Mary Heilmann

It isn’t hard to characterize Mary Heilmann. She was born in 1940 and for 45 years now she’s been investing simple abstract geometric motifs with personal feelings, a brightly coloured West Coast vibe and elements from popular and craft cultures—all to a generally sunny effect. Her inventiveness extends into making ceramics and constructing chairs to encourage visitors to relax and take their time. The question, approaching the Whitechapel Gallery, was whether that would be enough to sustain a major retrospective.

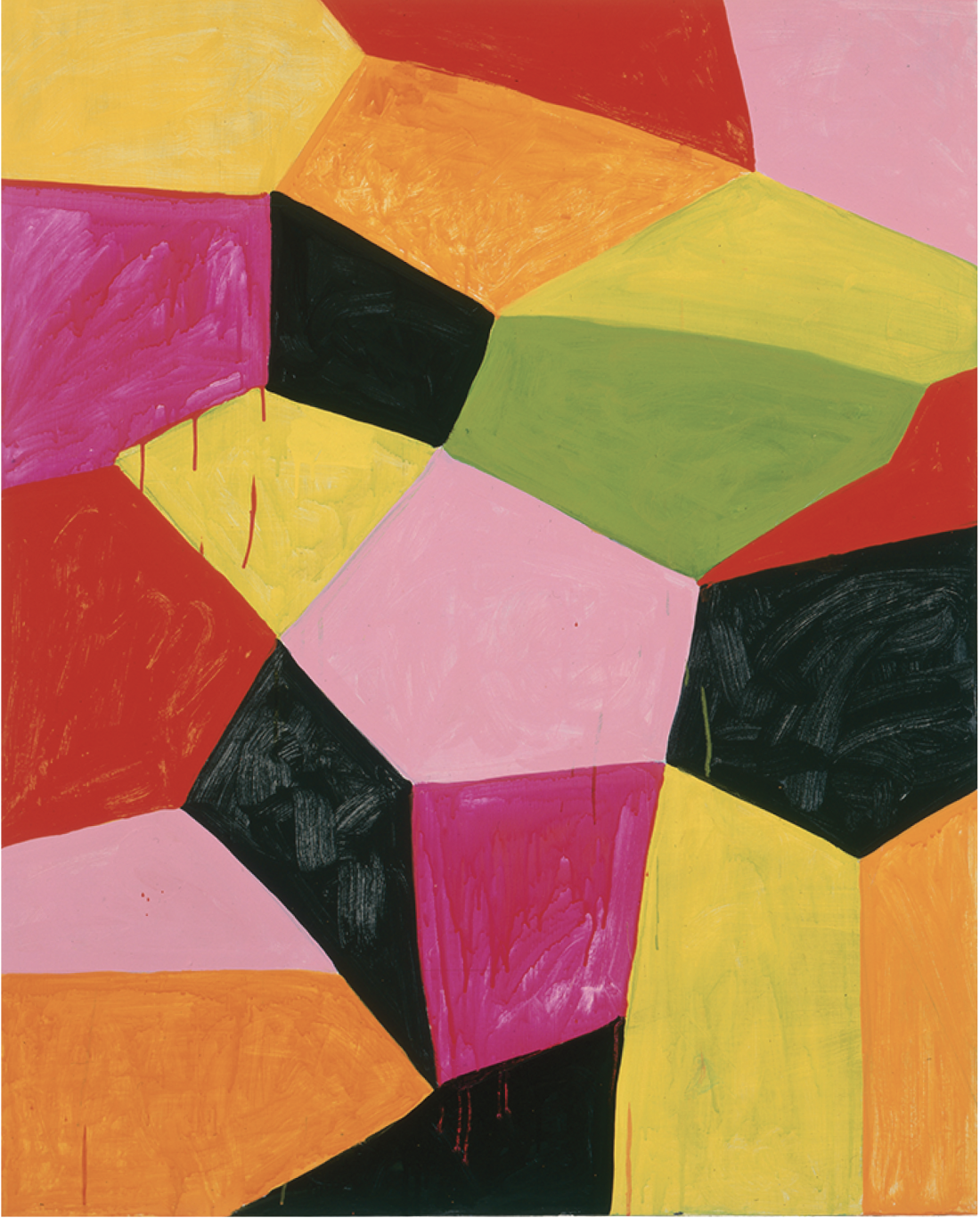

In a broadly chronological installation, we start in the early 1970s, when Heilmann moved with knowing provocativeness from a sculptural background and training towards then-unfashionable abstract painting. It was soon apparent that she enjoyed painting, and she rapidly alighted on using geometry as an underlying structure, but following it with a humanizing looseness—congruent with accepting that she’s more an outsider than a technical master. Sculptor-like, she always treats the painting as an object, for example, by painting the sides, often to significant effect. That’s made explicit in her use of ceramics, a group of which are presented on the wall and fit right in to the flow of paintings. The colours, though strong, were somewhat dirty at this stage, but soon emerged into Heilmann’s characteristic intensified pastel shades. The show’s text calls them “eye-popping,” but they never go as far as that implies—as far, say, as Peter Halley or Peter Saul—towards fluorescence or aggressive clashes. Moreover, there’s often a fair amount of black offsetting the bright hues.

Mary Heilmann, Taste of Honey, 2011, oil on canvas, 76.8 x 60.9 cm. © Mary Heilmann. Photograph: Thomas Müller. All images courtesy the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth.

Halfway through the exhibition there is the attractive 13-minute slide show Her Life, 2008. Paintings fade in and out along with the occasional photograph—sunsets, colourful grids of parked cars—to the sound of some of Heilmann’s favourite songs (this and a corridor arrangement of album covers from Heilmann’s own collection reinforces the importance of music to her). The show’s text says that Her Life confirms the centrality of autobiography, something which Heilmann, too, stresses. That may be so, but the photographs are more notational than personal, and though the grounding in the artist’s life matches the casual warmth of the paintings, it doesn’t operate in a way which allows the viewer to decode the experience, however long they sit on the chairs Heilmann has introduced for the purpose. Heilmann seems not so much to start with the world as to accept that the world will enter and to look back, after finishing a painting, to capture that in her titles. The results are mostly more evocative than representational; Ellsworth Kelly or Howard Hodgkin achieve some similarity of effect, but through a different route, given that they start with more particular objects (Kelly) or experiences (Hodgkin). Like them, Heilmann operates in different territory from an abstract expressionist or minimalist. So it is that the typical combination of painting and title doesn’t allow the viewer to work out what is being shown, nor to deduce Heilmann’s views on anything—though it does encourage speculation. Just as the physical process of Heilmann’s production is explicitly visible, the psychological drivers of her work remain invisible. Certainly they’re not what makes the work distinctive, even if they are what causes its distinctive style.

Other than her colours, Heilmann’s distinguishing characteristic is more in the seemingly nonchalant way in which she makes her pictures. The key components of that are mutability of structure, ambiguity of space and implication of movement.

That mutability may have emerged from how, when she started painting, she wasn’t really thinking about painting but about structure, she says. Her irregularities extend from the casual geometry to the mixing of motifs within a painting to the shapes of the pictures, which seem to grow and combine organically in, for example, Music of the Spheres. Such irregularly shaped works can be seen, as Dominic van den Boogerd has observed, as “the painting equivalent of a musical jam session, in which different musicians play together and try to create something new. Suddenly different patterns find themselves side by side.” Heilmann makes sure the processes she follows are visible, and her ambiguity of space is largely a function of how she loves to paint over colours and to partially scrape away layers so we have a mixture of hidden and revealed. That encourages such questions as—in, say, 311 Castro Street, 2001—are we looking through windows in a mint green wall at colours outside? Or are objects depicted by the coloured near-rectangles? In this respect, as well as in the way she deploys ceramics—she may be the heir to Fontana rather than the New York school of painters.

Primalon Ballroom, 2002, oil on canvas on wood, 127 x 101.6 cm. © Mary Heilmann. Photograph: Oren Slor.

Heilmann’s paintings are, of course, static. Yet she also implies movement in two ways which energize the painting. First, there is that sense of approximation and contingency; we feel things could have been different, matters just happened to come to rest here—and we can see the movements of the fingers or brush which brought us to this place. Second, her shapes are often readable as sequential presentations of a repeated element rather than as static presentations of several items. Indeed, that is implied in the title of Pink Sliding Square, 1978, which could show two differently-sized squares, or one square which has moved further away from us as time moves to our right. That comes from a group of works in black and pink which echo a specific punk music colour scheme of the late ’90s, putting them into the moving territory of dance (and, to return to disguised intimacy, are associated by Heilmann with a doomed love affair). The Heilmann stripes, too, could be ripples; indeed, in the chromatically restrained Night Swimmer, 2008, titled from an REM song, they read directly as breaking waves, part of a recent move towards figuration becoming more explicit, also seen in her road paintings.

So what does the whole show amount to? It’s colourfully enjoyable, for sure. The paintings are open-ended and laid-back enough to respond to different narrative possibilities with an air of changeability. Heilmann embraces the contingencies of the world in a manner which runs counter to the tradition in which the rigours of geometric abstraction—Mondrian, Malevich, Newman—reflect the metaphysical and the universal. Yet if Heilmann’s aim is to debunk such pretensions, she does it in such a winning style that it comes across as affectionate rather than critical. It may not be a heavyweight agenda to tease rather than deconstruct tradition, but Heilmann delivers with sufficient zing to carry the scale of the show. ❚

“Mary Heilmann: Looking at Pictures” was exhibited at Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK, from June 8 to August 21, 2016.

Paul Carey-Kent is a freelance art critic in Southampton, England, whose writings can be found at <paulsartworld.blogspot.com>.