Rodney Graham

If asked to name a Rodney Graham work, many would come up with Vexation Island, the 1997 looped film in which the artist—in the guise of a Robinson Crusoe figure—is knocked unconscious by the fall of a coconut that he shakes from its tree. No matter, he soon comes round, only to make the same mistake again. At first it seems odd, then, that it isn’t in either of the two shows that recently gave British audiences a wide overview of the Vancouver artist’s work. Instead, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, featured five other films and 14 of Graham’s signature large lightboxes in which he appears in various guises; and Canada House Gallery in London provided a sample of sculpture, painting and photographic work as well as more lightboxes.

However, Vexation Island’s characteristics of wittily playing with identity, circularity and the logic of media (it’s the ultimate loop) recur throughout both exhibitions. If “Canadian Impressionist” (the London show) sounds like the artist pretending to be other people, then “It’s Not Me” (in Gateshead) might suggest that the pretence is denied: these really are other artists. Yet, not only do both shows come back to Graham, often as the photographed subject (so that it is him far more literally than in most artists’ work), the dissimulation can hardly disguise that it’s very characteristically him—pretences to the contrary included.

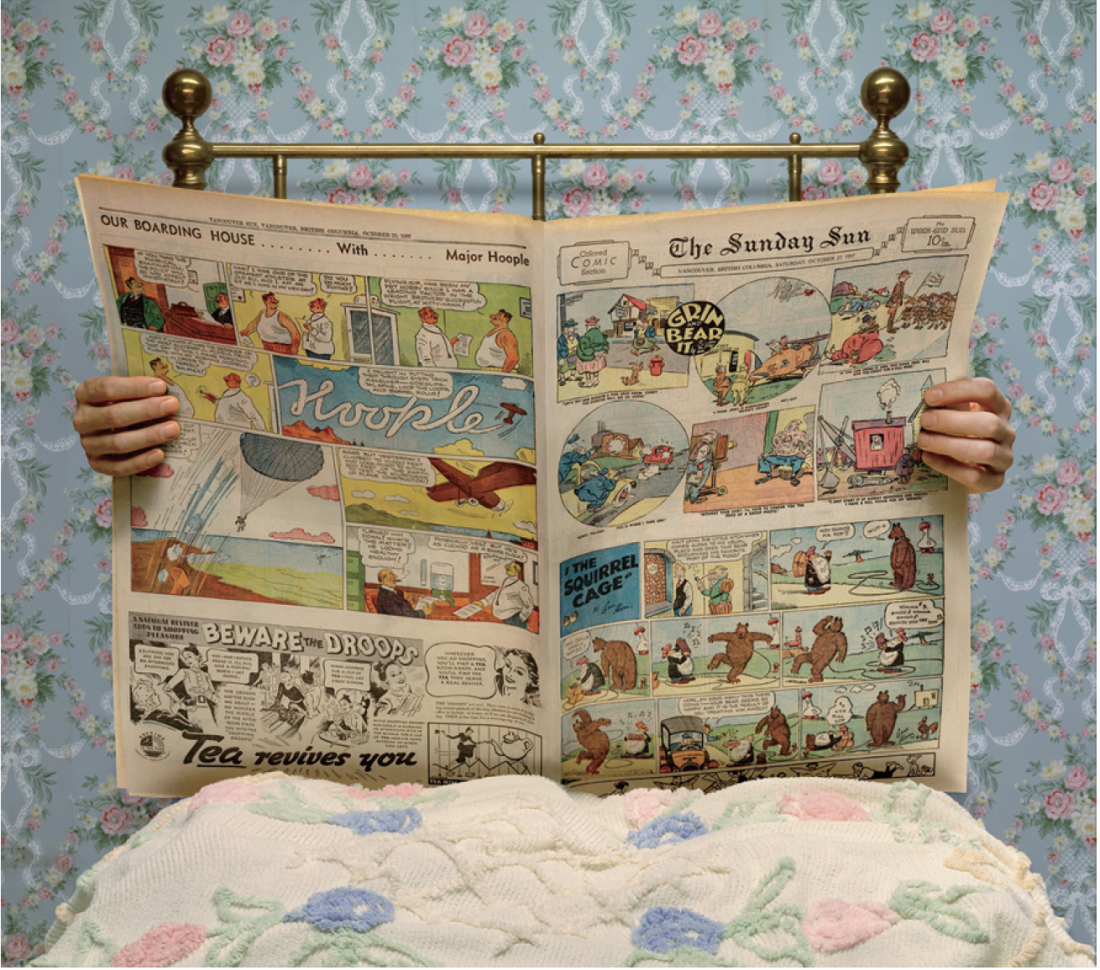

Rodney Graham, Sunday Sun, 1937, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Rodney Graham.

The BALTIC’s floor of moving images works starts with Graham’s first appearance in his own work: to produce Halcion Sleep, 1994, he took enough of the eponymous sedative to be “out of it” as he travelled in the back of a taxi, leaving us to wonder what he was seeing in the dreams that the drug’s name suggests would be utopian. The other—all silent—films emphasize how they are made and shown. For example, the celestial implosions of Coruscating Cinnamon Granules, 1996, are actually, as the title states, bits of cinnamon burned on top of Graham’s stove, and are shown in a specially constructed cinema the size of his kitchen. Rheinmetal/Victoria 8, 2003, elevates and mourns another old technology by showing a 1930s German typewriter slowly covered by sifting, falling flour in the guise of silencing snow, all at cinematic scale, against the clatter of the huge projector.

One of the ways in which it “isn’t him” is Graham’s conceding control of his final images to the production team and photographer he works with, as in the big lightboxes composed with the care of history paintings to contrast with the slapstick tendencies in their content. Graham appears in various guises. In Lighthouse Keeper with Lighthouse Model, 1955, 2010, he plays a lighthouse keeper, in a lighthouse, reading a book about lighthouses, with the evidence of his hobby— constructing scale models of lighthouses— behind him. Everything leads to the lighthouse, so much so that we might read the lightbox as another one. Then, the whole reads as an obsessive exercise in living, which might be a parallel for the artistic path. The Gifted Amateur, Nov 10th, 1962, 2007, represents the opposite sort of artist more directly: Graham plays a man in pyjamas in a room lovingly detailed as belonging to the peak Playboy / Mad Men era of the early 1960s (even the newspapers spread on the floor are an exact tribute, reprinted to look as if new). The amateur is making poured abstracts, which could be inspired by Morris Louis, or could be Graham sneaking in a spoof from his 21st-century position—a reading complicated by the fact that Graham has shown such works as his own paintings. “That’s about a guy who has a mid-life crisis and discovers painting,” says Graham, inviting us to wonder why he himself started using the medium.

That channelling between “professional” and “amateur” also applies to Graham’s music: “a hobby I work hard at,” he says. The melancholically tinged country-rock-folkpsychedelia of the Rodney Graham Band may, perhaps, carry some of Graham’s regret that it’s not possible to be taken equally seriously in both art and music, casting his songs in the role of Rolling Stone Ronnie Wood’s paintings. The BALTIC cued us to this aspect through a concert performance and a slide sequence (Aberdeen, 2000) from Graham’s visit to Kurt Cobain’s hometown.

Smoke Break 2 (Drywaller), 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Rodney Graham.

In Smoke Break 2 (Drywaller), 2012, Graham plays a plasterer taking a cigarette break while standing on the metal stilts used to reach the upper part of walls. Here, Graham shows us what the plasterer may not have seen: how his half-finished wall resembles an abstract painting. The artist, implies Graham, needs the equivalent of stilts to reach the expressive heights. If only it were that simple to hit the nail on the head.

The centrepiece of the exhibition “Canadian Impressionist” addresses exactly that phrase. Assisted Readymade, 2006, recalls Duchamp both by title and by the stool—the same type as supports Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel—on which a hammer is frozen at the moment of attempting to yank out a nail. The seat is covered with paint splatter, which suggests that the retinal ambitions of art that Duchamp sought to dismantle have found their way back, and aren’t so easy to remove. Canada House also has two of Graham’s Cylindochromatic Abstraction Constructions from 2015, paintings that are each formed by eight three-dimensional coloured dots. They economically invoke a slew of art references: Seurat’s post-impressionist theories, Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dots, the effects of Op Art, and Damien Hirst’s use of spots as an end point for geometric abstraction.

Graham, then, inhabits characters and production styles and technologies at will, and all with the deadpan self-effacement typical of many stand-up comedians. Indeed, one means of linking the two show titles is to consider the British comedian and impressionist Mike Yarwood, who always finished his 1980s TV shows in his own voice, declaring “and this is me.” That wasn’t really true, because it was the impressions of others that made Yarwood who he was—and that same paradox applies to Graham. Not being him is the essence of being Rodney Graham—an essence consistent with the apparently evasive tactic of omitting his most famous work. ❚

“That’s Not Me” was exhibited at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, from March 17 to June 11, 2017. “Canadian Impressionist” was exhibited at Canada House Gallery, London, UK, from March 10 to May 27, 2017.

Paul Carey-Kent is a freelance art critic in Southampton, England, whose writings can be found at <paulsartworld. blogspot.com>.