Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Oblique Strategies

Carmen Winant, Daidō Moriyama, Gabriele Basilico, Susan Meiselas

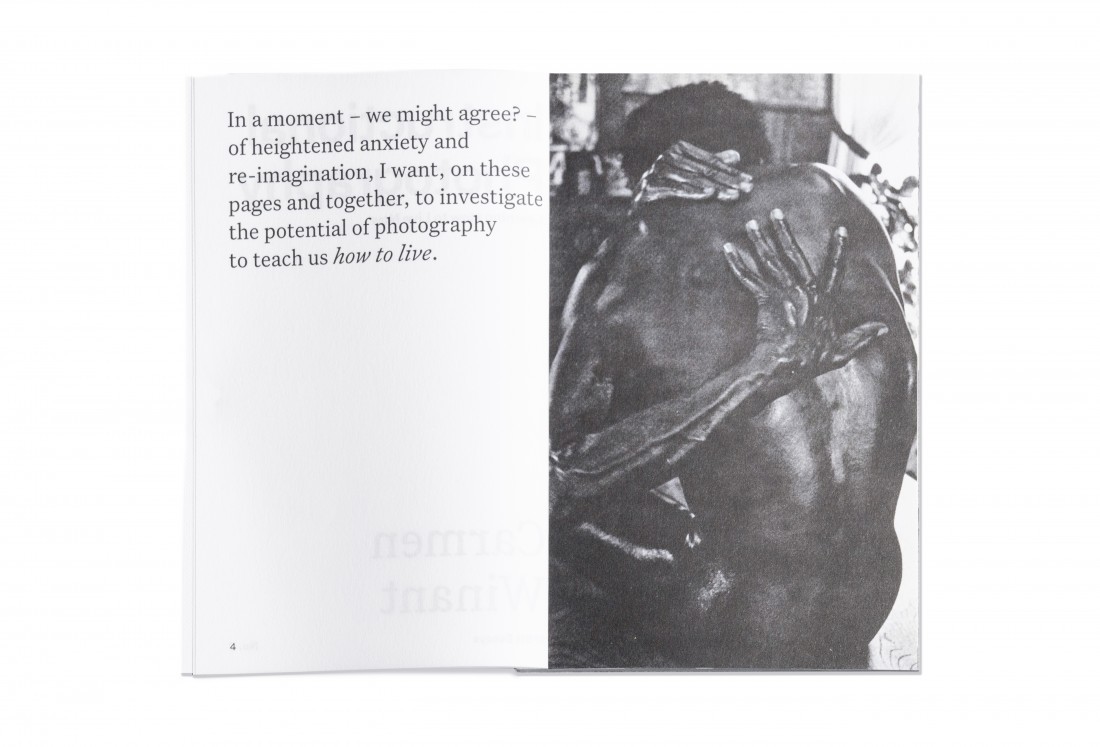

You don’t have to take photographs to make a photo book. Or, you can take them in the sense of laying hold of them, rather than of making them—which is to say, the strategy of the readymade. That’s what the Ohio-based artist Carmen Winant does in much of her work, and the same is true of her palm-sized paperback Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now (SPBH Editions, London, 2021). Winant explains that “‘instructional photography’ is a term that I have made up” to refer to photographs used to show people how to do things. My Googling finds the term in occasional use but referring to situations where what people are being shown how to do is photography. And maybe that reflexive usage is tacitly in play in Winant’s work, too, which would seem to be an extension of the image critiques of Roland Barthes, John Berger and company. Winant rightly sees that, as Friedrich Schiller knew, the aesthetic is an education: “Don’t artists too believe we have something to ‘teach’ with and through our work, even if the strategy is more oblique or speaks through metaphor?” But the isolated image—especially but not only when, like those we encounter in Instructional Photography, they are small, mostly monochromatic and grainy; “weak,” as Hito Steyerl might say—teaches nothing by itself. It is mute, muter than mute, and needs words and sequencing to lend it voice.

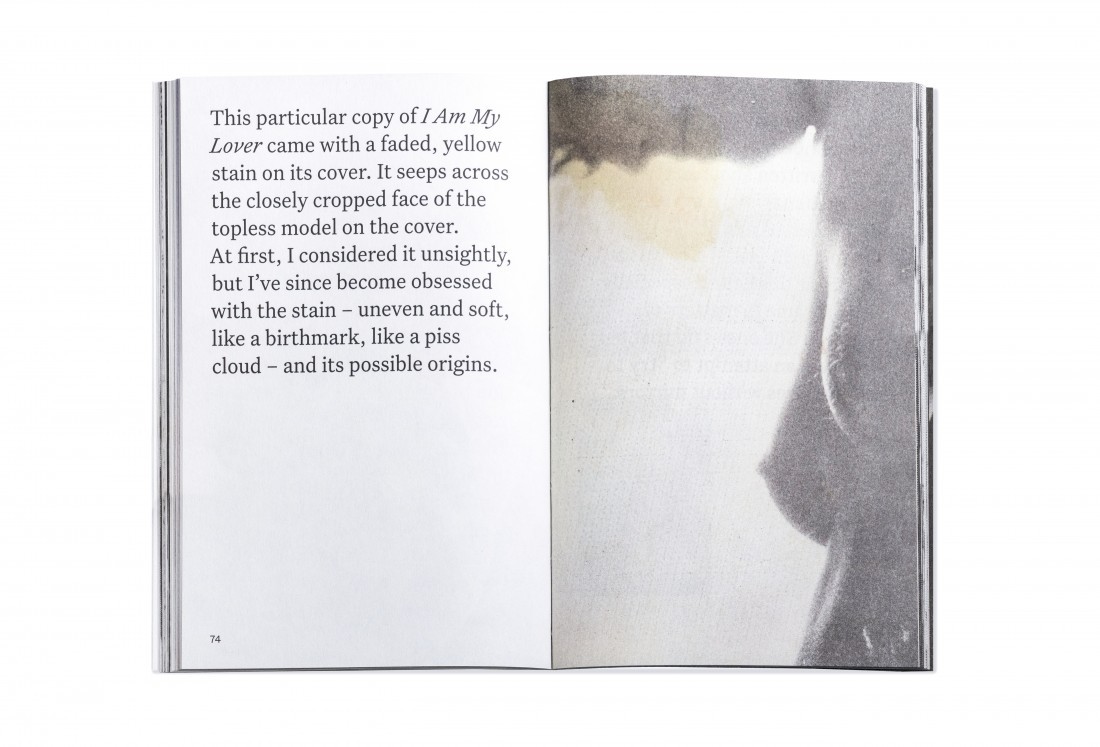

The images Winant has used may come, as she says, “from books on dog training, breast examination, meditation, bereavement, sex, and childcare,” but your dog won’t behave, your breasts won’t stay healthy, your spiritual state won’t be equilibrated, your mourning won’t lead to acceptance, your lovemaking won’t result in ecstasy and your children won’t thrive just thanks to anything you’ll see in these pictures. But you might learn something about looking, and about your own part in lending meaning to what you see—and in questioning that meaning. What happens when you look twice? Several of the pictures were taken from I Am My Lover, a book published in 1978, teaching women how to masturbate; among them is one that turns out to be from the book’s cover, and Winant’s accompanying text explains, “This particular copy … came with a faded, yellow stain on its cover. … At first, I considered it unsightly, but I’ve since become obsessed with the stain—uneven and soft, like a birthmark, like a piss cloud—and its possible origins.” And there’s the stain in the facing image, so faint one might have overlooked it, telling me that this seemingly black and white photograph is really a colour photograph, and that I wasn’t looking hard enough or sufficiently questioning what I was seeing. In the end, I am asked to invent: Winant writes of a picture in her archive whose model resembles herself. “Even my children misrecognize the subject as their mother.” What does the writer look like? Who knows? “I lost the image,” Winant says, “or I would reproduce it here.” The missing image might be the most poignant one in the book. And yet the intent, deeply focused appearance of the people in the photographs we do see retains a distinctive pathos. These men and women might as well be taking their instructions from the beyond.

Carmen Winant, Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now, published by SPBH Editions, 2021.

Carmen Winant, Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now, published by SPBH Editions, 2021.

Carmen Winant, Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now, published by SPBH Editions, 2021.

Daidō Moriyama, Random Walk, published by the[M] éditions, 2021.

Daidō Moriyama, Random Walk, published by the[M] éditions, 2021.

Daidō Moriyama, Random Walk, published by the[M] éditions, 2021.

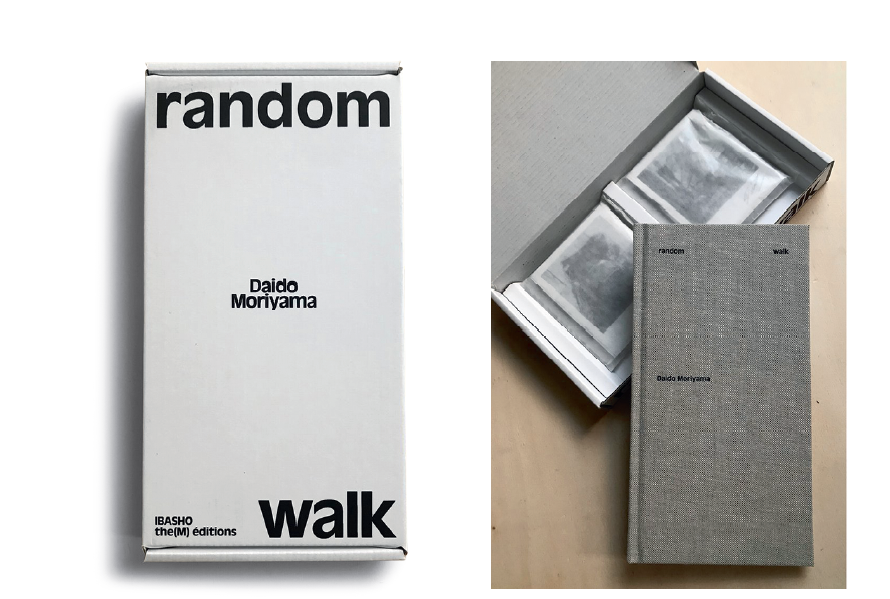

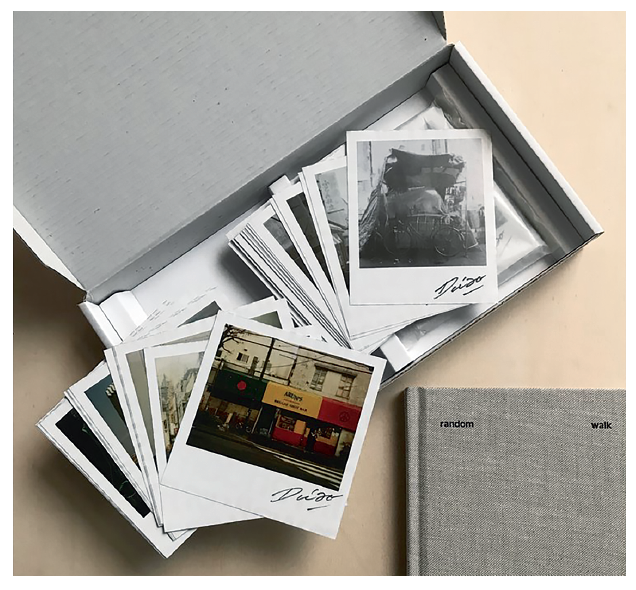

Not only can you make a photo book without making photographs, but if you do make them, you can make a book without putting the photos in it. Consider a recent work by Daidō Moriyama. Like a number of other Japanese photographers, he seems to be crazy for publications of all kinds, having issued nearly 200 of them since 1968. And in his 80s, he’s not slowing down: the Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation website, not quite up to date, shows 10 publications in 2020, 13 in 2019. Among his more recent efforts is Random Walk (the[M] éditions, Paris, and Ibasho, Antwerp, 2021, edition of 1,000), a sort of deconstructed or do-it-yourself book. Inside its cardboard box you find a tall, slim, clothbound book with black pages and two packs of stickerized Polaroid photos, 100 in all—62 black and white and 30 colour; the owner is invited to place the images in the book in any order to create a “random walk” through the city of Tokyo (though, in some of the colour pictures, you become privy to intimate moments that are unlikely to be found at random). In a brief foreword, printed in silver on the black paper, Moriyama explains his differing affections for the two kinds of image: “there is something ‘dreamy’ about black and white, and … I appreciate its ‘symbolically abstract’ quality,” which generates what he calls “the image and impact of an ‘alien’ scenery.” The colour photograph, too, he says, transports him to “an ‘alien world’” but through its hyperreality, its capacity “to make copies of the real world.” The funny thing is that, for me, at least in Moriyama’s work, it’s the colour images that seem dreamier, the black and white more imbued with the grainy texture of reality. But maybe it doesn’t matter, since in any case the point of both kinds of picture is to glimpse the elsewhere in the here.

Admirers of Moriyama’s moody, disenchanted vision will delight in this guided-unguided tour, but how many will really make their own book out of it? I suspect more will do as I intend to, keep the images loose in their wax paper packets, the better to enjoy them as simultaneously tactile and visual things, as well as to be able to rearrange them endlessly, keeping their randomness in perpetual play and preserving the instability consonant with their dreamy otherness. In that way, Random Walk turns out to be a book against books. Or anyway, it advocates a kind of lessness in the making of them.

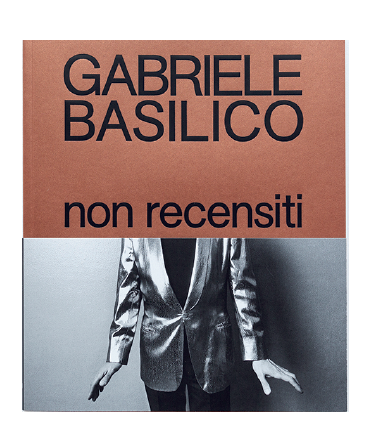

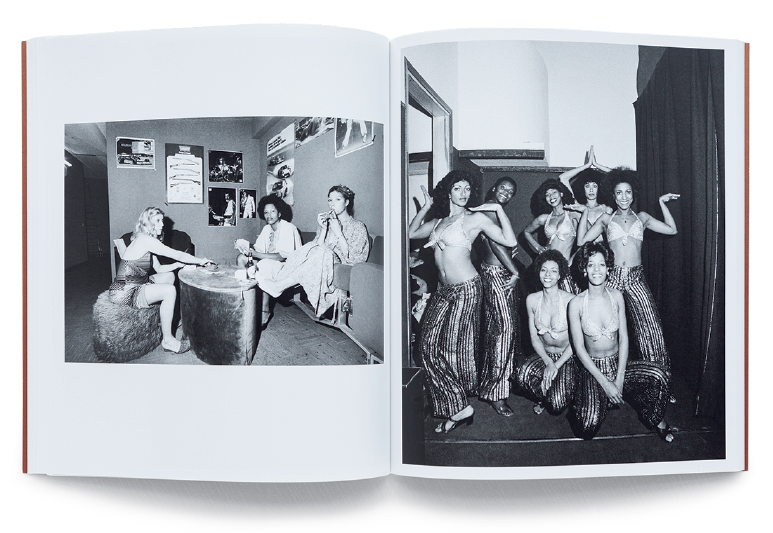

One way to bring lessness to the making of books is to just never get around to it. Apparently that was the fate of the material that ended up in Gabriele Basilico’s book non recensiti, finally published 40 years after he conceived it and eight years after his death in 2013 (Humboldt Books, Milan, 2021). Perhaps it’s not surprising that Basilico, best known as a practitioner of architectural photography, a “measurer of space,” did not quite know what to do with the black and white photographs he began taking in strip clubs and variety theatres in Rimini and Milan in 1976. He prepared a dummy of the proposed book, but nothing came of it, and the materials disappeared, resurfacing only in 2020. Finally published, it comes with texts by Giovanna Calvenzi and trickster-photographer Joan Fontcuberta—the latter an imaginary dialogue between Basilico and a photographer of Fontcuberta’s invention. Basilico’s lost book turns out to be a tender, slyly humorous immersion in a milieu that seems almost irreconcilable with the unpeopled cityscapes of quasimetaphysical stillness for which he became famous. Still, Basilico is a measurer of space here, too; you always feel the walls and curtains that impinge on the figures, bracketing out any external reality. These backstage portraits of strippers, clowns and strongmen but also prop makers, a dance instructor and other normally unseen denizens of this parallel world invite the viewers’ complicity, suggesting that we, too, could easily become members of their magical, semi-secret family. In the end, though, the illusion is foreclosed, and the final image is of a venue with the gate pulled down and the sign CHIUSO PER VENERDI SANTO, closed for Good Friday. Too bad; there are some performers on the bill I would have liked to see—and can only wonder, for example, at what the act of Emily Proust might have been.

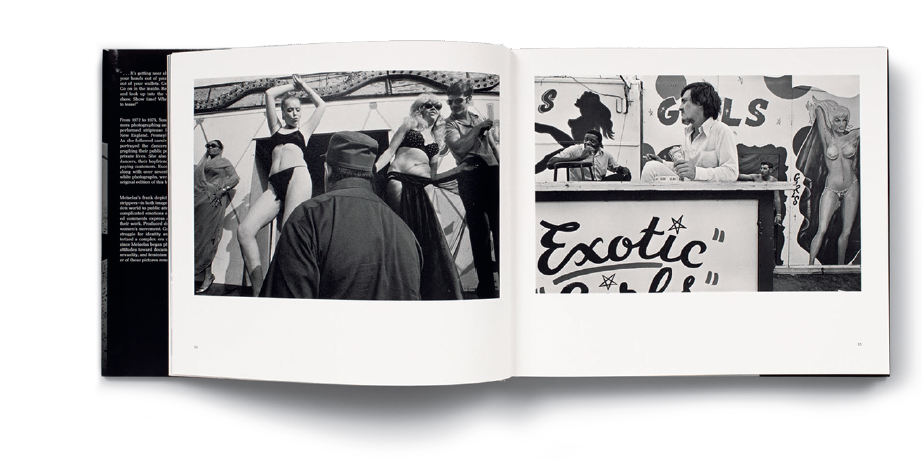

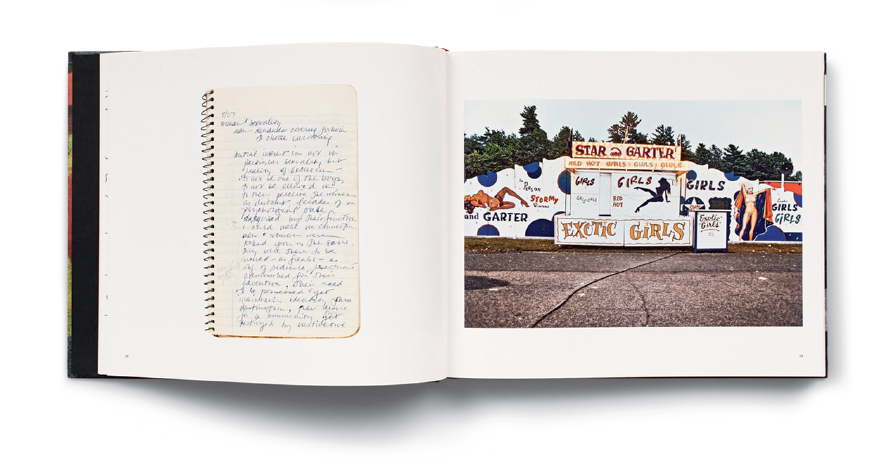

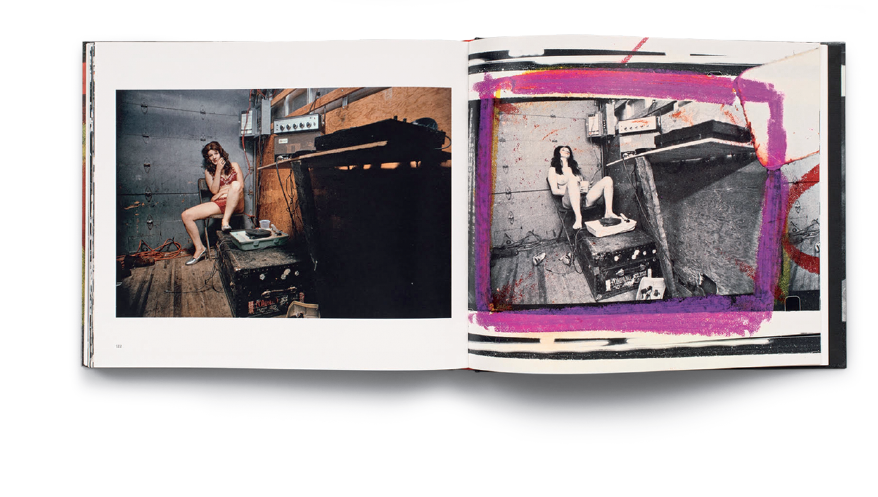

A similar milieu comes to life in Susan Meiselas’s classic photobook from 1976, Carnival Strippers. Far from a lost book like Basilico’s, it’s one that has expanded with time. It has recently been republished in a third edition (Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, 2021) and, along with Meiselas’s original imagery and texts (mostly excerpts from interviews with the book’s subjects), it includes Sylvia Wolf’s essay for the 2003 revised edition, as well as a new essay by Abigail Solomon-Godeau. More significantly, it is now boxed with a companion Making Of volume comprising contact sheets, individual images (including many in colour—those in the published book are all black and white) and typed and handwritten texts. It’s all proof positive (if needed) that even the most perfectly crafted book is just one instance of a multitude, perhaps an infinity of possible versions of itself—and that each of those possible versions implies a different version of the relation between its maker and herself as well as between its maker and her world. “Every choice becomes an act to recover and reveal oneself alongside others,” as Meiselas reflects in the present. But her 1976 self dwelt on something else: “Any book allows its reader to distance himself.” I won’t make too much of the conventional linguistic usage of the day, according to which the reader was generically male; what strikes me more is that “reader” here encompasses the book’s maker—and, in a different way, its subject-participants, too. Distancing yourself turns out to be an essential activity for living. In her minute focus on the nitty-gritty working-class work of the stripper, Meiselas exposes so much about the work of anyone who trades in appearances, whose work is to slip uneasily between fiction and reality (but also power and vulnerability)—which might be anyone but is certainly any artist. Maybe that’s what gave Meiselas the nonetheless-unsparing empathy that allowed her to manifest these raw and centrifugal images; even the portraits, seemingly more straightforward or even static, evince subtle formal torsions that undermine their overt balance and prod us to question our stance toward the subject.

Gabriele Basilico, non recensiti, published by Humboldt Books, 2021.

Gabriele Basilico, non recensiti, published by Humboldt Books, 2021.

Gabriele Basilico, non recensiti, published by Humboldt Books, 2021.

Gabriele Basilico, non recensiti, published by Humboldt Books, 2021.

Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers, published by Steidl, 2021.

Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers, published by Steidl, 2021.

Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers, published by Steidl, 2021.

Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers, published by Steidl, 2021.

Fontcuberta gives his imagined Basilico the thought that “the precarity and obsolescence of these coarse but honest venues, tacky but full of vitality, fills me with nostalgia.” How could it be otherwise? From today’s perspective, and longer than that in fact, what Basilico documented in non recensiti and Meiselas recorded in Carnival Strippers are lost worlds, at once terribly ordinary and barely known. And every lost world, however tawdry, however grim, might be a lost paradise. Or at least less depressing than the present. Am I wrong to feel that the trashy commercialized sexuality of nearly 50 years ago, as exemplified by the travelling strip shows Meiselas followed through rural New England, or by the nightclubs in decline and “frequented largely by soldiers on leave and old-age pensioners” that Calvenzi describes as Basilico’s haunts, was somehow less squalid and more forgiving of true feeling than the polished and airbrushed version peddled today by the Internet? Or is it just distance, or rather distancing, that makes it seem so? ❚

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition “Jeff Wall” (Potomac, Maryland: Glenstone Museum, 2021). His new collection of poetry is Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022).