Picasso Remixed

by Barry Schwabsky

Rewind the tape to the fall of 2019—also known as the year One BC (Before COVID). In New York, the Museum of Modern Art opened its redesigned and expanded building with a new, more flexible approach to displaying its collection, one at odds with its former effort to delineate a single authoritative canon and timeline of modern art. And yet there was one thing to which the museum seemed to hold fast from its former ideal: the centrality of Pablo Picasso to the very idea of modern art. If previously overlooked and undervalued artists, styles and traditions were going to be brought in under the umbrella of modernity, it would be thanks to a perceived propinquity to the stylistic licence granted by the shape-shifting Spanish genius. Example: To give new importance to Faith Ringgold’s monumental canvas of 1967, American People Series #20: Die, meant placing it in proximity to Picasso’s works, using it almost as compensatory substitute for the still-lamented Guernica, which had been asylumed there at MoMA until it finally arrived in Spain in 1981.

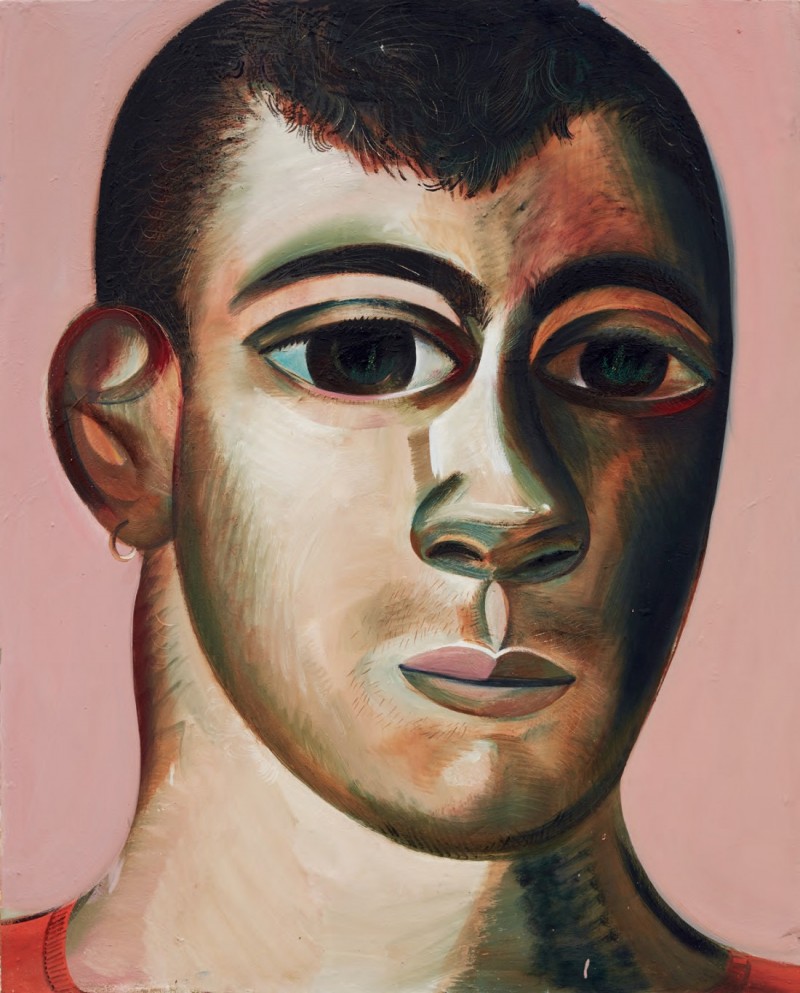

Louis Fratino, Me, 2019, oil on canvas, 60 x 48 inches. © Louis Fratino. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Back when Ringgold painted Die, MoMA would probably have looked instead to Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg or Frank Stella as Picasso’s rightful American heirs—and, big questions of gender and race aside, that means working with a different idea of history and artistic influence, one in which the upshot of cubism would have to be semiotics, material heterogeneity or abstraction. In a recent reconsideration of the work of Donald Judd in the New York Review of Books (December 2020), David Salle aptly summed up that time as one “when it was still possible to imagine internalizing all of art history and distilling from it a correct analysis of the way forward. It was as if finding the right path was akin to cutting the Gordian knot, the bold stroke that once and for all resolves a vexing conundrum.” For Judd, Jackson Pollock would have been the most immediate emblem of this problem to be violently addressed, experienced, Salle continues, “as a kind of trauma, in much the way that the relentless innovation and reinvention of Picasso had taunted a previous generation.” The only way to become a historical successor to a Picasso was to transcend him completely. Today, neither Pollock nor Picasso inflicts any traumas on younger artists.

…to continue reading the article by Barry Schwabsky, order a copy of Issue #156 here, or Subscribe today.