Michael Snow

Surveying the artist’s use of still photography in works dating from 1962 through 2003, “Michael Snow: Photo-Centric” provided at once a revealing cross section through his multifarious oeuvre and an overview of possible approaches to the photograph in the era bracketed by the gradual dissolution of modernist understandings of “medium” on one side and the digital revolution on the other. But what comes across most strongly, perhaps, is that Snow’s exploratory attitude is ultimately more salient than whatever he happens to be exploring at any given moment. Photography for him is not so much a medium in the modernist sense—that by virtue of which, as Clement Greenberg supposed, “each art is unique and strictly itself”—as, more simply, a means, that is, way of going about doing things; and sometimes a material, that is, the stuff to which things are done.

The attitude that emerges from all this work is distinctly workaday, almost homespun. Snow never makes a drama of his relation to the camera, the profilmic scene, its lighting, the photographic print, the sequence or arrangement of display, or any other aspect of his photographic practice. Rather, he is curious to see what can come of them. Just as painting, drawing, sculpture, film exist not simply to transcribe what we see but to make us see otherwise, photographic practices generate unexpected effects and Snow wants to know what these are, neither to critique them nor to instrumentalize them, but to observe and enjoy them. Snow’s first “photo-work,” by his own account, is Four to Five, 1962. From one point of view it could be considered the mere documentation of a series of actions: placing a black cut-out “walking woman” figure in various urban settings—a subway station, the street. But in fact, what the images document is not so much the presence of the cut-outs in the scenes where Snow had placed them but the fact that this fragment of fiction serves by its presence to block or disrupt the viewer’s perception of the “real” and thereby to elicit, in a witty but somewhat disquieting manner, an awareness of the strangeness, the distraction, the unreality of our mundane reality.

More than 40 years later, Snow inverted this operation in Paris de jugement Le and/or State of the Arts, 2003; instead of interposing a fictive woman between the camera and reality, interposing real women in front of fictive ones. This single-image work is a colour photograph of three nude young women standing in front of the Philadelphia Museum’s own great Large Bathers, 1906–1909, by Cézanne. The women, who appear to be standing so close to the canvas that they can hardly be thought of as looking at it—theirs would be more like what Marcel Duchamp might have called an “olfactory” relation to the painting—block our view of most of its lower half, throwing their shadows on it as well, but we can still glimpse some of Cézanne’s own poignantly ungainly nudes at the extreme right and left of the image. According to the curator, “the viewer is asked to ponder which of the two mediums”—photography or painting—“wins in the struggle for representation,” but I see it differently: It is the three models who are the judges, however true it may be that some viewers will take them as merely objects of scrutiny and not above all the ones who exercise it.

My citation of these two works—early and relatively recent—from among some 30 marvelously varied pieces is meant to evoke, however tentatively, a somewhat overlooked aspect of Snow’s art: However rigorously structural it has been and remains, however much it eschews anecdote and literary metaphor in order to cultivate the transformative potential of the (in this case) photographic apparatus itself, there is always some remainder of unstructured and uncontainable desire or subjectivity in play. What remains incompletely assimilable to the work’s structuring is the figure of Woman. The deployment of the female figure in both Four to Five and Paris de jugement Le can and should be seen as implicitly feminist—the woman who strides fearlessly through public space, who exercises judgment over even the most culturally exalted artistic representations of women—but is still also at the service of a specifically male delectation.

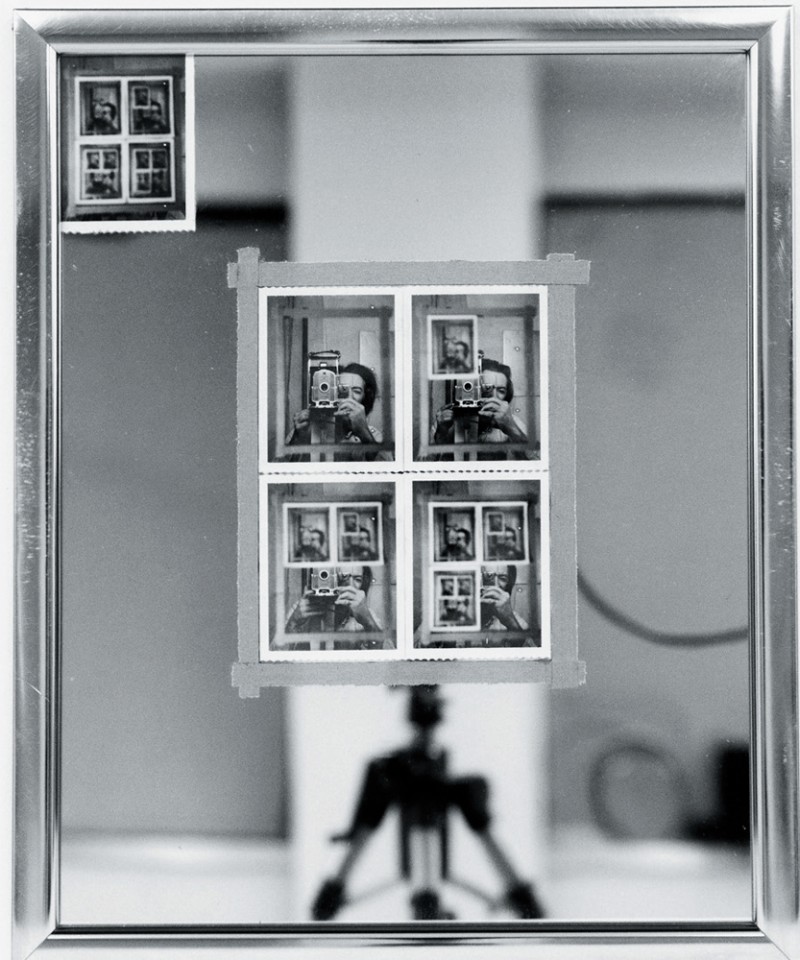

It’s extraordinary that the artist can represent himself without dealing in autobiography or, in any traditional sense, self-portraiture; a work in which Snow’s own likeness appears is not therefore ‘about’ himself in person, except ‘for example;’ thus, in Authorization, 1969, he appears as an example of anyone who might operate a camera. It is, as curator Adelina Vlas says, “a record of its own creation,” and the photographer is figured merely as one more element in that process, just as the viewer is finally added by way of the mirror (like the one used in the making of the image) on which the print has been affixed—just any viewer, as such. But when the female figure appears in Snow’s work, by contrast, this careful neutrality is abrogated. The triptych Crouch, Leap and Land from 1970—hung parallel to the floor from the ceiling, at waist height, forcing the viewer to crouch down and look up in order to see them—may not be precisely comparable to Courbet’s L’Origine du monde, but with Land one sees something similar, and the undignified position the viewer has had to take is revealed as distinctly voyeuristic. As Vlas says, Snow’s work is about “embodied perception”—but she neglects to add that where there’s a body and its perception, there can always be some perversity. ❚

“Michael Snow: Photo-Centric” was exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, February 1 to April 17, 2014.

Barry Schwabsky’s most recent book is Words for Art: Criticism, History, Theory, Practice (Sternberg Press, Berlin) and his new collection of poems, Trembling Hand Equilibrium, is forthcoming from Black Square Editions, New York.