“Relations: Diaspora and Painting”

“What goes by the name of love is banishment, with now and then a postcard from the homeland.” — Samuel Beckett

Viewing an exhibition during a global pandemic seems a hands-on exercise in liminality at the best of times. With the PHI Foundation’s current exhibition, “RELATIONS: Diaspora and Painting,” you are directed through the doors with the usual pandemic procedures for institutions: hand sanitizer, mandatory mask, the maze of arrows demarcating a regulated route through the galleries with movement, exits and entrances strictly enforced. Much of the world currently seems an abstracted pantomime of previously remembered activity: work that doesn’t feel like work, social relationships mitigated by rules meant to keep people at a distance. We are strangers in our own world now, and participate by mimicking the expectations of the past while trying to build an undefined future.

“RELATIONS: Diaspora and Painting,” more specifically, examines painting, identity and how the medium can become informed and revitalized through cultural memory. Curator Cheryl Sim has organized an ambitious exhibition of 53 works by 27 artists from the US, UK and Canada, all of whom are members of different ethnic diasporas. Sim, a second-generation Canadian of East and Southeast Asian background, has drawn on her personal experience to pull together a large exhibition of vital artists with similar concerns but different approaches, which, in her words, “will allow for a polyphonic experience” among different voices. The exhibition is supplemented with a calendar of workshops, performances and video presentations that reinforce this diversity of approach. What binds the exhibition together is painting, and how each artist reflects, embraces or critiques the ramifications of their own cultural history and geographical situation. In each, the syncretic utilization of imagery and the idioms of the medium make a strong assertion of painting’s enduring potential for revitalization.

The exhibition spans generations as well: the appearance of Frank Bowling, Lubaina Himid, Yoko Ono and Barkley L Hendricks sets inflection points as pioneers in this context, and their approaches are varyingly reflected in the works of the younger artists. Frank Bowling and Lubaina Himid in particular present stark counterpoints: Bowling, a British painter of Guyanese descent, scrappily works within a Greenbergian abstract tradition to coax out sensual memory in a wellslathered tumble of paint. Himid, a Tanzanian-born British artist and recipient of the 2017 Turner Prize, utilizes a carefully crafted pictography at times coupled with vernacular imagery that depicts the tools of slavery in subtle, decorative images and motifs that belie the more brutal nature of cultural memory.

Other painters in the show employ similar methodologies in varying degrees, all knit skilfully, with impact, into the language of their respective media. Firelei Báez’s large works on paper greet you at the beginning of the walk through the exhibition. One, Years of holding your tongue, 2018, is a densely rendered pack of morphing forms supporting a palm tree. Crouched hairy legs uncomfortably hold up an anguished mass of tightly wound black hair, winding like a boa constrictor around the tree base. The crouched legs, bowing under a painfully rendered mass, support a palm tree that seems blissfully unaware of the psychic cost of its own existence.

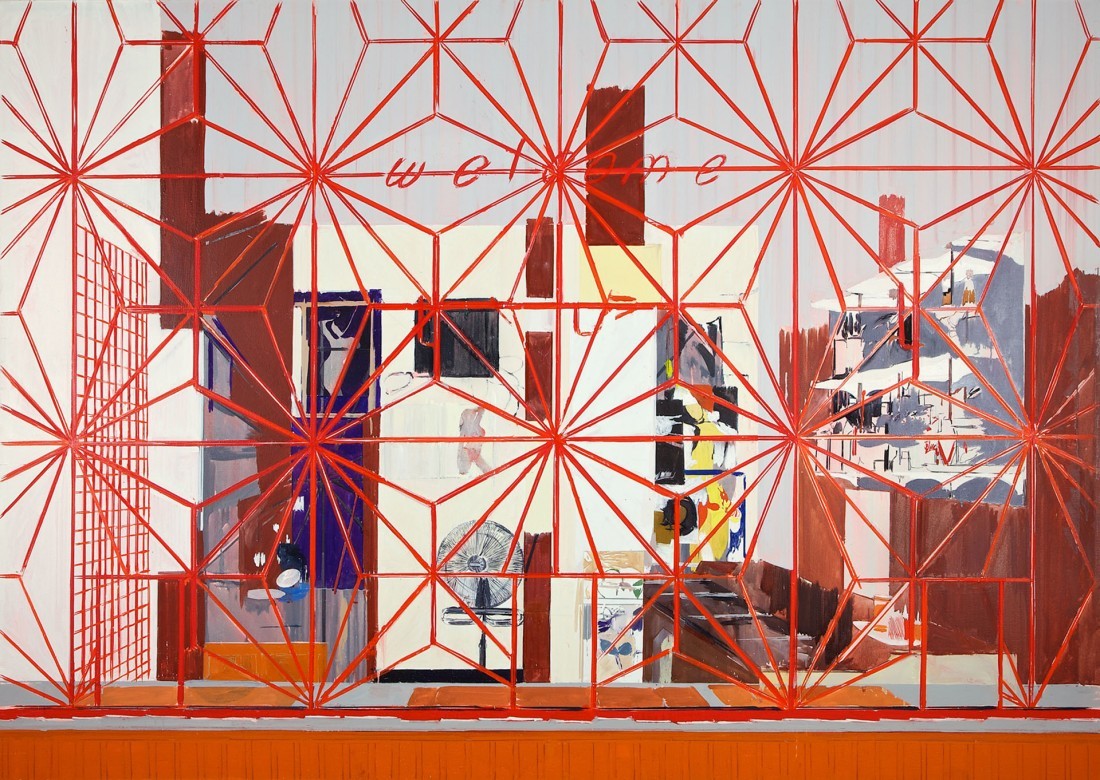

Hurvin Anderson, Welcome: Carib, 2005, oil on canvas, 59 x 83 inches. Photo: Richard Ivey. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.

Landscape is well represented in many of the pieces throughout the exhibition, either as geographically specific memory, political or social critique or a mixture of all of the above. UK painter Hurvin Anderson’s Welcome: Carib, 2005, is a large work where you peer through the red latticework of decorative iron window bars, which are ubiquitous in the Caribbean, a climate that needs no windows. Where living interacts easily between interior and exterior space, window bars are an expedient and decorative security feature. The flat forms of colour behind the grid indicate an interior: an electric fan here, pictures propped up on the ground there, but the ambiguity of the application suggests both.

Other landscapes, like Canadian Hajra Waheed’s small oil on tin pieces in Landscape 1–9, 2019, provide a lusciously rendered drone-like view of a dry-farmed landscape from the Levant.

Montreal-based painter of Haitian heritage Manuel Mathieu, seeming to share a sensibility with Frank Bowling’s work, provides a torn scumble of wet, painterly forms that deftly skirt an anguished anthropomorphism. Imaginary Landscape, 2020, pushes loose, fast paint on the cusp of imagery that seems willing to pick up and crawl outside of the restraints of the picture plane. The artist pins down movements in the paint with a careful corralling, or small, crisp highlighting of shapes, which punctuates points of inexplicable painterly intention. The occasional inclusion of found studio scrap provides the active jetsam for many of his submersive investigations.

Manuel Mathieu, St-Jak3, 2020, Acrylic, charcoal, chalk, tape, fabric, oil sticks, 90 x 75 inches.

On the opposite pole of this varied exhibition, works like the crisp, disturbing works of Sri Lankan-born Rajni Perera utilize Eastern motifs and materials to create monstrously compelling portraits and assemblages. Ancestor 1, 2019, assembles forms and patterns redolent of stiffly decorative Eastern imperial portraiture, with disturbingly articulated multiple eyes, contemporary oversized earrings and faux-gold-leaf background in layers of gold paint.

Strident and confrontational works by Tanzanian-American artist Shanna Strauss cull cultural memory and decorative notational reference in works that compile found-wood assemblages with photo-transfers of influential figures in the artist’s life, bolstering an almost forgotten cultural narrative with decorative motifs and solid, strident forms.

Installation view, “RELATIONS: Diaspora and Painting,” 2020, PHI Foundation. From left to right: Shanna Strauss, Eliza, 2019, courtesy of the artist; Firelei Báez, Ooloi Ciguapa (mass pedigrees of masterpieces unsold), 2018; Firelei Báez, Years of holding your tongue, 2018, courtesy of Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay. Photos courtesy of PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art.

As you exit the last of the two buildings housing the exhibition, Canadian-South Korean artist Jinny Yu provides a finishing point: why does its lock fit my key?, 2018, and Perpetual Guest, 2019. These works display the balance-challenging installation with works on painted aluminum, disturbing the viewer’s horizon with tilted minimal compositions that play from the wall to the floor, and where two delicately raised glass pieces parallel to the floor accompany a vinyl text: “a perpetual guest on the unceded Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe territories.” The disquieting angles of the wall works, the fragile precariousness of the floor pieces make you reluctant to tread too closely. The installation provokes a hesitation in the viewer that echoes in both the exhibition and this historical moment: Can the world be this hard to negotiate? The answer is yes. ❚

“RELATIONS: Diaspora and Painting” was exhibited at the PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art, Montreal, from July 8 to November 29, 2020.

Cameron Skene is a Canadian painter and writer based in Montreal.