge that people want, except Photoshop paintings. In other words, because Photoshop has made photography into painting, you actually have photographers who are engaged in that touch with the click of a mouse or with a graphic pad, which is so close to the tactile experience of painting and drawing. We haven’t really caught up to the fact that photography is painting now, but when we do, it’s going to hit us like a ton of bricks. People in the art world get it because we see the actual bodies and then we see the photographic versions of them, and we know the difference and get to fantasize all the variations. I don’t know if people in the modern world are really conscious of how constructed are the erotic images they see. But to get back to my initial point, I can’t imagine an erotic painting, as opposed to a Photoshop-generated image, working erotically in the way that people of our culture are used to. This will change and I’m sure photographers are complaining that video and the movies have completely taken over their function. But I will say this: I think a lot of fantasies are partly produced through photography by a kind of graphic art and drawing according to static poses and archetypes. I don’t mean that in a Jungian way, but archetypes of what we think looks graphically interesting. Which could extend to film. You can see this in supermodel posing; if you’ve ever drawn from a pose of a supermodel, you can see that one of the reasons why these bodies are so angular is because they present this clear, sharp, graphic language to the camera that can’t be presented by an amorphous form. It may not be a product of anorexia, it may not be a psychological syndrome; it could be graphic. It could be that an angular body presents itself to a camera in an especially pleasing way when the image is flat.

left: BRCR07, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

right: BRCR08, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

When I think of erotic images in art history, I’m interested in ones that are about restrained disclosure: Cabanel’s Venus, Bouguereau’s nymphs and all those 19th-century academicians who used classical mythology as an excuse to paint naked women. Is there anything left to be hidden or coy about in postmodern culture, given the availability of pornography on the Net? I mean, how does one paint the nude in a way that is still erotic when everything is available outside of painting?

You don’t conceive of eroticism as a practice that involves constantly upping the ante, you don’t conceive of it on the assumption that there are stages moving towards an ultimate image or an ultimate eroticism. You have to conceive of it in a complex way that allows you to look at Cézanne as being as erotic as Bouguereau. I’m fascinated with erotic issues around 19th-century academic painting. The whole notion of decorative eroticism presented in a way that wives and children can view it, but it’s coded as to be still erotic for the heterosexual male, involves a complex set of standards that only the French know how to pull off really well.

left: BRCR09, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

right: BRCR10, 2003, acrylic and/or oil on wood, 5 x 3”

What disposes you to make landscape paintings in which you’ve softened and almost pastellated your palette?

Lately I’ve been doing an awful lot of A-bomb paintings, which has to do with the boomer childhood I spent on airforce bases. I guess it came home to me because of the recent India/Pakistan conflict and because of the talk about backpack bombs. While the likelihood of nuclear winter is slim, the nuclear crisis isn’t really over. When I was a child, I heard my grandmother’s stories about being in the Halifax explosion and because of that I’ve had this awareness of the catastrophic bomb going off. I’ve also become interested in physics. I’ve discovered the reason why the atomic bomb was developed wasn’t because the American government had a lot of money, or because a war had to be won, but mostly because it was good physics. It gave these nerdy guys an opportunity to do some good physics and to exercise the lonely impulse of delight, which is so powerful that it will make people do the most amazing things. You know, that nerdy impulse to find things out.

Is painting an aspect of that same nerdy impulse?

Yes, but in a different way. It’s anachronistic and archaic; that’s how it’s nerdy and it will be permanently so. I’ve been thinking about Guy Maddin’s films a lot because he’s a Winnipegger and at one point I thought, maybe I’m more archaic than he is because as much as he’s obsessed with the early days of film, there’s an older and an even more anachronistic medium than film—and it’s painting.

I assume you work on a number of panels at the same time. Do you sit down and work on a regular basis?

I make a drawing or a painting every day. While that may seem a neurotic or compulsive thing to do on one level, it’s not any more compulsive than being a fry cook, or going to the same job every day. It’s probably a lot less compulsive than what most people have to deal with. I have quite a bit of latitude about when I do these things and, strangely, I’m finding that the more anxious and worried I am about things, and the weirder things get, the more art I make. So that’s definitely an indicator that it’s a bit compulsive. But it’s not compulsive in the way that Robert Crumb’s brother would get into a kind of graphical mania and fill pages and pages with incomprehensible text. I never forget that these things are going to go out into the world and they regularly do.

So you’re not a psychotic, outsider artist?

Well, it would be silly to say that because I have a certain pressure from the outside world to make work; I have shows coming up and people are interested in having these things, so you can’t really call it a compulsion in a psychological sense.

Does it please you that people want the work?

Well, my attitude has never been: please accept my work, or please accept me as an artist. It’s always been: try to stop me making this stuff; try to stop me from being an artist.

Do you find yourself more compelled to make paintings now than you did even a decade ago?

I’m more productive now because I’m financially secure. That’s weird, isn’t it; I make more work because I’m neurotic and anxious and I also make more work because I’m financially secure. But a lot of the stuff I make disappears into libraries, so it’s not going to turn up for a long time. It’s not as if I’m down everyone’s throat all the time. I have a dealer in Toronto, I show in public galleries, but I’m not taking over the world and I have no ambitions to do anything like that. It’s more like hiding myself in the world. I’m not aggressive, I’m not trying to dominate, or to get people to see the world my way. None of that interests me. Everybody’s got the capacity to look at the world in a unique way and they don’t need my vision to help them out. Actually, I don’t think artists are especially great at that. Artists get on jags that seem to be totally derivative but most artists I know are actually really capable people. In other words, the players in the art world could have decided to be players in any world. It’s surprising how often in my conversations with other artists what comes up are things they turn down. As someone like Sartre would have said, their engagement is in the quality of their refusals. Their compulsions are one thing but their refusals are very important too. The big thing they refuse to do is to spend time doing something else, because art does not really cost money to make. You just need time to make it. As we know from our young Winnipeggers, you don’t need a lot of materials. You can make spectacular art right out of the dumpster.

What about the role photography plays in your work?

I’m best known in Winnipeg’s underground for assembling people, getting them a bit tipsy and then persuading them to take their clothes off. It’s a cheap way of getting models. I should add that all my photographic images are heavily Photoshopped, cropped and, in a sense, digitally painted. But I’m close to some very good photographers—like William Eakin—and after talking to them for five minutes, you realize they’re in a completely different world. They think deeply about things—technical and aesthetic issues— that you don’t really think about at all. I also know that many photographers are a bit resentful at being pigeonholed as photographers. It seems like every medium is insecure nowadays.

Do any of your photographs become the subject matter for the paintings?

No. The paintings are always made up and the photographs are always from some documentary situation.

Why do you bother with the photographs?

I didn’t bother with photography for years because it was too hard. There’s a certain necessary technical engagement and one of them is being in the darkroom. I spent three days in art school in a darkroom and that was it for me forever. So there’s a certain technical engagement with which I can’t get involved. I say it’s technical but it actually has to do with a photographer reading back through the technical ways this thing has been created. I’m thoroughly comfortable with tracing back to its sources the technical construction of a painting, but with photography and cinematography there’s a different technical read and that means a different engagement. But the point is, I am engaged. ■

Order Issue 88 here.