Notes on Fuseology

Carolee Schneeman Remembers James Tenney

The painter, performance artist and filmmaker Carolee Schneemann met composer James Tenney in New York in 1955 and they maintained contact with one another until his death in 2006. Their relationship was especially intense in the mid-’60s, during which time they collaborated in a number of ways; in Fuses their lovemaking formed the core of a film that remains an enduring expression of both art and love; Tenney created the sound collages for Viet Flakes, 1965, and Snows, 1970, and performed in the New York production of Meat Joy, 1964, Schneemann’s orgiastic celebration of the expressive body.

James Tenney emerged as one of America’s most important composers and a number of his pieces will be performed at the New Music Festival in Winnipeg in 2015. The following interview with Carolee Schneemann about her life and work with James Tenney was conducted by telephone from Toronto to Springtown, New York on October 25, 2014. Ms Schneemann had just returned from Texas where she had received the prestigious Aurora Award for 2014. The award is given to an artist who demonstrates “extraordinary originality in the field of moving image art.”

Carolee Schneemann and James Tenney, March 1961. Image courtesy Carolee Schneemann

BORDER CROSSINGS: The dedication to “Split Decision,” your two-city exhibition in 2007, was to James Tenney. What occasioned a tribute to him 40 years after you had been together? CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN: Our continuing affinity and the rarity and the specialness of that relationship. As time has gone on, I see how remarkable it really was. It was urgent, coherent, mutually influential and inspiring. It was altogether wonderful.

There is a picture of the two of you taken in 1955. You’re both adorable but you look like kids. We absolutely were kids. We met through a set of magic coincidences. He was on a fellowship and he lived in a tiny little closet of a room for graduate students. He was going down to the Thalia Theater to see a movie and on the bus he suddenly hallucinated this girl’s face, huge, like the Cheshire cat, and he missed his stop. So instead he came to a concert on 57th Street at Judson Hall. I had gone there to hear Charles Ives and Bach; I wanted so much to hear the Bach and I didn’t know anything about Ives. It was the 19th of May, a mystical day for me, and I knew I had to do something special. I was on leave from Bard and I had a year to live in the city. So suddenly this skinny guy who I had seen three times in a little café near Columbia came in. I had seen him eating out of a bowl and he did it with the intensity of a tiger. He had a different energy that I would come to understand was western—he was born in New Mexico, grew up in Colorado—and his presence was unique. He walked in late for the concert, which I thought was odd, because he was very shy. He sat down and then just as the pianist was coming in, he stood up, changed to the aisle, and ended up sitting opposite to me. Then at intermission I had to figure out how we could meet. Finally I went over and said, “I’ve seen you at the café” and he said, “Yes, I remember you,” and I said, “I’m a painting student at Columbia” and he said, “I’m a musician at Julliard,” and then I said something like, “That’s so interesting, I’m thinking of painting as space becoming time,” and he said, “And I’m doing my music so that time is becoming space.” We were half joking but that’s what we told one another. We laid out that affinity immediately.

What kind of a conception did you have as a painter at the time? I was very fierce. I’d been told from the earliest times that it was pointless and that I should stop. At Bard my best painting professor said, “Don’t set your heart on art, you’re only a girl.” That was what it was like, so it was quite unusual to have a companion and lover who was so equitable, the way Jim was.

Carolee Schneemann, James Tenney and Kitsch.

In 1958 you painted a rather remarkable portrait of Tenney that looks like Oskar Kokoschka meets Henri Matisse. Kitch, the cat, is in the portrait as is an elegant coffee pot. What were you trying to capture in that portrait? I simply wanted to have Jim’s presence in a painting. It was full of the dailyness, the intimacy and the constancy of our work. I was listening to Ives, chords, fragments, broken phrases over and over again and that was very important for how I was thinking about pictorial space. I wanted to increase fracture, I didn’t know quite how that would work, but I knew there was something incremental in collage and in the breaking of form. As an 11-year-old kid I had wandered into a classroom in the basement of the Philadelphia Museum of Art where there were grown-ups painting still life. The teacher let me come in and he took somebody’s lunch bag and tore it up into hundreds of tiny pieces and dropped them on the floor in front of us. Then he asked the grown-ups, “Why have I torn up this paper bag and what do you see?” No one moved a muscle, so I said, “Is it because of the rhythm between the pieces?” and the teacher was thrilled and said, “Yes, it’s Gestalt.” So I learned a big German word and a concept that would always be influential. In Meta (+) Hodos, Tenney wrote a very intense and cohesive analytic essay on Gestalt. That was how we wove through each other’s sensibilities.

So there was a crossing over? Your practices were beginning to intersect and you were interested in the spatial qualities of sound? Yes, and listening to how he constructed sound in space. That was daily for us. He was practising Ives and Webern and I was painting in the next room and it was full of the aroma and the energy of what was going on between us.

Leon Golub and Nancy Spero had the same kind of intense aesthetic relationship. But in your case it was the sound of his world that you translated into visual space. Unlike Nancy and Leon we rarely argued. But there were many influences: from certain thresholds in poetry to Stan Brakhage, Jim’s best friend from Colorado, who brought us to film. Then, through some of Jim’s associates in New York I was taken into what became the Judson Dance group and began to choreograph with them. And Cage and Cunningham became friends and attended everything that Jim and I made. It was like an electrical nest with everything connecting.

What was Tenney’s interest in visual art and in performance? Did he have a sense from the start that his interests would drift towards the visual world? Not necessarily. Of course, he had the experience of participating in Brakhage’s earliest films so there was that visuality. For me, Stan’s earliest films were all black and white psychodramas.

You were reading Wilhelm Reich and D’Arcy Thompson, a biologist who developed ideas of organic form. We were doing research on biology and organic form and then Jim went into complex theories of sound through Erwin Schrödinger. We were reading Freud, Proust and Rilke. The Second Sex had come out and we also had a passionate interest in de Beauvoir. It was a great range of influences that I would relate to Charles Olson’s sense of deep space. There was always some opening, some deepening aspect of what the research brought us. Reich did make an impression particularly because of the militaristic government that we had. His analysis of sexual oppression and fascism was especially helpful to us.

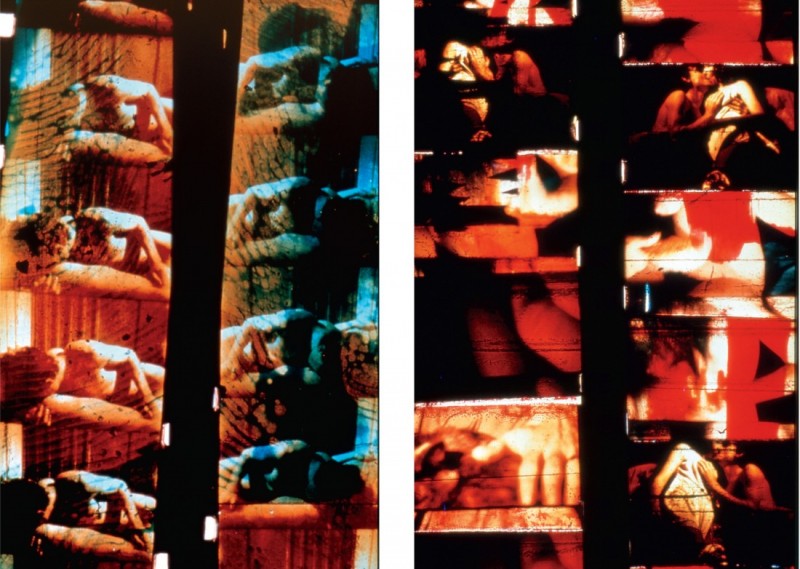

Fuses, 1967, 16-mm colour film, silent, 18 min.

Is Fuses the first time that you and Tenney performed together? Although that might be a more calculated word than I think it must have been. Please don’t use the word perform. Fuses was the first collaborative visual work. He wanted us to do it. It has no soundtrack. There was a previous little work, shot on 8mm, titled Carl Ruggles’ Christmas Breakfast from 1963 that had their recorded conversations. Viet Flakes was our first sound collaboration, then Meat Joy and Snows. Then we created a duet, Noise Bodies, in 1965. That whole installation is going to an exhibition of Charlotte Moorman’s history at the Block Museum of Art next year, so I had to dig up all the noise-making elements. I found them, they were all covered in mouse poop but they are okay.

You wore what you called sound-producing debris for that piece? Did the soundscape come out of a kinetic assemblage? Right. It was a noisy collage. We improvised together regarding what made sound and what gestures would produce varieties of sound. The way my kinetic theatre pieces developed was that parameters were set in terms of certain kinds of duration, position and action and then from studying those we would improvise. So each performance was different. Meat Joy has a score and units of specific active improvisation, and then within that motions change and are fluid.

Did Tenney share your rage at the Vietnam War? Are you kidding? He wanted me to cut his back with a razor and I couldn’t do it. The pain his body endured would be his way of accepting and sharing what the Vietnamese were going through.

In Viet Flakes, did you assemble the images and then did Tenney overlay the sound collage and the audio fragments? We worked together side by side. I chose the sound and then he added his thoughts to the sound material. We constructed the sounds so the rhythms related to the energy of the atrocity images.

The pop songs work in a weird way. It’s strange to hear lines like, “we can work it out” and “all you need is love” over the atrocity images we’re seeing. We wanted something grating and contradictory, and to put the paradox of our normal sound environment against the militaristic insanity of the war. Jim found the sources for the Vietnamese chants, which were essential to the sound structure. My work is an experiment and I never know if I’m going to realize the potential of this other voice. The gift is that it has been sustaining and that the work can carry an intense emotional weight.

Over what period of time was Fuses filmed? A year or two. Funnily enough, I’m in my same bedroom right now where I filmed it, and I can see the ceiling fixture where I hung the Bolex, wound it up, and then jumped into bed. I can see the pot-bellied stove where I balanced it. And with a Bolex you only get 30 seconds of film, so that determined the collage nature of the film and also the risk and uncertainty. I like that and I need that. I couldn’t work from a specific, programmatic score.

Isn’t constructing a film with only 30-second intervals a bit awkward? It is but I like those constraints. They occur in all my work in some way, partly because I never have quite the right equipment, or the right lighting, or the right weather. But when we were making Fuses I’d be doing the dishes and I’d turn to Jim and say, “Look the light is so beautiful, I wish we could just go back to bed,” and he would say, “Okay, I’ll get the Bolex.”

Meat Joy, 1964, performance: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, plastic, rope. Photo: Al Giese.

And you could always count on Kitch to be the onlooker with the penetrating gaze. She was the aesthetic permission. I always thought of her as the camera director. If you had someone in your intimate space, it was going to be Kitch.

You never had any qualms about using your bodies in Fuses? No, because I needed to see if I could re-proportion the structures that were being given to me as hierarchical aesthetic factors. Pop art produced mechanized female bodies and I wanted to show something different from that deadness and slickness. It was in the culture as a way of being and looking and behaving. We refused to let our bodies become instruments of that kind of power. What we were doing wasn’t something we had to fight for, or go into Reichian analysis for. We had our innate pleasurable bodies and expressivities.

It’s interesting to hear you say that you never had the right equipment because in Snows you work very early on with the group Experiments in Art & Technology. The way that you’re using contact microphones and having the audience be a generator of the action was a progressive way of making a performance at the time. Was that because of the engineers at EAT or was that Tenney’s influence? Jim was working at Bell Labs and that made access possible for me. Snows has never been appropriately appreciated for its technology; it has always been more like, “Look what the crazy girl did.” The structure and the layers of technology were the things that helped make the piece so powerful, but you and I are speaking about it in a way that has rarely been done.

You turned the whole theatre into a kind of feedback instrument. Did you know what you were going to get out of this process? Well, I knew what I wanted. I always envision what is possible, and then how to get it—that’s the adventure. It was a beginning of an intensive transformation of the space into an active sounding space and it worked.

Did Tenney view the sound component in the same democratic and integral way that you did? Yes. He enhanced where I had to go with the concept. He usually had the technical experience that could stabilize what I needed to have happen.

Interestingly, Tenney worked in a more structured way with algorithms, and your approach seemed to be more spontaneous. Was that balance useful to the two of you in your collaboration? The materiality of what concerned us was relatively specific and equal. Listen to this quote from Meta+Hodos: “We know from our visual experience that a change in scale of a picture of a thing, or a change in the distance from which we view a thing, whether it be a picture or a landscape or a figure can substantially alter the total impression we will have of it. The overall gestalt character of a thing seen is to a great extent determined or conditioned by the scale on which we view it.” This is painter talk taken to a high degree of theoretical construct. I would say that was the kind of fluidity that we had.

You say you never had domestic fights. But did you have disagreements about the way that he might want to use sound in your pieces? No. We had agreements on how to facilitate them. A lot of his work was done on equipment we had in the house. It was in the environment and the discussions were constant. Whatever we were researching would become an area of discussion. Then one of us would take or intensify information from the other and use it. It was all very fluid.

Viet Flakes, 1965, 16-mm toned black and white film, sound collage by James Tenney.

His desperate need for you is apparent from the letters he is sending while you’re performing Meat Joy in Paris. They are full of physical longing, as are yours back to him. Being apart was clearly a difficult thing for both of you. It was excruciating. We had a very specific closeness.

He writes saying he can’t even compose because he misses you so much. We needed that life energy for us to really be working. I was miserable without him when we were performing Meat Joy in Paris but I felt that the work was another aspect of tribute to our life together. That was how I thought of it. He insisted on being in Meat Joy when we did it in New York. I didn’t want him in it because I thought I needed some distance to shape these participants, but it ended up being perfect.

There is a moment in “Grabs and Falls,” a section in Snows, when he is circling a woman and he is genuinely menacing. We practised the menace. It came naturally within the structure of the work but for all the participants “Grabs and Falls” takes a lot of training. That kind of jockeying before you attack was based on watching two cats.

Your relationship with Tenney begins with the Cheshire smile and continues on with a cat playing a major role. The cat, Kitsch, was exceptional.

One of the things your letters trace after you separate is that the love remains. It even seems to intensify. It was very, very deep. When he was teaching in Toronto he got lung cancer and while he was in hospital his young wife developed a back ache, went into hospital and died there of advanced ovarian cancer. Jim survived with one lung and two babies, a two-year old and a four-year old. So he gets a car with baby seats so that he can come back to the States to see me, Stan and others. I asked my dear friend, Lauren Pratt, to help me throw a party for him in New York, which we do, and all his friends come to this loft—Jonas Mekas, Yvonne Rainer, Stan and Pauline Oliveros are all there. But when Jim arrives he and Lauren look at one another and they’re like crazy cats. The two of them end up making love on the couch and they fall in love. And she says, “What am I going to do, my mother is very upset that I’m going to be with a musician who has one lung and two children.” I said, “Go for it.” They marry, have a loving domestic life, a wonderful son and raise his two children. When the cancer returns in 1989 Jim is so sick, and I am invited to stay with them in California. It was extraordinary. One day he was writing a major opus and suffering from the cancer treatment and he said, “The two of you take every work in this house by Carolee and get them framed properly, now.” He wanted Lauren and me to do it together.

From your perspective what was the most important thing he brought to your collaboration? His full heart. He had great energy and he was magical. ❚