Learning from Objects: An Interview with David Altmejd

In the following interview, the Montreal-born, New York-based artist David Altmejd refers to his use of minimalist forms—in this case the stacked geometry of Sol Lewitt—as having less to do with the history of pure form than with the construction of a present-day labyrinth. Altmejd’s insistence on reacting to what is immediate, as opposed to reading what is past, is a useful approach to keep in mind while moving through his work. In his sculptures there are references to various contemporary artists and artistic practices but, in an important way, they are amnesiac. Or, if not forgetful, at least respectfully indifferent.

Consider his signature use of the werewolf, one of the most resilient and promiscuous symbols in popular culture. There seems to be no limit to the layers of meaning that can be applied to this hirsute and toothy hybrid. A staple of gothic romanticism in literature and film, the werewolf is the ideal embodiment of our unregulated, uncontrollable nature. But Altmejd wants to harness that power in an act and through a specific part of the creature’s anatomy. He fabricates only werewolf heads and imagines them as the focal point in a narrative of transformative energy. In the story he tells himself, he is obsessed by the energy that comes from a moment of imagined decapitation. He sees the act—as he regards all the materials and forms in his work—as evidence of a vulnerable beauty, in which the monstrous and the delicate conduct a fancy two-step.

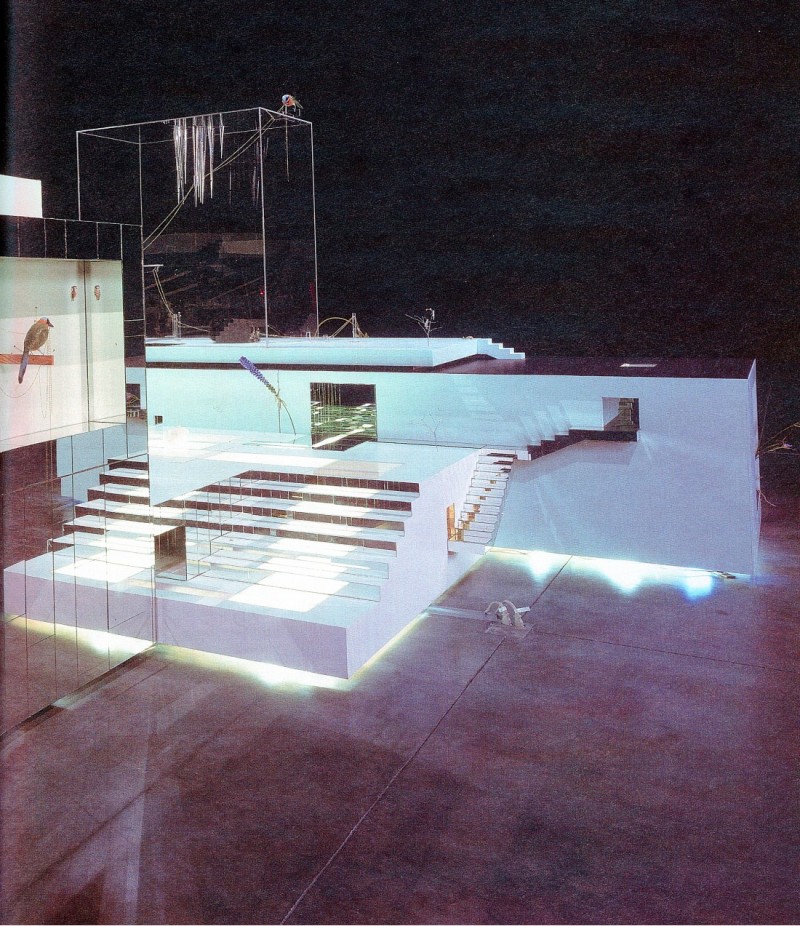

The Sculptor’s Oldest Son, detail, 2004, wood, Plexiglas, cement, plaster, acrylic, 67 x 120 x 72”. Photograph courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

He danced his way into this year’s Whitney Biennial with a large installation (although Altmejd prefers to think of his work as a combination of sculptures) called Delicate Men in Positions of Power. The work looked like the kind of commercial display you might come across in an upscale department store, if it were made by a creative team including Sol Lewitt, Lucas Samaras and Matthew Barney (with the addition of some airy floral and bird arrangements by Anonymous). Altmejd is a material magpie, happy to use plaster, resin, glitter, styrofoam, jewellery, fake hair and mirrors, among much else, as the mix in his particular brand of mixed media. The result, interestingly, is more formal than you would expect, given their composition. Altmejd’s sculptures give off an aura of order and elegance as your eye steps from platform to platform; they speak to an inexplicable logic of materials. This is where his sensibility intersects with Matthew Barney’s; both artists are interested in the development of a new language of form that comes out of unexpected articulations of shape and unusual combinations of things. Their initial interest is in defamiliarizing the familiar, after which the compelling work of making this new language can begin in earnest.

What is most intriguing about David Altmejd’s art—and this may be a characteristic he shares with the best artists of his generation—is a sense of optimistic fearlessness. Regardless of how dark are his sources and origins, his take on them is guileless and anxiety-free. “I see my work as post-apocalyptic,” he says in the following conversation. “The basis is disaster, but then it’s about how things grow on top of that. There’s nothing negative in my work.”

The following interview with Robert Enright was conducted on September 23, 2004. David Altmejd’s most recent exhibition was at the Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York from October 22 to November 27, 2004.

BORDER CROSSINGS: One of the things that strikes me about your work is that a very strong minimalist sensibility coexists with a side that is excessive to the point of almost going for baroque.

DAVID ALTMEJD: I like both things separately and I like their combination even more. The first time I made that association, it was intuitive and it happened by chance. But I was very happy with the result; I felt there was something very personal in there that I had never seen before and with which I felt very comfortable.

BC: Had you specifically been an admirer of Sol Lewitt, Donald Judd and other minimalists?

DA: Absolutely, but I tend to romanticize Minimalism. I got to know about their work in an art history context where it was used to illustrate what Modernism was. I always felt it had something more magical and more worrying. I see Sol Lewitt’s structures, especially his open cube structures, as weird and almost creepy. And, as I say, worrying. A little bit like Borges.

BC: As if they were a maze?

DA: Exactly. I see them less as a purification of form than the building of a labyrinth.

BC: Were you a reader of gothic and romantic literature as a kid?

DA: Not at all. I surfed over it a bit in high school, but I was never really that interested. I see it as a space from which I’ve taken certain images. For example, I imagined the werewolf coming from that kind of space at the end of the 19th century.

BC: I assume you’re not a B-movie fanatic either? If you have any movie in mind, my guess is it would have been something closer to Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast than to An American Werewolf in London.

DA: Absolutely. I don’t watch a lot of horror movies and I don’t read a lot of horror literature, but the first thing people tell me, especially here in New York, is that they think I’m referencing B-movies.

BC: Why has the werewolf become such an interesting icon for you, then?

DA: I guess the question is not necessarily why it came about but why I’ve decided to keep using it. At one point I thought I needed something like that inside my work. I’ve always been very interested in art that refers to the body in a fragmented way, like in Kiki Smith’s work.

BC: And Louise Bourgeois.

DA: She’s one of my heroes. So I just thought that there’s such a tradition of the fragmented human body in contemporary art. Those pieces are always extremely powerful but they’re very familiar in terms of experience. By using a monster body part instead of a human body part, I thought I’d be able to keep the strength and the power of the object but could eliminate the familiar aspect. I felt it was a more interesting experience because it was both powerful and weird. It did become stranger. There is also something complex about the werewolf because he can be a metaphor for being divided into a good and an evil part.

BC: So is it the ignition that comes out of the transformation of man to animal and back again that holds your interest?

DA: I’m interested in energy related to transformation and that metamorphosis between man and animal is super-intense and generates a lot of energy. So I imagine the head of the werewolf being chopped off right after the transformation is over. The head contains all the energy of the transformation. At least that’s the story I invented for myself.

BC: So you don’t see the beheading then as a negative thing but rather as an essential element in that transformative process?

DA: Yes. There’s really nothing negative in my work. I see everything as being positive although I do recognize there might be something macabre about the beheading. But I see it as a starting point. I’m actually more interested in what happens after the beheading. I see my work as post-apocalyptic. The basis is disaster but then it’s about how things grow on top of that.

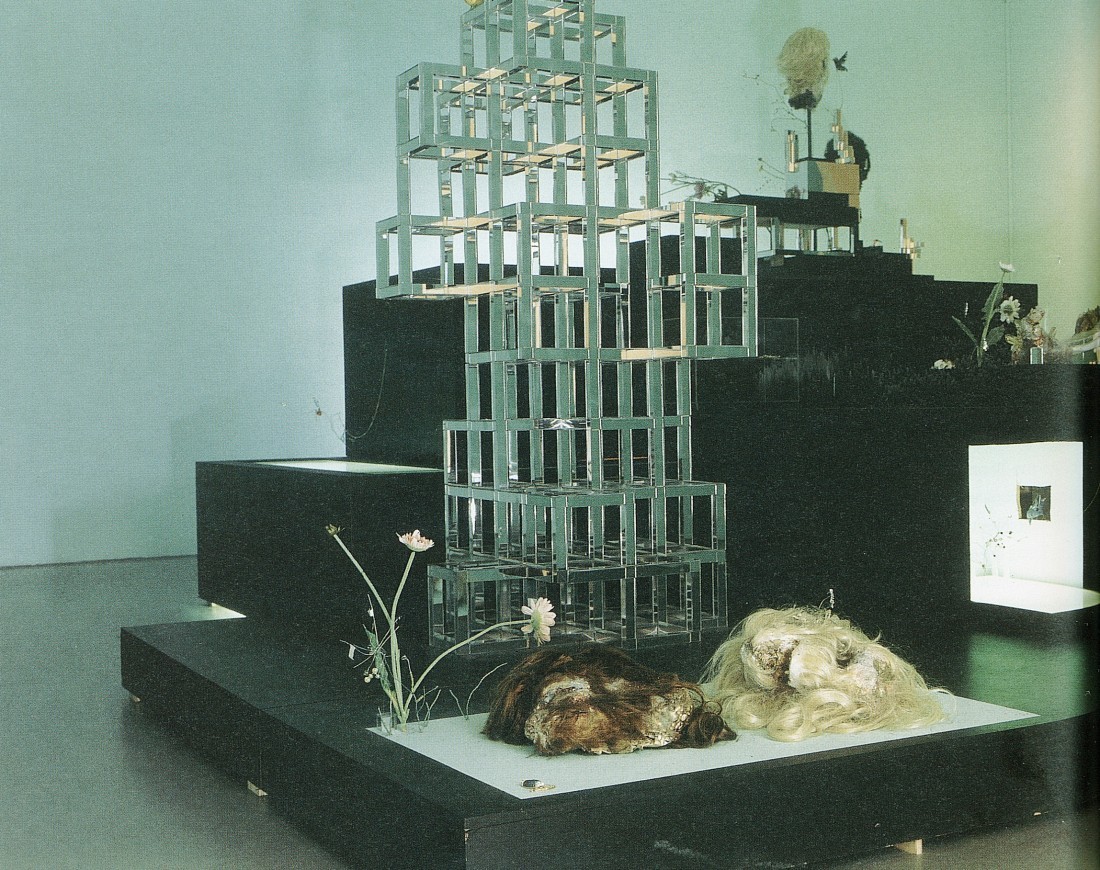

The University 2, detail, 2004, wood, paint, plastic, resin, mirrored glass, Plexiglas, wire, glue, cloth, fake hair, jewellery, glitter.

BC: Dana Schutz operates essentially out of the same logic. Her figures will literally cannibalize themselves, but out of that process she forms a new kind of self-sufficient being. Your generation seems to have been able to ignore things that an earlier generation would have seen as very negative.

DA: Yes. I would say that disaster is not necessarily a negative thing. I see it as a given. It’s more about what you do after.

BC: Is that why the crystal plays such an important part in your work?

DA: There’s many reasons why I use it. I see it as very seductive but it also grows. So I see it as carrying life and energy. Then I start sounding really New Age.

BC: How do you make the decision about what will go where and what will be the nature of the object? Why a Lewitt structure, then a flower, a bird and finally a werewolf head?

DA: Everything happens intuitively. I guess I’m half-quoting David Cronenberg, who I heard refer to himself as a process director. I really understand myself as a process artist. I like it when the piece suddenly starts to make choices by itself. I’m just helping it stay alive, to build itself, and to create its own intelligence.

BC: And you trust that process? When it begins to happen you can give over to it?

DA: It’s the most interesting thing for me and extremely satisfying. I like the feeling that I’m losing control and I’m not the one making the choices. When the piece is finished, I step back and I can’t believe I made it. I would compare it to having children and watching them grow and become individuals. You’re struck by the fact that they came from you but became something even more amazing. I always hope that my work is going to be bigger than me, that it will outgrow me. I want to learn from it. I want it to say things that I never said.

BC: You say the object speaks to you: does that mean there is a narrative going on inside the piece as well?

DA: I wouldn’t go so far as to compare it to the narrative aspect of a novel. It’s more abstract than that. It’s more about combining colours and stuff, and there are no characters. But as a process, it functions in the same way. Because I combine mint green, a mirror and a lot of glossy black, all of sudden I realize that the work is totally like super-high fashion, like a Christian Dior store display. So then I decide to push it in that direction.

BC: One of the things that struck me immediately upon seeing your work is that it does make reference to commercial display.

DA: Except that my work is not well made.

BC: So slickness isn’t necessary for you?

DA: The slick is not good because in my mind it’s just proof of control.

BC: Why do you resist control so much?

DA: I really need to feel as if the piece is not a product. I always want my piece to be an object that carries the energy related to its making. Like process art, I don’t want my work to be an object that is there to generate a certain specific reaction.

BC: Do you think of yourself as a sculptor who makes environments, or as an installation artist?

DA: I think of myself as a sculptor, and I always try not to fall into making an installation. I know that the constructions I make are very sparse; there are a lot of objects but they’re always self-contained on the platform. For me every object is an element and the whole thing is one sculpture. I like the idea that the sculpture could be extremely fragmented and that the process of making it would have many, many layers. I work on some parts in one space and other parts in another space; I’ll work on the heads in my bedroom and on bigger pieces on platforms in the studio. I’m attracted to the idea that the sculpture could actually be made through a very complex process, like a movie. But everything is self-contained on one platform so that the viewer can go around it. I want the sculpture to be seen and understood as one organism, one body. I also like the idea that it’s never-ending. You take two mirrors, place one in front of the other, and it multiplies into an infinite number of reflections.

Untitled (Dark), 2001, plastic, resin, paint, fake hair, glitter, 8 x 14 x 8”.

BC: I’m reminded of Lucas Samaras’s Mirrored Room from 1966.

DA: Yes. I like his work very much.

BC: I know that Matthew Barney visited your studio when you were a graduate student at Columbia. What kind of influence has he had—not specifically on you—but on your generation? Does he open things up for a younger group of artists?

DA: He’s definitely the most important and influential artist of the generation that proceeds me. There’s the way he uses narrative and his way of building a system to generate objects and to generate form. That’s very original and very few artists can do it. There’s Matthew Richie and Bonnie Collura. What they do is invent a system made of characters or ideas or places, but they don’t necessarily talk about that system. They use it to generate objects. There are also other artists who are underrated but who have been extremely influential in this regard. I’m thinking of Paul McCarthy.

BC: McCarthy is an artist whose performances embody the dilemma between control and lack of control.

DA: Absolutely, but in his case it’s more literal. Lack of control in his work means people just throw up.

BC: Is a generational thing going on with you and your contemporaries that would distinguish you from an earlier cluster of artists?

Utitled, 2004, plastic, resin, paint, fake hair, jewellery, glitter, 9 x 12 x 10”.

DA: I wouldn’t be able to tell you what defines my generation, apart from certain tastes and specific references to Pop culture. I feel like my work has been developing independent from its context. Maybe that’s naïve but I can see how it’s evolved in regards to itself and its past, but not in regards to a larger context.

BC: Is it hermetic?

DA: More and more. Before, I hadn’t built enough of a vocabulary to make full sentences. I kept experimenting and taking things from the outside world. Now I’ve done enough to use my own work as an inspiration. I feel that the work is more self-referential now. It feels healthier than ever. Recently I had the idea that I would like to take a step inside my work in order to make something that would evolve within itself. I’ve always made and built sculptures that were sparse and that grew outwards. I thought it would be interesting to explore infinity but towards the inside, in the direction of an inward infinity. So instead of making things grow outside the frame, I would make dig, make holes and make things grow on bones.

BC: What were you getting at in the piece of public art you installed in Central Park?

DA: I liked the idea that it was very delicate. I thought it would be interesting to make something fragile and beautiful and to place a Plexiglas cube around it. It’s the simplest thing in the world and it ended up being extremely weird in the landscape of the park.

BC: You do walk a fine line in your work in which you are able to combine the delicate and the monstrous.

DA: That vulnerable beauty is the only kind that interests me. Perfect beauty is not interesting; it doesn’t exist. Things start to exist when there’s a tension. I know it’s a cliché but I like people with big noses.

BC: Do you care about originality?

DA: I would automatically say no. But I’m touched when people tell me, “I’ve never seen that before.” At that moment it almost feels that I’m making art because I want to make things that people have never seen before. So I guess the notion of originality is important. But I’m not interested in making something original within an art historical perspective. I don’t want to be part of art history. I don’t want to start a movement.

BC: Why do you make work?

DA: That’s a question I ask myself every day. And my answer is to compensate for my existential discomfort. I mean it sounds corny but unconsciously I’m very uncomfortable with the idea that I’m not here for a reason, that I’m going to die and it’s not going to make any difference. I want to make something beautiful just to have a reason to be here. Also, I want to be loved, not by the world, but by someone.

BC: When you use objects like flowers and birds, do they carry with them a sort of natural romance?

DA: For me, plastic flowers add something almost campy. But also they function like crystals, so they’re about life growing. It’s democracy in a very simplistic way. But it does work like that: flowers grow next to a cadaver and it creates a tension. The pretty aspect of the flower and the gross aspect of the cadaver combine in a way that I like. The birds function in exactly the same way, although the reason I integrated birds into the work is a result of my process. I’d been using a thin jewellery chain to connect all the elements in the sculpture and to circulate the energy. They were a kind of nervous system. But then I was stuck with making a conscious decision about where the chain was going to go to make it look good. It’s annoying when I have to make a purely formal decision, but I always like to have a reason. So I use the birds to carry the chain around. If the chain ended up in the corner, I could just say that the bird decided to take it there. It was a way of shifting responsibility towards the inside of the piece.

BC: So there’s an internal logic that governs the piece?

DA: Absolutely, I invent a logic of materials. That’s what I use instead of making purely formal choices.

BC: Do you work hard?

DA: Obsessively. But I’m not such a hard worker, it’s just that I work all the time. I don’t have any choice.