Roger Winter

I wouldn’t have expected to encounter the paintings of a 90-year-old artist whose work I find excellent and who has long been a resident of my own city but whom I knew absolutely nothing about. A glance at Roger Winter’s bio shows that he exhibited in New York regularly throughout the 1980s but only rarely after that; it seems that since then he has been a more frequent presence on the gallery scenes of Dallas and Santa Fe. I can only hope that his recent show at Tara Downs, “Manhattan Valley,” signals this is changing. A contemporary of Lois Dodd and Alex Katz, Winter is evidently one of their few peers, an artist who likewise splits the difference between formalism and observation in order to ask questions about the very activity of picturing and picture making.

Roger Winter, P.S.93, 2018, oil on canvas, 182.9 × 182.9 centimetres. Courtesy the artist and Tara Downs, New York.

The show’s title refers to a small neighbourhood on New York’s Upper West Side, a low-lying area—a remnant, as Wikipedia informs me, of “the valley created by what was once a minor stream draining from roughly the area of the Harlem Meer into the Hudson River.” But the show’s 11 paintings on canvas and 12 smaller ones on museum board (all made between 2018 and 2024) don’t have much to do with urban topography or, really, anything referring to a specific location. Only one of the works has a title that gives a clue to place, but the clue leads nowhere. P.S.93, 2018, is a severely geometrical composition mainly occupied by a number of rectangular planes of blue and periwinkle—parts of a wall, perfectly parallel to the painting’s surface. In front of it, a black railing, and in front of that, a bench, both of them likewise parallel to the surface, bluntly facing the viewer. Only at the left edge, as though to lead the eye into or out of the painting, is anything at an angle to the surface. The railing turns a corner, and you glimpse the end of a second bench in front of it. Those, and a single yellow line across the right side of the ground plane, otherwise an almost blank expanse of grey, are the primary clues to perspective in this very linear composition.

As for the painting’s title, well, there is no P.S.93 in the Upper West Side, or anywhere in Manhattan. Whether (despite the exhibition title) this is a view of the school of that name in Brooklyn, or whether the whole picture is a plausible fiction and the name has been chosen at random, finally seems irrelevant. All that matters is the clarity of tone that pervades the painting, the classical balance that undergirds it, and perhaps most of all the subtly variegated touch with which this deceptively straightforward but ultimately mysterious image has been rendered: the gently rhythmic inflections of facture that give the work its lasting fascination and that bind form and image so tightly together.

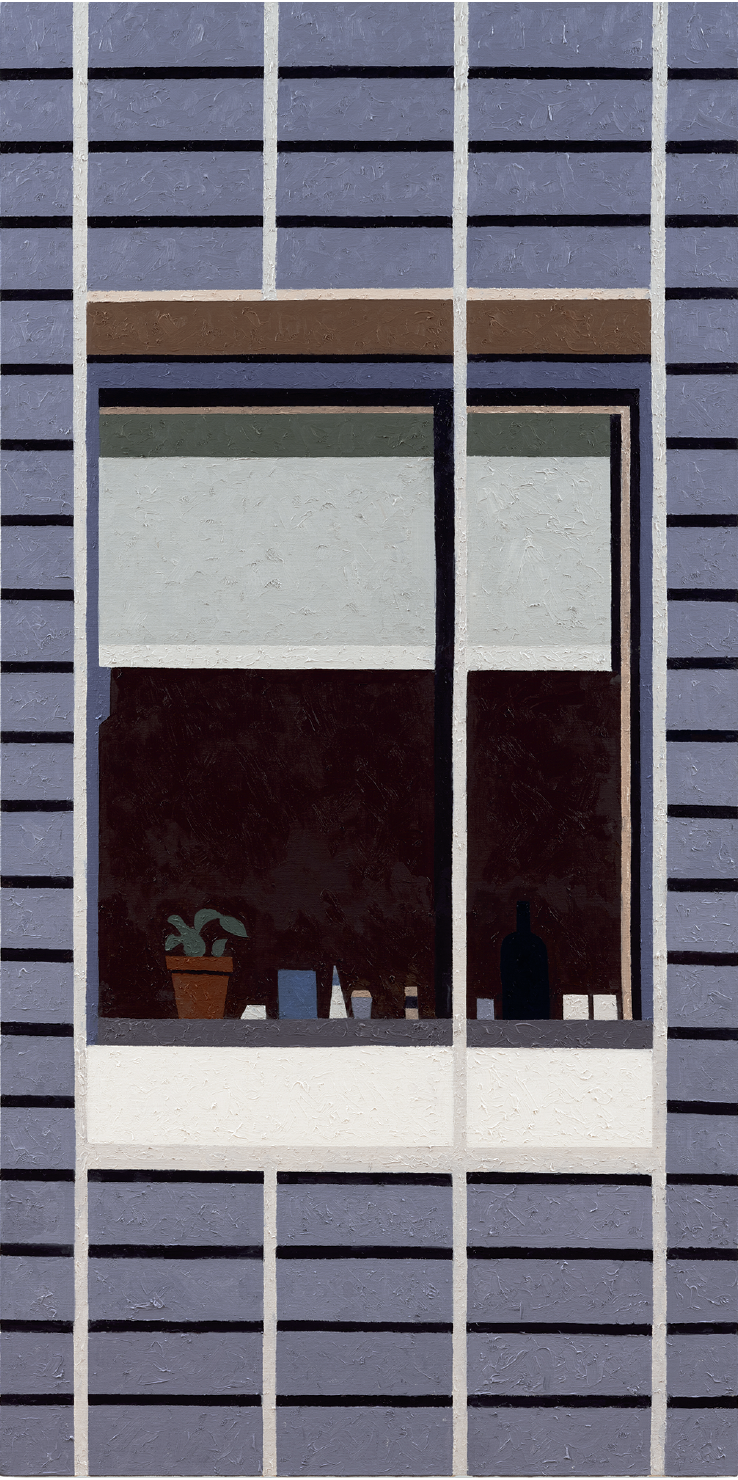

Roger Winter, Window with knick knacks, 2024, oil on linen, 152.4 × 76.2 centimetres. Courtesy the artist and Tara Downs, New York.

None of the show’s paintings has a figure in it, but in a strange way, some of them do have what I can’t help seeing as something like substitutes for the figure: windows. As in another painter’s work we might study a face in hope of some revelation (which is possibly not forthcoming), in Winter’s paintings windows may be the only things we can hope to look into as well as look at. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, then windows are the eyes of architecture. Window with knick knacks, 2024, teases us with the possibility of some narrative disclosure—won’t the potted plant, black Morandi-esque bottle and other less identifiable objects on the windowsill tell us something about whoever inhabits the unseen interior? The opaque brown murk around them ensures that the interior must remain as enigmatic as the sun-washed outside wall. And then it’s only on second thought that you begin to wonder about the vertical line that, about two-thirds of the way across the window, divides the whole painting from top to bottom, parallel to similar lines on either edge of the window and to ones that touch the window at top and bottom but don’t cross it. When that happens it begins to seem that this must be two overlapping views of the window, perhaps seen at different times (with different objects arrayed on the sill), as if they were collaged together. Again, a seemingly straightforward view of some ordinary sight, bluntly rendered, begins to suggest its own fictionality—this time thanks to an internal dislocation rather than through its title.

Looking online to get a sense of what led to these beautifully distilled essays on picture construction and its enigmas, I realize that, unsurprisingly, Winter’s art has gone through many distinct phases, some of them very different—relying, for instance, in some cases, on intricate detail of a sort that would be entirely alien to the paintings in “Manhattan Valley.” Sometimes it takes a winding path to find a straight line. ❚

“Roger Winter: Manhattan Valley” was on exhibition at Tara Downs, New York, from October 10, 2024, to November 9, 2024.

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition “Jeff Wall” at Glenstone Museum, 2021. His new collections of poetry are Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022) and Water from Another Source (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2023).