Leonard Cohen

The Book of Longing, a collection of poetry and prose Leonard Cohen published in 2006, is about wisdom. Composed by a man who has lived much in the world, and who has come to understand what all that living has been about, it also knows enough to take its wisdom with a grain of salt. While his ability to write remains undiminished, what he writes about has undergone some adjustments. As the poet himself laments, he now aches in the places where he used to play, and his candour in addressing those moments of pain is no less compelling than it was when he articulated his moments of passion. Cohen, in his 73rd year to heaven, remains our most satisfying poet on the complications of love and the loving body.

Consider the opening lines of “The Collapse of Zen,” an erotic poem that shapes itself around a series of rhetorical questions:

When I can wedge my face

into the place

and struggle with my breathing

as she brings her eager fingers down

to separate herself,

to help me use my whole mouth

against her hungriness,

her most private of hungers -

why should I want to be enlightened?

Why indeed, when enlightenment comes with the fleshly territory? I am reminded in reading Cohen’s poem of an earlier declaration of desire written by W.B. Yeats, which also figured out the answer to a question it set for itself. In “Politics,” written only a year before his death in 1939, Yeats wrestles with the competing tug of the personal and the social. He begins by quoting Thomas Mann’s famous declaration that, “In our time the destiny of man presents its meaning in political terms,” and goes on to ask how is it possible to “fix his attention” on politics in the presence of “that girl standing there.” Yeats is only marginally prepared to admit there may be something in the positions taken by men of the world and politicians:

And maybe what they say is true

Of war and war’s alarms,

But O that I were young again

And held her in my arms!

It’s clear that the real truth lies in transformative youth and physical passion. Cohen, for his part, won’t buy back into time, but he holds resolutely to the passionate body. “My heart is broken as usual,” he says near the end of “The Collapse of Zen,” “over someone’s evanescent beauty.”

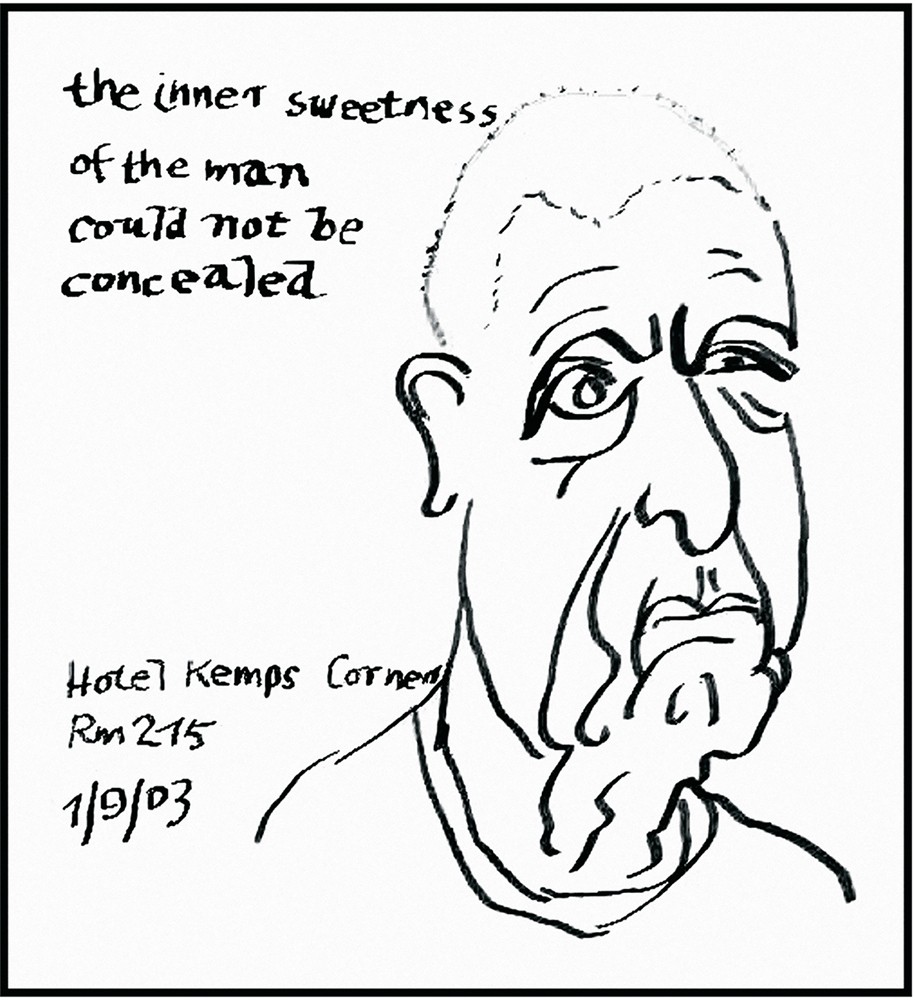

Inner sweetness, 2007, pigment print, 15 x 12”, edition of 100, Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

While the quest for beauty has been at the centre of Cohen’s life and art for over 50 years, it has not blinded him to mankind’s dangerous tendencies. In this regard he leaves Yeats behind and bivouacs with Thomas Mann. He claims he is too old to “learn the names of the new killers” but he is aware of “their old obsolete atrocity / that has driven out / the heart’s warm appetite / and humbled evolution / and made a puke of prayer.” Earlier in “The Collapse of Zen” he observes that “the tender blooming nipple of mankind / is caught in the pincers / of power and muscle and money.” A number of these poems play the same chord as the songs in The Future, Cohen’s prophetic and brilliant album from 1992. He has seen the future; it works; and it is murder.

Cohen’s wisdom is in his ability to bring together the cultures of conscience and love. He writes in “The Mist of Pornography” that one of the functions of poetry is to overthrow vulgarity / and set America straight / with the barbed wire / and the regular beatings / of rhyme.” To recall Yeats again, a touch of mocking mockers emerges in the formulation. How effective a punishment is being beaten by lines of poetry; how likely is it that the pincers of power will be replaced by the barbs of rhyme?

Finally, though, Cohen is redeemed by love. In the light impression we make on the skin of the world, “it is in love that we are made; in love we disappear.” Making and unmaking, the loved and the lover. In Cohen’s wise construction of the world there is no way to tell the poet dancer from the poetic dance.

The following interview combines two telephone conversations recorded from Los Angeles on May 7, and May 12, 2007. The drawings by Leonard Cohen were included in an exhibition called “Drawn to Words: Visual works from 40 years” that premiered at the Drabinsky Gallery in Toronto on June 3, 2007.

LEONARD COHEN: The proofs were printed by Graham Nash who has a state-of-the-art printing facility on the beach. I think we printed 56. Quite a few, which are in colour, aren’t in the Book of Longing. A number of the images in the book were details of larger works in which the colours are very rich and the blacks very black. The medium for the drawings ranges from watercolours to oil pastels, to a number of combinations of those, which are then put in Photoshop. A lot of them were drawn on a Wacom tablet with a free-standing stylus fit right into the computer. So it really runs from doodles on napkins to watercolours, oil pastels, charcoal drawings, right up to digitally created images.

BORDER CROSSINGS: So you go from doodles to an image that you consciously sit down to orchestrate. Does that cover the way the work comes to you?

LC: Well, you know, just as play is deadly serious for children, so doodles are deadly serious for me.

BC: My question wasn’t about forming a hierarchy as much as the way the Muse comes to you. I’m interested in the relationship that exists in your mind between the drawing and your work as a poet, songwriter and novelist. Do they come from the same source?

LC: I think one is relief from the other. I always drew and when my kids were growing up a large feature of our family activity was to sit around the kitchen table with a lot of different kinds of material and draw. That’s always been what I’ve done, especially in Greece when there seemed to be a lot of time, or when the kids were growing up in Montreal. Then I got interested in computers. I don’t know if you remember, but at a certain point Macintosh gave free computers to Canadian writers, including Margaret Atwood, Irving Layton, and Jack McClelland. Not only that, they were kind enough to provide tutors who actually came to my house and helped me set up and showed me how to work it. So I got interested in the Macintosh computer quite early.

BC: When you say you’ve always drawn, how far back do you mean? I’ve read that you determined at an early age that you were going to be a poet. Was drawing also always part of your expression?

LC: It was just one of the things that I and a number of my friends did. I grew up with the Montreal sculptor Morton Rosengarten and we always drew together. He, of course, did it professionally but I never remotely thought of it as anything that would be treated professionally. I didn’t expect it to have a public face.

BC: Your whole career has been a series of abdications from doing anything that might be regarded as professional. At least that’s what you keep saying.

LC: “Career” was a word that didn’t really describe what I was doing. Of course, I’ve had to re-examine that notion very carefully in the past couple of years. I found out I better have a career because I don’t have any money left. I guess a career was always a necessity but I never thought of it that way. I wanted to be paid for my work but I didn’t want to work for pay. I would never have used the word “poet.” “Writer” is the word I use because, as I’ve said elsewhere, I think poetry is a verdict that other people make about your work and it’s not appropriate to claim it yourself. It’s a description of a very high degree.

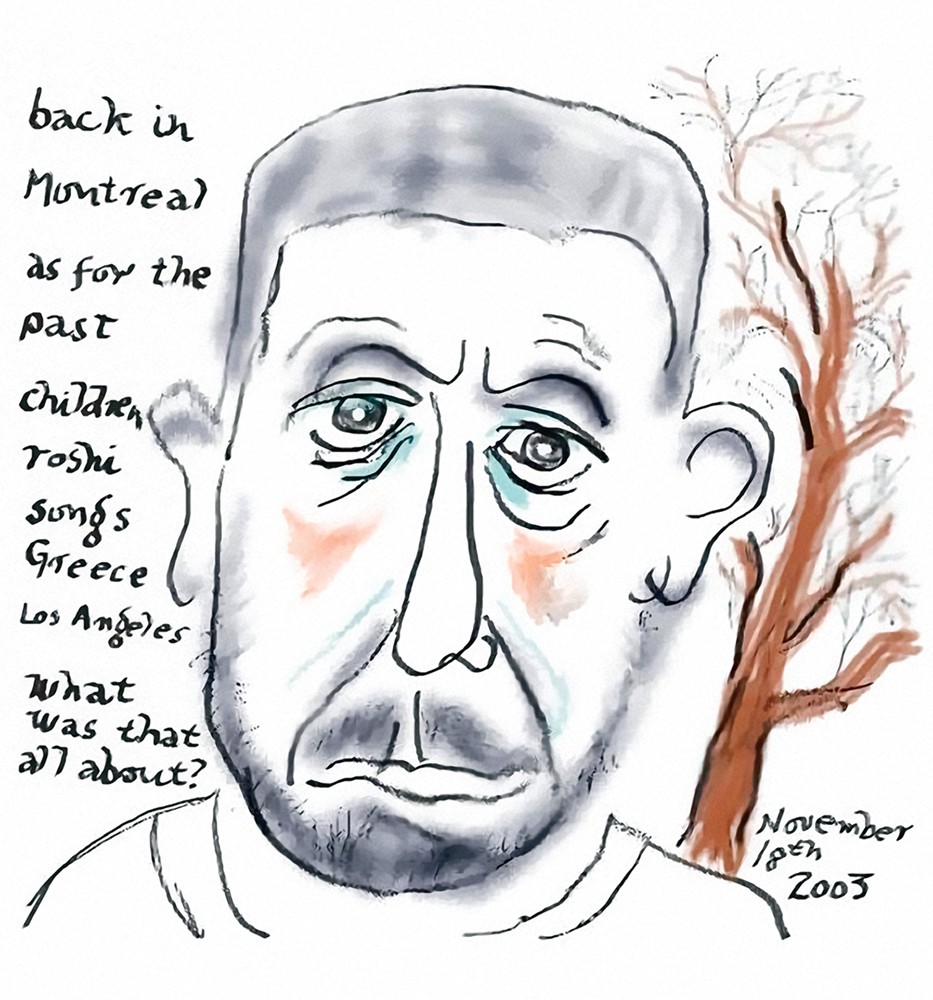

Back in Montreal, 2007, pigment print, 15 x 12”, edition of 100, Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

BC: So your modesty in not referring to yourself as a poet isn’t disingenuous?

LC: I know the league I’m operating in. I don’t want to claim modesty, either, because that is another title. But you know there is King David, there’s Homer, Shakespeare and Dante. When I read Layton, I see the conviction and dedication to the whole enterprise, so I don’t think it’s difficult to see what I mean. As I wrote in the preface for the catalogue to these drawings, if my songs were the only songs in the world, they’d be really important, and similarly with my poems. But you get into line and if you have even a passing acquaintance with what the tradition is, I think it’s appropriate to recognize that you’re not going to be at the head of that line. That’s all I mean to say.

BC: When you published your first book, you were surrounded by a cluster of remarkable poets, including A.J.M. Smith, Louis Dudek, Irving Layton and A.M. Klein. Montreal was a pretty hot place for poetry back in those days.

LC: I think it probably still is. But there were a couple of street poets—Henry Moskowitz and Philip Tetrault—who didn’t get recognized. There were really good poets in the city but I think Irving had such a compelling public projection because of Fighting Words. He brought poetry to a larger audience and he dignified the enterprise in some kind of way, although poets don’t need too much encouragement to figure themselves important. When we met, we considered it a kind of summit meeting and that great affairs were being determined.

BC: You’ve said the poets you were writing to were writers like William Butler Yeats. I assume you could take for granted a tradition that happened to take poetic form in Montreal?

LC: I felt we were part of something. I felt also there was a certain power in the fact that we were provincial, that we weren’t American and that we weren’t English, that somehow our freedom and our rights were protected. By being in this backwater, we could come into it from a position that was a little fresher, a little less burdened by the tradition, but very much aware of it at the same time.

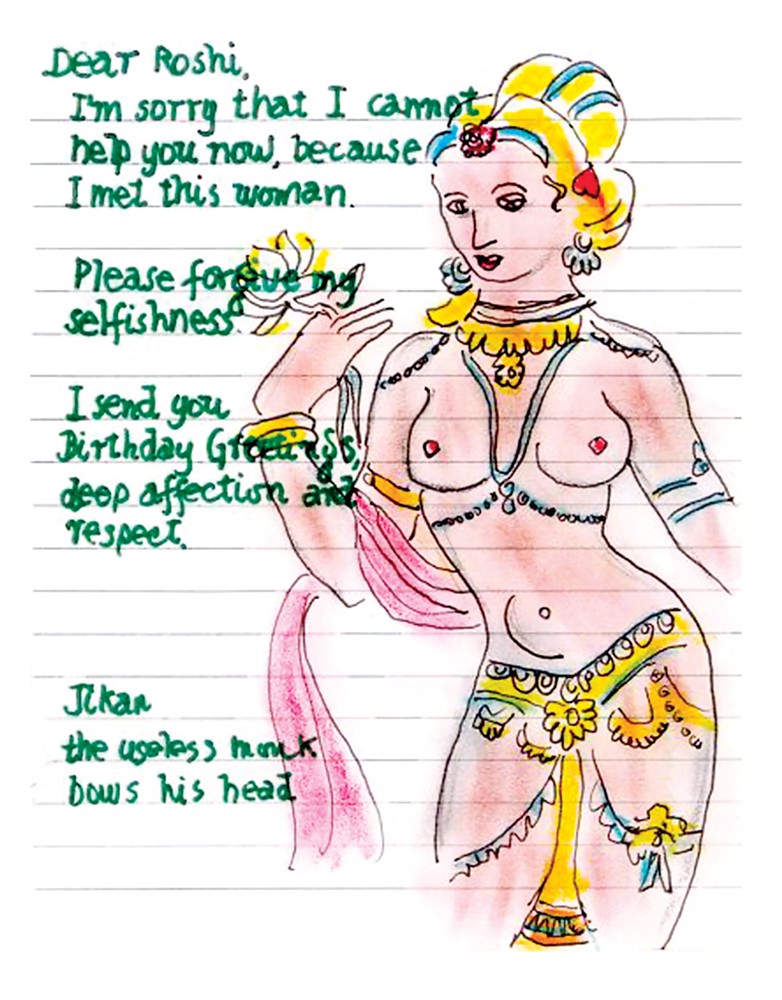

Deeply familiar, 2007, pigment print, 15 x 12”, edition of 100, Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

BC: A.J.M. Smith had a notion he called “eclectic detachment” through which Canadian poets could choose the tradition they wanted. I don’t know about the detachment but the eclecticism seemed desirable. You could form your own poetic tradition because you weren’t in thrall to either of them.

LC: It’s something like that. There was a lot of wiggle room. Also, you weren’t being judged by anyone because nobody cared. There were no prizes, there was no Canada Council, there were no women.

BC: You mean you couldn’t even get laid by writing a poem? That can’t be true.

LC: Pretty much. And there was no money. We were putting out those early publications on mimeograph machines. Nobody felt a chip on their shoulder that they couldn’t make it as a writer because nobody expected to make it as a writer. So there was an absence of self-pity about the whole thing and people were in it for the activity itself. When we’d meet and read each other our poems, the criticism was savage but it was our thing. It was La Cosa Nostra. I remember Frank Scott reading a poem-Phyllis Webb was there and Irving and Dudek and Ursula and Bob Currie—and it was torn apart and he started crying. Everybody was in their cups. He was the Dean of the Law School at that time and he said, “You’re right, it was a weak poem and I’ve spread myself too thin.” That was the atmosphere. It was rigorous and you had to defend every word. I don’t know if that goes on any more. I get a considerable amount of mail from young poets and they’re mostly interested in getting published and somehow advancing their position in some fictitious world of poetry they think exists.

BC: And not in the rigour that made Emily Dickinson consider every syllable, yet alone every word?

LC: Those were the terms in which we had to defend every word and it did often get ugly. But the general feeling was that we were engaged in an important and noble enterprise and that you gave yourself to this without any hope of anything other than the possible claim that you were part of it, that you deserved to be numbered among the great ones.

BC: So you publish two books of poetry that get well reviewed, as well as a novel, and throughout this entire process you realize you’re not going to make a living as a writer. It’s as if the residue of Montreal continued to haunt you even after you’d become successful.

LC: I wasn’t surprised that I couldn’t make a living out of poetry. I thought maybe I could make a living out of the novel, which in my case wasn’t that far from poetry. There was a moment when I realized there were bills I couldn’t pay, so it wasn’t a difficult revelation. In retrospect, I’m not sure what made me think that becoming a musician or a singer was going to address the economic crisis, either.

BC: I’ve always admired your poem “For E.J.P.,” which opens, “I once believed a single line in a Chinese poem.” In it you make reference to Ezra Pound’s Chinese poetry. The poem is dedicated to E.J. Pratt, it quotes Pound, there is in it a hint of Rilke, even Robert Browning. I read the poem as a compendium of other poets to whom you were paying direct homage.

LC: That’s a good insight. I dedicated it to E.J. Pratt because I had met him, not because he influenced my work at all. I just had tremendous respect for what he’d done in Canada and his person was very, very appealing. But those echoes are in the poem, especially the Chinese poets.

BC: Has language always been a repository of its own previous use for you?

LC: I think it was A.E. Housman who said it either makes the hair on the back of your neck stand up or it doesn’t. I think there are certain rhythms and connections that for some odd reason use the vehicle of language to deeply penetrate into your psyche, your feelings, or into life itself. I think each writer (in fact, I think everybody) has a few of those rhythms, of what they consider highly charged language. Both the message conveyed and the conveyance itself take on tremendous significance. Because you’re standing as a young boy in synagogue and you hear the words from The Memorial Service for the Dead, “Lord, what is man that thou regardest him? or the son of man that Thou takest account of him? Man is like to vanity; his days are as a shadow that passeth away. In the morning he flourisheth, and sprouteth afresh; in the evening he is cut down, and withereth. So teach us to number our days that we may get us a heart of wisdom.” So both the meaning of what is conveyed and, more importantly, the rhythm of the language imprint themselves. I think that’s what one goes for, either to emulate, to resist, or to modify it. I think there’s maybe four or five of those patterns that continually compel you, or invite you to recreate that highly charged moment.

BC: In a song like “If it Be Your Will,” are you playing off rhythms that come out of Judaic culture? On a number of occasions you have deliberately invoked the sound of that tradition.

LC: Yes, because it is a powerful tradition. Just the formulation of “If it Be Your Will” has that quality. There are many prayers that have that refrain. There are a lot of references and echoes to both Christian and Jewish traditions.

BC: So it’s no accident that your first book would be called Let Us Compare Mythologies. That would be a description of how your imagination functions?

LC: I think that’s so. Temperamentally, I’ve always resisted the claim for the unique truth of one particular model, and, growing up in Montreal, one had powerful versions of Catholicism, Protestantism and Judaism. It didn’t involve a real stretch to be affected by those traditions. It was natural.

BC: Did you systematically set out to learn the traditions?

LC: At different points in my life I seemed to be involved in a closer study than at other times. For instance, when I was a secretary to my teacher, Roshi, it was at a time when there was a kind of rapprochement between Zen and the Roman Catholic church (through people like Thomas Merton). So my teacher, who was probably the heaviest guy around in North America, was invited to the headquarters of the Trappists in Massachusetts. I would accompany him to a lot of these Catholic monasteries in which I would participate in the setting-up routine while Roshi was leading meditations.

BC: So you lingered in North American monasteries but not in European ones?

LC: That’s right. I did linger in a number of them and I would talk to the monks and get a feel for things apart from what I was reading, like Simone Weil. I remember an older monk with whom I became friendly. I said to him one day, “How’s it going?” and he said, “I’ve been here 12 years and every morning when I wake up I have to decide whether or not to stay.” It’s a rough life.

BC: You stayed a while and then decided that the spiritual life wasn’t for you. Did you come down from the mountain somewhat discouraged?

LC: I was privileged to have a friendship with Roshi so I took certain personae for the poems as a way of bringing something across in a rather lighthearted way. I’m reluctant to answer your question, because I’ve already answered it in a number of the poems at the beginning of the Book of Longing, like “Leaving Mt. Baldy,” “My Life in Robes,” “His Master’s Voice,” “When I Drink” and “The Lovesick Monk.” So your question hits the nail on the head, it’s just that it took a whole book to answer it. But I spent many years with Roshi and the friendship continues. I’m not living there but whenever he comes, I see him. Incidentally, he just turned 100 and we had a great party. We were having a drink a couple of years ago when he was 98—he’s a good drinker—and he poured his glass, poked me in the arm and said, “Excuse me for not dying.”

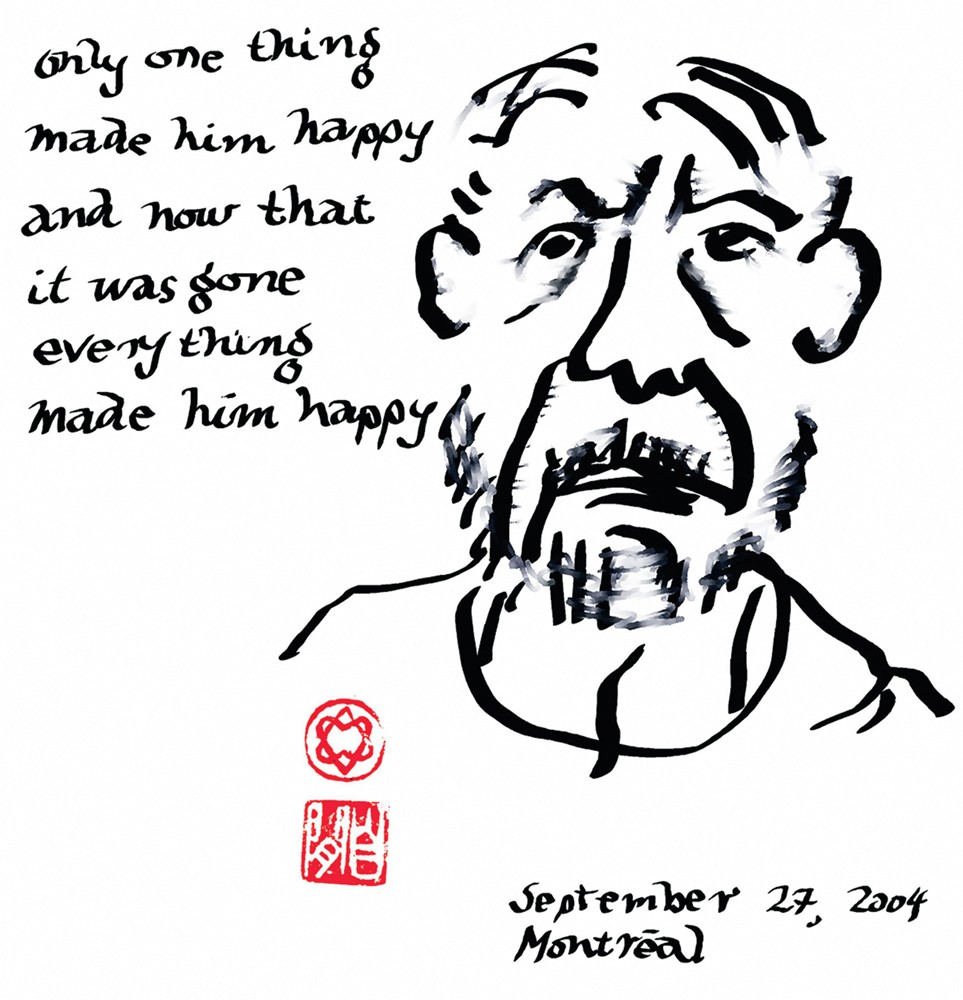

One little guy, 2007, pigment print, 15 x 12”, edition of 100, Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

BC: You mention the word “persona.” How much are we to read the work as a series of masks that can be put on and which we shouldn’t take as literal positions you hold? Can they be seen as creations or characters?

LC: I see it more through the prism of a friendship you have with the reader, or with someone you’re writing for. It’s the kind of disclosure that goes with friendship, that kind of confidentiality. I think the essence of friendship is that you always let the other person off the hook.

BC: It’s essentially a generosity?

LC: It is a kind of generosity. It doesn’t mean to say you have to buy it and that nothing hangs on it. I tried to put that in a song called “The Night Comes On,” which goes: “and here’s to the few / who forgive what you do / and the fewer who don’t even care.”

BC: So are the songs scans of sensibility to which you commit yourself? Is that why you often thank the reader for coming into the room with you?

LC: I do feel that. You don’t want to name these things too carefully because that is also one of the characteristics of friendship: you don’t name it. You don’t want to say to anyone, “You’re my best friend.” So they are expressions. I do feel the liberties and the mild responsibilities that go with friendship.

BC: In a self-portrait called Too Tough for Us, you draw yourself with the crazed concentration of a Shunga figure, minus the visible sexual apparatus. The self-portraits run a fair range, from self-ridicule through to a recognition of aging. I gather that’s a deliberate scoring of where you find yourself?

LC: That’s exactly it. At certain periods of time, I would do a self-portrait to begin the day. I have hundreds of them. For a year I did one every morning. I’d brew a pot of coffee, light a stick of incense—I don’t smoke so it’s the closest I can get to it—and then do the drawing. There’s a little mirror on my desk and I just draw. Then I look and see what expression is there, what is the guy saying, and I annotate it. It’s a very accurate presentation of the moment and nothing more.

BC: You call them “acceptable decorations” in the piece you wrote for your exhibition at the Drabinsky Gallery in Toronto. There’s a kind of generous accuracy and— this may be a word that sticks in your craw—a courage about them.

LC: I don’t mind somebody else using it as long as I don’t have to. I say in one of the poems in Book of Longing that I can’t claim anything for this path. There’s nothing one can say about it, it’s just that sometimes you bend down over your labour and you know it’s okay, it’s not the greatest thing, it’s acceptable. A friend wanted me to call it “transcendent decorations,” but I said that was too self-congratulatory. It’s acceptable in the sense that it gently refers to a lot of things we know in the pictorial tradition. It doesn’t have to participate in the current artistic enterprise, which is involved with originality and some kind of abrasive assertion. I don’t pretend to understand what is being asserted so abrasively by so many people in the fi eld; it doesn’t participate in that kind of world. I use images that refer to things we’ve liked in art. That’s the way I feel these come off, although that was never my intention. My intention was to make something that was accessible and with which I could decorate my notebooks.

BC: Very often the relationship between the self-portraits and the women reminds me of what Picasso was after. There’s almost a dialectical representation in the drawings: beauty is there in its plenitude and you’re there in the guise of self-ridicule and self-mockery.

LC: That’s a nice way to put it. This attention to the drawings is very recent. People have been asking me about writing for about 50 years, so you get a rap, but because I’m not up on the way people talk about art, I don’t know the score. I haven’t had that chance and maybe that’s good. I was never compelled to come up with an apology or a manifesto. To me, “acceptable decorations” is very close. Not to use decoration in a pejorative way but as a legitimate vehicle of pleasure or delight.

BC: In a drawing like The Grecian, I’m reminded of what Hockney did in his Celia drawings. In the same way that language has its own history and its own ear, maybe the eye does, too.

LC: Yes, I think so. I don’t know the particular series you’re talking about but I know his work. I think that everything everyone has ever seen is there, especially if what you’ve looked at is really good.

BC: One of the lovely refrains you have is “do not decode / these cries of mine, / they are the road, and not the sign.” I’m interested in the work you’ve done in all forms as a process you can decode, which does tell us something about your life and your attitude towards living. I guess what I’m saying is they’re not just constructed masks but they’re about what you’ve done and how you felt about the world.

LC: Communication exists on so many levels. Like in the interpretation of the Bible—there’s the narrative, then there’s the aphoristic, then there’s metaphor: it wasn’t really about crossing the Red Sea, it was about liberation. Then the mystical, in which these are formulas for meditative exercises that are liberating. So you can get into that kind of thing. But the caution I was trying to present there was that this is also about what really happened. When I say “tumbled up in formless circumstance,” I mean that’s what happened. I was sitting there and the light came in through the window and it really did happen that way. In that moment I was trying to indicate that a cigar is a cigar.

BC: I like the way your written introduction focuses on what’s in the room with you. So the candlesticks and the bowls and the fruit, even the table, become utterly important. Does a lot of your work come out of that engagement with the quotidian, with the vernacular?

LC: I’ve always had beautiful tables. In Greece I had a really good kitchen table, which somebody gave to me, and I still have three or four good ones in Montreal. I got this feeling of freedom about tables from Michel Garneau, a Quebecois writer who just translated Book of Longing. He lives across the street and he brought Rosengarten and me to that neighbourhood. I went into his little house and the whole downstairs was just a rectangle and a table had been built on three sides of the room, permanently, against the wall. He said, “I spend my life at tables, so I might as well have a good one and a big one.” I’ve taken the lead on that and I have some really big tables. The one I’m standing in front of right now is nine feet long and three and a half feet wide. A friend of mine, a Seventh Day Adventist, made it for me. He made me three or four of them.

BC: In “The Mist of Pornography,” you talk about the “impeccable order of objects on a table.” It is about the satisfaction that comes from seeing one thing in relation to another.

LC: What really makes it so sweet is to have the time to absorb those things—the ashtray, the candlestick, some pieces of fruit. It stands for the order we can’t acquire in our own psyche.

BC: And in our own emotional lives? Is this what you call refuelling; sitting at a table is a chance to do that?

LC: Yes. It’s just a delight. You don’t want to make too much out of it because these things come upon you with their own sense of urgency at the appropriate moments. You don’t want to get into some kind of disciplinary action where you’ve got to see the thing perfectly all the time. The moment arises when they assert their beauty and their unassailable perfection.

BC: Is that recognition something that comes with experience and wisdom? The simple is one of the most difficult things to achieve.

LC: First of all, you have to have something in you that responds to that kind of idea, and then it’s activated by the people, the artwork and the expressions you bump into. When I was quite young, I used to love Japanese watercolours and paintings. I don’t know what it is that made me respond to that, except that it’s glorious. It’s also empty.

BC: The beauty of the floating world isn’t necessarily something that would come naturally.

LC: It has to resonate with something that’s already there. Also, when we were setting up our rooms around Montreal, people like Rosengarten and myself, we’d go to the Salvation Army and find a good table and a good chair and bring it back and somehow it filled the room. It was glorious. You don’t want too much else; “I choose the rooms that I live in with care, / the windows are small and the walls almost bare, / there’s only one bed and there’s only one prayer.” That was one of the first songs that I wrote and it was really true. My sense of the voluptuous involved that kind of simplicity. It wasn’t simplicity I was after, it was the opposite, the voluptuous feeling of simplicity. I don’t want to get too paradoxical but that was what was beautiful.

BC: You don’t often hear someone talking as a voluptuous puritan. You’ve also said you’ve never had much inspiration. So where does the art come from? If it doesn’t come out of that ignition, is it about the careful observation of the world?

LC: There was a tiny poem that I left out of the Book of Longing. It had a wry self-portrait and it was called “My Career”: “so little to say, so urgent to say it.” I don’t know why I left it out. Maybe it was too close to the bone.

It was the hat, 2007, pigment print, 15 x 12”, edition of 100, Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

BC: When you talk about the “mysterious impreciseness” of your art, where is the imprecision?

LC: There are 300 self-portraits and none of them looks like me.

BC: But they all look like you.

LC: Yes, that too. From a certain point of view, that’s not what I’m going for. Occasionally they do actually look like me and they satisfy those criteria.

BC: What about the drawing called Jikan? To pull a phrase from Rumi, it looks like you’re a member of “the caravan of despair.” It does cover an aspect of your melancholy.

LC: I think that’s the one called The Mysterious Imprecision. We couldn’t get the blacks. That’s of course what I’m going for: the picture of the inside.

BC: Rumi has that lovely notion that it’s through the wound that the light gets in. Is that your source for Anthem?

LC: I did read Rumi a lot, especially when I was younger.

BC: I guess it’s a simple recognition of a process of salvation, that if life is this impossible enterprise, then we have to find a way to salvage something from it. Recognizing that the wound is also a way for illumination to occur is a perfectly sensible way of viewing the world.

LC: You know when Moses came down from the mountain and saw the Children of Israel worshipping the Golden Calf, he threw the tablets to the ground and they broke. Then he went back up and came down with the full set again. Now, the interesting thing—and it’s not in the Bible but it is in the oral tradition—is that when they built the tabernacle, they put the broken ones in with the whole ones. They kept the broken ones, as if to say this also is part of the immutable, inflexible human law. We are broken. Many years later, the Hassids would say that “from the broken fragments of my heart I will build an altar to the Lord.” That sense of brokenness is impossible to avoid today. It seems to be clearer today than it was when I was young, so I say it over and over again, “there is a crack in everything / that’s how the light gets in.”

BC: The Future was an extraordinary album. That cluster of poems seems to stand in the same relation to our epoch that T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land did to his. Did you have a sense in doing it, or a sense now, of how radical a statement it was?

LC: I do and I was disappointed that nobody got it because it didn’t really do very well. It only sold 60,000 or 70,000 copies in America and those numbers don’t compel any serious interest or examination. It sold better in Europe. But when the Berlin Wall came down, there was general rejoicing and I must have been the only person who wasn’t rejoicing. I felt it was going to present a tremendous disequilibrium. That’s why I say, “give me back the Berlin Wall / give me back Stalin and St. Paul,” because this is not the beginning of a period of liberation. As I say in a poem in one of my early books, the victor in the Second World War was freedom, but freedom to do horror. And that’s what I felt when the Wall came down, freedom to murder. “I have seen the future and it is murder.” It’s only recently, because I get sent things from the Internet, that those poems are being talked about. It’s really gratifying because people are recognizing that I had the feeling and I said it. Again, I don’t know what it is. As I’ve said, if I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often. But I knew that was seminal at the time. It goes with the territory, you feel that this is really good.

Dear Roshi, 2007, priment print on paper, 30 x 20”, Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

BC: Do the drawings occupy the same register as the songs? Do they elaborate the same ideas about self and society but just in a different medium?

LC: I guess they do, but not intentionally because I didn’t prepare them over the years for display. But of course they participated because they were made by the same guy. I just never imagined them. When I see them now, they look true and like acceptable decorations. They don’t ask you to know everything there is to know about the tradition and about what’s going on. On the other hand, they don’t insult your intelligence if you don’t know what’s going on. That’s what I mean by their acceptability.

BC: I’m interested in your notion that you cut personality away from the work of art. T.S. Eliot said that poetry was an escape from personality and not an indulgence in it. I wonder what role personality has played in your work?

LC: I’d elaborate on what Eliot said, which is that every sense of peacefulness derives from the degree to which the personality is forgotten. I think that peace and personality are mutually exclusive.

BC: So, in a sense, the abdication of self is the way you find the richest aspects of yourself?

LC: I think it’s the only time you can relax. Who it is that is relaxing is precisely the unexamined elephant in the room. As soon as you examine who is relaxing, then you’re not relaxing. It’s exactly as you say. It’s the abdication of the effort to maintain the heroic dimension of your life that is personality. When that dissolves, you can lay back for a moment or two. You can’t live that way because obviously you need a self, an ego and a personality to interact with all the other selves, personalities and egos. But that dissolves in those blessed moments we call grace.

BC: There is in your work the idea that beauty is the way the world can be judged and understood. The quest for it seems central to what you do.

LC: Nothing arises in me to dispute the idea that the quest for beauty is central to my life. I certainly wouldn’t resist it. I sometimes hear it more as gossip than anything I can get behind, but I think that conversation about these matters is completely legitimate.

BC: What’s changed over the years?

LC: My life was very painful for no reason that I could discern. Most of the time the background was anguish and almost everything I did, from the pursuit of women, drugs and religion to my monastic life, was to address this problem. The cover story was successful: I had money, I had fame, I had most of the things people want. So I felt ashamed about feeling bad. But honestly, to get from moment to moment was extremely difficult. The sense of anguish was acute. What happened was that the background of suffering totally dissolved. Whether it happened because of the 30 years I spent with my dear and beloved teacher, or whether it was the couple of years I spent subsequently in India with another great teacher, I don’t know. I read somewhere that as you get older, certain brain cells associated with anxiety die in some people. In any event, what happened was that I stopped suffering.

BC: Was this an epiphany, or was it gradual?

LC: It happened by imperceptible degrees over two or three weeks. I didn’t even know it was happening, I just woke up one day and I said to myself, this must be what people feel like, I don’t feel great, I don’t feel bad. I know that if something bad happens, I’ll be bummed out, but everything is okay, the background has dissolved. It’s just an ordinary day, it isn’t a struggle, it isn’t an ordeal.

BC: So the cloud that hung over everything disappeared?

LC: It dissipated. People ask me—was it the meditation, was it the discipline?—and I can’t say. Something in me is deeply grateful and I don’t know who to be grateful to. But it doesn’t really matter. I just feel this sense of gratitude. That’s why when I had lost everything, my friends wondered why I wasn’t destroyed. It was pretty dramatic and people around me were waiting for me to fall. But it didn’t mean fuck all because I felt good. When it all comes down to it, everything is about mood. I don’t ask the Lord to be tested but you can be in extreme circumstances and if your mood is okay, your mood is okay. My mood has been good.

BC: I love your notion that life is designed to overthrow you and that nobody masters it. You seem to be doing pretty well on the mastery level.

LC: But listen, you can’t claim it. It can come and go. You can’t build a house on it, it’s given to you and all you can do is say thank you.

BC: When the black cloud lifted, did it have any effect on your creativity?

LC: On the contrary. It’s true that sorrow and suffering are the spur or the thorn that often does invite a response in certain kinds of creative individuals. When I say that the background of anguish disappeared, I mean that something that was imposed on my nature was removed. My own nature, which responds to suffering, to sorrow and to melancholy, had been freed to respond authentically to whatever emotions arose. So I wrote and produced Anjani’s record, I finished Book of Longing and I’ve been at it ever since with a kind of graceful intensity that hasn’t abated.

BC: Did it occur to you that there might have been a methodology that would help you get rid of the way you were feeling?

LC: I tried everything. I tried wine, women and song in a really serious experiment. It wasn’t all hard work but it didn’t work, either. And then at the same time—these experiments were often running concurrently—I tried all the conventional antidepressants. None of them worked. I got to the point where I pulled my medications out of my shaving kit where I kept them and threw everything away. I thought, that’s the end of it, I’m not trying anything else, I’m going to face it, I’m just humiliated by the attention I’ve given to medications that don’t work.

BC: Had you resolved yourself to the fact that this anxiety would be a condition you would have to undergo for the rest of your life?

LC: That was the spontaneous thought that arose. I had also been given herbal and organic remedies because people were kind, especially in a monastic situation. They want to be helpful and a lot of them were into New Age solutions, which I’m not. I prefer conventional approaches. But I said, “I’ve had it, I can’t do this thing anymore, so screw it. I’m going to go down with my eyes open.” Things got really bad and that’s when I said to Roshi, I’ve got to get out of here; it’s too hard now. Because that life is designed to overthrow a 20-year-old. You get up very early, you don’t get enough sleep and you’re doing physical labour. I’ve talked to Marines about this and it’s like boot camp training. If you’re an ordained monk and an officer of Zendo or the administration, the life is vigorous. You get up at 2:30 to prepare the stove, especially if it’s the winter, then at 3:00 the chanting begins, then there’s two hours in the meditation hall, then breakfast and clean-up before the work bell. Then there’s work—shovelling snow, cooking, cleaning, and the carpentry necessary to keep the facility going. There’s another couple of hours of meditation in the afternoon, then supper—there may be 20 minutes, rest—then maybe two hours more until about 9:30. That’s the regular week. But every four weeks there’s a full retreat, which is 16 hours of rigorous sitting. Every half hour or so you walk around and shake out your legs but basically from 3:00 in the morning until 10:00 at night you are in the meditation hall with short breaks for meals and one-hour-long work periods. There’s a few things you learn whether or not you achieve enlightenment, which I wasn’t going for, I was just trying to feel better. But whatever your thing is, you’re going to get into good shape and you’re going to stop whining. I mean, there’s no point.

Only one thing, 2007, pigment print, 15 x 12”, edition of 100. All images courtesy Drabinsky Gallery, Toronto.

BC: So if you were already aching in the places where you used to play, this life would have made things that much more difficult?

LC: Exactly. So I said to Roshi, I’m going to go down and poke around. He’s very understanding and he asked, “How long will you be gone?” and I said, “I don’t know.” One of the monks had given me a book by Ramesh S. Balsekar and his writings had started to intrigue me in my last few weeks on Mount Baldy, which were very difficult. I’d been reading him, he’s a former president of a branch of the Bank of India, with a lot of pleasure and I don’t know why—I don’t know why anybody does anything—but when I came down the mountain, I thought, I’m going to look him up. I found out he was still alive. I went to San Francisco to get a visa for India, and within 48 hours I was sitting with him in Bombay, and then that curious thing happened that I described to you. By imperceptible degrees, this thing lifted. I felt terrific, I felt, I’ve got a shot at it. I hadn’t been able to establish any relationships. You’d choose somebody you thought could get you out of the fix, and then you weren’t out of it and you would blame them in some secret chamber of your heart. I could never enjoy the love and the companionship because I was in it for completely different and selfish and divergent reasons. So nothing worked. I mean, I was skillful socially, so I could put on a decent face and come up with the right excuses. But basically it was because I couldn’t penetrate this gloom. Then the gloom lifted and my relationships improved.

BC: Were you ever so full of despair that suicide seemed a possibility?

LC: I’m hard-wired against it, tribally. My thing was more, “Fuck this, I’m just going to go out on heroin,” or “I’m going to go to Thailand and fuck myself to death.” Suicide is so genetically offensive to my scene. You’re not allowed to do it; it’s a law. So I thought about giving up by getting lost in the world.

BC: It’s not as if you weren’t productive throughout this period. Why did you bother?

LC: I was doing good work. I think it’s just part of my training. You just have to contribute, you can’t go on a free ride, there’s work to be done. Don’t forget that my life was operating, it’s just that sometimes it was very, very rough.

BC: There are, after all, tremendously productive alcoholics.

LC: There are. I’ve known a number of them and I’ve always wanted to be one. I was getting close to that. In 1993 on tour, I was drinking three bottles of red wine a day before going on stage. But I paid for it. I was in bad shape and I gained a lot of weight and I had to stop. That was one of the reasons I went up to Mount Baldy, I knew I couldn’t go on with that amount of alcohol.

BC: So in that sense it was a place of last resort?

LC: People have very romantic ideas but a monastery is a kind of hospital where people end up because they can’t make it in any other circumstances. Roshi was aware of what was going on. I can safely say his genius is to be fully aware of your inner predicament but he doesn’t perceive it anecdotally. He perceives it as sculpture. He feels there is something off balance. He’s not interested in how you feel about your parents, or your work, or anything else. Still, he’s a man who needs friendships like everybody else, and so with his friends he will become aware of your actual situation, the name of the woman and the name of your children and what you’re going through. That isn’t absent from his character but in his work, his mission, he perceives the shape of your inner predicament and he moves in it and against it and around it on that level. It’s a very subtle kind of help. The feeling you have sometimes is that he is moving you just to correct an imbalance. He said something to me that was very beautiful. He doesn’t speak English very well but he conveyed the full meaning when he said, “Change religion, okay. Friendship important.” I never abandoned Roshi. I mean, I’m a practising Jew, and I always was, but I still felt myself a practising monk. We’re complex creatures; unless you’re dealing with orthodox people on either side who wouldn’t be tolerant. But my orthodoxy is this other thing where you can hold various positions. I’ve never found any conflicts. ■