Self-Solving

The Enigmatic Art of Nicola Tyson

Had Nicola Tyson been born in the 16th and not the 20th century she would have been a cartographer, mapping her passage through space by drawing the people and creatures she encountered in the course of that transforming journey. Looking at her drawings puts you in mind of late medieval artists who had heard reports about land and sea creatures, but had never seen them. So they imagined what they must have looked like. The result is a bestiary of fabulous animals—sea swine and devilish serpents and armoured herbivores—with horns and beaks, spiked tails, webbed feet, formidable jaws, furry scales and elaborate plumages.

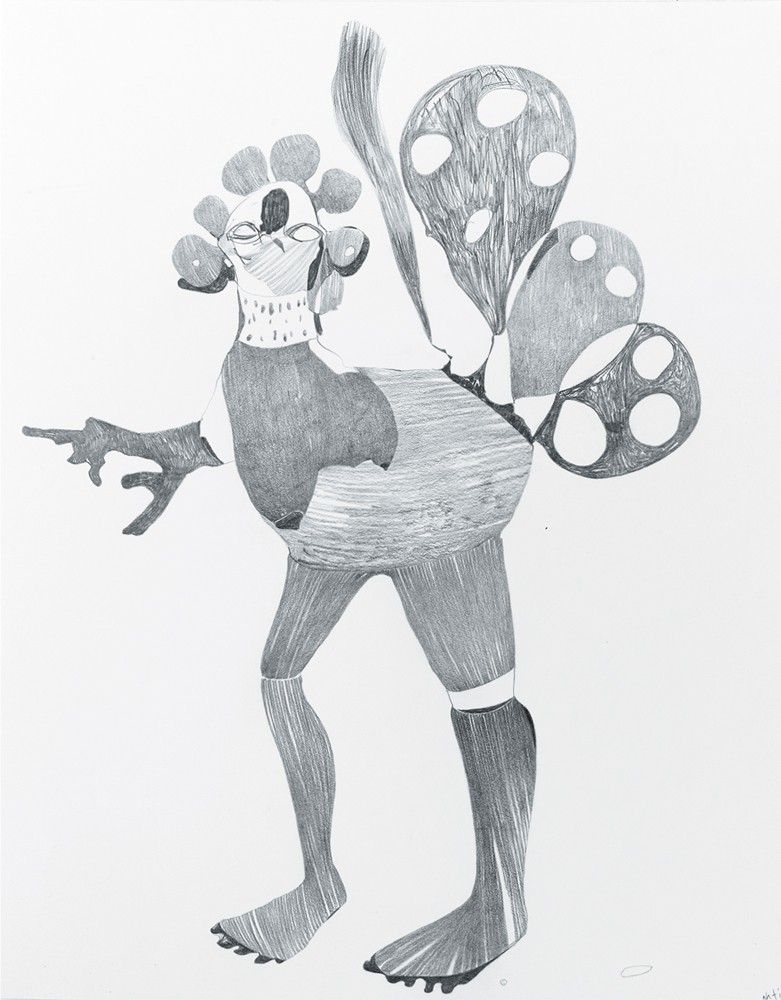

Tyson’s animals and humans are similar hybrids that find their form and character in the act of being drawn. Graphite Drawing #19, 2014, shows a figure striding forward and gesturing towards another smaller figure in the distance. It appears to be an image of loss and imminent longing. The back of the main figure is an intricate carapace, as if Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut of a rhinoceros from 1515 had leaped ahead in time, leached out the colour, but retained the pattern of a Gustav Klimt painting. Dürer never actually saw the animal he rendered, but it remains convincing today. Tyson saw her figure only after she made it, and it is equally persuasive.

Nicola Tyson, Head #9, 2016, acrylic on paper, 24 x 18 inches. All images courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York.

As a child, she was a sojourner in nature, a bird- watcher and a breeder of butterflies. There is evidence of that experience in her art; she has drawn hefty butterflies beginning their migration and painted a self-portrait depicting herself laying an egg. From her earliest exhibitions, the bodies of her figures have assumed the posture and gestural qualities of animals, birds and other flying things. They perform rituals that include peculiar courting dances and flashes of awkward peacockery. She has a sense that she is on some kind of continuum with animals. “I don’t feel separate,” she says. “There is a boundary-dissolving thing that goes on in the work, where people become plants and landscapes become people because I like that feeling of merging.”

Tyson’s birdly creatures are amazing creations: the bird in Sketchbook #28, 2005, has the plumpness of a partridge, the webbed feet of a duck and a hat with a black shark fin; in Graphite Drawing #16, 2014, it has a nippled breastplate, a three-part fanned tail with a whisk, and gartered leggings that turn into spats. Her animals and humans are fancy; they are aware of how they hold themselves in space. So the figure in an ink-on-paper drawing called Great Pants, 2016, wears exactly what the naming describes, a pair of bellbottoms of stilting attenuation. In her most recent self-portrait Tyson sports a red tie as large and solid as a cricket bat.

She talks about drawing as “mapping around with a pencil” and she describes her overall approach to composition as “mapping this very delicate dance where consciousness enters matter.” This process is one that she generates from the inside out; her psyche needs soma to which she then gives form. She makes it matter, as both material and conviction. “I wanted to come up with a new way of looking at and representing female subjectivity because there wasn’t enough of it.”

Head #8, 2016, acrylic on paper, 24 x 18 inches.

She was mapping a kind of void. “I started to draw a female body from the perspective of having one rather than looking at one, it being my home.” Her wilful cartography has resulted in a pictorial language of unique form and intense detail. Her engagement is not only with shape-changing but with shape-making. It is a pictorial world that is in constant flux. “I’m bringing these momentary things to life,” she says about her bodies, “they’re really just fleeting arrangements that are literally caught. In the next frame they are going to shift into something else.”

When we look at Tyson’s painted and drawn figures we are apt to agree with Miranda from Shakespeare’s Tempest, who exclaims, upon first seeing a man, “How many goodly creatures there are here.” Enchanted by a benign and brave new world, she wonders at “How beauteous mankind is.” Nicola Tyson discovers herself in a new world of her own making, too. But from her perspective, it is womankind who is beauteous.

In 2005 she exhibited Nude, a large 75 x 54- inch oil and charcoal on linen painting. The figure stands in profile in a yellow space that seems saturated by sunlight. She is tall and thin and full-breasted and she raises her hand into a mass of grey hair that rests on the top of her head like an animal pelt. Her form, while lumpy and irregular, embodies a kind of craggy lyricism. Stripped of everything except her unadorned being, she is magnificent.

Nicola Tyson’s first American survey was on exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis from January 27 to April 16, 2017. In late September a show of new works on paper will open at The Drawing Room in London, UK.

Nude, 2005, oil and charcoal on linen, 70 x 54 inches.

The following interview was done by phone to New York on Sunday, January 15, 2017.

Border Crossings: In your letter to Gainsborough you mention your “fevered suburban childhood.” Do you want to flesh out what that childhood was like?

Nicola Tyson: Well, a suburban childhood back in the ’60s was quite different from what one would be like today. We didn’t have cell phones and social media, so you were thrown back on entertaining yourself. As a result, I was dealing with my own fevered imagination, without much distraction. And of course, the nuclear family was very claustrophobic. Ours was the classic two-child nuclear family of the ’50s and ’60s living in suburbia. My dad was an engineer and my mother was a teacher so I didn’t get much exposure to art. Instead, there was this family interest in environmental issues and going out walking and birdwatching. I thought that was going to be my vocation and then everything changed when I became a teenager and discovered pop culture. In the mid to late ’70s in London there was an emerging punk scene and I got thoroughly involved in that. I discovered I was actually more drawn to art and that my skills as a child, drawing in a mimetic way, could be used for things other than reproducing reality, which was what I had been applauded for when I was a kid.

In your Manet letter you say that the only prize you ever received was for a set of bird drawings you had done for the Young Ornithologist Club.

Which is funny because that kind of thing emerges in the hybrid characters that I draw, in the weirdness of birds’ feet and beaks. You can see those odd formations in my work.

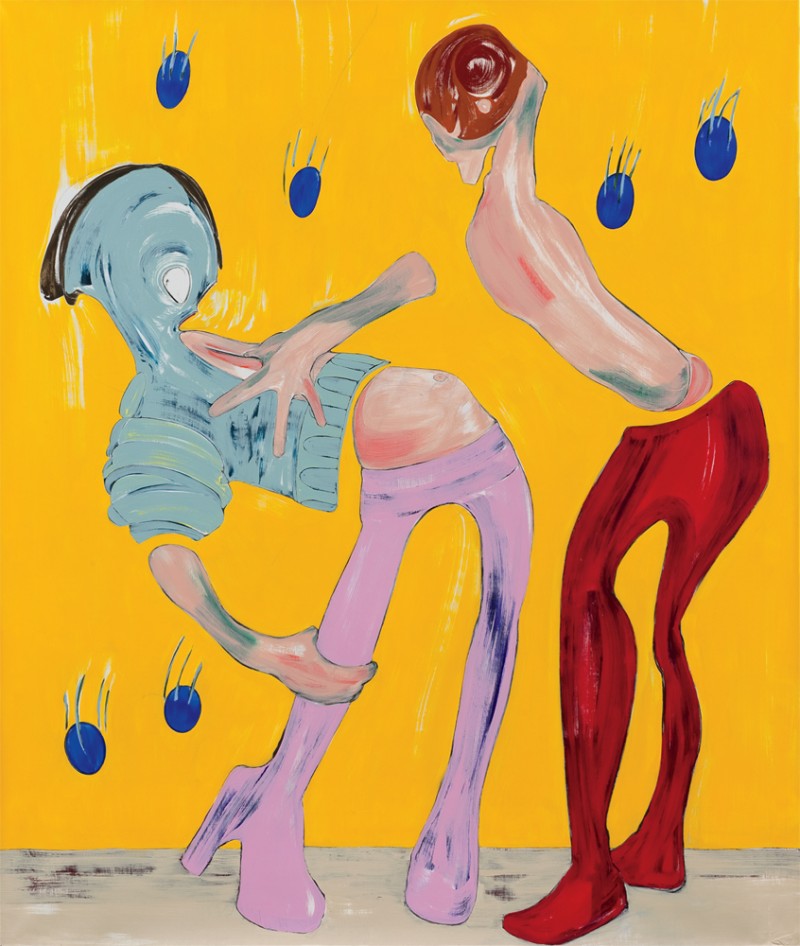

In a piece like Self-Portrait with Friend it looks like we’re observing a bird-mating ritual.

It’s true. When I paint I don’t set out to say any particular thing, and if I don’t know what’s going on in the paintings, that’s when I’m satisfied. If it’s enigmatic, I don’t push to find out what it’s about. I simply go with it and when people say things like you just said, then I see what I’ve done.

Self-Portrait with Friend, 2011, oil on canvas, 72 x 95 inches.

Is all your work operating in a similar way in that you don’t have a preconception about what you want to do, and that you find the work in the making?

Very much. I just start working with the pencil. The paintings are much more deliberate because once I’ve got a drawing that I want to use, I will project it carefully onto the canvas, and what follows is a much slower and deliberate process of fleshing out the image with colour. When I’m drawing I purposefully work pretty fast to lay down the energetic structure of the drawing. Obviously, the shading and cross-hatching takes time afterwards. But I do the initial downloading very quickly, so that I don’t intervene at any point and turn it into a contrivance. I always want to be surprised at what pops out, so I stay out of the way. It comes out of my hand and not my brain. I’m there to guide it around.

In the small drawings you set the condition that you have to finish each drawing in one sitting. Is that another way of guaranteeing that it doesn’t become too conscious?

Great Pants, 2016, ink on paper, 72 x 42 inches.

Yes. The “sketchbook drawings” are in my ideas book. The rule is I would never go back into them. So the sketchbook drawings would be done pretty quickly and left unfinished, and then some could be developed further and turned into paintings. Others felt like they were finished.

There is a 7.5-inch square drawing called Hefty Butterflies Begin Their Migration from 2015. Is that a finished drawing that came out of a sketchbook idea?

That was a different set of drawings that I did last year and into the year before. I decided I was going to put quick drawings on Instagram every day as an experiment to see how that works, having held off from that type of thing for a while. I started posting a lot of existing sketchbook drawings that I was scanning. But then I bought this square sketch pad and every once in a while I would do a fairly finished drawing. As they were coming out, I seemed to want to do a lot of shading, so they had a slightly different feel. Of course, that butterfly drawing hearkens back to my relationship with creatures. When I was a kid I used to breed butterflies, and I was very involved with caterpillars. I feel close to butterflies. There is the added joy in how much you can conjure up using a pencil. The pleasure of the pencil is that it can register so many different things.

You have said that when you’re drawing you want to be surprised. But you have also mentioned that you want to be unnerved by what you make.

Sometimes I can look at them and have no idea where they came from because I don’t plan or rehearse the drawings in my head. This came out of a period in art school in the ’80s when I got quite involved in feminist theory. It was amazing and life-changing. For a while I veered away from painting and was obsessed with how I could work with these fascinating theories that had opened up for me how the world works. Then I got stuck in a dead end because I found myself trying to illustrate these theories.

Figure with Sphinx, 2011, oil on canvas, 72 x 72 inches.

One of the concerns of ecriture feminine was to “write the truth of women’s bodies.” Did you take that literary idea and apply it to the visual arts in deciding that you wanted to paint and draw the truth of women’s bodies?

In the end I was battling this straightforward basic feminist thing of how men had represented women throughout art history. Nowhere was female subjectivity represented, and while I had analyzed the apparatus of my own oppression through reading these texts, I couldn’t illustrate them. It seemed simplistic but I thought, why not empty out everything from my head, dig around, and see if I can map that void and come up with some figuration that is free of those pre-existing coordinates? I began with a pencil because it was diaristic and it was very easy to move fast and experiment. I started to draw a female body from the perspective of having one rather than looking at one, it being my home.

It occurs to me that one of the things you do is to show this inner female void by depicting, even displaying, the female outer. I’m intrigued by your understanding of the relationship between the interiority of women’s consciousness and how it becomes externalized in images, figures and portraits.

It’s trying to draw your body as you feel it, and like in a fever, certain emphases are different, so you might feel you have gigantic hands. But if my psyche is this set of coordinates occupying my body, when you start to draw it doesn’t come out with the normal exterior contours. The coordinates are constantly changing and always shifting because you are thinking and feeling in space, rather than being an object in space.

Quarrel, 2014, acrylic on unstretched linen, 85 x 71.5 inches.

You mention big hands and I notice that they appear often in your paintings and drawings. Why is that?

That comes from a deep sexist issue. When I was coming out people like Baselitz were saying that women can’t paint and that you need a dick to be a painter. For me it was not a question of needing a dick but needing hands. So as a woman artist the hands take on a special importance. The hand is the real tool.

Your self-portraits are delightfully varied; you have painted yourself as a sphinx, laying an egg, in red and yellow, and recently wearing an audaciously large red tie. Is making a self-portrait different from doing a painting that doesn’t use you as a subject?

A lot of the work is obvious self-portraiture and that’s where the humour comes in. There is usually one of these absurd images in every body of work. It is awkward to be wearing this giant red tie given the political climate here in the United States, but I wore a red tie at school with my uniform, so that’s what it’s referring to. There’s also my androgynous relationship to clothes because when I was a kid I thought I was a boy, and I spent many years as a child dressing and passing outside of school as one. It was only in my teens that I decided I was going to embrace being a girl. All that is normal now, but back in the ’60s and ’70s there was still an element of transgressiveness in cross-dressing. It wasn’t mainstream, if you know what I mean.

You say that fashion keeps creeping in to your work. The character in Drawing # 4 has very smart trousers. There is a consistent sense of bespokenness about the clothes in your work.

I love bespokenness. A few times in the past when I could afford it, I have had suits made. There is something very reassuring about the external structuring. It is this very physical relationship to tailoring as opposed to a fashion-y thing. It fascinates me the way tailored stuff embraces you and so closely follows the contour of your body. If you look at my work, hardly anybody is ever truly naked. There is always some little bit of clothing, which makes the nakedness more naked. In Schiele’s work, for instance, especially the more pornographic images, the models often kept some clothing on because that was more titillating. I’m a very conservative dresser myself but I did hang around with people who dressed more flamboyantly. I had friends in fashion and when I was in art school, St. Martin’s was famous for its fashion department. So that element was always in the air. I’m amused with the mixture of dead seriousness and utter frivolity. The other extreme from the bespoke in my figures is that underwear or baubles or little frills often appear. When you start to get frilly things and bits of skirt they often feel like extensions of the body. The skirt thing is always big for me because as a child I was a tomboy and would never wear girls’ clothes, and I couldn’t understand why anyone would even wear a skirt. It seems so vulnerable and weird and impractical. But the frock and the skirt pop up a lot in my work because they hold some sort of alien fascination.

Graphite Drawing #19, 2014, graphite on paper, 24 x 19 inches.

The graphite Drawing # 19 is an image with a figure leaning forward and the entire back reminds me not so much of Schiele as Klimt. And in a drawing called Untitled # 2 from 2013 there is a Klimt-like bib with an epaulette on the shoulder. There is a sense of design or patterning in these clothes.

I like words like “bib” and “frock” and “frill.” They make me want to draw, actually. I also like sticking in little passages of pattern. I want my figures to have something like that going on. They are completely lacking in authority. It’s a mixture: sometimes authority will be referenced in epaulettes and little uniforms, and at the other extreme there will be pyjamas or bibs.

It’s like your drawings have attitude. They often seem to be striking poses. They have good posture or something.

Definitely. There is elegance and the humour comes in with the attitude and posturing. When I decided I was going to stop fitting into any existing rules, the playful aspect became very important.

Let me give you an example that comes less out of fashion than art history. I was struck, in looking at Untitled Tall Drawing #1, how similar the pose is to Donatello’s David.

It wasn’t conscious but that may well be. I’ve always enjoyed Greek kouroi and that period of sculpture. My best friend is Greek and I love going to the museums in Athens. That’s where all that sphinx stuff comes from; there is a sphinx in the Metropolitan Museum here in New York that never fails to hit me. It’s so alive it looks like it’s about to jump off the column.

So does the sphinx in your painting called Figure with Sphinx from 2011.

That is definitely related to the work in the Met because that sphinx just keeps giving. I can’t get enough of it. And I like mixing up all the gendered stuff. I like the potential feeling of having wings, or being that creature. I can really identify with some of those mythical creatures.

It is interesting how often the animal sneaks into your drawing. Untitled #2 has a rich textured head and dark eyes, and in Untitled #4 the figure looks vaguely dog-like. Those drawings look more animal than human.

I don’t have a plan so it is unconscious, but I do enjoy the sense of being on some kind of continuum with animals. I don’t feel separate. There is a boundary-dissolving thing that goes on in the work where people become plants and landscapes become people, because I like that feeling of merging into other things. Also, it becomes part of me, so when I’m mapping around with a pencil it is like this seismographic thing that I’m connected to at that moment. It can turn into an animal or breasts can pop up in unlikely places.

Standing Figure #6, 2016, graphite on paper, 39 x 25.5 inches.

I notice in your sculpture you are finding pieces of wood, and in becoming figurative objects they look like three-dimensional versions of your drawings.

The sculpture was something I could do because it was easy. It was there and I actually enjoy making things. When I was younger I made things more than I drew, and going forward I would like to make more, so this was an excursion in that direction. Finding these figures in a pile of wood was a bit like making a drawing in reverse. I knew there were drawings in there and I had to find them. So doing that sculpture refreshed my relationship to my work. It made me get back in touch with this fundamental conjuring up of people and things out of nothing.

Do the drawings tell you where to move more than you decide where you’re going?

Yes. It happens in the paintings as well but on a much slower level. That’s when it gets to be fun. At a certain point a painting will start to solve itself and you just have to show up and be told what to do. With the drawings there is a point, once I’m into them, where it is literally a conversation with the thing that is being drawn. It’s not like I’m completely in a trance, but I work so quickly that it’s ahead of me.

But it’s not automatic drawing as the Surrealists practised it?

No. Decisions are made but they’re done quickly. So, for instance, I’ll decide I want lots of hair. I couldn’t do the kind of drawings I do if I sat down and slowly planned them out. They wouldn’t have that life; I wouldn’t make those discoveries.

What was it that made you decide on the epistolary form in the letters to dead male artists? They are a rich combination of art criticism, manifesto and personal exploration.

The whole project started accidentally because Nicole Eisenman and AL Steiner were organizing these provocative shows every now and then under the title “Ridykeulous.” Back in 2011 there was one they called “The Hurtful Healer: The Correspondence Issue,” and they invited all sorts of artists to write a letter of complaint about something that was bothering them. That’s when I wrote that first letter called “Dear Man on the Street” about being told to smile. Back then people weren’t thinking about that too much, whereas today there is a lot of discussion about being harassed on the street. I realized I had a lot to get off my chest, and I wrote these letters as a cathartic, humorous exchange with a friend. I read them aloud and I enjoy performing them. But they are characters; they’re not me.

That’s an interesting distinction. Novelists will remark that a character can take over the story. The writing writes itself. Does that happen in the letters as well?

Graphite Drawing #16, 2014, graphite on paper, 24 x 19 inches.

Yes, that’s why I sign different versions of my name; some of them are formal, some are flippant. The Picasso is just signed “Tyson.” They are types that are doing the talking. I wouldn’t say any of them is really me.

You dismiss Lucian Freud, referring to his “horrible, redundant and fucking claustrophobic painting.” What was it about him that got under the skin of your letter writer as much as it did?

It really goes off on a tangent, doesn’t it? When I was in London back in the ’80s it was a very small art scene and it was male-dominated. We had these big figures, Freud and Bacon, and it was enraging how revered Freud was. He famously had loads and loads of illegitimate children everywhere, and there was this whole permission that wasn’t available to me as a woman. I also didn’t think the work was that great. It was somehow all very British and I wanted to escape that mindset.

So was your move more about leaving London than it was about coming to New York?

Right. I couldn’t wait to escape.

Both Marlene Dumas and Cecily Brown have dealt with this question of male influence in the depiction of the female body. Brown’s is a strategy of engagement rather than one of rejection, which is closer to your approach. Your reinvention of the body moves away from Bacon and Freud.

For me it was a question of getting as far away as possible from that admired mimetic thing. I was bored by the idea of the body as a lump of meat. I decided I had to come at it from a completely different angle. On the other hand I love Bacon’s work, and I enjoyed the way that he and Freud played off each other. Freud embodied everything that I couldn’t stand about British art, whereas Bacon had spent many years in Germany and had been living this life before he started painting. He had even been a designer. He brought so much sophistication to painting and I don’t know where British painting would be without that.

In your letter to Bacon you want some of his “nervous system stuff.” You joke about your SM relationship, but you clearly looked very closely at him in your early years and learned that you could transfer psychic intensity onto the surface of the painting.

Absolutely. Bacon was reinventing the body and I definitely looked at him. He loomed huge over everybody of my generation, and for some time afterwards, because he busted out of all that British stuff. In a weird way even artists like Damien Hirst, with the sharks in tanks, were doing a version of Bacon. Presentation was important to Bacon too—he insisted his work be framed in gold and behind glass.

You have a rather lyric description where you say that for you, as opposed to Bacon, “flesh and consciousness are locked in a playful delicate dance.” Dance is an activity that comes up very often in your work.

It’s a question of figuring out what’s going on and mapping this very delicate dance where consciousness enters matter. It’s a strange and temporary relationship, because my body is my home but I’m somewhere else too. I’m engaged in this odd and disorienting relationship to what being in a physical body is. I’m more interested in that, which is of course mostly invisible. I’m trying to explore and map and get imagery for that, rather than dealing with the meatiness of it all.

You’ve said that there are no edges between you and everything else, which makes me think that your body and psyche are in constant interaction, one that I suspect is sometimes discomfiting. It’s like being too alive; the inner and outer and the surface and the interior are too close.

It’s all about these boundaries: where do I begin and where does the rest of it end? That’s what I mean about the body not being a recognizable machine that I move around in but that flows out in all directions. It doesn’t feel that it necessarily stops where it stops.

Dancing #3, 2012, graphite on paper, 50 x 30 inches.

Was Cindy Sherman a game-changer for you, because in the ’80s she did what she liked with her own image and gained authority over the depiction of her body?

It was also that she was playing. Making art is essentially playing, and it was hard for women to have the creative authority to play and be seen as meaningful at the same time. I was a painting student in the ’80s when Sherman was presenting herself as these crazy individuals, either in proper portraits or lost in some strange mess that she had created. It was so liberating because she was playing with images of being a woman and she was taking on the representation of women in photography and fashion. It gave a huge amount of permission and helped me realize that I could play at what it is to be a woman. But I would do it with drawing. When I first exhibited back in the ’90s, she bought some of my drawings because she recognized a similar investigation. That was a great moment for me because she was my hero.

You talk about your quest for authenticity and I want to get a sense of what that means. You refer to your relationship with authenticity as “almost neurotic.”

There is a bit of exaggeration in those letters but I did have a real obsession with my true self. I literally went through a period where I abandoned all exterior rules, theoretical or otherwise, and stopped looking at anything for quite some time in order to clear out my head. I wanted to see if I could come up with something that wasn’t influenced too greatly and that only I would come up with.

You have gone some distance in reinventing how the female body can be rendered. Was pictorial reinvention, which is really another way of talking about originality, what you were after?

I was this woman who needed to dig up some information that I felt would be relevant to the argument. I knew it would have to be authentic in some sense. Yes, I wanted to come up with a new way of looking at and representing female subjectivity, because there wasn’t enough of it. I wasn’t seeing it anywhere. I felt—and still feel—that a huge amount of information remains to be brought to the table, as it were.

A review in Artforum of your last show at Friedrich Petzel in New York refers to the “tender grotesque” in your work.

I was struck by that observation. I like the use of the word “tender.” I thought it was insightful, because a lot of the time people will see the work as angry or too focused on the grotesque, or collectors will say that I like a work but it has no legs and it makes them think of amputation. They have no problem with the classical torsos in museums that are missing arms and legs, but when I decide to not bother with limbs it gets misread. But the tender thing is true; it is tenderly done and legs are not necessary. I don’t do it as an act of violence.

It’s not what Bellmer does.

I looked at a lot of Bellmer and while I don’t like all of it, I find his work fascinating.

Your work can be argumentative, to use one of your own terms, but the violence that occurs in Bellmer is not something in which you seem to have any interest.

I’m not doing the body that is being consumed. His bodies are penetrated with these endless, elaborate holes. He’s making his work from a completely different perspective than mine. My bodies are not to be used and penetrated. I’m not mapping my desire all over them. I’m just bringing these momentary things to life; they’re fleeting arrangements that are literally caught. In the next frame they are going to shift into something else.

There is something about the ambiguity of reading your work. In a graphite drawing called Falling or Floating (2015) you bring that double reading to the viewer’s attention. I gather the ambiguity of not knowing is something you want the drawings to embody?

Couple Dancing, 2013, acrylic on linen, 85 x 71 inches.

Yes. I like to feel that when I’m looking at them. It excites me that in painting and drawing a lot of things can be going on simultaneously. I title after the fact, so once the drawing is finished I get a chance to see what has happened.

The drawings are invented figures or characters but they also seem to be attitudes and emotions that have found a form through the body itself.

That is absolutely true.

Do you ever start out drawing angrily?

Sometimes there is anxiety when I start drawing and I get an agitated image. A lot of them are disturbing and not “tender” in a straightforward way. But they develop emotionally. I might start out with an agitated image but then put in some ornament before leaving.

Do you find it easy to go into the studio?

It’s quite a struggle to get that image, and it’s not always available. You can sit down and draw and nothing happens, and then there can be spurts. There will also be periods where I’m painting and won’t be drawing much at all. There are only so many problems that I can hold in my head at a given time, so if I’m absorbed in trying to solve a painting I won’t have enough left over to suddenly do a bunch of drawings. I have to bring them down or up from somewhere and that does take muscle.

Your “Tall Drawings” are particularly compelling. Was it a series you set out to do?

Generally I have done series. If I decide on a paper size it will be with the idea to at least do a small series. Those tall drawings were an opportunity to stretch the image to the limits of what I could handle quickly. You get the basic entity down and then there might be some leisurely shading that goes on afterwards. But it had to be within the sweep of my arm in order to get the energy I wanted. That’s why I tend to not draw directly onto the canvas, because it is too big to get that sweep; it is better for me to work on a smaller scale and then project that onto the canvas. I can’t physically capture an image that large; it’s too big an area to manage.

In Tall Drawing #5 you stack the component parts of the body in widely divergent scales, so you get a big foot and a little head. It actually shows the process of how a drawing could be constructed.

It’s fun to do this kind of stacking with unlikely scale changes to see if I can still pull it off. And to see how far I can go before it doesn’t hold. I don’t chuck a lot of drawings away. I do little batches of them and there is usually something useable, even if it’s just an idea for another one. There will often be some aspect of a drawing that has life, and as long as there is a kernel of something, I can build on it later. But I have to get the life breathed into it right away.

In New York in the ’80s you’re wearing a Jenny Holzer baseball cap saying “The Future is Stupid.” What would it read today?

I wish I still had that cap. It still does it. I had two of those caps and the other one said “Protect Me From What I Want.”

There is something in your work of what James Gillray, the 18th-century satirist, calls “mock-sublime mad taste.”

He said that tendency was particularly British and described it as pushing through satire to anarchic freedom. That kind of humour is very much in British culture and it comes out in everything from punk to club characters like Leigh Bowery. Another thing I needed to escape when I left London was the British horror at seeming pretentious. It is a terror, so it tends to squash passion, which is recognized as dangerous. The emphasis is to be entertaining and to laugh at yourself, but that can get in the way of serious artistic endeavours.

In your writing you made me aware of the complexity of contemporary art. When you divide the word into the “con” and “temporary” because it won’t last long, it opens up a whole new critical perspective. You call it “that self-strangling primitive death-throe art that is going on.” Are you as cynical about the state of contemporary art as your parsing of the word implies?

Occasionally I get a bit exasperated with art where you read the press release and then you look at the props. I want more from an art experience. The state of art can sometimes make you feel despondent and apathetic and other times it can be motivating.

Were you ever tempted by abstraction? I know you call it “mutton made by a bunch of sheep.” Is that the persona of the letter writer and not you?

That is totally the persona of the letter writer. But I have never been drawn to abstraction. I feel that all the moves have been worked out; it’s a game, and you either do it really well at this point, or you don’t. But with figuration the potential for embarrassing hokiness is always there, and I like that danger. It’s harder to pull off a figurative painting, because half the time it can be so wrong. I like to fly quite close to that edge. ❚