Resonant Surgeries: The Collaged World of Wangechi Mutu

In 2001, after graduating from the MFA program at Yale, Wangechi Mutu began a series of mixed media, ink and collage on paper works called the “Pin-ups.” The women in this series were dressed in fanciful costumes, when they were dressed at all, and they were simultaneously alluring and gruesome. Their nakedness was mediated by the fact that all of them were missing limbs, their arms and legs bloody stumps that rested on wooden crutches or peg-legs. The “Pin-ups” were poster figures for the war in Sierra Leone, victims of a combination of greed and land mines connected to the diamond trade in that African country. They were the initial group of strange hybrids created by Mutu to address a complex set of issues that included African politics, gender and sexuality. Over the next two years, she made more series that constructed human and animal figures from images cut out of the pages of fashion, travel and porn magazines. Her ability to insinuate meanings that are political, aesthetic and psychological, without ever declaring what the images are really about, is unique. They are like warnings of medical and cultural problems to come. She employed the collage as a premonition, the drawing as a threat.

Histology of the Different Classed of Uterine Tumors, 2006. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkens & Co., New York

Wangechi Mutu was born in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1972. After attending the International Baccalaureate program at United World College in Wales, she came to New York in the mid-’90s to study art and anthropology at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art before focusing on sculpture in the graduate program at Yale. Her collages, videos and installations are irresistibly intelligent and seductive, and they are equally repellent. The collages are especially effective in combining a sense of the beautiful and the grotesque–her mottled and patterned surfaces are as exquisite as animal pelts and as disturbing as disease-ridden skin. She has an uncanny sense of gesture, so that her figures organize themselves gracefully in space but walk on chicken feet with the aid of mechanical limbs. In a collage called A Passing Thought Such Frightening Ape, 2003, a golden speckled woman/creature with an exotic face–heavy-lidded eyes and a full mouth–promenades with a deranged-looking primate, whose crotch remains covered by a discreet bit of foliage. Butterflies hover in the air above them and, for all intents and purposes, they look like a bizarre reimagining of the Edenic story: Ape Adam and Eve Talonfoot about to saunter out of Paradise. In another collage from the same year, The Bourgeois is Banging on My Head, a human/tree hybrid pushes a sharp blade into the forehead of a birdlike woman, her arms replaced by feathered epaulettes that curl over her shoulders. She seems to be in a state of ecstasy and her skin is a patchwork of textured areas that you could read as fungal or fashioned. To complete the picture, a ravenous shrimp-shaped thing with a single high-heeled leg and a ponytail is either about to suckle or consume her left breast. It is a beguiling, horrifying image. Mutu has made collages that picture disease (her Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors, 2005, are especially gruesome and owe an acknowledged debt to Hannah Hoch’s From an Ethnographic Museum), but these creatures, made from pieces cut from fashion and porn mags, are as bizarre and compelling as anything she has ever done. In an artist’s statement, Mutu has referred to “the beauty and survival capabilities of the human imagination.” She could as easily be talking about her own instincts and achievement in a career that is only seven years in the making. In the following interview, she addresses the ambiguous effect of collage, the method of art making she has made her own in that short period of time. “When two ideas come together, it doesn’t always create a logical result, it doesn’t add up to what people expect, and you can’t tell where one begins and where one ends.” She’s right about all the unknowables. But what she hasn’t said is that those uncertainties are producing some of the most remarkable collages of the last 50 years.

The following interview was conducted by telephone from Brooklyn on Thursday, January 17, 2008, the day after the opening of “Collage: The Unmonumental Picture” at the New Museum in New York, which included Wangechi Mutu’s installation, Perhaps the Moon Will Save Us.

Interview

BC: What emerges in your work is that collage is a natural way of recognizing how you view the world. If the world is a broken place, then is collage a way of demonstrating that brokenness or a way of putting it together again?

WM: It’s both. Because in the end, the image has a beauty to it. It’s not something I’m afraid to address and I’m not trying to dissuade conversation. I’m optimistic and I believe we grow and will learn to heal. I guess I’m in this in-between situation, culturally, economically and socially, where I’m not ignorant about how these things relate to one another and the bridges between them. I love collage because I studied sculpture and I’m fascinated by material. The kinds of things I choose in the collage have a very particular resonance for me. So if I pick up a National Geographic or Motorbike magazine, it’s about what it stands for and who reads it and why. What is its purpose and how are women’s bodies used in there? As a woman of colour, how I’m represented in these publications is of absolute relevance and importance to me because it tells me where I stand in that particular culture. So, in that way, collage tells us not just what cultures have produced but what they’ve fostered. You can tell what American mainstream culture is thinking by looking at a newsstand. For the most part, there’s a lot of misogynistic material, and a few things that have to do with sports and cars. If you want to know what an animal’s system is about, you look at its shit, like elephant dung. If you want to know where the animal has been and whether it’s healthy, you sift through its stool. That’s a little bit what it’s like when I look at media; it’s quickly processed, it’s not the most high-end knowledge but it definitely gives you a cross-section of what is going on.

What was evident from the beginning is that you have a strong sense of how the body articulates itself in space. As a viewer, you can recognize the original gesture even though it’s been played with and distorted.

Drawing the body is one of my favourite things. It’s always been interesting to me, even before I was quite sure how I wanted to work and what I was going to end up doing with my life. I was always drawing and doodling gestures and it built in an innate understanding of the body. For example, in dance, the body has the ability to describe and be a language in and of itself, so pain or surprise or dependence can be described using just the figure. That’s something I’ve done for so long that it comes quite naturally to me and now I’m able to put it to much more pointed ends in deciding how I want an image to communicate. I do mine a lot of gestures from the fashion world, gestures that are used to pose models in contrived ways. They sell fashion really well, but they’re the most uncomfortable things you can possibly ask a body to do.

Forensic Forms, 2004. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

When were you first attracted to collage as a medium?

I made some collages for my application to undergraduate school. I remember I put a number of collage works in the home test but I didn’t really know much about it then. The reason I ended up coming back to collage in the last seven years is that there was more available material and it allowed me to create narrative work but with a non-realistic element to it. I was messing around with perspective. I’d seen a few works by Picasso and I loved the way he looked at things from different angles and they still ended up in one picture plane. I really embraced the medium when I started making collage figures of the female body in the “Pin-up” series. At Yale I had used collage as a thinking ground, as a place to sketch. When I was creating a performance, I would make these little cut-out pairs. Sometimes it was as literal as a body and a head from somewhere else and I’d splice them together.

So there would only be one move?

One move, two pieces, like a snake with a woman’s leg or a machine attached to a fishtail. I loved making those works because they disturbed the notion of binary being simple. So instead of doing black and white, red and blue, or big and small, I was trying to complicate that issue. Partly I was thinking in terms of two histories; I was moving from seeing myself as a person from Kenya in America, to seeing myself as a fusion of the two. When two ideas come together, it doesn’t always create a very logical result, it doesn’t add up to what people expect, and you can’t tell where one begins and where one ends. I was playing with that idea without fully understanding how to break out of it. I was just enjoying these little pairings, almost as if the process were an exercise in self-portraiture. But they were good because they forced me to come up with unpredictable results.

Were you after a sense of disruption or did you want some kind of harmonic relationship between the two cultures?

Honestly, it was both. The pairs had a beautiful cohesion and they worked together formally. A shape would end up looking like a perfect teardrop but it was made from two incredibly different sources, one photo and one cartoon. It wasn’t even about Kenyan versus American. You could see it from so many different perspectives, like a child’s mind versus an adult’s. My adult mind was maturing in a whole different culture from where I had been raised. So it was cohesion in the sense that I wanted them to live together and be bound into one form, but there was always this obvious sense that those two things don’t belong together. My boyfriend at the time was into graphic novels so there were all these cyborg females with machine bodies onto which I would attach a head. There was one where I had this beautiful ringlet asparagus head. You couldn’t really say, “Oh, that’s a critique on race and different textures of hair.” It was more about formal and psychological exercises. It’s like two instruments that don’t normally sound well together. If you have synthesizers and digital music versus violins and conga drums, you can put them together and there are moments when they sound like they were absolutely built to be together and there are ways that you can make them seem incredibly incongruous.

When I looked at the robotic appendages and animatronic arms, I thought of Francis Picabia, not knowing that you had a boyfriend who was into graphic novels.

That’s good because it means that you’re able to decipher meaning which doesn’t have to be prescribed. You don’t have to know everything that’s going on in my mind to enjoy the work.

How does a collage develop? Do you have a central idea or figure out of which you want to generate the overall assembly of the image? Is the process one that starts with a very firm sense of where it will end and then accidents and serendipities begin to happen?

It’s both. Now I have a greater sense of confidence and I can comfortably say I want to head in this direction, I want this to be a powerful leaping figure and I want this colour. But it happens in tiers. I start off with an 8.5 by 11 sheet of paper, and then I transpose that image to life-size, a scale I’m using more often now. Then I start to shift what happened in the original drawing. Maybe that life-size looks a little too literal, so I slowly augment things; perhaps something looks too natural, or it’s too elegant. So I disrupt it, I remove a limb or change the elbow. When I’m doing that larger drawing, I temporarily place all the elements that are not going to be inked and I add the mechanical elements, like the beak on the face. Finally, I put on the Mylar and start to ink. I can see the drawing from under because Mylar is translucent but, when I ink, I’m very aware that it does what I want it to do. It will get to a certain point and then the meniscus of the liquid breaks. It trickles away here and there and creates a new form, everything from a drip to a bulge.

Or the kind of pooling that results in that mottled effect so many of your works have?

That happens within the lines that I want the drawing to be in. But if it pools beyond a certain point, it creates a river and sometimes you don’t know where it will go. It might go from the belly down to the knee and if you leave the work for five hours, when you come back, you realize the knee has turned into two legs or something.

So these things grow on their own?

They do and that is now a big part of the work. Most of the work in my show, “Yo•n•I,” at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London this year was overpoured so that it could become what it wanted to be in the end. I call it “determining.” I allow the chemical and natural qualities of the material to decide how it wants to lay on the paper. For example, in A dragon kiss always ends in ashes, the figure was almost perfectly placed on the paper and when I came back, her face had opened up. So this dragon or serpent that she’s kissing actually created itself overnight. That kind of thing is important because being an artist wouldn’t be interesting if I knew everything. I’m intuiting some of the stuff I’m working on, absorbing from the culture, and I haven’t processed it. So I’m far more likely to be honest and unedited. If I know everything about the result, I might as well be doing graphic design. Also, you can get really good at your own thing and you start making work that bores you, and when you’re bored with your work, then people get bored with it too. So I try to keep this element of surprise. I don’t know and understand everything, even things that I care about, so I want to know what this process can teach me about life, about the work and about myself. That happens by taking these risks. If there’s no risk, then there’s little surprise and little to be gained from a situation. Also, because I can be a little obsessive-compulsive, it’s fascinating for me to find ways to loosen up as opposed to find ways to become more detailed and more intricate.

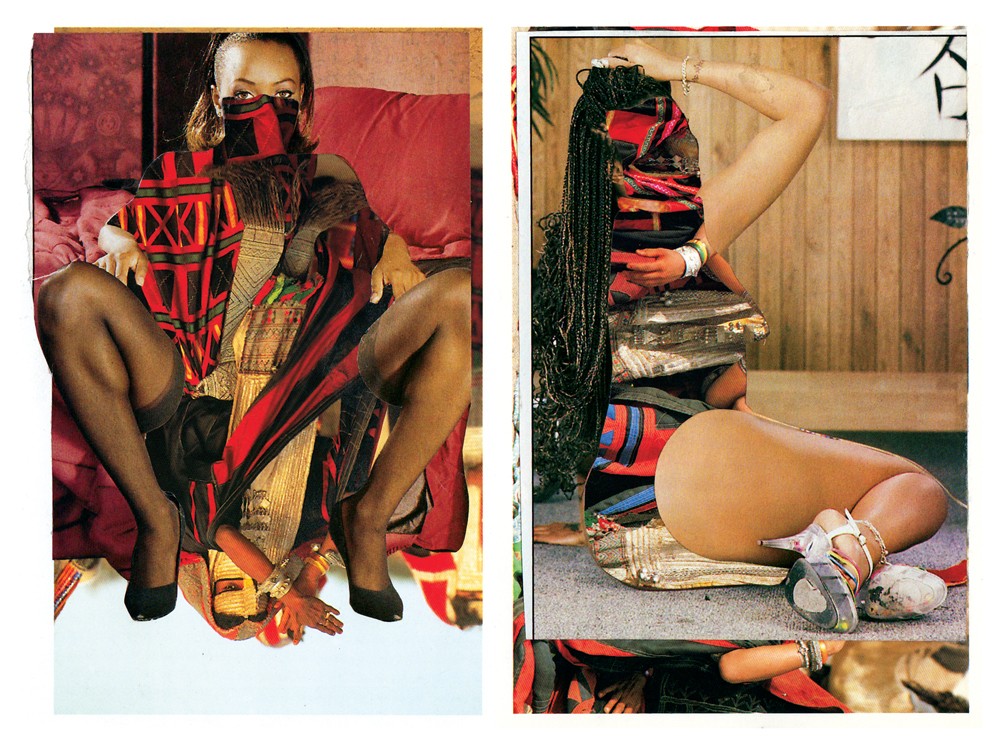

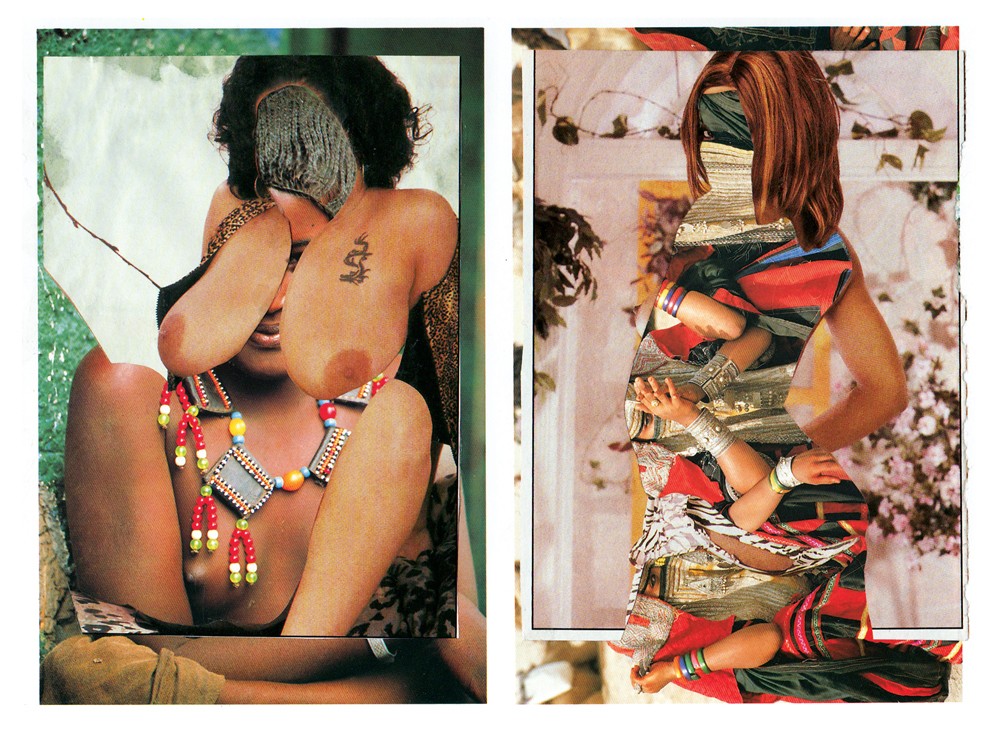

You have one collage where you use Kora dancers. You simply place a painted face with one eye upside down and the divided face becomes a kind of corset. The woman’s hand resting on her butt covers the other eye and you don’t see the whole face, and then the hair on the upside down-dancer is like a ruffled pair of panties. It’s a simple combination but it has a lot of legs in the composition. Do you like the idea of simplified moves that carry a lot of weight and meaning?

Yes. You see that sort of thing in jazz. There are so many things that seem incredibly simple. It’s like one line but the amount of space it occupies and the number of references and illusions it brings up are infinite because the gesture is so well placed. The “Ark Collection” used photographs from the Women of the African Ark book and that particular piece still seems really simple. Because I make collage almost on a daily basis, I had hundreds of these cut-outs. I was playing with them, moving them around, finding a way to create an eye out of another figure or finding a way to push this figure’s back further out because of the curve of the necklace in the other image. They seem like they’re in perfect conversation but they’re from really different universes and they’re intended for very different viewers. But to me they have the same inherent problems, so I wanted that simplicity to point out that they’re actually using the same tools. They’re forcing a fiction upon the bodies of these women, which people either accept as true, or they go, “Wait a minute, why is this woman in her muslin bouey-bouey next to this bent-over, highly sexual figure?”

The Ark Collection, 2006. Courtesy Sikkema Jones & Co., New York

In Ark Collection 3, you see a woman bent over. I assume the image source is a porn shot but inside her body are the arms of a smiling cluster of figures. What’s interesting is that, as a viewer, you understand the sexual gesture of one image and then you’re wonderfully confused about what the body contains.

Exactly. Because it’s flat, it almost seems to be about flatness but it isn’t. It’s about multi-dimensional and multi-perspectival discussions on things like women’s sexuality, imaging the woman, woman’s ability to control how her image is being portrayed, how should she be viewed and who really is in charge. It’s all those arguments that in their own world are understood as a norm. I’m trying to say that they’re not a norm because of all these other things that are happening. I’m cutting into them to find the truth, to find the humour, to find the sickness. In a way, they’re like little surgeries.

There are women artists—I’m thinking of Marlene Dumas and Cecily Brown—who seem to be using sexuality in a different way. In some sense there’s a reclamation of the gaze.

I think that feminism in the arts has done a considerable amount of work and is allowing for a multi-faceted discussion of the female body. I don’t know where I’m placed, but I do know that there is an engagement now and people are receptive to work that has a sensual nature but that is at the same time critical of the dehumanization or the objectification of female bodies in magazines and in public imagery. You can actually create an erotic and sensual image from the perspective of a woman and, at the same time, be very clear about how that line goes from a sensual and self-empowered argument to something that is made purely for the male gaze, or for selling magazines or objects or cars. But I don’t know if I can say that I belong with this particular argument. Nor do I want to. Part of my baggage with feminism is that it still hasn’t taken into consideration the work done by women outside America and Europe. We’re coming from very different behavioural patterns as far as how the patriarchy expressed itself on us. European and American women occupy a very different space from African women, and even that is too general because there are different countries with different histories and different religions. In the end, one of the most fortuitous things about where we are in the contemporary sense is that I can speak from a personal perspective and I can speak without necessarily having to carry all of women’s baggage in every single piece of work that I make. I can talk about them from an ambivalent perspective and that’s okay. All the things that men have been able to do in literature and art for centuries are things we’re getting closer to. But I still feel there are many battles to be fought concerning how women are placed in society. This is outside art because most women in the contemporary art scene are privileged, educated, healthy and accepted. They are part of the intellectual circles that they work with and around. But in other spheres you’ll find women who are oppressed in the traditional ways that feminism protested, fought and bled for. And images are images and it’s not the same as health and hunger and mother mortality rates. It’s a very different sphere; one belonging more to the mind and abstraction, and the other to practical, urgent issues. Some artists deal with them, some are activists and work in several of those worlds, but I see the two as unrelated. There is confusion in the art world because of this attempt to be diverse, when we’re actually all quite alike. I went to Yale and someone else went to Columbia and we’re sitting on this panel and we’re not representing the diversity of women and their issues. We’re actually preaching to the choir.

But the history of attractive women in art has been a problematic one. Think of the way the work of Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke was viewed. As artists who used their bodies, they were dismissed because they had the misfortune of being beautiful. You’re an attractive woman and aspects of your work represent a kind of indirect self-portraiture. Have you felt the impact of the weight of beauty? Is your generation free from the problems that Schneemann’s generation faced?

It’s an issue in my case because black women in the arts are still incredibly exotic. There’s not that many of us and there are often times when I walk into a museum to install an exhibition and it takes a while for people to register that I might be the artist. We’re not used to seeing women of colour, especially black women, in powerful positions in the art world. The other element is that beauty is subjective and I have to say that it’s very sensitive ground. I remember when I was at school at Cooper Union, that’s where the grasp I have on contemporary art started. The teachers were rigorous, well-read and brilliant. Their breadth of knowledge was tremendous and the people they brought in to teach and work with us were also incredible. But we would have discussions about art and one of the worst words you could say in class was “beautiful.” I remember thinking, What in heaven’s name is wrong with this word and why do people get a rash every time they hear ‘beauty’ or ‘beautiful’? I went from questioning to resenting why no one was willing to discuss why we couldn’t utter the word. I believe the reason is because beauty was actually available to them, their culture decides for the whole world what is beautiful, how beauty should evolve, where it begins and ends. So they were rebelling against the very thing that had protected them. They didn’t want to use the term “beauty” because they owned it. Maybe “beauty” is a sensitive and politicized word for people who have a hard time describing their own culture at this particular point because of the hierarchy colonization has set for things. It’s not something they want to reject because they’re still fighting to have it. If your entire history of art and your language and your culture are considered to be primitive, maybe you’ll fight for the idea of something being beautiful.

The Ark Collection, 2006. Courtesy Sikkema Jones & Co., New York

You described “Pin-up” series as “distorted glamour Frankensteins” and critics of your work have agreed; Peter Boswell says what you’re doing is “a slinky metamorphosis” and The New Yorker talks about your “creepily seductive aesthetics.” Do you want it both ways: to have the beauty and its opposite at the same time?

I think so because things and ideas exist, at least in my mind, in contrast and in relationship to other things. I also believe that how we process and recognize things is relative; what one person is scared by has little to do with me and more to do with their own history. So I do want to slip back and forth in those places. I also want to draw people into the work. I don’t feel privileged enough to be entirely invisible or too vague.

Do you want to seduce them?

Seduce or awaken. What it is that flowers do when they bring the bee in?

Well, they have pollen. The question would then be, what is the pollen in your work?

I guess it’s the visual yumminess of it. This work, Perhaps the moon will save us, in the New Museum show, “Collage: The Unmonumental Picture,” is supposed to be seen from a distance as an autumn scene where the leaves are falling off the trees. It’s fairy tale or folk tale imagery, but when you get closer you realize they are pigs and they’re hairy. They’re actually dead pigs. I’ve got a lot of animal pelts in the work, all of which are such a big part of how wealthy, fat and overfed this culture is. The piece is very much about that. How do you draw someone in: you have something that is quasi-simple. You can see it in the “postcards” too. There’s a colourfulness and a lovely juxtaposition of pattern, light, shade and line, and your eyes are drawn into it and then slowly, like when you walk into a dim room and you get acquainted with what’s going on, it becomes apparent that there are ghosts in the room, or there’s a disturbance in the room. But unless you’re drawn in, you’re not going to sit down and dialogue with whatever is there. So I’m conscious of trying to get people to look and see. I’m constantly trying to figure out ways to do that, so the thing you’re drawing them in with is also the thing with which you’re planning to sting them. How do you use the same gesture to draw them in that you would use to smack the hand and wake them up?

It’s the velvet punch, is it?

It is the velvet punch and the Venus Flytrap. It’s all those things.

Are the images in the “Ark Collection” actual postcards?

They’re in vitrines but each and every one of them is the size of a postcard. There are particular pages in pornography where the images are about that size. There’s the centrefold and then there are pages where the magazine is divided into four little postcards in which the women are shown in various degrees of undressing. That’s where I got the idea to use them.

Do you buy porn mags yourself?

I’m a bit of a Catholic schoolgirl prude so I actually send friends to buy them for me. Kenya had a massive ban on pornography when I was growing up (we may still have it), and I think that, compounded with the fact that I was in Catholic school, made me a perfect target for a complete fascination with pornography. I’m actually grossed out by it but I’m drawn to pornography for all the obvious reasons I’ve been talking about. There’s a massive industry of exploitation of the female body that is condoned and promoted. At the time we were doing the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center “Greater New York” show, I said to a writer that I use pornography because it’s the one place where the varieties of black- and brown-skinned women that you find in the real world will be represented realistically. In most magazine that have mass appeal, you’ll rarely find black women and if you do, they look like they’re fictional, as do most of the other women. They’re way too skinny, they’re 14 years old or they look like aliens. But rarely will you find the body types, the skin variation and the realistic representation of women who look like me, except in the most degraded form.

You’ve referred to your “Catholic-obsessed mind” and one of the things about Catholicism is that because of the iconography, all issues get focused on the body. I’m wondering if the body was a natural place for you to find everything from celebration to transgression?

Absolutely. If you have been raised Catholic, you know the suffering, the passion and the drama that Catholic imagery is known for. I love it. The things that the saints would do and the way it’s written about is vulgar. The saints and the martyrs would be flayed and cut up, people would suck pus out of wounds and they’d end up in heaven. Catholicism is the most pagan religion because it has absorbed and retained all the religions that it’s conquered. In a way it’s this monster—lush, overabundant with imagery—and its dramatizations extend the body to the limit. Christ and the crucifixion is a perfect example of that, as are the gestures on the Stations of the Cross. How does gesture evoke, enlighten and open up the spirit and the mind to imagine these higher realms that transcend our own bodies? Besides all those images in Catholic schoolbooks, we had to look at a Virgin Mary in every single room in the entire school. Mary is invariably beautiful, pious and humble. Her eyes are turned down and she’s always posed as a pure woman. But she never looked like us. She was so delicately well done. I mean, there’s a lily-esque aspect to her veil and it’s incredibly sensual in the most nuanced way. Then there’s this element of her virginity, which is fine when you’re a young girl but then you get to the point where you ask, “How in heaven’s name did this woman remain a virgin?” I think all those contradictions were fundamental and important to my development. They’ve added great amounts of humour and madness to understanding how female sexuality is used and abused. So all those things are incredibly informative for my work. My parents were actually Protestant and their church is pretty boring. You were worshipping idols, an object. I love that Catholicism envelops the culture into which it is placed, or into which it forced itself. One of the things about the Catholic Mass is that we were encouraged to use Kenyan songs and we were allowed to add traditional instruments. Mass was amazing, it was so upbeat, with all these different instruments and lots of drums. Even though it was guarded, there was all this African dance. It was interesting to see how much space there was in Catholicism for alteration and translation. As long as it remained Catholic, you could say the Mass in any language and you could wear traditional garb. We can talk about splicing and what that means and how placing together two different histories of knowledge was something I knew was possible because of the Mass. Syncretism is incredibly interesting to me, so I’m fascinated by Haitian voodoo existing underneath the veil of Catholic icons. Candomblé and all those religions have used Catholic saints, not just because they’re interesting but to protect themselves against the colonizing of the Catholic church so that they wouldn’t be fully eliminated. It’s also an interesting kind of masking that I’ve used in my work as well.

Buck Nose, 2007. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

How much of the message of the work is dependent upon a knowledge of the sources you’re using? You use hyenas in the “Creature Series” and “hyena” is an especially derogatory slang term for female in Swahili. Is it necessary to know that to understand the piece?

I compare it to appreciating music in a language you don’t understand. If you really want to appreciate it more, you can look for a translation. People will listen to Hugh Masekela for years and have no idea what is being sung. But the nature of the voice, and the complexity and the nuance with which the music is played, all those things are more appealing than understanding the intricate language. You can appreciate Mozart without understanding the whole history of German music. But it can help to know the mythology of a particular animal. I don’t necessarily think that all Kenyans would look at my work and say, “That’s what she’s saying.” But there is obviously a jarring aspect to seeing a well-posed female figure with this scraggly hyena mask. I think that’s the way masks operate in general. Think of the Guerrilla Girls.

Thelma Golden makes a fascinating observation about you. She says that you are “subtly but forcibly trying to redefine the nature and understanding of African art.” That’s a pretty heavy mantle to drop on someone’s shoulders. Is part of your discourse an attempt to change the perception of the art coming out of Africa and specifically Kenya?

Unfortunately, because there are so few of me here, I end up being responsible for carrying the mantle of things that I never intended. I’m susceptible to it as well. Sometimes I do say this is mine to take on. But circumstances have made it very difficult not to see me as an ambassador of a particular history and a particular place. She’s complimenting me but I think she’s overestimating how much one person is capable of. I’m also coming from a very different tradition. This is not a tradition where I’ve been mentored or schooled or one that has a history that is thousands of years old. So how do I represent the history that is my people when I’m a conglomeration, when I’m a fractured and additive creature from many different worlds and generations? Is Dana Schutz representing contemporary Jewish New York culture? Maybe, but I don’t know. There could be some kind of connection but it’s a tricky one.

It’s even more complicated. It seems to me that if you look at the artists in exhibitions like “Africa Remix” and “African Art Now,” say Camille-Pierre Pambu Bodo from the Democratic Republic, or Joseph-Francis Sumegné, or Barthélémy Taguo, who is from Cameroon, and whose work, incidentally, sometimes looks like yours, then you realize how different they are. Expecting them to be similar would be as wrong-headed as expecting all Canadian west coast Aboriginal art to look the same.

That’s exactly it. I think that the word “contemporary” is my saving grace because it’s where the individual breaks off and where you are allowed to invent something that may have no necessary relationship or loyalty to one history or another. No one lives in a bubble and no one isn’t influenced by everything around them. The material you’re working with has much to do with the time in which you exist. Working with Mylar, which didn’t exist 70 years ago, has allowed me to make collages that look like they’re in-between sci-fi material and something very organic. It happens because Mylar is able to take on both perspectives from both ends of history. We’re completely influenced by where we are, but in the end I don’t feel it’s fair for anyone to have forced upon them something they may not want. Also, how possible is it that I would be carrying the entire history of anything?

I was especially taken by your conversation with Barbara Kruger where you talked about art being a safety zone—“sanctuary” was the word you used—where you could be both vulnerable and inquisitive. Is it still that zone for you?

It is and I say that a lot when I talk about present-day issues, like the political upheaval going on in Kenya. People ask me if I’m involved in other ways and, when they do, I have to out myself. I’m an artist and that’s one of the most privileged positions. I get to talk about these issues but I’m not on the front lines. I can do my work from a safety zone but I can also do it in such a way that it allows me to be different things in the work. I can act out the victimizer or the victim; I can perform the role of the manipulator of the image but also the manipulated. I think art can carry those two positions at the same time, and it can complicate how people see you. I often get confused for my work. That in itself is interesting because it addresses the fact that people are still not used to divorcing a black female face from her imagery. Often the work is not even a black female image; it could be a green face or a purple face.

So is the woman in Riding death in my sleep from 2002 an aspect of self-portraiture? She is white-faced.

In that particular body of work, I intended on having people come up with descriptions for these females that got them into a tangle. So if you start by saying she’s not black, I would say, what’s black? Well, her skin is this colour, and I would say, she could be albino, and they would say, well, her mouth is this size, and I would say, do all black people have that kind of mouth? I’d run into all these non-scientific, ludicrous racial stereotypes. In Kenya, where 99.9% of the people are black, it’s irrelevant to describe anybody that way. You have to be more specific. So coming from that position to America where everything, at any given moment, could be seen from a racial perspective, I wanted to mess with those definitive, illogical and irrational descriptions that have been used to oppress people for so long. A lot of it is centred on the face. If you look at science fiction, you’ll notice that when aliens are described, they don’t use the size of their arms to point out the way in which they’re different. But we use the face to describe something we’re not familiar with, or that we don’t look like. That’s where differences are first defined. All the aliens wear clothing but their faces look part elephant, part mangled cyborg and part us. They actually look like us in that there’s always an orifice, a mouth, and two eye-like things. So these females look like someone you might actually bump into, but what would you say she is and why would you say that?

So is the Medusa-headed woman posed like the Statue of Liberty a self-portrait, as one writer about your work has said?

None of those works are self-portraits. They all come out of magazine images and they’re all altered after they’ve been culled from the magazine. I talked about the Statue of Liberty because of the way she has raised her hand but it’s not that literal. It may still be difficult for people to float in the work and allow it to take them where it should. I think, talking about certain people’s work, you want to ascribe a history, a specificity and a literalness to it, or else you may be susceptible to your own stereotypes and your own exoticizing, which is what I wanted people to do anyway.

You’ve articulated a need for places in your work where you can be complicit. That’s an interesting word.

I don’t think anyone is pure. Kara Walker is a great example of that relationship between being able to criticize and being completely married to the powers that be. As much as you’re aware of your subjugation, you could be in a full-on relationship and romance with it. We all are.

Walker has paid critically for that complicity in many ways.

Absolutely, especially because it’s a racial relationship, which is still very, very charged ground. It’s an area with which I can’t say I’m fully involved. My family is not American and I don’t have that tremendous historical baggage. That’s what I mean when I say “complicit.” In a simplistic manner, you buy Vogue magazine but you also tear it up, vandalize and reconfigure it to suit your needs in creating a new mythology and in disrupting the idealization of the female body that it stands for. But the safety zone is metaphorical. Meaning that you can stretch your imagination and go as far as your psychology can take you, but you can also come back, ignore those discussions and not have to inhabit it. That’s the position of privilege and sanctuary I’m talking about.

Exhuming Gluttony: A Lover’s Requiem, 2006. Courtesy Sikkema Jones & Co., New York.

Where do you want to take the work now? Does the piece at the New Museum indicate a new direction?

It does. Nothing is completely disconnected from what came before it. The “Star Power: Museum as Body Electric” show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver and “Exhuming Gluttony: A Lover’s Requiem” that I did in Salon 94 in New York had a lot of techniques that I’ve actually refined and used in the New Museum show. I’m enjoying my return to three-dimensions and reaching back into installation. Where am I going? I’m definitely interested in environments, in encapsulating whole worlds that the viewer can enter and, for lack of a better word, travel through. One in which they can lose themselves in a place I’ve made. It’s not that I’ve fully succeeded. I’m still working off the wall only but it’s where I’m going now. If you took the ideas of the way the collage functions and turned it into an actual space where this creature or that figure or these plant-like forms could exist, then that’s what I would like to make the space into.

Will video play a role in that? In Cutting and Cleaning Earth, you’ve used video and yourself in performance.

Video will definitely play a role in it. I’ve enjoyed trying to find a way to use my video collage and my site-specific alterations on the wall in one place. There are many elements and sometimes they seem too many, but I like the challenge to make them feel seamlessly, coherently and effortlessly okay with one another. I’m definitely using more video next to some of the collages. I’m also using a lot of scent. Scent is great for me because it unifies the space; the whole area is filled with these little atoms from this one source and the smell is very much what that place is about. So is it rancid wine, or is it the musky, milky smell that I used in Denver? I used fresh milk. That can add to and actually define what a particular idea is about. I’m trying to use the various senses and to reach into my mind to see what makes a place specific, what makes a place feel different from what you’re familiar with. There’s a lot more smell in the work now and a little bit of sound, although nothing too literal.

Do you think your work has an aspect of the grotesque?

I suppose so, but “grotesque” has become so overused. The ugly is back in art. I think the volume goes up and down, depending on what’s happening. Yes, there is an element of the grotesque but what I find gross and disgusting is very different from what other people find gross and disgusting. But that is also what the grotesque is about: about relativity and specificity and titillation. The grotesque is so general that it’s almost like the word “beauty.”

What’s with the mushroom and the fungus thing that has gone on in the work?

Mushrooms are mysterious because they pop up in the forest, the way toadstools emerge in European fairy folktales. Fungus was one of those things that played into my sense of the grotesque but they reference so many different things. They look like little structures or little stools. I remember when I first used a mushroom, I thought it was really phallic but I also thought it looked like a little man in a hat. I remember playing with what that meant. Then it became this notion of creating colonies of mould and mushrooms. I live in a brownstone and attached is this old shed, which was very badly built. So it was always moist and mushrooms were constantly growing there, they would grow four inches high with a nodule on top like a saucer. They were cute. I didn’t try eating them, since they were coming out of this disgusting floor in the shed. But I thought they were almost like a migrant culture that exists in the most decrepit parts of the city, and what emerges are these fascinating people and interactions. They’re also in-between, in that they’re not really plants. In some cases fungus is actually closer to animal because they eat food. They don’t make food, which is one of the big separations between the plant and animal kingdoms. Also the way they reproduce is closer to the most basic and primitive animals, a sort of asexual spooring. I like the idea that they are a little alien family found in the middle of these two massive kingdoms.

Love’s a Witch, Orfeo’s Underworld Coronation for Euridice, 2006. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

A lot of what you do is a way of normalizing the outside. You keep moving things into a position where they’re able to be apprehended and understood. Your whole interest in science seems to be part of an inclination to want to accommodate things to the world rather than make them seem alien.

That’s true. Because I don’t really think anything on this planet, or in the universe, is alien. Everything is coming from the same place. We’re completely a part of this thing that we live on. It’s about making those relationships and, for me at least, making it consistently clear that we are all one. Actually, my show, “Yo•n•I,” was very much about this notion of coming from one idea, one place and thing. If I’m to say where I think the work is going, I may be wrong and say something completely different tomorrow, but I’m trying to come up with more ways to communicate and fewer ways to argue. Less confrontation and more dialogue. I was listening to NPR and someone was saying that one of the problems with the way America has been functioning is that there is such a respect for the idea of freedom of speech, that it’s such an important thing in this country, and what no one really emphasizes is freedom of listening.

It should be built into your constitution, should it, the right to bear arms and to listen?

And to listen. You have to hear what the other person is going to say, which is different from firing away with your opinion and with how upset you are about something. It’s the only way we’re going to figure out how to exist in this world before we completely destroy ourselves. As artists, we really do have to listen. If anything we do is an indication of what culture is going through, if we’re temperature-takers, and if we reflect the beauty and the disease of culture, then we definitely have to function as major listeners.

You did mention at one time you were watching The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. Peter Greenaway has pushed things about as far as anyone can, doing films on intolerable human acts. Were you looking at him as a way of discovering the outer edges of the tolerable?

Maybe that’s where it started shifting for me. I looked at another film, La Grande bouffe, in which there is cannibalism and misogyny. It’s hideous and very French. I was trying to decide on how to make this banquet table for Exhuming Gluttony. I wanted to capture this disturbance, or the moment after the disturbance. This massacre had happened around a big family table, or the kind of table around which the Last Supper would have happened. In a way, the table became a metaphor for us as a human culture getting together, or failing to get together, where we could have had if not a peaceful, at least a fruitful, dialogue. Instead, carnage and waste happen. It’s not blood-strewn, because it’s all wine, but it looks like a massive butcher’s table. So I was trying to get at the psychology behind that. I gave it a very dark and sinister feel. I think it’s possible to switch sides. It’s very easy to be on the wrong side of the weapon. I also don’t think anyone is inherently evil or inherently good. People develop themselves in one direction or another through circumstance and their own personal belief. We have to come to terms with the fact that we’re all very different, so we have to co-exist in a way that will allow us to slowly soften the edges. Those films but they were a way to use the demon inside the film to awaken the demon inside myself so that I could push that into the work. It wasn’t a place where I wanted to stay. I wasn’t thrilled with the feelings that kind of image generated.

You told a writer that your work “was a reclamation of an imagined future.” Is there still in front of you the imagined future towards which your work is moving?

I think so. I’m not always super-conscious about it but sometimes I do try to think of ideas and peoples that have been eliminated and think what that means. But it goes back to what I said before: I don’t have the privilege yet of being that invisible. I mean that in a plural sense, especially in this culture. The notion of a black, invisible person is still misinterpreted. I try to consider my place in making sure these ideas exist and that they’ll be pushed forward into our thinking about each other in the future. Sometimes I think about it in a very stylized sci-fi way; at other times it’s about the survival of a people and how much work it takes, from so many angles, to come through colonization with a distinct idea of how you would like to be defined, as opposed to how others have defined you.