Painting by Numbers

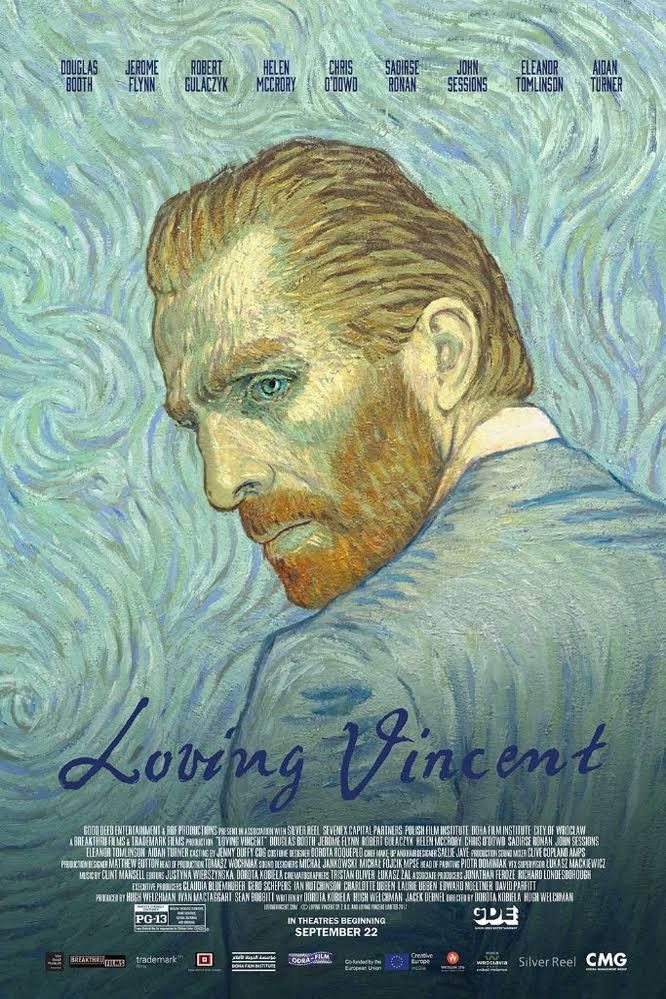

“Loving Vincent,” directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman

There is a kind of film, like Russian Ark and Avatar, that, because it exhausts the conceptual, narrative and technical possibilities of its type, needs to be made only once. As the world’s first fully oil-painted, 95-minute-long feature film, Loving Vincent seamlessly fits that category. It is set a year after the death of Vincent van Gogh in 1890 and uses as cast members and locations the people and places the artist painted during his lifetime.

The story is simple enough. Armand Roulin, the son of postman Joseph, is an aimless, quick-to-anger young man who is asked by his father to deliver a letter to Theo, the artist’s devoted brother. In the course of attempting to execute that simple request, he meets a group of people who knew van Gogh, including Pere Tanguy, his paint supplier; Dr Paul Gachet, Louise Chevalier, the doctor’s housekeeper, and his daughter Marguerite; Adeline Ravoux, the daughter of the innkeeper in whose inn Vincent stayed and died; and a tangle of supporting characters who made appearances in his paintings throughout his brief but productive life. Van Gogh picked up a brush for the first time in 1881 when he was 28; when he died in 1890 at the age of 37, he had made over 2,000 works of art, including almost 900 paintings, the majority of them in the last two years of his life.

The story may have been simple but its making was anything but. Loving Vincent took six years to complete. It involved shooting a live action film with flesh-and-blood actors and then having every one of the 65,000 frames painted by 125 professional artists. Live action became animation. To complicate the telling, the filmmakers placed all the scenes inside the frame of van Gogh’s landscapes, still lives and portraits. Loving Vincent is like a kinetic art exhibition in which van Gogh’s most famous paintings are re-presented as incidents in his life and evidence about the circumstances of his death.

These fictional reinhabitations of van Gogh’s paintings are the film’s most inventive scenes. They include the simplest encounters, like a quick cameo from La Mousmé, 1888, who says the reason she signed the petition to run van Gogh out of town was because “he was mad”; to the film’s opening scene where Armand is involved in a fist fight with a Zouave, a member of the French infantry that fought in North Africa and who wore distinctive uniforms with baggy trousers, a sash and a red fez. The portrait called The Zouave, painted in 1888, is in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. It is one of 94 paintings that are repurposed in Loving Vincent and that contribute to the film’s nature as a kind of postmodern fictional biopic.

The aftermath of Armand’s skirmish sets up a scene where the move from outside to inside takes viewers from the Café Terrace at Night into The Night Café, two of van Gogh’s most famous paintings. Armand and Lieutenant Milliet enter the café from the back and as they walk in, they pass a couple at the first table; then Armand poaches a mostly full bottle of wine from a patron who has passed out at the second. The barman is standing at the pool table and the clock above the bar says 10 minutes after midnight. The next time we see the inside of the café, Joseph has come looking for his errant son to find out when he intends to begin his mission to deliver the letter. His answer is provided in the details of the animated painting. Armand is slouched over a table at the front of the café; the couple has left; no one looks after the pool table and the clock reads 2:25. Armand has been drinking for over two hours.

Throughout the film this degree of scrupulous attention to detail is both admirable and obsessive. There are cases where the animation seems as interesting as the source painting itself. In his quest as letter deliverer, Armand walks along the Seine at Asnières, a suburb in the northwest part of Paris that is close to Theo’s flat in Montmartre. It is the location of Bridges Across the Seine at Asnières from 1887, a painting that shows a woman with a red parasol on the riverbank, a train passing along the bridge above her and a barge floating in the blue/green water. The original painting was done en plein air and uses short brushstrokes and a bright palette (Vincent wrote to Theo that it was one of a group of landscapes that he hoped people would appreciate for their “open air and good cheer”). To animate the painting, the filmmakers had to have the train come into and then pass out of the frame; the barge had to move behind the pier; and the woman had to move to the edge of the riverbank and look down at the water. It is an uncomplicated scene that would have taken hundreds of different paintings to reimagine as a moving sequence.

Characters are also introduced through the lens of van Gogh’s portraits. We first see Marguerite, dressed in crisp white, at her piano; Pere Tanguy is initially pictured inside his painting-lined shop, where he offers Armand a brandy before beginning to tell his version of Vincent’s life in Paris. (Whenever the film shifts from the main story to recollections and flashbacks, the palette goes from colour to images in black and white that are composed from contemporaneous photographs. The colour of memory in Loving Vincent is grisaille.)

The scenes between Armand (played by Douglas Booth) and Adeline Ravoux, the innkeeper’s daughter (played by Eleanor Tomlinson), are where the overlapping of the painted life and the fictional extrapolations from that life are most effectively realized. From Armand’s first sighting of Adeline, the meetings between them are charming and flirtatious. “That’s a fine dress,” he compliments her, “suitable attire for a proprietress.” Her response is a blushful “I don’t get to wear it often when my father’s here. He’s got errands for me.” In all their interactions, you can see evidence under the animation of nuanced acting, as well as in the scenes where Dr Gachet (played by Jerome Flynn) offers his explanation for Vincent’s psychic condition, and in the riverbank conversations between Armand and the boatman (played by Aidan Turner). All that performing is painted over. In Loving Vincent animation makes acting a pentimento.

What is lost in drama and sexual play between Armand and Adeline is gained through painterly substitution. When she pours him a cup of coffee, the film uses van Gogh’s Still Life with Coffeepot (1888) as its domestic setting. Van Gogh wrote in a letter that the still life was one “which I patiently worked out,” so the animated scene is attentive. It includes the fruit, the blue and white checkered milk jug and the stacked coffeepot. But behind Adeline’s body it obscures another cup and pitcher on the right-hand side of the composition. What it has to add is a cup and saucer identical to the one already in the still life into which Adeline can pour coffee for them both. The scene is a marvel of expanded reduction.

As it turns out, Loving Vincent is not really about Vincent van Gogh at all. It uses his life and work as a point of departure to tell a layered narrative that combines a detective story, a murder mystery and an investigation into the complexity of human motivation and emotion. It also recognizes that any story is as complicated as there are tellers to tell it. As he attempts to find out what really happened to Vincent and what was his psychological state when he shot himself, if he actually did shoot himself, Armand writes to his father that “strange things are happening to me here. People are on edge about Vincent, about what happened to him. Everyone has a different story.” The story that Armand settles on has its own complication in dealing with Vincent; he runs a gamut from hostility to sympathy, and from admiration to self-knowledge. Armand’s narrative is one of personal redemption. Through his quest, he comes to realize how a life can have meaning.

The first intimation of that awareness comes in a heated outdoor meeting he has with Marguerite Gachet, who asks accusingly, “You want to know so much about his death, but what do you know about his life?” Armand’s response applies to himself as much as it does to van Gogh: “I know that he tried hard to prove that he was good for something.” That sense of self-worth is amplified in the tête-à-tête he has with his father when they sit together under the nocturnal brilliance of Starry Night over the Rhone (1888). The painting, which is in the Museé d’Orsay in Paris, shows a couple walking arm-in-arm on an evening that is alive with light emanating from the buildings on the far side of the river and from the haloed glow of the multitude of stars that gives the painting its name. In the delicate animated recasting of the painting, the couple has been replaced by the Roulins, father and son. Armand, we have learned, has lost his job because of his absence, and Joseph asks him if he has had any luck finding a new one. “I’m good at fighting,” Armand says, and his father replies, “The Roulins have always been good at that, the trick is to know what you’re fighting for.” Then Roulin (wonderfully played by Chris O’Dowd) directs his son’s gaze to the light show above them and we hear read the contents of a letter sent by van Gogh’s widow to thank Armand for working so hard in his role as letter carrier: “In the life of the painter death may not be the most significant thing. For myself I declare I don’t know anything about it. But the sight of the stars always makes me dream. Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be inaccessible to us? Maybe we can take death to go to a star. To die peacefully would be to go there on foot.”

The words are van Gogh’s but they are understood as an answer to the question Armand has asked his father about Vincent: “What I’m wondering is will people appreciate what he did?” The starry night explodes into radial circles of lights, and those lights further transform into the Self-Portrait from 1889, in which van Gogh presents himself as handsome, elegantly dressed in a gorgeous blue suit that matches the colour of his eyes. The music underneath the undulating shifting and shaping of paint that we see is Don McLean’s “Vincent (Starry, Starry Night),” the monster tribute hit released in 1971. Rarely are pop songs perfect musical equivalents for film stories, but in this case McLean seemed to have written a love letter to Loving Vincent. The film goes to considerable trouble and expense of time and resources for Armand to come to the realization that life can provide an opportunity to show, as Vincent puts it in a letter, “what a nobody, a non-entity, has in his heart.” Whether the effort is justified or not, moviegoers will have to determine for themselves. Either way, it is a recognition they will come to only once. ❚