Rashaad Newsome

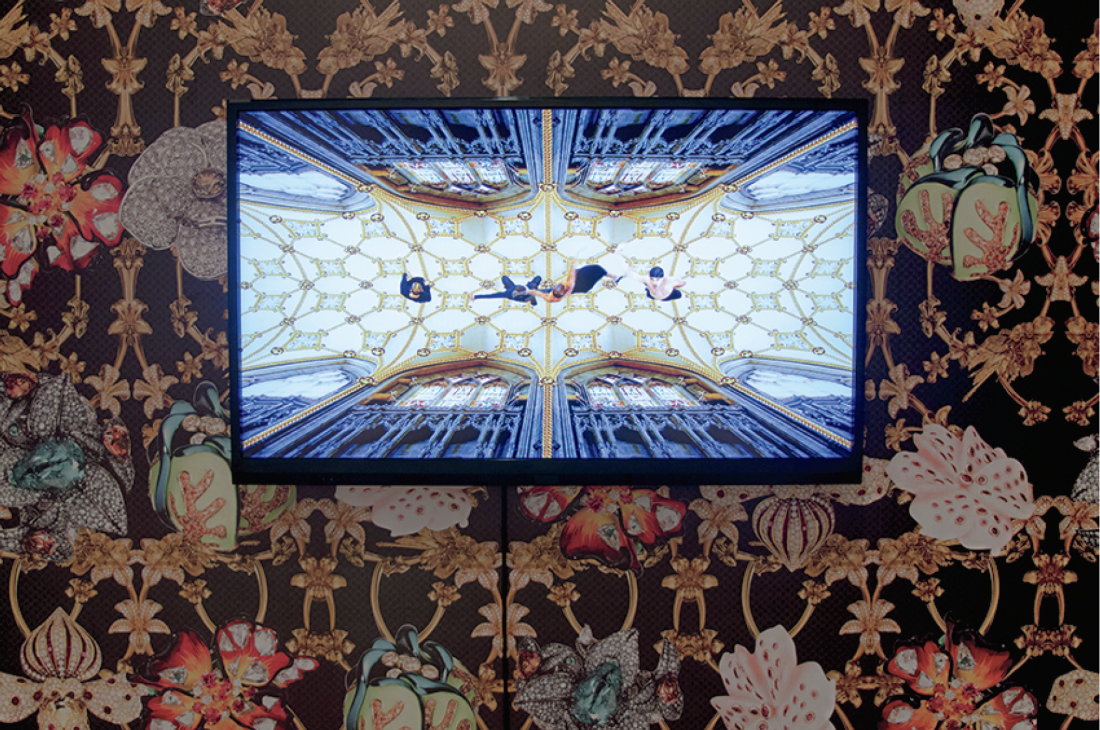

Myriads of break, pole and vogue dancers gyrate, twist and “death drop” (voguing’s definitive move) to house and trap music mashed up with a Hildegard von Bingen medieval chorus. They dance against a psychedelic computer-animated backdrop of intricate mandala designs: abstractions of the ornamental domes and vaulted ceilings of the baroque Lincoln Cathedral in London. Such is the spectacular excess of Rashaad Newsome’s Icon, 2014, a central work for setting the theme and visual tone of “Silence Please, the Show is About to Begin,” the artist’s first Canadian exhibition.

Newsome first gained critical attention when his multimedia performance, Five, was included in the 2010 Whitney Biennial. It stood distinctive for featuring voguing, a dance pantomiming catwalk culture by striking exaggerated models’ poses with rigid arm, leg and body movements. Newsome himself is a prominent vogue ball community member who frequently collaborates artistically with its dancers. This expansive current exhibition, comprising 10 on-site and 2 off-site works ranging from video, audio, live performance, documentation of performance to photo collage, further develops voguing as a dominant theme.

Rashaad Newsome, KNOT, 2015. Photograph: Michael Maranda. Image courtesy Art Gallery of York University, Toronto.

Voguing gained brief commercial London success 25 years ago viatwo hit songs: “Deep in Vogue” by Malcolm McLaren, the Sex Pistols’s producer, and “Vogue” by Madonna. But Newsome is not reviving a retro pop-culture trend; he is reinstating the rich history and core politics of the once underground queer, black dance style of a marginalized community who attended Harlem drag balls in the 1980s. Gender, race and class merged to construct cultural identity through performance by mimicking mainstream fashion. As a fashion-based performance, voguing advances a history of black dandyism as a self-conscious performance style that too often encompassed White-prescribed-on-Black caricatures, notably minstrel shows and blackface. Newsome reclaims Black dandyism as a burlesque of dominant culture.

In this exhibition Newsome expands the vogue dancers’ burlesque of the supermodel to comment on the whole celebrity system through the materials of up-scale luxury goods and commodities—the bling that builds the myth of stardom. In his video installation titled Knot, 2014, for instance, he transforms Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, the artist’s iconic illustration of the ideally proportioned man inscribed in a circle to a trans woman and gay man voguing in the centre of a diamond-encrusted watch face as respective “Vitruvian men.” The ideal celebrityhere has not merely been parodied but replaced.

The video monitor is backed by wallpaper reprinting photographs of jewellery from the collection of Oprah’s W magazine. This opulent imagery was originally designed to cover a Lamborghini Murciélago leading a performative procession forming part of Newsome’s 2013 “King of Arms” exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Rashaad Newsome, Shade Compositions SFMOMA, 2015. Photograph: Cheryl O’Brien. Image courtesy Art Gallery of York University, Toronto.

From Lamborghinis to Oprah’s jewels, ostentatious luxury features prominently in Knot, begging the question of whether Newsome has been too seduced by consumerism to critique it. Monica L Miller, the author of Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity (Duke University Press, 2009), would agree, as she accuses contemporary black dandyism, from the zoot suiters of the late ’40s onward, of marching in the consumer line. Notwithstanding, Newsome clarifies he has not acquiesced to a system that marginalizes his portrayed community, particularly with included collages that link heraldry to bling. Take for example, the heraldic design in LSS (Alex Mugler), 2014, symbolizing the well-known vogue dancer of the eponymous subtitle. Rank is shown in this coat of arms by diamonds, watches, bracelets, a Rolls Royce, wigs and a gold clutch. While this photo collage reflects voguers’ hip-hop-reminiscent fascination with celebrity accessories, constructing heraldry from these status symbols serves at the same time as a public declaration of power from the fringes of prevailing culture. Incidentally, Newsome’s series revives the legacy of General Idea (who have also exhibited at the Art Gallery of York University), artists who likewise explored heraldry to symbolize their identity as queer artists.

Newsome further solidifies his critical position with Shade Compositions SFMOMA, 2012, a performance implying the White dominance of the gay community. The performance comprises a choir of women and queer men of colour “throwing shade,” or sending indirect insults with facial expressions, motions or tone of voice. The chorus enacts a haughty, dramatized version of “throwing shade” with sounds and gestures suggesting irritation—an exaggerated eye roll, for instance. Although the gay community has adopted “throwing shade” as a result of the seminal 1990 documentary on drag balls, Paris is Burning, its roots actually lie in the African-American female vernacular, Shade Compositions. This represents a historical correction of queer culture by highlighting its intersection with gender and race. Consequently, Rashaad Newsome’s liberation of the black dandy permits its serving a political function that ultimately grants the exhibition resonating, raucous and glamourous significance. ❚

“Silence Please, the Show is About to Begin” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of York University, Toronto, from April 8 to June 14, 2015.

Earl Miller is an independent art writer and curator residing in Toronto.