Play Back Playing Forward

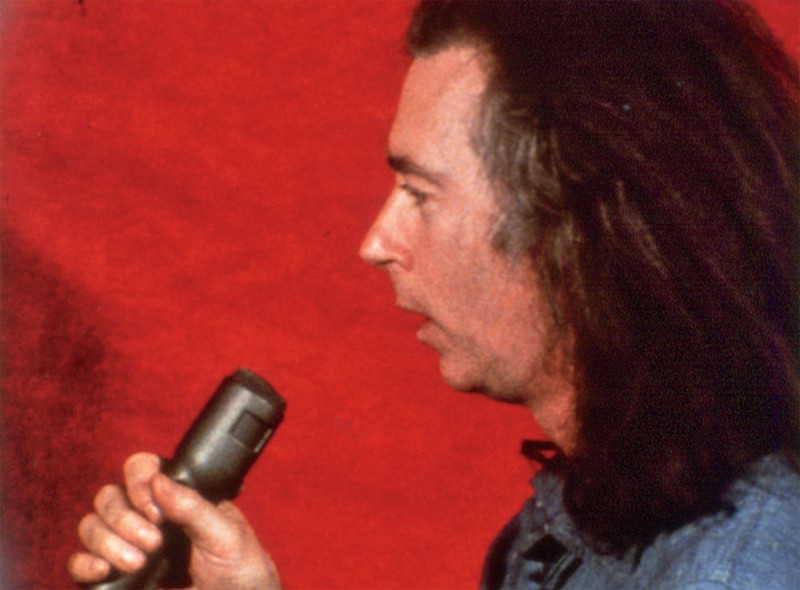

A Conversation with Michael Snow

Michael Snow in Winnipeg at the New Music Festival on Wednesday, January 27, 2016. More here.

How in the world are we to come to terms with Michael Snow’s production and achievement? His migrating categories address a see-sawing taxonomy. “My paintings are done by a filmmaker, sculpture by a musician, films by a painter, music by a filmmaker, paintings by a sculptor, sculpture by a filmmaker, films by a musician, music by a sculptor…Also, many of my paintings have been done by a painter, sculpture by a sculptor, films by a filmmaker, music by a musician.” The fluctuating list is accurate but not helpful in assessing or explaining what he calls his “manifold practice.”

It didn’t take very long for Jonas Mekas, the influential film critic, to conclude that Snow was something special in the New York avant-garde art world. Remembering his reaction after seeing Wavelength in 1967, Mekas compares him to Andy Warhol, claiming that Snow deserves to be the better known of the two. “Any individual piece of art, photograph, film that Snow has made,” Mekas wrote, “is more complex, has more content and contains more aesthetic adventures than most of the things Andy has done.” Mekas was writing in 1995 for Presence and Absence: The Films of Michael Snow 1956–91, but the more time passes, the more supportable that assessment seems to be.

Michael Snow’s diversity is astonishing, measured both in its quantity and quality. He is one of the most significant and influential living artists in the world, and is the most important artist Canada has ever produced. His artistic range encompasses painting, sculpture, film, video, photography, installation, books and music.

The Artists’ Jazz Band, 1973, two ee-1/3 RP< vinyl records, Gallery Editions, front and back of gatefold LP jacket. Photo: Mani Mazinani.

The Artists’ Jazz Band, 1973, two 33-1/3 RP< vinyl records, Gallery Editions, inside left and inside right of gatefold LP jacket. Photo: Mani Mazinani.

The interview in this issue attempts to focus on the place that music and sound have played in Snow’s polymathic diversity. The problem is that focusing on one aspect of his practice is like trying to hold mercury; clutch at its substance and it splits into multiple formations, all of which go off in various directions. When Snow claims early in the interview that he is “a purist” who “doesn’t really make mixed-media work,” he is stating his intention to keep separate all the mediums in which he works. But he is not saying he hasn’t moved from one medium of art to another. While it is true that at various junctures he has focused primarily on one art form—in the ’70s, for example, he left painting behind to work primarily with photography—his imagination remained unruly and apostate. He continued to shuttle back and forth between one discipline and another. As a result, you can trace a painterly sensibility in his photographic expression, and you can see a kind of spatial rhythm playing through the iterations of the Walking Woman as he places her in various urban sites. His fine phrase was that she was employed in “a surrealism of media.” (This observation is included in Michael Snow—Sequences—A History of His Art, an indispensable monograph recently published by Ediciones Polígrafa, Barcelona).

Snow’s original plan in moving from Toronto to New York in 1962 was to leave music behind and to concentrate on developing as a visual artist. But that resolve had some soft edges and while he was making paintings and sculpture, he was also interested in understanding the workings of free improvisation. His studio with its available piano became a listening laboratory for the most progressive music being played in New York. Even when Snow explains what he was doing, his own intentions begin to unravel in the face of a categorical restlessness. In New York Eye and Ear Control he was attempting “to bring together…free improvisation music and a composed moving image,” but then he realizes his wished-for simultaneity won’t hold. “This is a bit more complicated than that,” he admits, “because the Walking Woman cut-out which is in every shot is always static.” At every turn in his work, it gets a bit more complicated.

In one way, we send ourselves on a critical fool’s errand in attempting to explain the workings of his imagination. At best, we can only observe it happening. Snow’s protean character can be explained by applying his own understanding of the operations of free improvisation. “You just play,” he says. That’s also what he does with his art; he just makes it. Snow claims that one of the wonderful things about this method of playing music is its immediacy: “It is absolutely of the moment.” His praise is a kind of self-description. At 87 years of age, he makes a fool of time since he, too, is absolutely of the moment.

The following interview was recorded on October 31, 2015. Michael Snow will be in Winnipeg on January 27th, 2016, for the 25th anniversary of the New Music Festival. He will present a talk about “Snow in Vienna,” his 2012 piano performance from Fields of Snow, a documentary-in-progress, directed by Laurie Kwasnik.

Creative Canadian Music Collective (CCMC) at Arraymusic, Toronto, 2015. Michael Snow, piano; Paul Dutton, vocalization; John Oswald, alto saxophone; John Kamevaar, electronic percussion. Photo: Mani Mazinani.

Border Crossings: How do you decide which of your aesthetic hats to put on when you make a piece?

Michael Snow: The medium is arrived at for different reasons each time. I am a bit of a purist. For example, I had a sculpture retrospective at the AGO last year and it didn’t include any moving images. It was strictly the art of objects, so it was quite pure in some ways. I don’t really make mixed-media work.

You perceived the various iterations of the “Walking Woman” through a jazz lens. You said you were thinking about theme and variation. The Walking Women that I made from 1961 through 1967 were a sequence of variations within the same form. I thought in the beginning it was a little bit like jazz in that while many things could be done within it, I would always respect the original form.

When I look at a book like 56 Tree Poems, what comes to my mind is the question of rhythm. I thought you were composing that book. What was the thinking behind the way it took shape? It was definitely composed. I shot the photos and assembled them in a certain order according to the characteristics in the individual photos. They’re photos but they are very much like drawings.

We use the word composing to describe the conscious arrangement of marks and shapes on a painted surface and we also use that word to describe the arrangement of notes in music. The word composing seems especially applicable to you. I think that is true.

Your mother was a pianist, so was there constantly music in the house as you grew up? There wasn’t a prevalence of music in the house, she played only occasionally. Sometimes when there were modest family gatherings of two or three people she would play, but that was quite rare. It was strange because she really was very good; she could execute almost anything and she could read well. She could play the Goldberg Variations, which has some difficult fugues in it and I remember her Debussy La Cathedrale engloutis. But she didn’t play frequently. She did want me to study piano, though, and I wouldn’t do it.

So you start playing piano alone without benefit of lessons? I had discovered Jelly Roll Morton but it was ensemble playing I heard on the radio that really moved me. I wanted to do something like that. There was a radio program called At the Jazz Band Ball, which was part of the 1010 Swing Club. It was assembled by Clyde Clarke whom I got to know soon after I had discovered his radio program. He was very knowledgeable about the beginnings of jazz, especially the early ’20s, and he played some interesting things. But my mother was right, in a way; I should have taken piano lessons. As it turned out, I started to play the piano because I was inspired by the music I was listening to. I was teaching myself and in the first year I met Ken Dean, who played trumpet in the school band. We played together and we met some other guys who were interested in the same kind of music and the next thing you know there were bands. I was 19 years old. But you know, when I graduated from high school I also won the art prize, which seemed to say that I was good at art. I didn’t really know that and so I went to the Ontario College of Art, but I continued to play and when I was at OCA I met Bob Hackborn who was taking the same courses I was. He was a jazz drummer and he played with Ken Dean as well.

Michael Snow, Jazz Band, 1947, photo dyes on paper collage on board, 40 x 30 in.

Mike White’s Imperial Jazz band at the Westover Hotel, 1958. Ian Arnott, clarinet; Ian Halliday, drums; Mike White, cornet; Bud Hill, trombone; Peter Bartram, bass; Michael Snow, piano.

Wasn’t your prize-winning art piece a drawing of an ensemble of jazz musicians? No, there wasn’t any “prize-winning art piece.” What you’re referring to is a tempera painting, very Picassoid, that I did while I was in high school. It was partly portraits of some of the guys I was playing with. When I went to Europe in 1953 I went with Bob Hackborn. The trip was completely crazy. Bob brought his entire drum set—bass drum and all that stuff—and we went by boat on the USS United States sailing from New York. I had just started to play trumpet, which I brought, and I was a terrible trumpet player. We were staying at the Maison des étudiants canadiens in Paris in the Cité Internationale Universitaire where we saw an ad posted on a board that said a band was looking for a drummer and a trumpet player. So we auditioned and the guys in the band were knocked out by our playing and the next thing you know we’re in a band. It was comprised of all black guys from Guadeloupe, and a couple of other places. They had been contracted to play for the Club Méditerranée, which was about two or three years old at the time. It had a number of very primitive resorts in the Mediterranean area. So we went by train to Italy where we played in these resorts.

If you were such a bad trumpet player what was it that would have impressed the members of the band? They played a whole world of music that I didn’t know anything about and we played jazz and I think they were just impressed by the jazz. It was something they didn’t do, so in a way, there were two bands. I was only capable of playing two or three things, so I played them and the rest of the time I got drunk and tried to get laid. The trip to Europe was about trying to be an artist. Bob and I had both graduated from OCA and I had worked in an advertising firm for a year and was terrible at it so I decided I wanted to see more and go to museums and try to work in Europe. There were other people from OCA we met over there who had the same idea, so we criss-crossed with them. We knew a trombone player named Dave Lancashire, from Toronto, and he turned up in a band. Bob and I were hitch-hiking and in Brussels we went to a jazz club, La Rose Noire, where Dave was playing with a Belgian band. I asked if I could sit in and when I came off the stand the owner of the place came over and offered me a job.

Were you getting any better on the instrument? I played piano in the Brussels band. As for the trumpet, If I do say so myself, I got to be pretty good. But that was years later when the CCMC [Creative Canadian Music Collective] was formed and I started to really do some work on it. There are a couple of CCMC recordings that have some good trumpet playing on them.

But from 1959 to 1976 when the CCMC started you were basically a piano player. Yes, I was playing professionally with a Dixieland band led by Mike White and we played at the Westover Hotel for about a year and a half and were quite successful. We did some TV shows. I played with them every night and during the day I was in my studio and doing some interesting work. There was a lot happening. Mike’s band had Larry Dubin in it, who was eventually in the CCMC. He was the first free improvisation drummer I ever heard. I occasionally played with the Artist’s Jazz Band, which was the first free improvisation band that I knew about. As far as I knew, there was no free improvisation being played professionally in Canada at the time. The Mike White band was a trad band.

You liked playing, obviously, but it was also paying the bills. A practical necessity got mixed in with living the life of an artist. That’s true although I didn’t think of it that way. I thought I was lucky to be able to do it and carry on with my art, which was getting some attention. I was having shows and occasionally things sold. But there was another thing connected with the band. Mike had the idea to invite visiting guest stars over the period of the year or so that we played together. American musicians like Cootie Williams and Rex Stewart, extraordinary trumpet players who had played with Duke Ellington for many years, would come up from New York. And Vic Dickenson, a truly fantastic trombone player, played with us. Musically, it was terrific and the guys were wonderful people to hang out with.

And you didn’t think of these as separate worlds? They certainly were. The art was one thing and the music was something else.

When you went to New York in 1962 didn’t you have the idea that you would leave music behind and focus exclusively on your visual art? Yes. I had decided that if I did go to New York that I would try to concentrate on visual art and not play music. Admittedly, I had made that vow in the past but this seemed like a good time to try it. We had been following what was going on in New York in the art magazines, mostly Art News, and we were making trips every few months to go to galleries and see shows. I realized that if I really wanted to get better at what I was doing, it would be a good idea to be in New York.

There is a particular irony connected with that move because you go there thinking music is going to play a less significant role in your life and then you buy a piano from Roswell Rudd, and your loft becomes the centre for the most progressive music being played in the city. It’s true. I didn’t play with any of the people who used that piano, like Paul Bley, Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry and Albert Ayler. I was just a host. It was when free improvisation was starting to happen and I was interested in it but I didn’t know how to do it, so I was just learning. I could understand what principles they were using. Jazz is pretty simple in the sense that the band plays the tune and then you have a series of solos on the chord changes of that tune, usually two or three people in the band will play lengthy solos, and then you play the theme again. That was the way it was from the beginning. I always understood the kinds of variations that people were making because I understood what the theme was and so you could be impressed by the ideas that people came up with but it was based on what material was being used. They were playing such and such a tune, which had these particular chord changes. I went to hear Sonny Rollins a couple of times and what was interesting about his playing was how inventive he was in adding new kinds of harmony to the existing chord changes.

CCMC Volume 1, 1976, 33-1/3 RPM vinyl record, Music Gallery Editions. Photo: Mani Mazinani.

So free improvisation is a process and not a style of music? Yes, that is the way old jazz was played, and probably still is, but free improvisation is something else completely. You just play.

So it can go anywhere? Absolutely. The fact that it can go anywhere makes the players into simultaneous composers. The CCMC was formed partly out of the Artists’ Jazz Band and one of the things we wanted was to have as varied an instrumental source as possible. The CCMC started the Music Gallery as a place for new music to be played and as a place for us to play. For a few ideal years it was wonderful. We had two grand pianos; we had two Fender Rhodes pianos; we had synthesizers; we had xylophones and vibraphones and many percussion instruments. Our ambition was that everybody played several instruments, so you had this huge talent base from which to choose. It was really quite fantastic because, for example, you could have four pianos.

You have said that in the Artists’ Jazz Band nobody could play and that playing it wrong was better than getting it right. The Artists’ Jazz Band didn’t necessarily try to play tunes; they just played. It was totally free improvisation based on their level of jazz appreciation and their absorption in qualities of sound. Bob Markle played tenor and he was influenced by John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, but he was a total amateur in the sense that he couldn’t come up with knowledgeable harmonic variations like they could. But in his own way, he represented them just from sheer love. The Artists’ Jazz Band was a revelation for me in a way. We were all painters, mostly at the Isaacs Gallery, and good friends, but I had worked as a professional musician and I was a bit conceited. At first I thought it was amusing that they were playing but it didn’t take me very long to realize how good what they were doing was. I thought, How come this is so good? and I realized it was simply that they had the freedom to try anything; they weren’t trying to get something right. Then members of the Dixieland jazz band I was playing with, like Larry Dubin and Terry Forster, a wonderful bass player, came to the Artists’ Jazz Band sessions, it was the same sort of revelation for them as it has been for me. In fact, Larry had been playing free in the sense that he was a drummer who constantly drummed. He was obsessed with it. He told me that to practise he would sit in his apartment and play with the traffic sounds. He could play very good conventional jazz but in free improvisation the drummer can go anywhere, just like the other instruments can go anywhere. The next thing I knew I met other people, like Al Mattes, who wanted to free improvise, and Nobuo Kubota, who was also in the Artists’ Jazz Band. They joined the CCMC with me. The CCMC was a more formal recognition of free improvisation.

Michael Snow, film still, New York Eye and Ear Control, 1964, 16 mm film, 34 min., black and white, sound.

You said playing solo wasn’t radical enough. Did you find the radicality you were looking for in playing with these guys? Yes. The Artists’ Jazz Band were amateurs and yet there was this miracle that given a particular occasion and enough stimulation, they could play absolutely great music. On the recordings that the Isaacs Gallery and the Music Gallery Editions put out, there is plenty of evidence that the music is sensational. What was miraculous for me was that I learned to just play from them. You listen to yourself and you listen to what else is going on around you and you are affected by it. I found when I was in New York and heard Albert Ayler for the first time, it was a knockout because I realized that even though they played these little tunes that he composed, the improvising was pure, like the Artists’ Jazz Band. That’s when I made the film called New York Eye and Ear Control.

It’s unrepeatable isn’t it? It can’t be done the same way because there is no score? Yes. One of the wonderful things about it is that it is absolutely of the moment.

You had a preference for working within containing structures. This way of playing guarantees that there is no container to begin with. Being in the moment is the only containment? That’s right. There had been all kinds of excitement in the ensemble playing in the jazz groups I played with, but we were thematically restricted by what we were doing, by the material that we were working with. There would be these surprising discoveries, like the ones I mentioned with Sonny Rollins. But with free improvisation it is all new and you are recognizing it as it comes into existence.

You said that when you went to New York you were surprised that the worlds of painting and sculpture had no connection to the orbit of experimental film. Did the music world at that time in New York share a similar kind of isolation from other artistic practices? Yes. The kind of music that I ran into and was interested in had very little public. There wasn’t much work for that kind of music.

It is interesting that you were an active participant in all those worlds. Was that a kind of schizophrenic existence? It’s a good question. In a way I think New York Eye and Ear Control was an attempt to bring together those two things, to make a simultaneity out of free improvisation music and a composed moving image. This is a bit more complicated than that because the Walking Woman cut-out which is in every shot is always static.

Because what you recognized was that the relationship between sound and image situations was largely unexplored territory? Yes and Eye and Ear Control really brought that to my attention. In subsequent films, like_ Wavelength_, Back and Forth, Standard Time and Rameau’s Nephew (which is a “talking picture”), the sound part was really important, but it was making Eye and Ear Control where I recognized that as a whole area. A record company once asked me if I would be interested in having the soundtrack of Wavelength issued as an LP. I said yes but it never happened.

Let’s talk about the documentary film Laurie Kwasnik is making about you called Snow in Vienna. In it you play a solo piano performance at the Wiener Konzerthaus in 2012 and what is amazing is that you seem to get younger and more invigorated as you play. That might be a reflection of the fact that it is going well. Laurie Kwasnik has been working on a film about me as a musician for several years. She has shot many interviews with me and musicians I’ve played with and many concerts in Canada, the U.S. and Europe. “Snow In Vienna” is a chapter in her film Fields of Snow.

How do you know that it is going well? What are the indications that give you that recognition? Well, I’m listening like someone in the audience is listening and I get to appreciate or disagree with things that I play.

So you then have the option to play something more agreeable? To counter it in some way, or to develop it into something else. It’s not exactly a conversation, but just as someone in the audience is hearing this thing unfold, so am I as the player. But I can alter the direction, so if something really works and affects me as a listener, then I’ll try to develop that.

New York Eye and Ear Control, 1965, 33-1/3 RPM vinyl record, ESP Disk. Music by Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, John Tchicai, Roswell Rudd, Gary Peacock, Sonny Murray. Recorded by Michael Snow. LP jacket designed by Michael Snow. Photo: Mani Mazinani.

You are player and listener, audience and generator? Yes, that’s true.

I heard small echoes of Aaron Copland in your playing. That’s possible.

I like the way you cup your hand and strike the keyboard. It makes the piano into an even more percussive instrument. These techniques you have developed over the years are like gestures, the equivalent of mark-making in painting. Yes. Playing the piano involves the effect of hand gestures, so anything that the hands can do on the keyboard, or on the piano, is a possibility. The Bösendorfer which I play in “Snow In Vienna” has more notes in the bass—it’s not as much as an octave—but there are another six notes and I tried to exploit those.

How do you prepare for a solo performance? Do you have to get your mind in a certain frame? It’s kind of contradictory in some ways but if I’m playing solo I prepare for it just by playing and discovering certain things and elaborating on them privately so that they’re now in my memory. When I play solo it is not entirely new; it can be based on things I have done before, but they come up in a new way; it’s a kind of on-the-spot composition.

ichael Snow, film still, Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen, 1974, 16 mm film, 270 min., colour, sound.

Aesthetic memory functions in interesting ways. Ginsberg lifted an idea from Kerouac when he said that “mind is shapely.” He seems to be getting at the idea that even though we think we are operating in some chaotic space or time, there is a way in which the mind will always insert itself in the making of art. The thing is, in playing you might include something similar to what you have played before but what you want to develop in it is whatever is new. Because you play for yourself first. It’s great if there’s an audience but I don’t think about the audience; I just think about the music. The necessary concentration—and it is both physical and mental—has to be on the music. Playing with an ensemble is a different thing from playing solo, one is sometimes surrounded by surprise.

At the end of your encore in Snow in Vienna you say, “I think that’s the end.” It’s as if you weren’t sure. I think I meant that I would play again.

You also said that you are still playing the blues. Have they been so instrumental that even though you have moved on, you’re still in that world? I guess so. The way I play has developed over so many years and it is partly the result of the influence of the people I have played with; playing with John Oswald or Paul Dutton is a particular experience that has affected my own playing. The 12-bar blues was the most open form in early jazz where you don’t have to play a theme, you can just play the blues. It’s where the most free improvisation took place in the early years of jazz and it was influential in that way.

I’m attracted to your idea that one of the things the artist has to be involved with is “the conversion of mistakes.” Is it better to start off on the wrong foot rather than the right one, so that you can engage in that conversion? I think you can only make a mistake where there are rules, but you can make a mistake of intention where you gesture to play a certain note but you hit another one. That would simply be an aspect of paying attention. So you convert it to a positive gesture in some way. That’s part of the ongoing listening the player has to be involved in. Whether you consider it a mistake is contextual.

You said that you were interested in making art that adds to life more than you were in making art that comments on life. What is your sense of the role music has played in that life-additive dimension? Improvised music is definitely putting something there that wasn’t there before. It is an experience in time-shaping.

Michael Snow, film still, Michael Snow live in Vienna, 2012, digital video, 34 min., colour, sound. Film still: Laurie Kwasnik.

When we began this conversation you talked about being a purist in the organization of your sculpture exhibition last year. Am I right in thinking that music is the purest thing you do? Improvising music is a particular kind of experience. The making and the object that you are making are simultaneous. In all other mediums, for example sculpture, there’s a separation between these stages.

In 1967 you said you were sorting out what you called “the conflict between the romantic and the classic.” Have you figured it out by now? I can’t understand the distinction now. I guess you can say that free improvisation is romantic and oddly enough most of my artwork, certainly the sculpture and most of the films, is composed. And in one sense that is classical. I think Wavelength can be described as a classical shape.

Music has been at the centre of your life all along, hasn’t it? Yes it has, even when I have tried to give it up.

So music has been more loyal to you than you have been to it? That’s a good way of putting it. ❚