“Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millenium”

Ten painters, ranging in date of birth from Daniel Richter in 1962 to Tschabalala Self in 1990, make up the Whitechapel Gallery’s survey “Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium” works, which, the gallery states, “represent the body in experimental and expressive ways to tell compelling stories and explore vital social concerns.” The show is pitched against the view that “representational painting has been deeply unfashionable and largely superseded by photography and video among young ambitious artists since the critical backlash against neo-expressionism in the 1980s.” That’s very much an institutional assessment: the art market as a whole—galleries, fairs and auctions—has continued to be dominated by painting. Anyway, the gallery’s director, Iwona Blazwick, calls the artists “twenty-first-century expressionists” and suggests they are united by “a political commitment to representing diversity in race and sexuality at a time when identity itself is becoming increasingly fluid.” She also points to “a dark undercurrent” that reminds us of “the fragility of our liberties” and the “entire populations displaced by conflict and climate change.” All 40 works contain figures, only Cecily Brown’s being sufficiently abstracted to cause doubt, so that leaves two obvious questions to be considered: Are the paintings radical, and are they good?

The first question is the easier one. It’s understandable that the Whitechapel wants to claim the cutting edge, but there’s nothing particularly radical here. That’s not so surprising, as painters are inevitably in dialogue with the medium’s history, and these artists tend to embrace their historical influences rather than deconstruct them: the echoes of Guston, Kippenberger, Lassnig, Condo and Doig are evident, and though there are some unusual techniques— Michael Armitage’s use of lubugo bark cloth, Self’s application of textiles—they act as alternative means to fairly mainstream ends.

Tala Madani, Sitting in White, 2008, oil on linen, 40 x 40 cm. ISelf Collection. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

If the work is to be identified as radical, we will have to turn to content. The 10 artists are all familiar from recent London shows, which reduces the likelihood of surprise, but setting that aside, the content isn’t unexpected: it tends to focus on the creative act itself (Cecily Brown, Ryan Mosley, Nicole Eisenman), and political issues, whether public (Armitage, Tala Madani, Richter) or private (self-identity in Self and Christina Quarles). None of which is to say that making paintings about mainstream issues within a broad span of historic continuity necessarily lacks interest. The most startling subject matter remains the earlier work of Dana Schutz— New Legs, 2003, and Man Eating His Chest, 2005, which are violently surreal and emotionally charged. Consistent with that, perhaps, Schutz has run into some difficulties with her subsequent choice of subjects—notably the accusations of racial insensitivity following the display at the 2017 Whitney Biennale of her portrait of Emmett Till.

The German Daniel Richter, the oldest painter here and the only one not based in the US or UK, was taught by Werner Büttner and worked as Albert Oehlen’s assistant. He moved away from abstraction 20 years ago but says that he still can’t establish a style—“I’m just too easily bored”—but he has often transformed found images into something more hysterical and maybe paranoid in colour and tone, and that’s a fair description of what he does here. In so doing Richter pushes further into the trope of “bad painting” than his German forebears: for me, he pushes too far but perhaps that’s a matter of taste. Cecily Brown also transforms found images, typically of famous paintings, but says she can’t make clear figuration work for her. Rather, the figures become vestigial presences in complex compositions that read initially as abstract expressionism with what she herself calls “an aggressive use of space,” at the same time exploiting the naturalness with which oil paint can represent flesh.

Tschabalala Self, Koco at the Bodega, 2017, coloured pencil, photocopies of handcoloured drawings, acrylic, flashe, fabric and painted canvas on canvas, 243.8 x 213.4 cm. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

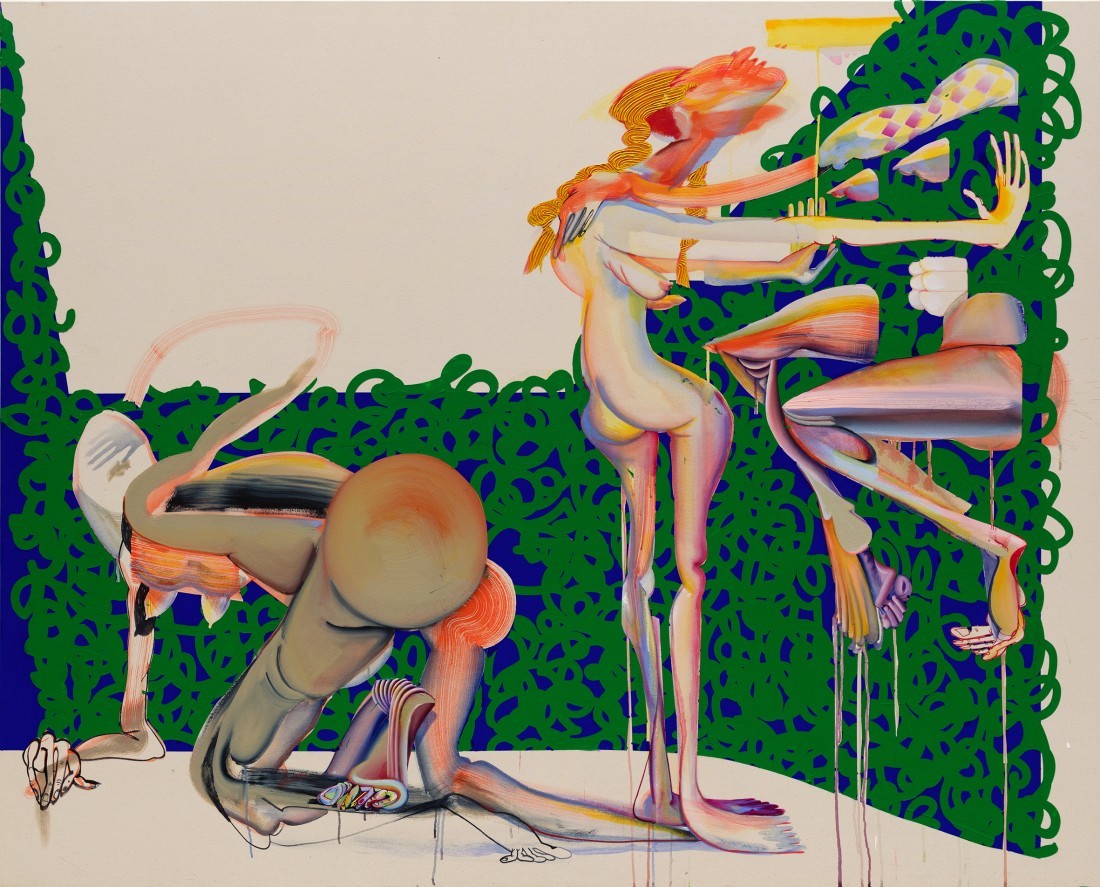

Kenyan-born Michael Armitage depicts scenes that reflect on attitudes towards sexuality and gender in East Africa, giving him a distinctive approach to concerns that are established as a leading current subject. Although he is known for painting on lubugo bark cloth, traditionally used to make burial cloths and ceremonial garments in Uganda, the effect is subtle. Armitage treats the material like a normal canvas, stretching and priming it. This connects the work to East Africa, and its uneven nature means that some parts are difficult to paint on, giving a resistance that Armitage says he likes and that seeps into the look of the work. Tschabalala Self and Christina Quarles are the youngest artists here, and both are current market darlings. They deal with identity from a perspective alternate to those of art historical tradition. Self explores everyday Black experience using collages and recurring print motifs as well as paint, so that the many elements of identity are visibly present. She emphasizes the positive self-construction of identity—for example, through the choices of clothing—in the context of stereotypical representations of Black bodies. Quarles explores female, Black and queer identity in paintings of distorted bodies set against abstracted backgrounds partly derived from computer programs. She describes herself as seeking to capture “the sense of fragmentation that you feel when you look at your own body—it exists as these parts that you’re more or less aware of—and the disadvantage you have of knowing yourself only in fragmentation … it’s about seeing everybody else as these complete, fully formed people”—particularly at moments of intimacy—“and then seeing yourself as a fragmented kind of mess.” I found hard to shake, though, the feeling that these were updates for the present context of approaches more convincingly explored before—in the work of Self, by Wangechi Mutu’s collages of complex identity; and in the work of Quarles, by Maria Lassnig’s depictions of “how the body feels.”

Tala Madani is known for her rapidly gestural, psychologically charged works featuring bald, middle-aged men engaged in crude activities. They are notably entertaining as a critique of men and their behaviour, and retain some of the ambiguity suggested by Madani’s own statement that “as a teenager without any access to porn”— growing up in Iran—“painting was a weird way of turning myself on.” Her recent body of work is “Shit Moms,” which contrasts the messiness of motherhood with the pristine conception of the child by literalizing the idea that a mother could be shit. Madani’s fast and loose way of pushing through metaphors to comical excess and then finding a logic on the other side operates comparably with Dana Schutz’s finding convincing ways to visualize such unlikely acts as self-cannibalism. Schutz’s works from the noughties remain exceptionally fresh, but I was less persuaded by two large recent paintings: Imagine You and Me, 2018, and Suspicious Minds, 2019, which have some mystery and intrigue, but don’t punch you in the gut the way her most memorable work does.

Sanya Kantarovsky shares a use of humour and the theme of parenthood with Madani. He arrived in America from Russia at age 10, and says he thinks of his figures “in relation to the teep, a Russian word which means type, but also … a kind of unsavouriness.” There’s a deliberate negation of identity, he says, in so labelling a character. The exhibition’s primary curator, Lydia Yee, describes Letdown, 2017, as follows: “The mother is hunched and blue with scraped knees and elbows, struggling to bear the weight of her child as she trudges through a lugubrious landscape.” The title has a double meaning, being a technical term for the release of breast milk as well as suggesting disappointment. There’s a compellingly abject quality to both image and manner, consistent with Sanya Kantarovsky’s endorsement of Gusto’s rebuking Ab Ex: “I got tired of all that purity! Painting is impure. It is the adjustment of impurities which forces painting’s continuity.”

Christina Quarles, Casually Cruel, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 196 x 244.3 cm. Tate: Presented by Peter Dubens, 2019. Photo: Damien Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist; Pilar Correas, London; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

At almost 10 metres wide, Nicole Eisenman’s Progress: Real and Imagined, 2006, is the biggest work in the show, an enormously detailed allegorical history painting that contrasts the artist in a studio on a boat, on one side, with an apocalyptic Arctic landscape, on the other, peopled à la Brueghel with figures fishing, hunting, being born, dying.… “I’m like a developer building 12-story high-rise condos on the ruins of art history,” Eisenman has suggested, in this case to baleful effect. Both artist and planet are all at sea. She has a notably malleable style, but the Renaissance seems a more direct influence on her than modern painters. There is also an air of times past in the curiously carnivalesque and theatrical world of Ryan Mosley. He includes two fascinating reworkings of the portrait tradition. Wearing Another’s Head on Your Jacket, 2014, gives equal prominence to two profiles, inspired, says Mosley, by the frustration of viewing portraits in museums, where “you have to look at the back of people’s heads before being able to see the painting.” Duchess of Oils makes a bravura job of putting several faces onto one head—to form a character: that is, “an actor inhabiting multiple characters, making visible the ghosts of previous speeches,” which, he said, could stand for what the 10 voices do in the show as a whole.

Any such selection requires exclusions, and I might note that the “missing figurative influences” could include Hockney, Tuymans and Gerhard Richter; and that plenty of other choices could have been made even within the relatively constrained category of expressive figuration in the UK and USA—for example, Rose Wylie, Dale Lewis, Chantal Joffe, Jim Shaw, Joan Semmel and Katherine Bradford. On balance, though, this is a stimulating— if not especially radical—survey of the fragmented self, equally informed by the history of art and the state of the world.

“Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium” was exhibited at Whitechapel Gallery, London, from February 6 to May 10, 2020. The exhibit is being extended to August 2020.

_Paul Carey-Kent is a freelance art critic in Southampton, England, whose writings can be found at www.pauls artworld.blogspot.com. _