Mira Schendel

This is unquestionably an important exhibition, showcasing as it does the full range of Mira Schendel’s delicate, sensitive, questing and prolific oeuvre through 14 rooms and 270 works. But does it, as curator Tanya Barson claims, amount to “an experimental investigation into profound philosophical questions concerning existence, belief and our position in relation to the world?” It’s obvious enough that philosophers can apply their skills to the understanding of art—as did the late Arthur Danto—or help to make it, witness Thomas Hirschhorn’s close collaboration with Marcus Steinweg. Artists, equally, can be influenced by philosophy. But can they meaningfully use philosophical concepts in ways which amount to ‘doing philosophy’ by visual means?

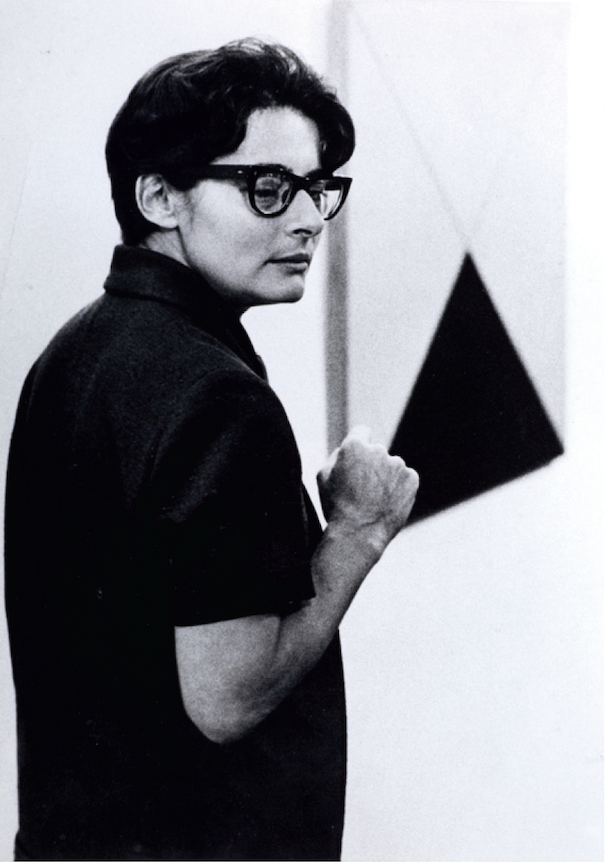

Mira Schendel, courtesy Mira Schendel Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photograph: Mira Schendel Archive.

Schendel’s work enters this potential zone around about 1964. Before that, she painted muted and plangent still lifes, channelling Morandi and Klee and ending up not so far from British painter William Scott. From there, her late ’50s and early ’60s paintings moved in architectural and then simplified geometrical directions, but always with a warm surface materiality which humanizes what might otherwise seem austere.

Schendel’s philosophical turn feeds into a wide variety of work, including hanging discs perforated by hundreds of holes to celestial effect; a whole-room installation of barely visible thread; and many notebooks, which are beautifully shown as both objects and as explorable video reproductions. But rice paper, palpably precarious in its presence, emerges as her essential medium. Schendel used it to make sculptures which foreground fragility and imply transcience; the Droghuinhas (Little Nothings) do no more than screw up and knot the paper; and even less is done to the sheets hung as if on a washing line, which her young daughter gave the apposite title Trenzinhos (Little Trains). As Jorge Guinle suggested (as quoted in the catalogue from an early interview with Schendel) the work becomes tenuous enough to “blur the border between being and non-being.”

Mira Schendel, Untitled (from the series “Spray”), ca. 1975–76, spray paint and ecoline watercolour on paper, 52 x 26.5 cm. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photograph: Genevieve Hanson.

Yet one senses that the drawings and monotypes, hung between sheets of acetate so that both sides of semi-transparent paper are in play, are at the core of Schendel’s concerns. Their “metaphysical calligraphy,” in artist David Medalla’s phrase, is decidedly beautiful, especially in the two multi-panelled installations Graphic Objects (black writing on 14 suspended panels, recreated as shown in the 1968 Venice Biennale) and Variants, 1977 (near-white oil on white). The aesthetic of scratching—often with a fingernail—into inked paper generates personal mark-making beneath the cover of an apparent attempt to approach the objectivity of type. Letters take off as subjects in themselves—Schendel has a particular way with marching L’s and dancing A’s.

Schendel was actively involved in São Paulo—and, by correspondence, international—intellectual circles. That meant more to her than any grouping of artists, and she often includes phrases from such philosophical sources as the Czech Vilém Flusser and the Germans Jean Gebser and Max Bense. But any attempt to literally read Schendel’s monotypes is problematic; the words, spread across several languages, dance and pose more than they signify. So, though there may be philosophy in the mix, the effect is to evoke philosophical thought, to gesture at it, not to carry it out. We are teased with the ungraspable, or with the potentiality, not the realization of meaning. Flusser’s description gets to the heart of it: “her ephemeral and vulnerable strips of rice paper are covered with lines and footprints impressed on the snow of immanence.”

That sense of immanence, of finding the spiritual within the everyday world, connects with the concept which provides the visual logic for the monotypes: that of transparency, which Schendel took from Gebser. He developed a theory whereby past, present and future were linked through an evolution of consciousness which enabled the spiritual to become transparently visible in the most advanced—integrated—form of consciousness, one which goes beyond the rationalist and logic-driven paradigms of technological capitalism to see through to our pre-linguistic origins. I can’t see how Schendel’s work can be said to investigate, rather than merely illustrate, such abstruse matters, but they do fit with the monotypes facing both ways to make a central presence which is hard to grasp, and which in some sense has no background; in formal terms, the whole question of the figure/ground relationship is done away with. I found myself thinking, though it’s probably nothing to do with Gebser, that the monotypes might merely suggest that all will be open, that the meaning of the world will be transparent to us, while at the same time the illegible blizzard of different languages, blurrings, reversals and overlays shows that promise to be an illusion.

That’s the point at which Schendel’s own fractured and emotionally, geographically and religiously unsettled life might suggest an autobiographical reading. Jewish, but brought up as a Catholic, she was born in Zurich then lived in Milan and Rome before anti-Semitism drove her to Yugoslavia during the war. She left for Brazil in 1949, aged 30, and settled in São Paolo from 1953. There, Schendel engaged with Eastern thought, and often used the chance procedures of the I Ching to make decisions. Her primary languages were Italian, German and Portuguese, but she was said to speak them all with a foreign accent. No wonder hers is an art of shifting states.

Mira Schendel, Ondas paradas de probabilidade (Still waves of probability), 1969, nylon thread and wall text on acrylic sheet, installation view “Mira Schendel,” 2014. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Photograph: Genevieve Hanson.

Whether or not Schendel’s influence is at play, her way of undermining the would-be clarity of verbal meaning matches a decidedly current tendency: the visual artist’s use of language—the medium of communication—to frustrate that purpose, often as a means of criticizing how its power relations play out in conventional use. That has some resonance with the way demands for transparency have become something of a moral slogan, suggesting that power will be spread wider if everything is visible. At the same time problems are recognized—that transparency cuts both ways, with surveillance its dark side; and that sheer volume—taking the internet as the obvious case—has its own way of disempowering. Such considerations seem entirely germane to Schendel’s art; she presents the possibility of seeing through to the meaning behind things, but doesn’t deliver it. “The back of transparency lies in front of you,” she wrote, “and the ‘other world’ turns out to be this one.”

Schendel, then, achieves sincerity, authenticity and a sense of the fragility of all things in the face of history. I don’t see her as demonstrating philosophical thinking so much as being haunted by philosophy, paralleling a sense of being haunted by the past. It’s that dual haunting which gives the work its emotional power, and that emotional power which sets Schendel aside from less engaged forms of minimalism. Was Schendel herself aiming at more, at “an experimental investigation into profound philosophical questions?” Perhaps so, but it need not be a problem if something isn’t what it sets out to be. Indeed, there may be a little philosophy of life to be gleaned from that. ❚

“Mira Schendel” was exhibited at Tate Modern, London, UK, from September 25, 2013 to January 19, 2014.

Paul Carey-Kent is a freelance art critic in Southhampton, England, whose writings can be found at <paulsartworld.blogspot.ca>.