Painting in an Expanded Field

An Interview with Laura Owens

Is it too early to refer to the Owens Effect? I’m describing what happens when a single artist gathers up the traceries of what an art form has been and the trailings of what it has become in the digital age and presents what she makes out of the commingling as some kind of new and generative pictorial language. There is evidence that others are tuning in to this possibility. Discerning critics like Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker and David Salle in the New York Review of Books have come to similar prognostications: Schjeldahl says that Laura Owens’s “genius of revelations” has revealed “that what seemed a formally exhausted state of painting could be a garden of unlimited, freshening delights,” while Salle praises the “continuous run of invention and forward-thinking bravado” that makes her work “the apotheosis of painting in the digital age.” Both are unqualified in their enthusiasm for what they see in the 48-year-old Los Angeles painter’s faultless trajectory. She has been a steady star in the firmament of her own making. Owens is something of a painterly Midas: everything she touches, touches on something else. She understands the art of painting as an act of transition: the painting moves towards the book; the autonomous painter, towards group collaboration; the manner of exhibition, towards a matter of intervention. Owens gravitates towards the idea of painting as an expanded field that confounds our expectations, a way of making art that runs the risk of being misread. In plotting a map of misreading, she insists upon a must of misreading.

Laura Owens, Installation view, “12 Paintings,” 356 S Mission Rd, Los Angeles, January 20–July 7, 2013. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Owens is both rigorously conceptual and sensuously perceptual. This fluidity allows her painting to go anywhere and become anything. In her figurative works she reprises a bedroom intimacy by Henri de Toulouse- Lautrec, or delicately shifts the power of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s gaze on a courtesan into the woman’s gaze out at the viewer. (In this fraught age it is worth remarking that the look out has considerably more erotic charge than the look in.) Her drawing of St. Sebastian mimics the attenuated manner of El Greco but uses arrows with fletching as transparent as dragonfly wings. And in an early drawing called Falling Out from 1993, she pairs an upside-down baby with a mother figure spidered out of Louise Bourgeois’s nursery. Owens keeps us in a state of multivalent surprise, and the feeling you come away with is not always pleasing.

When she works with abstraction her effects are dazzling; the combinations of handmade, silkscreened and digital mark-making in exhibitions like “Pavement Karaoke” at Sadie Coles HQ in London, “Ten Paintings” at the Watts Institute in San Francisco and “12 Paintings” in her own former space at 356 S Mission Road in LA are staggering in their verve and beauty. She turns what should be vexatious surfaces into vivacious ones. She says that if painters want their medium to stay relevant, they have to show painting’s elasticity, its infinite possibilities, and that it can stand a lot more abuse than people believe. In this regard she uncompromisingly sits her own paintings on her knees and abuses them for their own good.

The sense of freedom that emanates from her work is exhilarating, because of what she achieves and because of what she risks in the achieving. In the following interview she admits that for reasons both deliberate and unconscious, she had avoided trying certain things in her paintings, and the realization that they were doable revealed wholly unoccupied imaginative spaces. “It’s as if you’ve just opened a door to a new series of rooms that you didn’t know existed in your house. What had seemed to be a small closet, something I’ve been passing by, turns out to be a serious addition.”

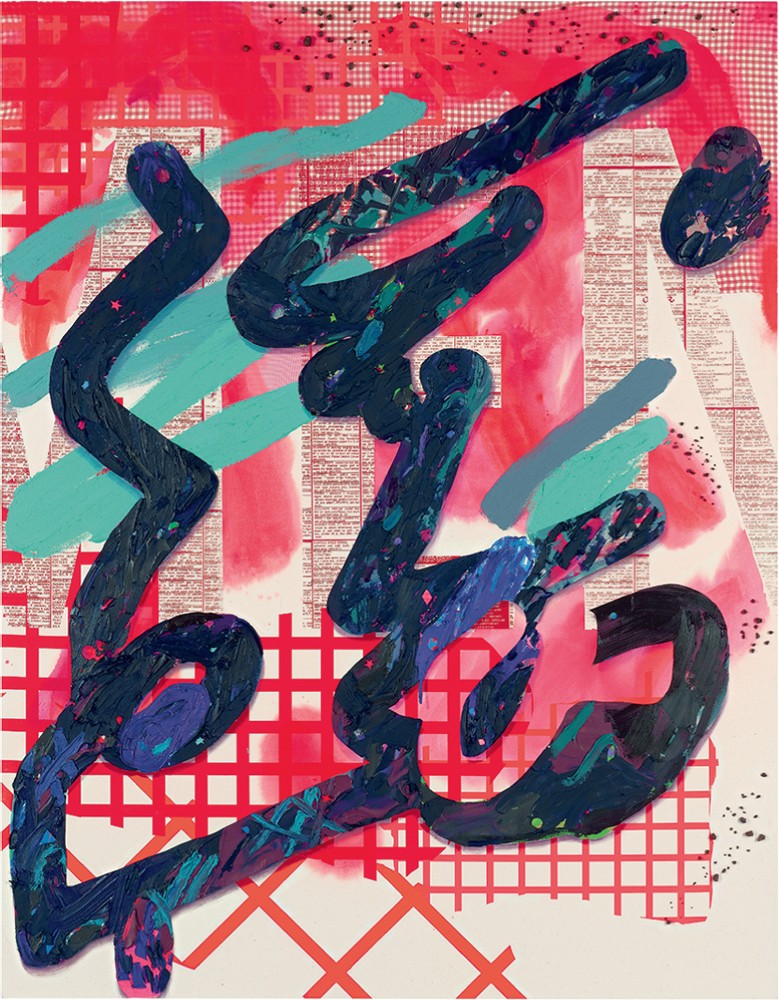

Untitled, 2012, acrylic, oil, Flashe, resin, pumice and fabric on canvas, 108 x 84 inches. Photo: Prudence Cuming.

Looking at her paintings and drawings is like encountering great poetry; the metaphors and the associations they make for us are promiscuously layered and precisely measured. Her paintings are less visual free verses than they are ghazals of casual complexity.

In 1920 the poet Ezra Pound fabricated a double for himself in the character of Hugh Selwyn Mauberly, a man utterly out of joint with his time. He recognizes that all periods ask for a telling representation: “the age demanded an image / of its accelerated grimace,” Mauberly tells us. The age we live in asks no less of us, and in Laura Owens it has found its image maker. In her uncompromising and bewildering art, she is effectively delivering to us images of our accelerated promise. “Laura Owens,” a mid-career retrospective organized in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, will be on exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, from November 11, 2018, to March 2019.

The following interview was conducted by phone to Los Angeles on January 26, 2018.

Border Crossings: One of the early entries in the remarkable catalogue for your Whitney exhibition is an essay by bell hooks in which she argues the necessity of recognizing a multiplicity of voices in poetry. Is it positioned where it is because you are advocating an equivalent need for a multiplicity of voices in painting?

Laura Owens: Deborah Kass was a teacher of mine at Rhode Island School of Design, and the experience of meeting her and having her compose a feminist painting course in a department and a college that was very conservative was an incredible moment for me. bell hooks was one of the primary texts we were reading. So chronologically her essay is early in the catalogue because that marked my introduction to the idea of multiple voices. I think I was 19 or 20. It played a part in my thesis at RISD, as well as in my application to CalArts, because her voice was so influential to me and to a lot of women at that time.

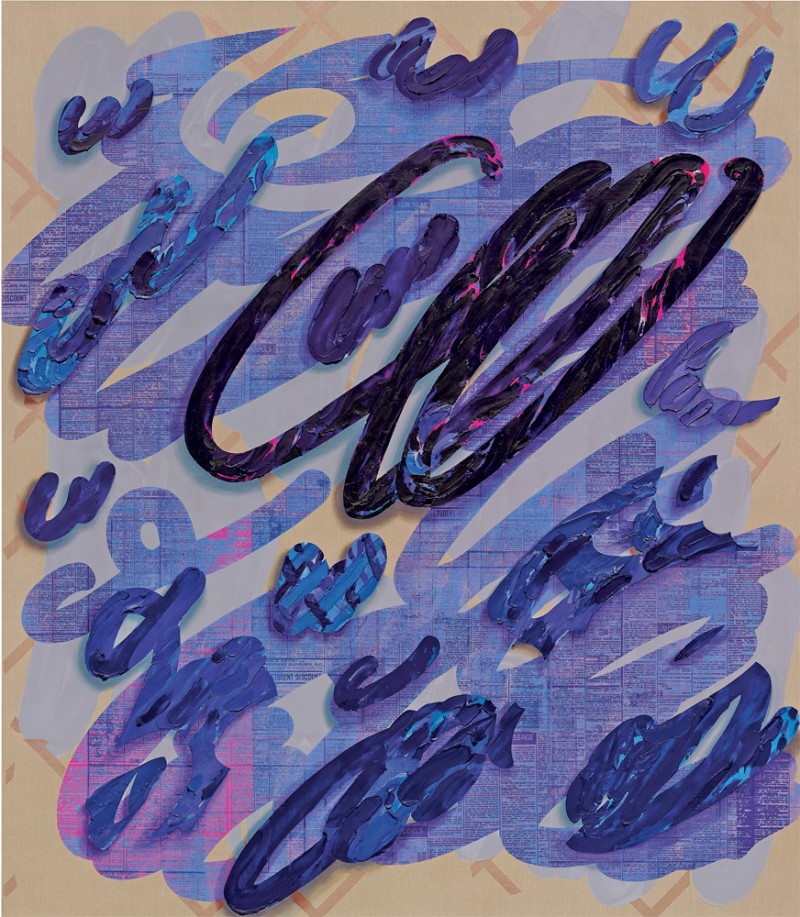

Untitled, 2013, acrylic, oil and Flashe on linen, 137.5 x 120 inches. Photo: Douglas M Parker Studio.

From what I’ve read, your experiences at RISD and CalArts weren’t entirely congenial. Did the attitudes at both those schools strengthen your resolve to resist the kind of aesthetics you had run up against?

There was congeniality, but in different ways at each school. At RISD it was among the students. We really bonded together, and we had a thirst for knowledge outside of what was being presented to us. We petitioned to have outside voices come in, like Deborah Kass, and then we made our own list of visiting artists and found the money to get those people into the school. So there was a kind of camaraderie and togetherness. The rigid way in which painting was viewed at RISD forced us to create a discrete community. CalArts was very different. No particular aesthetic was being promoted. There was more of a demand that each student assume the position of an established artist from the get-go. You had to be walking in there with a position, and there were really diverse positions all around you. Those differences existed both in the faculty and in the student body. So there was a pressure to be articulate in a way that diverted from, or corresponded with, any number of existing positions in the school. It was more isolating because there wasn’t the same kind of community as I was describing at RISD, but it did force an inner growth that I wouldn’t have achieved on my own for a long time.

And yet you were doing installations at CalArts as if you were a secret painter. Was that because there was a recognition within the faculty that painting was a dead art form and that it wasn’t the sort of thing a contemporary artist should be doing?

That was never articulated by anyone in the faculty, and my painting wasn’t that much of a secret because I would have them in the studio. There were also other students who were showing paintings. In fact, very early on, Monique Prieto and I did a group exhibition and it showed how many people were making paintings, although not claiming that as their primary work. The faculty wasn’t so reactionary that it would condemn a particular medium. But they were suspicious of market orientation and galleries and institutional structures. I had been making installation art at RISD and I continued to do that because it was easier to talk about. The whole emphasis of CalArts is on discourse rather than studio practice. Even though everyone has a studio, it is a post-studio school, and a studio might look like an office. When people were presented in a critique with painting, half of them would revert to, “Well, I don’t know anything about painting, so I can’t say anything here.” I still find people like that, who assume there is some sort of historicity about painting that forbids them access to it, or who end up being slightly feeble in attempting to say something because they have a preconceived idea that other people are more authoritative about painting.

Untitled, 2000, acrylic, oil and graphite on canvas, 72 x 66.5 inches. Photo: Tom Powel.

In 1992 you did an installation at the Mint Gallery at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia that was entirely in pink. I was thinking, there have been women painters who have used that colour—Niki de Saint Phalle, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler and Mary Heilmann—but it seems to have been used most often by men: for example, Guston in his abstract impressionist phase, or de Kooning. Was pink a gendered colour for you, in any way, when you did that installation?

Basically I was thinking about gift shops and places where things are commodified, or become gendered objects, whether a tablecloth or certain types of illustration. So there were text pieces in that installation from a children’s nursery rhyme, which were sort of hidden in the wall. In Rhode Island there was a large chain gift shop/ craft store called Ann and Hope, and I would go there for art supplies rather than to the art supplies store. I was trying to make art out of a readymade ensemble that had been created in a very gendered way. But because I had come from RISD where I was taught a Hans Hofmann-style formalism, the paintings I made around that time were also definitely referencing Guston and de Kooning, as much as Fiona Rae, Mary Heilmann and other women painters.

My inclination is to ‘read’ your work, partly because you make multiple references to language and alphabets, and I think in particular of the series of paintings based on the story of the cat and the alien that you had asked your son to write for you. Is that a legitimate way to talk about your work, to say that we read it as much as we look at it?

I’ve certainly thought about reading as one of the ways that we look. I recently made a series of newspaper paintings. You can go up close and literally ‘read the painting’ if you want to know what the details are, and then an image of some story might come out, or a reference to something outside the literal image might emerge—something distinct from the image or text you’re looking at. Early on I would try to make a painting out of the various pieces and parts of heterogeneous materials and images and references and marks, and I was asking the viewer to do some work in understanding why these things were on the same surface. At first it wasn’t always evident, so you had to look and fill in the spaces in some way.

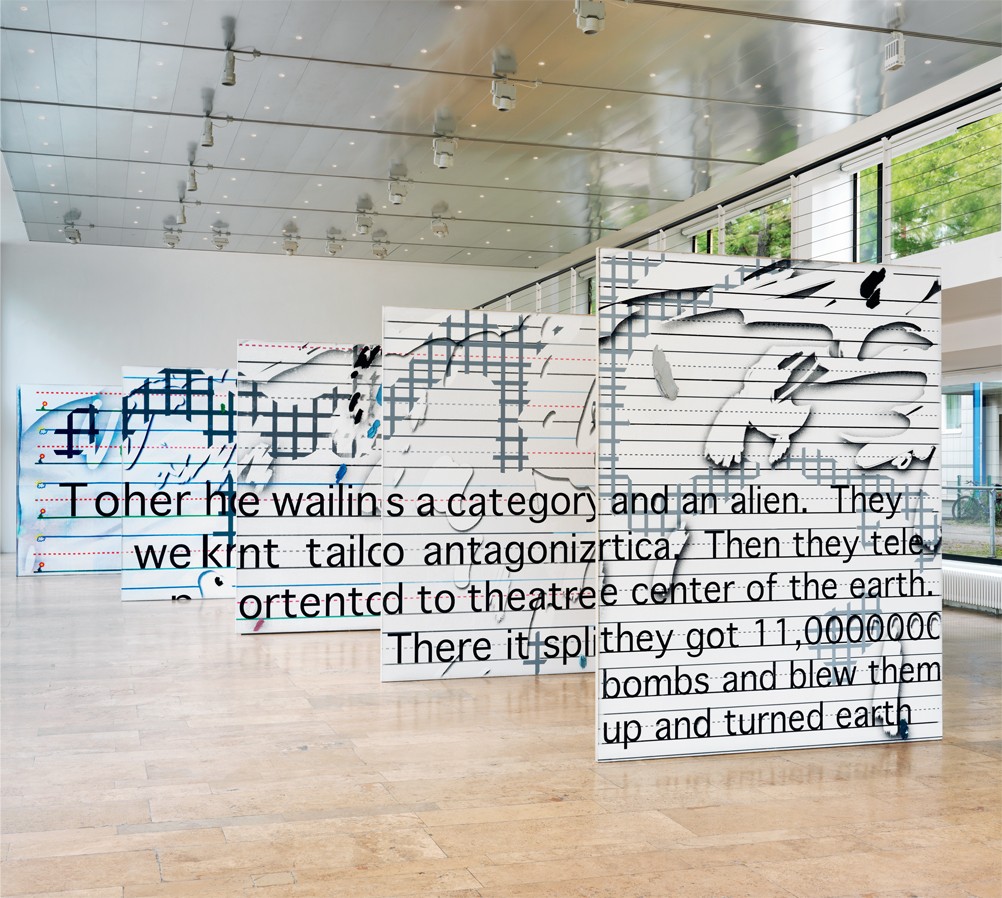

Untitled, 2015, acrylic, oil and Flashe on linen with powder-coated aluminum strainer, 5 panels, each 108 x 84 inches. Installation view, Capitain Petzel, Berlin, May 1–August 22, 2015. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

In that recent body of newspaper work, the reader/ viewer has an awful lot of fun because of the nature of the content. I liked the paintings referring to the Sentient Jets and Shoe Dazzle, and my favourite was the article on Ronda Rousey, the Ultimate Fighting Champion, “who sleeps naked and is unapologetic about breaking the bones of her opponents.” Obviously those works involve an increased engagement with the reader.

Yes. I feel that the artwork is co-created by the viewer. I have always thought of it that way.

For the paintings in your “Secession” exhibition in 2015, you used a 1942 Los Angeles Times as the background. There seems to be less mark-making and activity on the surface, here, than in other series.

Maybe that’s to clue you into the fact that I spent several months editing the newspaper itself, with all its images and the fonts: I acted more as a graphic designer or newspaper layout person for that series. That’s where the hundreds and hundreds of decisions in those paintings are getting made. I should add that the backgrounds come from a set of newspaper stereotype plates that had been repurposed as flashing beneath the shingle siding of my house. These paper negatives were originally made to cast the lead cylinders used on press, and they all came from editions of the Los Angeles Times printed over a one-month period in 1942—so the background isn’t from a single newspaper.

I think in an earlier interview you said painting had to “expand its own linguistic edges.” I have a sense that you have always wanted to take the art form and put real pressure on how it functions. Is that what you’re after, to push things as much as you possibly can?

I have always had this feeling, I don’t know why, that if you want painting to stay a relevant medium, then you have to show its elasticity—its infinite. In order to keep painting relevant, it’s everyone’s job to show that. I definitely feel that the question for me, and the way that I approach painting, is to ask myself what I haven’t been putting in a painting, and why I shouldn’t try to put that thing in.

And that becomes a conscious recognition? You say to yourself, “This needs to go in because it hasn’t been in before.”

It’s not necessarily because it hasn’t been in before, but more because it’s counterintuitive for me to put it in. It’s quite possible that something has been in before, but hasn’t ever been associated with my thinking about painting. It could be very personal. So for example, very early on, it was the figure. I forced myself to put the figure in, because I hadn’t been thinking about it as a possibility in the paintings that I was making previously.

Was it freeing to move towards figuration?

I don’t know if it was freeing, but it is reassuring when you think you can’t do something or when you haven’t been doing something for a reason, or when you’ve unconsciously not been doing something, and then you realize that there is a way to do it. It’s as if you’ve just opened a door to a new series of rooms that you didn’t know existed in your house. What had seemed to be a small closet, something I’d been passing by, turns out to be a serious addition.

…to continue reading the interview with Laura Owens, order a copy of Issue #147 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!